- Music

- 22 Sep 20

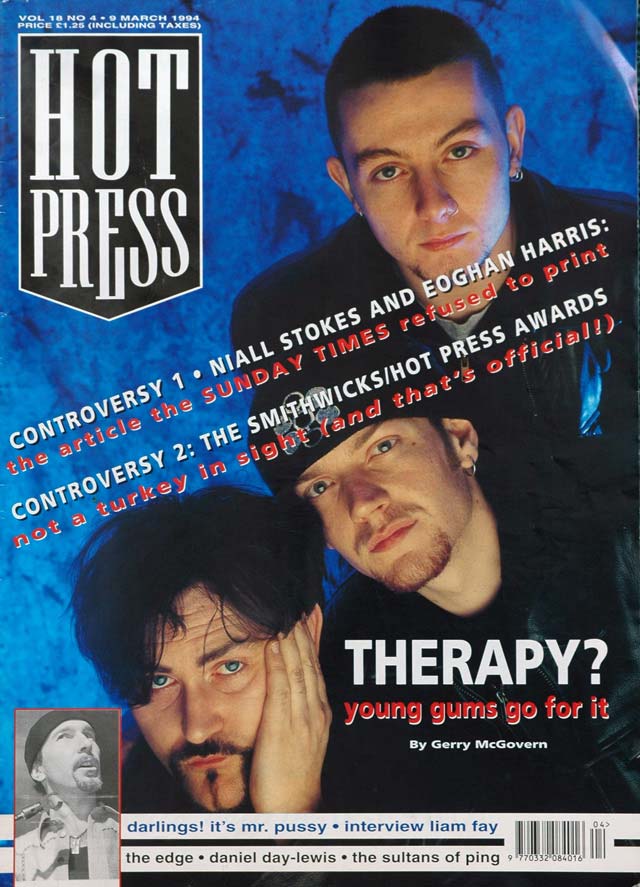

To celebrate his 55th birthday, we're revisiting a classic interview with Therapy?'s Andy Cairns – originally published as a Hot Press cover story in 1994.

Few Irish albums have been as eagerly awaited as THERAPY?’s Troublegum and while the jury has yet to deliver its final verdict, early indications suggest that the band from Larne may be about to fulfil their own prophecy and become multifuckingnationally huge. But does taking on the world mean having to compromise the hardcore principles they’ve fought so hard to protect? ANDY CAIRNS and MICHAEL McKEEGAN tell Hot Press trouble-shooter GERRY McGOVERN that displaying your gums doesn’t mean having to sacrifice your teeth.

* * * * * *

I saw Therapy? play their first real gig in Dublin a good few years back. They were supporting Whipping Boy in the by now sadly missed Underground Bar on Dame Street. No, I didn’t think they’d be as big as they’ve become. I remember the gig for that great line from ‘Potato Junkie’: “James Joyce is fucking my sister.”

Therapy? have a knack for netting the nugget, whether it be a lyric or melody. Their new album, Troublegum, is full of punchy riffs and melodies, and memorable punch-line choruses. Because despite their ‘difficult’ Captain Beefheart-inspired roots, Therapy? have become a rocking, good-time populist outfit.

Advertisement

Watching Therapy? play at Cork City Hall was to see a rock ’n’ roll animal at play. This was a giant beast, with a thousand heads and many more arms and legs. And when the riff drove in, the commands were simple: rock to the beat, push to the limits, headbang your worries away, sweat like a pig, fuck growing up, and let’s have a good time, ‘cause it’s only rock ’n’ roll.

There are boxes waiting for all of us, and labels waiting or already attached to all our favourite groups. And these labels are meant to stick because those who make them very often invest personal kudos in being associated with such-and-such a labelled item.

Some years back Therapy? were labelled as indie darlings. They had two independent No. 1 EP’s under their belts and a reputation for being alternative and industrial, with punk and dance attitude. Their debut album, Nurse, was a mix of all the above. Listening to it, I got the impression that Therapy? weren’t exactly sure what they wanted to be, that they were experimenting, trying to find their musical feet and a definite direction. Whereas, listening to Troublegum, it was obvious that a direction had been found; every song sounded like it had come from a unified concept.

“I think Nurse was like, as you say, experimenting and finding our feet,” singer and guitarist Andy Cairns reflected. “In the evolution of Therapy? every record has changed slightly. I think really with Troublegum we wanted to make a very focused, a very between-the eyes sort of album, sonically and also lyrically. Nurse was like . . . we thought too much about the music, rather than get on with it and let it go very natural. We would sit three or four days and labour over it, trying to get some kind of sound. Whereas I wrote the songs for Troublegum on acoustic guitar. So, we let it occur more naturally, rather than trying to make it sound weirder than it should sound.”

“On Nurse, the energy was pulling in too many different ways,” bassist Michael McKeegan suggests. “Whereas with Troublegum we’ve managed to get it coherent, and it all sounds consistent. Every song sounds like it’s from the same album.”

On the face of it, Troublegum is very much a rock/pop album. However, lyrically there is a sense of foreboding, despair, and of being lost and confused. Was the juxtaposition of the sweet riffs and melodies and sour lyrics a deliberate decision. “We’ve always worked with juxtaposition,” Andy explains. “Even from the time of Pleasure Death and things like that. It’s like if you have two sorts of things fighting with each other all the time, it keeps it vibrant and alive.”

For Michael, the use of juxtaposition was essential. “I think with a lot of bands they’ve got really aggressive, heavy music and then they make everything like just to one extreme. Whereas we didn’t go out to make a grunting, no melody, big noise album. Yet again we didn’t make it lush strings and piano ballads with the melodies either.”

Advertisement

Listening to the lyrics, you could be excused for thinking that Andy lives a miserable, fucked-up life. However, as is so often the case, singing about despair is a release in itself.

“I use anger and despair as an energy,” he points out. “If you rebel against it by shouting and making enough noise you can hold your head up with some sort of dignity.”

One of the major differences between Nurse and Troublegum – and there are many – is that the vocals are well mixed and can actually be heard quite distinctly. Have the lyrics become more important for Therapy? “We got the music done really quickly, and then spent the most time we’ve ever done on a record on the vocals,” Andy states. “Because there’s lots of moods and personal twists in it, so we just sat down and made sure that the delivery was spot on, and most importantly, honest. Part of it is probably because we’ve got better melodies and lyrics. Part of it is also that before we weren’t so confident as singers on Nurse, so we tended to use the voice as a way of expression and painting pictures, sort of as an instrument.”

Religion rears its ugly head on nearly all the songs on Troublegum. And it is indeed an ugly, suffocating, soul-eating head. In many ways you could be forgiven for thinking that some sort of musical exorcism is taking place. (Although that is only when you stop humming and start listening.) Were the religious-smeared songs a process of exorcism?

“The whole record was like an exorcism for me,” Andy comments. “It took me two months going through all the shit that had happened in my life. A lot of it was painful to think about. I wanted to make it powerful.

“When I was young – I came from a Protestant background, you know – we were sent to Sunday school. You know, those Presbyterian-type preachers, they make a really big high theatre. So, it’s all like, ‘Ye will burn in hell! And ye will rot!’ When you’re seven years old, getting these graphic descriptions, these horrible atrocities . . . For years I was tortured, absolutely tortured by these. If I did anything wrong I was scared to die.

“In America, we were on a long tour, and it was very hot. And the heat affected me, I think too. And I began to think about a lot of things. Sometimes I just thought I was going insane, just thinking about these things. And the only way I could get it out of my system was to write and to write and write and write. And when I came back from America I had just pages and pages of this stuff.”

Advertisement

I got the impression, that if indeed it was an exorcism, it was an incomplete one. That the demons may have been faced but they had not been mastered. That a religion which had so dominated his life, still had its unique pull. “No, no, I’m still not sure about religion,” he agrees. “It’s not like I’ve decided there is no God and I walk about feeling happy and relieved. It’s not like that. I still don’t know. Everybody at the end of the day thinks about life an awful lot, I’m sure. Whereas it’d be great to think like when you’re dead, you’re dead and in the ground, but I can’t accept that. I don’t know whether it’s because I’m from Ireland that the spiritual thing is in the background.”

Ireland + religion = bloodshed if you live in the North and repression if you live down South. Why was it, I asked Andy, that something which is supposed to heal the spirit, has so often been used to kill the body?

“Religion is meant to be used as a form of faith and a form of devotion, but an awful lot of the time it’s the absolute fear that people have of going to hell, or fear of being lost and abandoned, that keeps them turning to religion. That dread fear is something that drags an awful lot of good people – not even good people – an awful lot of abused people to turn to it. I’ve known friends that really got caught up in religion. You really do believe so strongly that you can get really caught up in it.”

Was rock ’n’ roll an opportunity for Therapy? to escape from the whole suffocating mess, the fast car out of town?

“That’s true,” Andy replies passionately. “People ask us an awful lot of the time overseas, why don’t we sing about Northern Ireland? Rock ’n’ roll is one thing up North that does unite a lot of kids. It’s like you go to see a band play at Ulster Hall. Both sides of the community are there, getting along and enjoying themselves. Whenever you’re surrounded twenty-four hours a day with killings and slaughter and ridiculous politics, the last thing you want to hear when you go to a rock concert is somebody up on stage preaching.

“A teenager in Northern Ireland has the problem of growing up, discovering his sexuality, finding out about girls, finding out what he wants to do with his life. All this, before you can take into account that you’ve been brought up in a dodgy area, a deprived area, where there’s terrorist breeding grounds, drug dealer breeding grounds. That’s sort of a double-barrelled sort of attack.”

Still, rock ’n’ roll can only bring you so far. That is, of course, unless you want to live with a totally new identity, in a new land, a new home. For most, you may often curse your past but leaving it behind entirely is a different matter. Therapy? have taken the fast car out, but they take it back too. They’re still very much a part of where they came from. But where exactly are they from? Because identity is a complex and confusing web for those who live on this island. I asked Andy what identity he considered he had.

Advertisement

“Whenever I go to England I feel Irish, very much so. When I go down to Ireland I feel very much British.”

“If people hear you’re from Northern Ireland, they either think you’re British or Irish,” Michael elaborates. “You either support the IRA or the UVF. And it’s not like that. It’s just like such a huge complex problem. Like I would never pretend to fully understand it. And there’s so many different viewpoints.”

But if they were asked to say what nationality they were, what would they say?

“We’re a Northern Irish band,” Andy comments. “If ever I’m asked my nationality in a hotel or wherever, I always write down ‘Northern Irish.’ Because I don’t feel Irish. I feel like a foreigner when in Southern Ireland, but I feel like a foreigner when I’m in England.”

We down South suffer from identity problems too. This former colony is still viewed without the ‘former’ by many British people. And it’s amazing how the more successful we become, the more British we become in the British mind. (“Britain will soon have to wake up to the fact that The Cranberries, with their softly insinuating musical cries, are a rather precious export . . .” NME – 29th January 1994.) I asked Therapy? whether they had noticed that irritating post-imperialist habit the British have of labelling successful Irish people, ‘British’.

“Oh yeah, oh yeah, especially when they’re successful,” Andy agrees. “Like in soccer its always been like that. When the Northern Irish team is defeated they say ‘Aw, that’s a terrible defeat for the Irish.’ But if we win 4:0, it’s like “And what a great victory for the British team.” Michael can’t help but laugh. “That’s very true. That’s very true.”

Whatever the differences between Northerners and Southerners, it can still be said that we share one essential thing in common: humour. Or perhaps sarcasm, the art of the put-down and the savage wit, would be more accurate descriptions. Such delicate skills go back a long way, it would seem. In 1775 Samuel Johnson was quoted as saying: “The Irish are a fair people – they never speak well of one another.” Andy and Michael laugh knowingly. Do they encounter many of the ‘who the fuck do they think they are’ characters when they go back home.

Advertisement

“I think that there’s a lot of people very proud of us,” Andy replies. “But then for every person who’ll say to you, ‘well done’, there’s going to be somebody who’ll say, ‘who do you think you are?’ We noticed it particularly at the start in Belfast, which we thought was really funny. We’ve still got a lot of friends there, and we’re obviously selling more records in Ireland, and more people like us.”

Still, having your feet placed firmly on the ground – after perhaps having had a fist placed firmly in your mouth – is not as bad as it might seem to your dentist. Better to have a Shane MacGowan grin than an LA smile?.

“Oh no, I hate that,” Andy states firmly. “I’m glad it is the way it is. Because what a lot of Northern Irish people have got is a very resilient nature, which I think the Troubles have probably contributed to. People’s sense of humour tends to be more scathing. Opinions are more direct. And it’s no bad thing really. If you weren’t from Belfast and were surrounded by yes-men all the time, telling you how wonderful you are, it would be hard to keep your feet on the ground.”

“Give peace a chance,” John Lennon once sang. Well that was easy for him to say, living in the luxury of marijuana-land. However, peace – that incredibly abused and sullied word – looks like it just might have a chance in Northern Ireland this time. I asked Andy and Michael if they, on their visits home, had encountered a change of mood, a softening of attitude.

“I think there’s a definite shift,” Andy reflects. “But the only thing is that it needs time and it needs a process of re-education, and people trying to get on. The worst thing is that people from outside think it’s as simple as two people signing a piece of paper and then going and burying their armallites in the back garden. A lot of people don’t seem to understand that there’s so much money involved. There’s drug rackets and things like this. A lot of people will lose their livelihood if this war stops.”

Until peace does come, rock ’n’ roll will still offer many young people a way out. Have Therapy? perhaps taken Route 66 too literally, and musically, in any case, driven too far into the heart of rock ’n’ roll – America.

“Yeah,” he agrees. “I think that that was a very naive thing for us. It was never a conscious thing. It’s as simple as this; all my favourite bands are American. But I don’t think, hopefully, that we’re selling ourselves too much to America. I think we’ll always have a certain sense of humour which will reflect our culture. But at the end of the day, the stuff I listened to as I was growing up was American rock, especially the punk and the hardcore scene. And that’s probably influenced the way we play and the way we sing.

Advertisement

As Michael says, when you’re growing up nowhere – whether it be the epicentre of the arsehole or not – you want to go somewhere.

“Where I’m from it’s very quiet,” he explains. “And you’re not going to go down the road to see the local pub band. You want to see American teenagers in a movie. You want to listen to exciting music.”

There are those who still believe that England invented rock ’n’ roll, and that even if it didn’t that The Beatles and Rolling Stones perfected it, and that since then it has remained a quintessentially English thing. These English romantics have always attempted to create the myth of a world-dominating British scene. In 1994, like 1993 and before, this scene simply doesn’t exist. But that hasn’t stopped these desperate inventors, and Andy and Michael agree that there is a sense of desperation behind the incredible hyping of a group like Suede.

“I had a conversation with several people out of those sort of bands at the Brats Awards – the NME thing – last weekend,” says Andy. A lot of those bands like Blur, Suede… They’re all great people. But it seems to me that the British desperately want another Rolling Stones or Beatles so badly. Desperately, desperately, desperately. And you can’t fabricate that kind of attitude. That was just a natural thing that happened. You can’t try and make it happen again.”

I think in the UK the music press is so dominant, people are so conscious of, ‘will I be liked?’ and ‘is it right?’” explains Michael. “A lot of young bands start worrying about where they should fit in in the grand scheme of things. And to me a lot of the best bands are the ones who blunder into things, stumble onto a sound and just do what they do naturally.”

It’s a long way from Captain Beefheart to Beavis and Butthead. It’s a long way from indie darlings to metal maniacs. Before the Cork gig, the high-pitched vocals and speed guitars coming through the PA said one thing: heavy metal, man. And the preponderance of Metallica, Megadeth, Slayer, Deicide, Guns ’n’ Roses and Faith No More t-shirts reinforced that point. (There were other mixtures too: Pearl Jam, Red Hot Chilli Peppers, Bad Religion – even Suede!) There were, of course, lots of Therapy? T-shirted young lads waiting about for the gig to begin too. I noticed a group of about five or six of them gathered in a circle, head banging away to their hearts content, playing air guitar with their hair.

“I don’t really care who comes to the gigs,” admits Andy, when asked why Therapy? were now attracting such a substantial number of metal fans. “I’m flattered that anyone likes the music. I think if you start being arrogant about what your audience looks like, then it’s getting into fascistic terms, where you’re dictating the aesthetics of the crowd. Some people in the Beavis and Butthead mode tend to like our music. But I don’t mind. ‘Cause they’re still kids coming to concerts. But I’ve no problem with it.

Advertisement

“We’re not trying to cross over into the metal market or anything, but there seems to be something in our music which attracts heavy metal fans. We’re certainly not pandering to them in any way. If they’re having a good time, that’s all part of the show.”

I hear the indie fanatics shriek ‘sell out’. Which is alright, because such indie heads are usually full of pretentious, elitist shite. However, having said that, there is no doubt that Therapy?’s music has made a substantial shift from its more hardcore roots.

“We’ve always really liked the sort of music we play now,” Andy explains. “But it’s just that we weren’t particularly good songwriters. We used to sort of spend a long time thinking about things too much. And it was very raw. All that experimentalism in the early days, and a lot of the chaos in the guitars was because of the way they were recorded and because we were younger and everything.

“We’ve just developed naturally to where we are now. It’s not like we’ve become The Eagles or anything like that. No, we didn’t deliberately change it. It’s just that we wanted to sort of focus the songs more. Like on Troublegum, where it’s hitting you between the eyes and rushing out of the speakers. We wanted to hone the songs down so they did that. Basically, get rid of a lot of the baggage which was on the earlier stuff.”

The ‘indie cred’ debate is a sore point with Therapy? Not that they have sleepless nights over it, merely that they believe that much in the indie world stinks of a sickening hypocrisy. “You can’t go on forever desperately trying to cling to your indie roots,” Andy explains. “We’re selling more records now. We have to take that in our stride. And if you’re worried about what the NME’s going to think of you, then you’re not going to last very long as a band. Because the most important thing about a band should be what a band think of themselves, and if a band still respect themselves, and if they still feel good playing the music.

“At the minute this is the happiest we’ve been. We have a brilliant album and we’re really proud of it. And we really enjoy playing the songs and we just have a great time live.”

Michael finds the whole indie scene hard to stomach “I think that too many bands are worried about this indie cred thing. It’s really annoying. Because loads of them have gone the same route as we have. But we always seem to catch the flack for it, whereas they’re alright, and it’s kind of annoying. We never said that we would never sign to a major label. We never said that we were this great underground band like Slint, that would split up after two great albums. We just did things and they happened. And everyone said these things on our behalf in the press. And then they built it up. And then all of a sudden you sign to a major and you get the boot.

Advertisement

“At least we were honest about it. Like, the number of indie bands that are on indie labels in the UK, that are all signed to majors for the rest of the world – it’s a bit sickening. At least we were honest about it, and signed to A&M worldwide. OK, we’re on a major label. We’re not going to try and hide it behind some little front. Like, these bands are so concerned about keeping their cool, just for England, just for this tiny, small island, with all the press attention there. It seems to be the cred thing to be indie and alternative and all that. Whereas so many indie labels are funded by American majors.”

I know I’ve used this quote many times before but I’m going to use it again because I think it defines the very essence of what rock ’n’ roll is. It’s by Mr Rock ’n’ Roll himself, Chuck Berry: “Hail, hail rock ’n’ roll/Deliver us from the days of old.” And that’s it, isn’t it? Rock ’n’ roll is a form of deliverance. For three working class lads from Larne it has opened up the world and a future. In a time when so many working class people don’t work, Therapy? are working at something they love.

“I think because of the background we come from, and particularly because it’s a Northern Irish working class background, we’re just very grateful for what we have,” states Andy. “You know, every day I wake up I can’t believe how lucky I am. But we’re not scared about success. We’re not going to turn round and go, ‘oh my God, this success is so terrible.’ We know that we’re very lucky, and that there’s an awful lot of people out there who would give their right arm and leg to be doing what we’re doing. And it would be very, very pretentious of us to turn around and say we’re having a miserable time. We’re having a great time.”

As I left Cork City Hall after the gig I noticed a young lad lying with his back to a railing. His t-shirt was soaked with sweat and his face was tugged between joy and exhaustion. He looked at me for a moment, raising his eyebrows, as if to say, ‘that was something, wasn’t it?’ Later that night he probably dreamed of starting up a rock ’n’ roll band.

Revisit Bill Graham's original 1994 review of Troublegum here.