- Music

- 10 May 22

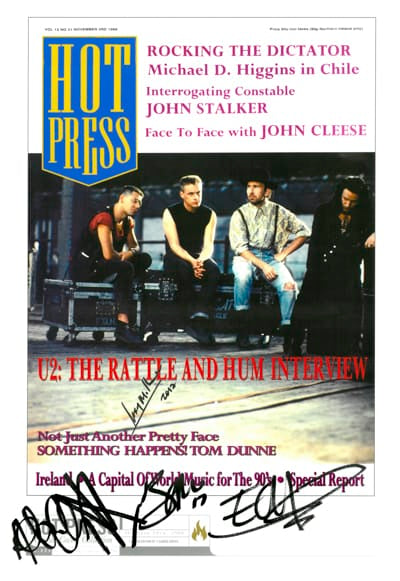

To celebrate the U2 frontman's 62nd birthday, we're revisiting his classic interview with Liam Mackey – originally published in Hot Press in 1988...

Through the office walls comes the rattle and hum of typewriters and tape-machines as stout-hearted volunteers attempt to wrestle the contents of four hours' worth of cassette recording onto paper. Ah yes, I do believe we've been down this road before. I seem to recognise the territory. "I'll always have plenty of time for Bono but rarely enough tape." I'm not much given to quoting myself (I leave that to others, har har), but that line which I wrote after interviewing U2 three years cars ago, applies as forcefully on this mad Monday deadline afternoon, that follows another long, late-night conversation with yer man.

"An awkward sonuvabitch", is how he, not unhappily, describes Rattle And Hum at one point, and so, at least in its preservation of that spirit, you might get away with describing the fruits of last night's labours as The Interview Of The Album (of the film of the book of the band of the controversy... of which more later). Then again you might not.

The world of journalism loves the concept of 'the definitive interview' - along with The Great Scoop, it's a kind of Holy Grail of the profession. But you can forget about even getting close to the glittering prize as far as encounters with Bono are concerned, not least because here is a man who readily admits that he can scarcely define himself to any satisfactory degree. Which, of course, only serves to render even more glaring the supreme irony of his being perceived as rock's Man With The Answers.

Nope, what we have here is not a man whose personality can be so very easily gift-wrapped, tied and placed quietly under the tree – Joshua or otherwise – more a jack forever popping out of whatever box people reckon they have him in. So no Definitive Statement, but between the public role and the private man, between the urge to get a lot off his chest and a guardedness that comes from knowing how print makes permanent and headlines distort, there's a lot of talk and thought and copious amounts of coffee, as 1988 unwinds and the first decade of U2 slips away.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, outside in the distance, a wild-cat did growl – but it's cool. It's only Niall, patiently asking, if there's any chance we might have this thing in print, by, say, the onset of Summertime. So, as the production staff plunge headlong deeper into the maelstrom, let's go back to the midnight hour in a quiet room by the sea...

We begin on a sobering note with Bono describing how he came to write a song for, and then meet, the late Roy Orbison, who'd died just the day before the interview was originally scheduled.

"The song that stood out for me on the soundtrack of Blue Velvet - which was a film I really liked - was Roy Orbison's 'In Dreams'. One night when I couldn't sleep in London, just before we played Wembley Arena, I stayed up listening to this tape. Y'know the way you can put a tape in, and it just keeps going 'round and 'round, and you come in and out of consciousness – well, I always seemed to wake up on that song, 'In Dreams'. And I thought it was the most extraordinary song 'cos it breaks all the rules of pop music. And then there was that extraordinary baroque voice.

"So next day I woke up and I started on this song, 'She's A Mystery To Me'. I became a bore and talked about Roy Orbison all day. I played the song – or what I'd started of the song – to the others in the band and they liked that. Or maybe they liked the fact that it stopped me talking about Roy Orbison (laughs). I was just going on and on about him. Anyway, after the concert in Wembley Arena, I came back and I was sitting down in the dressing-room, working on this song and basically trying to order everybody into buying every Roy Orbison record ever made, when there was a knock on the door.

"It was our security man, John, and he says, 'Listen, I've got Roy Orbison outside could he come in?' And everybody just looked at me and I said, 'Look, I didn't know he was at the show'. Nobody had told us he was coming. So there was much laughter and abuse...

"And he walked in and he just said (quiet American accent) 'I'm an instinctive kinda guy and I can't tell ya why I loved the show but I loved the show'. Then we got talking about songs and he asked for one, so I just took out the guitar and I played him 'She's A Mystery To Me'.

Advertisement

"Later, when I was in Los Angeles, I met him a few times and we started off a few things together. And his family opened up to me, were very good to me. I found him to be a very wise man, he had a lot to say. He seemed to be a man who was incredibly surprised at his own talent. I mean, he had the voice of an angel – and, well, now he is one."

Looking back on U2's '88, Bono pronounces himself "surprised and shocked" that Rattle And Hum – an album he describes as "a wonderful mess of looking forward to the future, bits from the past and bits from the present" – should sell as well as it did.

"I don't understand how we sold five million double albums – I can't figure that out," he says. "I mean we do our best to shake off the not-really U2 fans and, we thought, if anything is going to shake 'em off, it's going to be this, 'cos we've essentially stripped the band of its sound."

The record certainly shook off some of their long-time critical support, as evidenced by an unprecedented amount of negative press, especially in America. "I always expected criticism," says Bono, "and in a way we were excited by the fact that people either loved or hated the album. We were getting reviews that said it was the greatest live LP in the history of pop music and reviews that said it was dog-shit. And I was thinking that it's been a long time since a record in rock'n'roll had that kind of impact – people just don't care enough about rock'n'roll usually to talk about it in such a heated way. So I must say we were flattered by the love-hate reaction to the LP. But what I was disappointed in – in both the praise and the criticism – was the lack of insight into the LP, lyrically, in what it said about us, U2. There's so much in there, so many heavy things – it has a beginning, middle and end in its own ragged way. And that people didn't question the idea of why we did 'Helter Skelter' other than 'why are they doing a Beatles' song?' – that people didn't think further than that, I must say... amused me."

One of the central criticisms was that by invoking, in both image and song, such legendary figures as Billie Holliday, Presley, Lennon and Hendrix, U2 were engaged in a form of self-aggrandisement by association – a hi-jacking, for personal benefit, of the great rock'n'roll tradition.

"That was maddening because the intention was the exact opposite," Bono asserts. "I mean rock'n'roll is a great tradition, and we are part of it - and maybe you'll think this is funny -but we thought it was, kind of, the most humble thing to do. This was a record made by fans – we wanted to own up to being fans. And we thought rock'n'roll bands just don't do that -–we all know they are, but they don't do it. The Rolling Stones did it on Exile On Main Street, sort of, and it was a kind of role model. But we wanted to go even further and have pictures, because there's people out there who probably don't even know who Billie Holliday is, or who BB King is. We thought of it as: 'We have this thing, U2; now let's just put it aside almost, and let's just get lost in this music'. "

So it was, at least in part, a tribute album?

Advertisement

"Yeah, but it wasn't meant to be a tribute to us (laughs). It's very funny, but things like that have happened to us before, so sometimes we can utterly misread a situation. I mean, I still think it was the right thing to do. We were in there as the apprentices – it was quite obvious. You only have to see the movie to see the look on MY face of sheer embarrassment, talking to BB King, sitting next to this great blues man."

Again, Bono's introduction to the band's cover of 'Helter Skelter' – "This is the song Charles Manson stole from The Beatles; we're stealing it back" – was seized upon as evidence of alleged delusions of grandeur.

"It was a totally off-the cuff remark but it was meant in an irreverent kind of way," he responds. "I don't want to seem to be defending myself – I don't see why I have to defend myself – but rock'n'roll has always bad a little bit of irreverence. At the same time, I'm more reverent than anyone about music, about the spirit of it, about what's at the heart of rock'n'roll.

"But when you start off as a punk band in a garage, you do that everyday: you do cover versions of rock'n'roll songs and re-work them to suit yourself at that particular moment in time. And, y'know, we thought 'All Along The Watchtower' would really throw people, but then when they saw the movie they'd understand it. The idea of learning how to play a song five minutes before you play it live is one, thing – but five minutes before it appears on your album we thought was hilarious. That, for me, was the sort of thing a big band like us should do – let the air out of the balloon, not blow it up!"

In the overall context of recorded work, Bono will allow that Rattle And Hum can be "looked at the way people look at Under A Blood Red Sky – but it's something we did instead of a live album." If that suggests a sense of modesty in his perception of the album's scope and ambition, it is not, however, to be confused with any lack of faith in its content. On the contrary.

"The reason it's a great rock'n'roll record is because it has great songs," he argues. "There isn't a weak song on the LP. That's what makes a good or bad LP. The fact that it's an awkward son-of-a-bitch to listen to means that it can't be an album in the sense of 'album' with an American accent. But the songs on it... 'Desire', 'Angel Of Harlem', 'All I Want Is You'. There's no mention of 'All I Want Is You' in any of the reviews – it's better than 'With Or Without You'. We'll probably have to release it as a single before people realise that."

Advertisement

In terms of quality, he could also have singled out the magnificent 'Hawkmoon 269', but in a thumb-nail 'review' such as Bono's just delivered here, it will inevitably be his assertion that the record is bereft of a single weak track which will be picked up, and used as more fuel to fan the flames of critical discontent. Like, wouldn't he admit that the cover versions are off-the-wall?

"Yeah, they are off the wall," he cheerfully agrees. "That's the way to do cover versions. The only reason we played 'All Along The Watchtower' in San Francisco was because the gig was in the financial district. It was, like, 'let's stop making big decisions – let's make some small ones'."

The relevance of 'Watchtower' to the financial district had to do with the three lines from the Dylan song that had always stuck in Bono's mind: "Business men they drink my wine/plough-men dig my earth/but none of them along the line/ know what any of this is worth." The rest, he says, he picked up on the day.

"Literally," Bono asserts, "by asking one of the local guys, somebody walking by, if he knew the words. We were collecting them on the spot.

"The sense of humour of this band is missed a lot," he elaborates." It's like some American papers reported that we had done a Save The Yuppie concert – the same band who did concerts for human rights and for the starving peoples of Africa were very concerned about the Crash. Honestly, it was reported without irony. It was like the time lightning hit the aeroplane when we were flying into America, and we were sitting opposite Sophia Loren and I said 'don't worry, it's only God taking your photograph' and she laughed. And then the story came out in a very serious way. It's just one of those things. Maybe people don't expect us to have a sense of humour, so they don't look for a sense of humour in anything we do."

U2's choice of 'Helter Skelter' as the album's other cover version, had an altogether different significance – as its placing at the top of side one suggests. The relevance of the song's portrayal of someone turned upside down and inside out in a world gone frantically haywire, was not lost on the band, according to Bono.

" 'Helter Skelter' was exactly what we were going through on the Joshua Tree tour," he explains. "It was one of the worst times in my musical life. First, a falling light cut me up and I had to be stitched up. My voice failed for the first week – the world press came to the opening of the tour and I couldn't sing. We were on the run the whole time, and I busted my shoulder and was in a lot of pain. And I found that I was drinking a lot just to stop the pain."

Advertisement

Going on stage drunk even?

"No, I never went onstage drunk. I would've drunk but I wasn't drunk onstage. It was madness. I don't want to overstate it, but there was just times on that tour... there's this thing, y'know, we call it the heart of darkness. It was a series of four or five songs that began with 'Bullet The Blue Sky', then 'Running To Stand Still' into 'Exit' and 'Bad'. And we found ourselves in this heart of darkness, playing these songs every night, and not coming out of it, just feeling very black... we played some great concerts on that tour but there was a lot of madness."

In the past Bono spoke of the War tour going somewhat off the rails – is it a case then that this 'madness' is an inevitable consequence of massive tours?

"I think it is, and for different individuals at different times. We've agreed that we won't do one again, we'll just play when we want to play. That's the way we feel about it right now; we may change our mind. I don't want that to sound like rock'n'roll star cribbing, moaning about being on the road. There's a side of me that would go on the road and never come home, but it's the mad side and it's the side of me that after one, two, three, four, five, six months, starts to lose sight of the other. Some days I don't know who I'm goin' to wake up as.

"There's a lot of laughter as well, but there is a point when the laughter becomes hollow. There is a street-gang side to being in a band and there's a wild streak in U2 and there's a way in which a member or members can get a bit out of control on a tour and forget where they've come from, and who they've left behind. You can live out any side to your character, and there are many sides to all of our characters...

"Outsiders can come and go from the tour, and they just see four guys in a band who go onstage and play – a lot of the time – great rock'n'roll concerts. That's all they see but you can start to live out the music a little too much sometimes, where the demons you're exorcising in the songs sort of follow you home. And they follow you home to what is the padded cell of a hotel room.

"Now this will sound like utter shite, because people see a suite in the top of the hotel in Chicago and think it must be the most incredible place to be. But the more plush the surroundings, the poorer you feel in spirit sometimes."

Advertisement

In documenting the dark side, Bono doesn't want to make it sound like he's lost sight of the light. "The high of being onstage in front of 10,000 or 100,000 people," may, as he says, be followed by "the low afterwards." But the scales still weigh heavily on the positive side.

"I don't want to be the rock'n'roll star who's giving out about something he loves," he says. "Because I do love this. I wouldn't do it if I didn't."

From The Joshua Tree, through the tour of the album, to the release of the new LP and film, an increasingly strong impression emerged of a band hugely – though not exclusively – preoccupied with The Big Country.

With Rattle And Hum under his belt, can Bono now say that he's gotten America out of his system?

"I hoped living in LA for six months would get America out of my system, I hoped making Rattle And Hum would get it out of my system. But now I've come home, I'm still living in America!" he states. "We all live in America, in the sense that you turn on the television and it's America. As is a lot of the music we listen to. America slips under the door, it creeps all over you. It's something that we have to come to terms with. There are more Irish people in America than there are here... it's all mixed up, it's not as simple as America over there and Ireland over here. It's not like that. America's bigger than just the 300,000,000 people that live there. As Wim Wenders said, 'America's colonised our unconscious' – it's everywhere. So how on earth can I get America out of my system? I can't get it out of my television!"

As for Ireland, the decision of all four band members to continue living and working here is ample testament to their attachment to the old sod. However, as their collective star has soared ever higher in the rock firmament, their resultant celebrity is something over which they do not have ultimate control.

But the big fish in the small pool syndrome doesn't always work against you.

Advertisement

"If you make a mistake here, you could make a mess," Bono reflects. "I've been a bit out of hand once or twice, here or there, a bit drunk maybe at six o'clock in the morning or something, and you know, you make a mistake and you go to get into your car... Someone here is more likely to take you and put you in their car and drive you home, Irish people are like that. They don't really kiss and tell. You can make a mistake and they generally watch your back for you – I've had some experiences of that."

On the subject of the media, he expresses annoyance at "the U2 stories being printed all the time which are completely untrue." For example, he cites a recent headline claiming the band were due to record the soundtrack for the sequel to Chinatown, starring Jack Nicholson – a story, he says, that's totally without foundation. He was also irritated by the presentation in the Irish Independent of his contribution to a new book Across The Frontier edited by Richard Kearney, "They gave the impression that I was writing a book and that I had written this piece, when in fact it's from a conversation I had with Richard Kearney – somebody I respect– for his book, that Neil Jordan and Paul Durcan were also a part of."

Without naming names, he also alludes, with evident anger, to more personal attacks on him which have been published recently.

"There have actually been lies about me," he says. "People saying things like I'm a liar. I'm not sure I really want to get into it, but in the end the worst things people can say about you are not as bad as what you're really like (laughs). But I'm becoming numb to it and I'm becoming numb because I'm so strung out on the songs and the music, at the moment. It's become so loud in my life that it's drowning out all the shite that has been following us around. And the bands that are sick and tired of being compared to U2, it's amusing again, because the same bands seem to talk about nothing but U2..."

It's back to that issue of scale, and – at least until fairly recent times – the phenomenon of U2 looming extra large in the Irish context, for want of any real competition. Bono agrees. "That's why I go to bed at night and I thank Holy Mary for the Hothouse Flowers and Sinead O'Connor and Enya and all these people, because we've been out on our own and sometimes we get a bit bored and lonely for the lack of company."

He pauses. "That was a joke by the way," he adds with a grin.

But at the end of the day, can criticism hurt?

Advertisement

"It can. The sort of criticism we got over Mother, for instance, from younger bands who wanted to put us in the cliched role of being Led Zeppelin and therefore casting themselves as The Clash and The Sex Pistols, without having a thimbleful of the talent that those two groups have. To be honest, I just got less interested in that whole thing. I realised that it was actually something I could do without. I'm at a time now where my philosophy is to simplify – not just musically trying to strip things down, but in my own life trying to strip things down to get to the essence of what we want from U2. What is it about really? And in the end it's about records which are made up of four minutes, albums which are made up of some music and some statements about the way you see the world and what's going on in your life at this time. Arid trying to be – dare I say it? – artists."

And, while writing songs and making music in the context of U2, is still Bono's prime vocation, away from the group he has got some personal artistic projects simmering. The background involves his attempts to be more rigorous in his style of lyric writing. "I thought it was important at one point to write in a beat sort of way, without editing myself as I went along," he observes. "It felt very Irish, very stream of consciousness. Allen Ginsberg approved of it too! It seemed to have all the ingredients that suited my lazy bastard approach to life itself. Y'now it seemed to suit me fine. But now I am a little bit more interested in storytelling and I've started to write some other stuff – like, now, I've got two stage plays and a book in progress."

Though clearly excited by the challenge, beyond revealing that one of the plays, The Million Dollar Hotel, is set in a flea-bag lodging house in downtown LA, he's reluctant to talk too much in public about the material in hand, not least because, as he puts it: "I might never finish the things. I just work on them when I feel like it – like earlier tonight, or when I'm on the road or when I'm not in the mood for writing songs. It's all very... kaleidoscopish!"

In relation to the real life inspiration for The Million Dollar Hotel and his first hand experience of the milieu while living in LA, Bono acknowledges the voyeuristic, if not exploitative, aspects which can be involved in the well-to-do artists' mining of lowlife for creative material. "I think artists are utterly selfish creatures and I don't approve of it at all," he says. "But I can't stop being attracted to that side of things. It's probably the violence in me that got me interested in violence. The reason I'm attracted to the light of the Scriptures is because there's another side of me that is dark. The reason I'm interested in the men of peace is because I'm not like them and I would like to be. I'm not someone who in real life turns the other cheek..."

'God Part II', a song of irony and deliberate contradiction, is one of Bono's strongest lyrical statements to date, notable for a number of memorable lines, including a savage denunciation of Albert Goldman, which was inspired, it transpires, as much by his earlier book on Elvis Presley, as it was by his follow-up work on John Lennon, to whom the song is dedicated.

"Elvis changed everything," says Bono. "The America I know was born in 1956 when Elvis appeared on the Merv Griffith Show – because black 'n' white music collided in this guy's jerky dance. He had white skin with a black heart and what I love about America is the fact that its melting pot of European and African culture keeps it from going straight. I think what's really significant about Elvis Presley and rock'n'roll culture was that everything changed in America after that. Racism was broken down as significantly as it was through the peace movement and MLK – not institutional racism but common racism. It was an extraordinary event: an explosion took place. Albert Goldman missed this completely and utterly and didn't see it as significant at all."

Advertisement

Are there many black fans at U2 gigs?

"No, there aren't," Bono agrees, "though we have a lot of minorities who like our music – Hispanics, Mexicans etc. But in America apartheid exists on the radio, with black stations and white stations. We don't get played on the black stations and the white stations don't play much black music. It's partly a cultural thing and it's partly encouraged ghettoizzation."

So what made John Lennon stand apart in Bono's eyes?

"It's enough that he was an influence on my own musical life, never mind talking in terms of youth culture as a whole," he replies. "He had an incredible cut-throat honesty to his music that I always looked up to. He was saving this is what I think, so here it is. Some people write about the country they live in – Lennon wrote about the mind and the body he lived in.

"I'm the sort of person who absolutely despises what Goldman did," Bono adds, "yet still reads the book. I had one advantage coming to it in that I never thought of Lennon as a hero really, more as an anti- hero. Also, when the book came out Jimmy lovine was reading it in the studio and he knew John Lennon, so Jimmy could point out where the guy (Goldman) was completely wrong. The bit about Spector and his body guards tying up John in the house: Jimmy was there–- he untied him but he wasn't in the book. It's laughable. I got an accurate picture of who John Lennon was through Jimmy lovine. He saw him for the good, the bad and the ugly that he was. Personally I've got so much respect for him as a man and as an artist."

Who, if anyone, qualifies as a hero for Bono these days?

"I don't have heroes like I used to have, because I've met a lot of people who at 16 I would have called my heroes. But in a way, having met them, they appeared even more heroic to me because they were flawed. I suppose I suspect people who don't have flaws – it's a feeling that there must be something wrong somewhere. I don't negate one side of the person because you know there's another. Anyway, the people I'd look up to tend to be older. In music and in literature. Jonny Cash is a hero if you want to use that word. Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, Lou Reed, Keith Richards. These are people who survived rock'n roll and came out the other side with interesting stories to tell to someone who's going in."

Advertisement

In those terms, Bono may still count himself an apprentice, but there's no gainsaying the fact that he is himself an object of hero-worship to many. In 'Love Rescue Me', the song he co-wrote with Bob Dylan, it's a theme that seems to be touched upon in the line 'They asked me to reveal the very thoughts they would conceal" – a statement, one could suggest, that had equal relevance for Dylan and Bono. So whose was it?

"The line is mine I have to say," says Bono, "but it's not about people coming looking for salvation – it's more about people wanting to look into your soul. There's also the aspect of the performing monkey syndrome – like those Victorians that used to arrive at Bedlam and poke the demented creatures. (Launches into hilarious toffee-nosed commentary). 'There's Iggy Pop in there now, look at him, he's cutting himself. And there's that Johnny Cash – he's an alcoholic and he's on pills at the moment. Bob Dylan – he had a motor cycle accident. He was a spokesman for a generation and it was all a bit too much for him'. Poke poke poke. 'Now here's Bono, he's going to talk about God and Northern Ireland and sex – all at the same time. That's his trick'. Whack on the head!"

In Rattle & Hum the movie, the combination of music and emotion is at its most powerful in U2's performance of 'Sunday Bloody Sunday', filmed in concert on the day of the Enniskillen bombing. Subsequent to the film's release, Bono has been heard to ponder, on more than one occasion, the possibility that the band won't play the song again. Why?

"Because it's almost like that song was made real on the day," he reflects. "It was made real for the moment, in a way that it's never going to be again. I think that that was the ultimate performance of the song and anything else would be less than that."

Had he ever hoped, in originally writing the song, that it might contribute, in however small a way, to decreasing the likelihood of the kind of events it depicted, being repeated again and again.

"No, not really. I suppose in the back of your mind you hope you can help, and turn things round in some way, but that's not really your job as a rock'n'roller. Your job is to write a good song that expresses how you feel, how you see things. An experience I had, a very interesting experience which shows you how far and wide an audience can be in their understanding of U2, was when we played Belfast last year. It's got to be one of the greatest rock'n'roll cities in the world but we didn't quite know what they'd make of 'Sunday Bloody Sunday', after it had had a few years to sink in.

"As soon as we started into the song a tricolour shot up. Then a Union Jack shot up. Next thing, the Union Jack was pulled down and the Tricolour was pulled down by other people in the audience. Then some people in the front row started giving us the 'fuck off' sign. But as soon as the song ended and we went into another one, the same people went crazy and got straight into the next song. And I thought that was very interesting – that you could hate a song or something that U2 did, but still love the band."

Advertisement

Has he experienced any particular reaction to the song's introduction in the movie, the 'fuck the revolution' speech?

"No, I think people understood where it came from, that there was a good reason. It was a reaction. It was taken not so much as a political statement, but as an emotional one which a lot of people shared, including some supporters of the Provisionals, I would have thought. Everyone would have felt that way."

There have been press reports nonetheless that Bono has received death threats from the IRA because of his statement. Is there any truth in these?

"No. What I ask is: if you really hate me or hate U2 don't shoot me – that will only sell another 5 million records! Know what I mean? Like, I'm worth more dead than alive! If you really hate me don't make me a legend!"

Bono finds it disturbing, at the same time, that a story like that should have made it into print.

"Yeah. In fact, I was sitting on a plane opposite Robert Maxwell and I hit him with it between the eyes. I said 'Your paper printed some lies about me and our group. Lies that were harmful, that could have put an idea that wasn't there in somebody's head'. But then I get death threats all the time. Everybody receives death threats in a big rock'n'roll band. We've had them, we'll have them again."

Understandably, it's not a subject he likes to dwell on. Talking about the North, however, he's more expansive.

Advertisement

"With regard to the IRA, I know some people think 'he's got no right to talk, he doesn't live in Derry, he doesn't live in Belfast'. But I have the same right to talk about it as anybody in the pub. Even if I wasn't in a band, I'd be talking about it, and I have a right as an Irishman to have an opinion. And not even as an Irishman – I just have a right to have an opinion."

While placing on the record his opposition to the legislation banning Sinn Fein from the airwaves in Britain, he remains unshaken in his belief that the armed struggle is wrong.

"I think that the argument that the Provisional IRA puts forward, apart from the moral side of the issue, is just unintelligent – an unsound and old-fashioned idea that may have had relevance in the past but doesn't now," he says. "Revolution, where the overwhelming majority of' the population are not behind it – and they are both a minority in the North and a minority in the South – won't work. Also, revolution to turn us into what? I don't think they have a political agenda in the real sense of the world. I don't see a real vision of the future that we could all buy into."

What about the withdrawal of British troops as an immediate item for negotiation?

"Yeah. I'd like to see that. In fact while I speak out about the IRA, I've also spoken out about the British presence in Northern Ireland on BBC Radio a few weeks ago. I said they don't want to be there and they shouldn't be there. It's obvious that Ireland is an island... The idea of borders is a bit dodgy anyway, not just between North and South but between anywhere.

"I think John Hume is the man with real vision. He realises that there is a bigger Europe that we are a part of, and we'll become closer – the North and the South will become closer – by both becoming part of a bigger Europe, a bigger world, with a bigger vision. It's so small, the vision of 'Ireland' and 'Eire Nua'. Who cares about Eire Nua? What about Europe Nua? The World?"

Can he understand or appreciate the motivation of someone like Bobby Sands?

Advertisement

"Yes I can, and I must say that you can't but be in awe of the strength of will that it took for Bobby Sands to go on that hunger strike but I just don't know – there are people striving to hold on to life. There are people in other countries who are dying because they have no food, not because they are refusing food. To me, their reality is something that we must not forget about.

"I don't deny that some of the wishes of the IRA, and some of the people who support the Provisional IRA, are sincere – but they are, in my opinion, sincerely wrong."