- Music

- 05 Jul 23

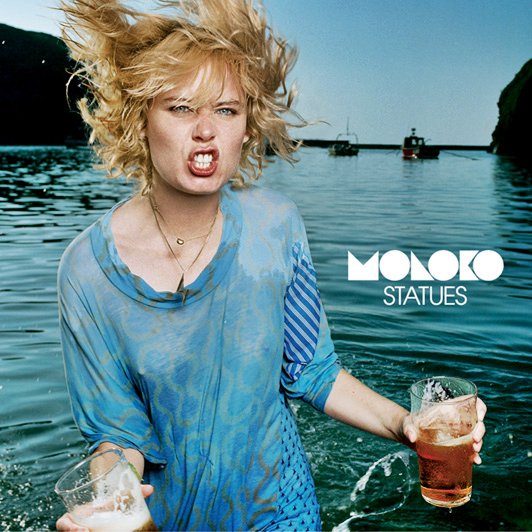

Happy 50th birthday to the iconic Róisín Murphy! To celebrate, we're revisiting a classic interview with the Arklow star – originally published in Hot Press around the release of Moloko's fourth and final studio album, Statues...

Originally published in Hot Press in 2003

Dance is dead, says Róisín Murphy, but if any act is going to raise it from the grave it’s Moloko, proud authors of the over the top and utterly sincere Statues, an album of tremendous pop songs that recapture the glory of classic disco.

You join us midway through a conversation with Róisín Murphy of Moloko, about the death of dance music, the imperishable beauty of disco, and the importance of being earnest.

"The central theme of this record, and what we love about disco in general, really," Róisín is saying of Statues, Moloko’s fourth album, "is how melancholy, sadness, can happen at the same time as euphoria. It’s about tapping into…" She pauses before finishing her remark. "I mean, very sincerely, this sounds really awful, but it taps into this… universal melancholy, this universal sort of… understanding, of the depths… of life." Róisín stops. "I mean, the best disco records, would break your heart," she says, passionately. "You know what I mean?"

Anyone seeking proof of this theorem need look no further than Statues. It’s an old-school disco album, not because its production is anything but modern and forward-looking, but because it’s jammed with tremendous pop songs that happen to be dance classics, in the tradition of song-based disco-anthem bonanzas of the 1970s like Donna Summer’s On The Radio compilation or the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack. Also like classic disco, Statues manages to be both tautly written and utterly, majestically over the top.

Advertisement

On the one hand, quite markedly in contrast to their wonderful but too-clever-by half 2000 album Things To Make And Do, there is literally not a superfluous track, note, beat or breath anywhere on it; on the other, it’s lushly, resplendently arranged for voice, four-square live band, programming, and (!) 53-piece string-and-brass orchestra. Possibly most importantly of all, Statues is arrestingly open; devoid of artifice; full of the thrill of not hiding behind your own intelligence or irony or cool; genuinely moving. It’s, in Róisín's words, "sincere". But we’ll get to that later.

"And," Róisín is continuing passionately, "I think the reason dance music is dead – and it’s dead," she spits, "altogether [silently mouths word] fucked – is the producers’ fault. It isn’t the club runners’ fault, or the industry’s fault, or the marketeers’ fault, it’s the fault of DJs and producers and their egos. It’s because somehow, there’s some kinda gap being jumped, between making clever, beautiful music and just making music to a formula. Producers actually think it’s the same thing now. And I don’t think it is the same thing, at all.

"I think even the most un-musically aware person wants to be emotionally moved, and surprised, on the dancefloor. As a producer, you need to…" She searches for an explanation. "You need to be brave with disco music, if you want to keep disco alive.

"I was standing on the dancefloor in Ibiza this summer," Róisín reflects. "And I was just going [cocks head as if listening] Okay, there’s the build. There’s the drop. There’s the vocal breakdown. I know exactly what piece of the vocal they’re gonna loop there. And…" She shakes her head. "I know I work in music, and so on. But I think it’s gotten so bad that even the most Joe-Bloggs, so-called ‘musically uneducated’ person, subconsciously knows what’s gonna happen on every single dance record.

"And, it’s the same music you hear in the disco as you do in a gym?" she continues, with quiet incredulousness. "I mean, that’s just not right. That’s wrong. Dancing itself, is sacred. To start off. It’s a sacred thing. People don’t take it seriously enough at all, I don’t think." She scowls, utterly seriously, as if beholding the aftermath of a desecration. "Going on the dancefloor with no respect whatsoever. Sploshing bloody beer all over each other, and just… being aggressive, with something that is so special, and uplifting and important.

"The whole kinda dance music culture that I know of," she says, "in England, comes from what I grew up with [in Manchester and later, Sheffield], which was northern soul. Which was about ordinary people, with ordinary jobs – and probably in most cases jobs that they hated, lives that don’t really fulfil them – needing to go out, and dance once a week, all night long. And knowing every word of these plaintive soul records, that are all about pain, and despair, and love. Dancin, dancin, dancin, ‘til they’re uplifted, away from the bloody.. treadmill in the gym. You know?"

If any band can "save" dance music, can still manage to provide dancefloor transcendence in cynical old 2003, it’s probably a strange, wilful, hyperintelligent, overemotional lot like this. Lumped in with then-emerging trip hop in their early years, constantly referred to as ‘experimental’ (that catch-all word for uncategorisable artists), Moloko have made a career of sliding gleefully between and among musical genres, trawling for inspiration as they go. A headache for marketing departments and a treat and bonus for everyone else, their love and mastery of P-funk means Bootsy Collins is a fan; their history of mixing blues-rock drumming with house and dub and European electropop and whatever you’re having means they’ve won the hearts of the alternative-nation intelligentsia; and their two crossover singles (‘Sing It Back’, 1999 and ‘The Time Is Now’, 2000) ensured that the mainstream, at very least, knows who they are.

Advertisement

And of course they are passionate participators in dance culture. Mark Brydon, Róisín's other half (in Moloko and in life), was a record producer when the two first met in Sheffield in the early ‘90s; ‘Sing It Back’ was all but born in Ibiza, after producer Boris Dlugosch remixed it into the version that made it onto 110 dance compilations by the end of 2000, when they stopped counting; and Moloko’s last two projects, post-Things To Make And Do, were the remixes-and-rarities compilation All Back To The Mine and a second collaboration between Róisín and producer Dlugosch, this time resulting in the dance-pop floorfiller ‘Never Enough’.

Last but sweetest, ‘Sing It Back’ was actually written by Róisín in homage to a Manhattan club she loved called Body & Soul, during a spell living in New York. To speak with Irish-born Róisín though (she moved from Arklow to Manchester at 12) is to realise her first allegiance is not to "dance" the genre or scene, but to music in general, and to dancing itself. In any case, Róisín is not losing sleep wondering what people make of her band anymore.

"Whatever happens, whomever supports this record or doesn’t, whatever props we get or not, I think eventually, within a year, it’ll be a big album," she says. "Because I just feel, intuitively, that it’ll grow, and grow, through word of mouth, and that people will love this record. Cos it’s very sincere.

"I think it is our most concise record," she says, pride radiating as she speaks. "It’s our most perfectly formed album. There’s very little fluff, or frill, to it. It’s just ten songs. And we’re really interested in songs at the moment. And it’s very direct emotionally, I think. It’s the most direct record we’ve ever made."

The massive response, on dancefloors and off, to Moloko’s two most "normal" tracks –their two beautiful, string-and-voice-and-melody driven "proper songs", both with spectacularly romantic, fatalistic wordplay and the mood of driving, traintrack inevitability that all world-calibre disco-pop classics have – was what made them reassess the value of relatively straight songwriting.

"When we toured the last album, we saw the reactions to ‘Sing It Back’ and ‘The Time Is Now’," Róisín remembers, smiling. "And we did want more of that, to be able to go play shows that would have that intensity from start to finish. So to a certain extent we wrote an album with that in mind. But also," she considers, "as you get older, you get more confident about expressing yourself, about saying what comes naturally to you. And maybe that comes at the expense of a certain amount of playfulness. But what you gain is a sort of directness, and a sincerity.

Advertisement

"That’s not to say this wasn’t an experimental record for us to make," she clarifies, a bit proudly. "Because actually it was the most experimental thing we could do."

Not half. Experimental not only in the very real sense of Moloko recording and producing the whole record in-house and Mark Brydon and keyboardist Eddie Stevens scoring strings and brass for 53, but in the way of Róisín reenvisioned her own role as singer and lyricist.

"I think I‘m more of a lead singer now," Róisín reflects. "We were much more playful, experimental, when we started. And I was lower in the mix as well. And back then, I was more interested in the idea of songs as puzzles, rather than as sort of… personal… y’know, based on what’s going through my mind.

"On this record, there are some rhythm patterns and kinds of melodies that I’ve never found before, like on ‘Over + Over’, where I go: ‘Since that day I wake up early/ Every morning, which is good…’ Which is much more a speech-pattern kind of melody. And that was shocking for me, when I heard myself back, singing that kind of melody."

When I ask whether singing such extraordinarily emotionally direct music is something she’s at all nervous about, Róisín goggles at me with a kind of slightly pained expression, as if I’ve just asked whether she "likes" someone that, as it turns out, she loves.

"I…" she begins, searching for an expression big enough, "am gagging to perform this record. It’s so meaty emotionally, there’s so much drama in it, that it’s going to be a joy to do live."

Appositely for such soul-baring music, the video for ‘Familiar Feeling’ – the album’s massive, pounding leader single, a beautiful amplification of the dusky, ecstatic fatalism conjured on ‘The Time Is Now’ – has been given a truly remarkable promo video, which takes place on the dancefloor of one of Róisín's beloved northern soul all-nighters. It features the scene’s own regulars as extras (they’re smashing dancers to a man, incidentally). As well, the actors – not least Paddy Considine, of A Room For Romeo Brass – have managed to conjure several moments of astonishing intimacy the likes of which this viewer has not seen in a film for many years, never mind a music video.

Advertisement

"Well, Elaine [Constantine, who made the video and also photographed Moloko for the album sleeve], is my friend, but is also one of my favourite image-makers around at the moment," agrees Róisín. "’Cos she makes images with so much lifeforce in them, and so much energy in them – and so much sincerity – that they’re actually quite shocking. Even though they’re not sort of trying to be shocking.

"In a way, the record is like that. It’s not trying to be shocking. But the sincerity is shocking. Being sincere, in today’s day and age, is the most shocking thing you can do."

"We just wanted to fight": The dark, violent, snoggy story of Ant Turquoise Car Crash The, Róisín Murphy’s great lost teenage band:

"I was in a band when I was fourteen. We were called Ant Turquoise Car Crash The, and we played two gigs, and all we did was fight onstage, and make noise, and there were no songs at all.

"I used to hang around with all these boys who wore black. I didn’t hang around with girls at all. I was really burnt at school by girls. And I had years in my adolescence when I didn’t know any girls at all. So none of these boys were my boyfriend, but we were all totally obsessed with music. You know. It started with Jesus & Mary Chain, and then went to Sonic Youth, Butthole Surfers, Dinosaur Jr, all the Sub Pop stuff, Spacemen 3, things like that. And then later on – ’cos we were in Manchester – we got into the Manchester scene, and from that into dance music.

Advertisement

"But we were talking about Ant Turquoise Car Crash The the other day, and somebody said, 'Oh, God, that sounds a really pretentious name.' And my friend who was around at the time said, ‘Actually, no, they were the most unpretentious band, ever. Because most bands have the pretence of wanting to make songs.’ (laughs hugely) And we didn’t want any of that. We just wanted to have a fight. We used to kind of go to rehearsals, and turn the lights off, and make loads of noise in the dark, and then I’d snog one of them.

"It was great. Only lasted two gigs, though. (Thinks) We were great at marketeering, though. One hundred and fifty people came to our first ever show, purely from word of mouth."

Read our live report of Róisín Murphy's stellar show at Trinity College on Sunday here.