- Opinion

- 26 Jan 22

Read our full cover story with Glen Hansard, from the Hot Press Annual – originally published in December 2021.

In the two-and-a-half years since he released his latest solo album, This Wild Willing, Glen Hansard has weathered more than his fair share of hard times – including the death of his mother, in the middle of a livelihood-snatching pandemic. Over a cup of tea in a Dublin pub, he talks with remarkable honesty about life, art, loss, family, new projects, class, crises, home, hope – and learning to let go.

As John Lennon noted over half a century ago, “Everybody had a hard year.” Amend that to a hard two years, and it’s a sentiment that feels especially fitting in December 2021. It’s also something that Glen Hansard, despite his hard-fought optimism, knows better than most.

“For a lot of people I know, last January and February in particular were really hard,” he reflects. “I lost my direction. Lost my instinct. I didn’t know what was good or bad. I’d spent my whole life knowing what I liked and what I didn’t like. Then, all of a sudden, I lost all contact with taste. I just didn’t know or trust myself. It felt like a deeply uncreative time for me.”

Between the hopeless winters of lockdown, and the loss of his mother in July 2020, there’s an understandable air of battle-weariness about the Dublin singer-songwriter, as he looks back on the time warp that is Covid-19. But immersed in the warm buzz of Hartigan’s Pub on Leeson Street, he manages to exude a calm positivity too. As an artist who draws considerable influence from nature in its purest forms, it turned out that he didn’t have to look far to reignite his creative spark.

“It was the sun,” he tells me, taking a sip of tea. “When the springtime came, things just seemed to look and seem a little bit better. And of course, we got vaccinated in May, which at least helped us to feel like we could do something.”

Advertisement

Glen Hansard in Kildare. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

POETRY OF LIFE

Since kicking off a life in music at the age of just 14, Glen Hansard has always been, first and foremost, a doer – whether putting in the hard graft as a busker, transcending borders with his Oscar-winning songwriting, collaborating with some of the finest musicians in the world, championing emerging talent, or campaigning on behalf of homeless people in Dublin.

Now, emerging from the stasis of lockdown, he’s at it again, taking on a number of extra-curricular projects, while also busily crafting his fifth solo album, the eagerly awaited follow-up to 2019’s This Wild Willing.

“I’m in the middle of it,” he reveals. “I’m working on it everyday right now, at home. Before that, I was in Italy with my band. We’ve always worked best when we’ve just gone to a house – a place where you’re available to the music all day long.”

As he points out, great music “doesn’t keep appointments” – it just happens when it happens.

Advertisement

“We cook, drink, be in each other’s company and have a laugh,” Glen explains. “And then, when the music feels like it wants to happen, it happens. That could be at two in the morning – or it could be at nine in the morning! We’ve a friend who owns a house out there, and they lent it to us. So we brought out a load of gear, and recorded everything.”

Soundwise, the upcoming album will find him reconnecting with his roots.

“I’m kind of going back to stuff I thought I’d left behind,” he elaborates. “Big electric guitars. It’s actually more in the area of The Frames. I’ve just missed playing with a band so much over the past two years. It’s still raw as hell right now. It’s all one take, straight band stuff. I was touring with a big band for a long while, but now I’ve gone right back to bass, drums, guitar and piano. And I’m loving it. There’s always that classic irony, where the less people you have, the bigger it can sound – because you’re listening to every note, and every note means something.”

Lockdown, he says, hasn’t informed the lyrical content of the album. But the pandemic has certainly brought a shift in priorities, particularly at home.

“In a way, it was good for me to get off the road,” he notes. “I’d been touring flat-out for 15 years. I know for a lot of people it was very hard, and for me it was hard too. But being at home, I was tuning into the family more, and getting into regular habits. Walking the dog. Making the dinner. Making sure there’s wood in the shed. Simple, day-to-day stuff – that is the poetry of life. I was very much in that mode.”

Having lived for a time between a flat in Lucan, New York and the Czech Republic, home is currently an 18th century house in Co. Kildare.

“Marina, my landlady, brought me out and showed me the place,” he remembers. “It was incredible. I said, ‘Look, I think this place is just perfect – but I could never afford it’. She asked me what I was paying in my own place. I told her, and she said, ‘Pay that’.

Advertisement

“I’ve actually had to put my own rent up twice,” he laughs. “I’ve gone to her and said, ‘I should be paying more’. And she’d be like, ‘If you want!’ It’s a beautiful, beautiful house – but it was built in 1720, so it is falling apart. It’s got dry rot, damp and mould. It’s got all the things those old buildings have, but we absolutely adore the place.”

In addition to his girlfriend, poet Maire Saaritsa, the family unit in Leixlip is rounded out by Kes, his two-year-old lurcher. His neighbours, the young brothers Felix and Tom Doran, are also regular fixtures in the home. Relatives of the great Traveller musicians Felix Doran and Johnny Doran, the boys have formed a close bond with Glen – joining him on stage on several occasions.

“They’re great kids, and their parents are amazing,” he says. “Their parents love them, and their brothers and sister love them. But they’re living down in a housing estate near us, and their day-to-day life is just a bit rough, for want of a better way of saying it.

“I thought, if I can give these lads music, and get them interested in music, they’ll never have to work real jobs,” he explains. “Because they’re great musicians. They have it in their blood. All they want to sing is Johnny Cash, Elvis and The Dubliners. They’re not interested in anything else.”

After kitting out his protégés with guitars, and other instruments he had around the house, Glen took them out busking in Dublin.

“I wanted to show them how easy it was, not only to make a living, but to connect with songs,” he smiles. “When we took them out busking, they made like 200 quid in an hour, and brought the money home to their folks. They were blown away. From there, whenever I played a gig, they wanted to get up and sing.”

Advertisement

Glen Hansard in Kildare. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

TIME TO FALL APART

Forging these kinds of enduring connections has long been a defining feature of Glen’s approach to music. But throughout his life, he’s also been forced to contend with the loss of some of those vital connections – and the gaping hole that’s left behind in their wake. He's recently been saluting two dearly departed friends and fellow musicians, Mic Christopher and Interference’s Fergus O’Farrell, in the documentaries Heyday and Breaking Out. But he’s also had to cope with a major loss that was even closer to home.

“It’s a powerful thing, to lose your mother,” Glen reflects. “I’m stating the obvious, but it’s the biggest. That’s the place you came from, literally. That’s your first home, and it’s gone. I’ve had homes knocked down, and it feels very strange. The home I grew up in was knocked down. But when your mom goes, your home is really gone.”

His mother, Catherine, died of a heart attack in a nursing home during Ireland’s first lockdown.

“She was very lonely,” he says. “We spoke to her a lot on FaceTime, but it was really hard for her. I can’t imagine her still alive now, and still being locked down.

“I was in France when I got the news,” Glen continues. “We had just been speaking to her on the phone the night before. And I remember just feeling a huge amount of relief, when I heard. She had emphysema. She smoked her whole life – classic Dub. Dad was a big smoker too, and a big drinker, and he died of lung cancer. They were of that generation.”

Advertisement

With no gigs to offer any form of distraction, and restrictions in force across the country, it was a strange time to be grieving.

“But that was good as well,” Glen points out. “Because everything that happened, you had time to just let it happen. I had time to fall apart, which was really important. I had time to just fall asunder. And then, begin to remember all the goodness and all the beauty of our relationship and our friendship – me and my mom, and our family.”

Despite his close connections to home, Glen feels that her death has had an impact on his already complex relationship with Ireland.

“When my mom died, some line in my connection with this place was cut,” he tells me. “Ireland’s an incredible place. My girlfriend’s Finnish, and she has such a romantic connection with Ireland. And I do too – but because I’m of the place, I also see all of the complexity of it.”

In Ireland, attaining even a slight degree of success complicates that relationship further.

“The weather of opinion – it can be negative and positive,” he reflects. “It’s a funny thing to even say and admit. But when you go out in the street – just heading out to meet someone in town, or whatever – you walk past someone, and you see the eyes connecting. Just a little flash, which most of us don’t even register – there’s a complication in that, which is, ‘Am I being recognised now, or am I not being recognised now?’ It’s fine, but you also have to navigate it. It’s a little bit of Velcro that catches when you’re in a city like Dublin. If I’m in Paris, I just don’t have that.

“If I’m in the right mood, or if I’m in a good mood, it’s all green lights and sunshine. But if I’m in a shit mood, it’s complicated. It’s hard to explain that, without coming off like a dick.”

Advertisement

PASS IT ON

With the release of Heyday: The Mic Christopher Story and Breaking Out, and his involvement in The Mary Janes’ single ‘Heartbreaker’, released to mark the 20th anniversary of Mic’s death, Glen’s also been contemplating the strange position he’s found himself in: “Where I’m the one who will remember these people in my life.”

“They’re gone,” he says, “And I’m the generation who will recall. I remember being with a friend of mine, Dave McGuinness, talking to John Martyn. Asking him, ‘What was Nick Drake like?’ And his response was just really rough. It was just like, ‘I don’t want to fucking talk about dead people. I’m alive – fuck off.’”

As Glen notes, we all tend to “romanticise people in their passing.”

“God bless him, when Mic did his last gig in Dublin, there were like 10 people there,” he resumes. “Now in fairness, there were 10 people there because it was September 11, 2001! But it was hard to see that – hard for Mic. Because Mic really wanted to do well.

“There’s this kind of narrative that’s crept in, that Mic wasn’t interested in success, or that he was somehow above it,” he muses. “I think those narratives are dangerous. But memory is a funny thing. People’s memory of Mic is their memory of Mic – it’s not mine. My memory of Mic is my memory. Same with Ferg.”

Whenever he’s experienced these kinds of losses over the years, it's pure optimism, he says, that's kept him from losing hope.

Advertisement

“I’ve always had this feeling when a good friend dies, that you kind of take on the best of them,” Glen considers. “It’s almost like you inherit the goodness of them. In a way, that’s a gift. Maybe it’s a survival mindset.

“But with Mic, I lost someone that I could just be completely me with,” he continues. “We could fight, and we’d always work it out. Losing that is really hard. One of the greatest gifts in life, if you’re a creative person, is someone to banter with, and someone to have very honest conversations with. Someone who calls you out. We probably are blessed with just a couple of those people in our lifetime. And he was definitely that for me.”

The Frames 1996

Over the years, Glen has taken on the role of champion and mentor for a whole new generation of artists, often giving them a platform at the very outset of their careers. To him, it’s a way of repaying the kindness he was shown as a teenager.

“When I was 15, I was busking on Grafton Street,” he recalls. “My parents had never been on the South side. They’d never know where to find me, if they came looking for me. My mother was a fruit seller on Moore Street. I used to sell fireworks there on Halloween – I was very much of the Moore Street dealer life. That’s why I never busked there, because I’d know everyone. All the women would be going, ‘Ah, there’s Glen! Go on home for your dinner, your ma’s looking for ya!’ Grafton Street, for me, was like going to another country.

“At that time, I met a woman who was 25 years my senior, Philippa Bayliss, and I went and lived with her for two years,” he adds. “She paid for music college for me, and she really encouraged me. In my life, I’ve been very lucky that people have come along and said, ‘I’m going to help you’. I’ve always had this thing of just wanting to pass it on. If someone comes along, and they’re talented – and even if they’re not – just give them a shot.”

Advertisement

As well as directly inspiring plenty of artists on these shores, Glen’s music has also had a profound influence on two siblings in Los Angeles – who’ve gone on to change the face of pop music forever.

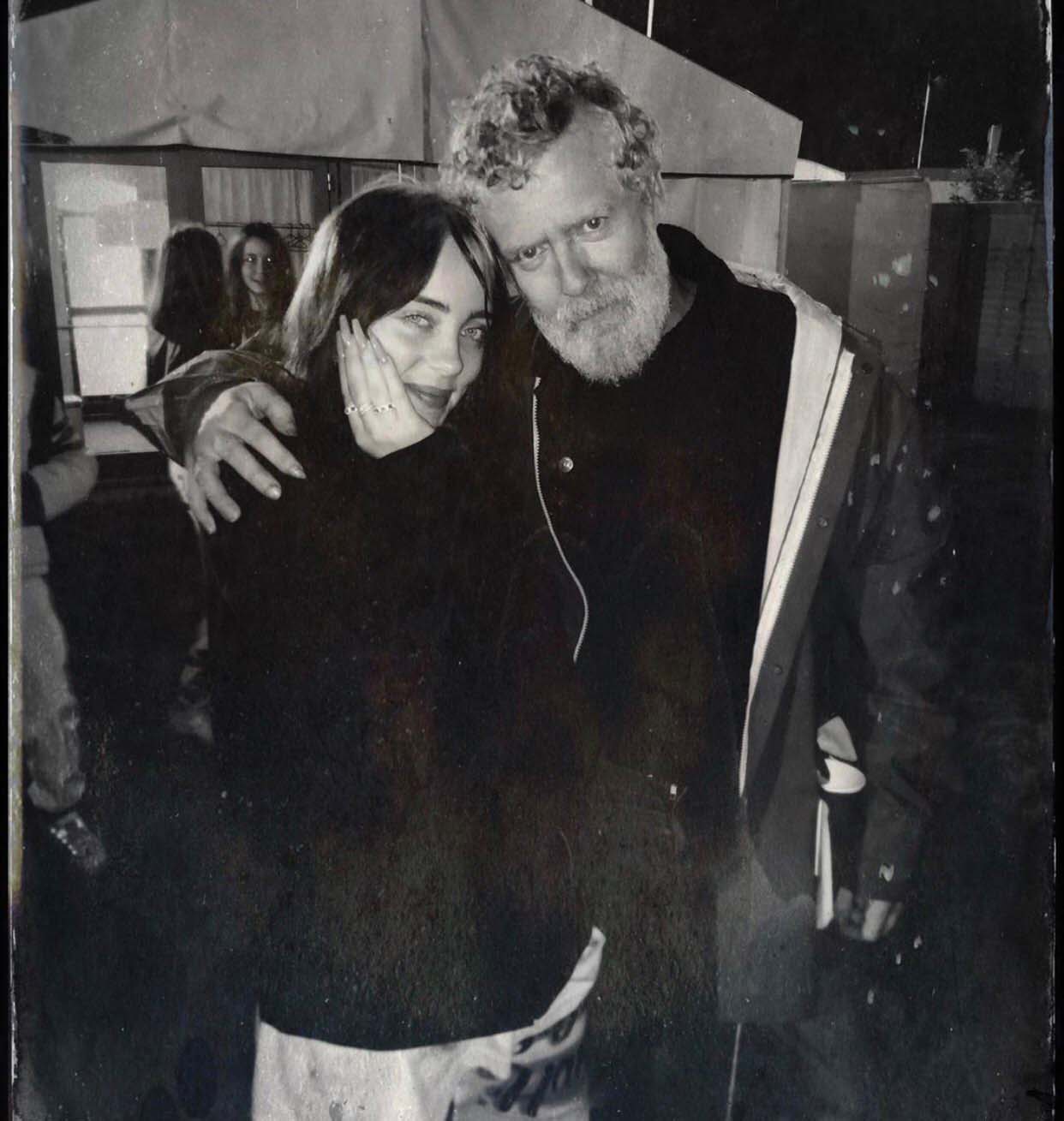

“She was very kind,” Glen says of meeting Billie Eilish at Electric Picnic 2019. “She told me that ‘Say It To Me Now’, a song from way back, was the first song that she fell for – because Finneas was playing the Once soundtrack over and over. The great thing about them is that they’re a family, so they’re super relaxed. And what I love about her is that there’s no bullshit.

“I have to say, I’m not a snob by any stretch – but pop music generally passes me by,” he smiles. “But when I heard her, I was knocked out. It was coming from a dark, introspective place. ‘I wanna end me’ was such a heavy lyric. Me and Maire were listening to her in the car, and then my niece contacted me, going, ‘Fucking Billie Eilish just talked about you!’ It was a great feeling.”

Glen’s annual Christmas Eve busk has also become a space for emerging artists to perform alongside established stars. It's an aspect of the gathering that he especially relishes.

“I remember one year, some guy dropped in,” he recalls. “I had no idea who he was, but he knew the Dylan song ‘You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere’ – because I could see him singing along with me. He had a nice vibe off him, so I said, ‘Go on, you finish it!’ And he sang the last verse. I remember he had a great voice, and great presence. Afterwards, I was asking everyone, ‘Who was the guy in the red hat?’

“A year later, I was in America on tour, and I finally met the guy in the red hat – and it was Dermot Kennedy, who was on tour in America at the time on his own.”

Advertisement

Despite the emergence of countless phenomenal Irish artists in recent years, Glen agrees that Ireland still has a tendency to judge talent or success based on how an act is embraced in the UK or the US.

“We are the worst,” he sighs. “This country lacks so much confidence. The Folk Awards is a bit of a joke. I can predict who’s going to win each year. It’s whoever Geoff Travis likes. Of course he has good taste, and I’m taking nothing from those who win each year, because they’re all great. But there’s no risk. It’s predictable. It’s all pre-ordained by England, and we just follow suit a year later.

“Don’t get me wrong. It’s not that John Francis Flynn is in any way unworthy of the award,” he adds. “He’s very worthy of the award. Same with Lankum. Same with Ye Vagabonds. They’re brilliant. But it just shows little confidence in us.”

DUBLIN’S NOT DYING

While Glen also lent his voice to the campaign to save The Cobblestone pub in Smithfield, he says his position was more “practical” than romantic.

“This ‘Dublin Is Dying’ thing – I don’t buy it,” he states. “Because Dublin’s not dying. It’s changing. Like everywhere is changing. It’s been changing for a long time – becoming homogenised and Americanised. But Dublin’s not dying, because art will always find a way. What made art great in the ‘80s, when my generation were coming into making music, was that there was fuck-all money. There was nothing to do. Now we have everything being developed. Dublin is becoming one big Airbnb.

“I don’t have an opinion for or against that,” he adds, “other than when somewhere like The Cobblestone is threatened by an application to build a hotel. Because the very people who’ll be staying in that hotel will be asking where the good music is. And the receptionist will be like, ‘Well, the place that used to be here!’ It just didn’t make sense.”

Advertisement

In Glen’s life, activism comes from a deeply personal place.

“Homelessness was something that was in my family,” he explains. “A lot of heavy alcoholism and drugs. My cousin was the first AIDS death in Ireland.

“The problem with saying this kind of stuff, is like it’s some fucking credential,” he adds, after a brief pause. “And I hate that. I’m just trying to explain where that instinct, to try and make a difference with activism, came from. It wasn’t me trying to add another aspect to my career. I’ve always been into it, because it’s personal. It was never part of any kind of narrative, but now when I speak about it, it just sounds like I’m trying to sell something.”

Homelessness is now an “epidemic” in Dublin, he argues – particularly for young families.

“I grew up in government housing, in Ballymun,” he resumes. “Every house I lived in with my parents was government housing. Without that, we would’ve been screwed. But successive Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil housing Ministers have utterly failed the working class Irish. And now, the middle class Irish. Artists are being priced out of Dublin. Normal working people are being priced out of Dublin, unless you’re willing to live somewhere with a microwave on top of the toilet. Sinn Féin’s Eoin Ó Broin is the only housing representative that I feel I can actually trust.”

Through his involvement with the Home Sweet Home campaign – during which activists famously occupied Apollo House in Dublin in 2016, to provide accommodation for homeless people – Glen was also exposed to the extraordinary stories of young couples and families living on the streets.

“There’s always going to be people making poor decisions,” he reasons. “There’s always going to be people who fuck up. You’re never going to get rid of that. But the people who are the hardest on these young families are the working class – the people in their own community. Which makes no fucking sense.

Advertisement

“The number we’re doing on each other as a nation is horrendous,” he adds. “We should be standing up for each other. We’ve probably been saying this forever, but it does feel like a basic decency has gone out of us. It’s very easy to look at the Christmas busk cynically – and go, ‘Yeah, you all get together at Christmas because it makes you all feel better about your successful lives’. But I do believe, if people have been good to you, give a little back. If you can, just try to give a little bit of light.”

NO SAY IN MY LEGACY

Of course, with live music making it’s gradual comeback around the world, there’s gigs on the way too. In March 2022, Glen and his Once co-star Markéta Irglová are set to revisit the songs from the film in a special 15th anniversary tour of the US.

“Honestly, it’s just a good reason to see each other,” he says. “We’ve both been so busy, and during Covid nobody saw anybody. We got together three years ago, with Footsbarn Theatre down in Kerry, for Come On Up To The House – this gathering of musicians and actors. Mar jumped over for a gig, and it was brilliant. If Markéta has an idea, she’ll send it to me, and I’ll put a vocal on it. If I have a song, she’ll stick a vocal on it. We’ve always been creative together. So we just decided, why not do a few gigs next year?”

Before that, however, is a US tour with Eddie Vedder. The pair were collaborating on the soundtrack for Sean Penn’s Flag Day in Los Angeles when Covid-19 broke out across the globe – and Glen reveals that they’re currently working together on another, upcoming project. As well as supporting the Pearl Jam frontman for a run of gigs, he’ll also be joining the touring band, “the Earthlings”, alongside Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer Chad Smith, ex-RHCP guitarist Josh Klinghoffer, guitarist Andrew Watt, and Jane’s Addiction bassist Chris Chaney.

“In September, The Frames were meant to play Ohana, this festival in California,” Glen explains. “It ended up just being me – and I ended up sitting in with Eddie’s band. We rehearsed for a week, and it was incredible. Chad Smith is the loudest drummer I’ve ever heard in my life. I’m playing a song called ‘Tender Mercies’, and it’s me on the piano. And then Chad drops in – and I don’t hear anything anymore. We had to iron out a few creases with all of that!”

Advertisement

After those American adventures, Glen will be heading out on tour with his own band, while also finding time to fit in The Frames’ highly anticipated headliner in Royal Hospital Kilmainham in May. “The busier I am, the more things flow,” he notes. “When I’ve got very little going on, I tend to create a stasis.”

While life remains busy on every front for Glen – who turned 50 over lockdown, in April 2020 – he’s also learning to take each day at a time, and, gradually, to let go of control.

“As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realised that I have absolutely no say in my legacy,” he reflects. “None. I can try to steer my ship as best I can. But I’m known as ‘the Once musical guy’. When I meet an average Irish person, they go, ‘Oh, I saw your show’. And I’ll immediately know what that means. I’m glad they saw the show, but people assume that I wrote that musical. Whereas I just wrote the songs.

“So what I’ve realised is that there’s literally no way for me to control that. And it’s actually really freeing. Because now I don’t have to worry about it. I just have to do what I do.”

The Frames play the Royal Hospital Kilmainham, Dublin on May 28. See Glen Hansard's live dates here.