- Opinion

- 19 Apr 21

Irish Music Industry in Lockdown: "We Need A Plan"

In lockdown for over a year, musicians, and everyone who works with them, have been suffering disproportionately as a result of the restrictions imposed in Ireland, in response to Covid-19. Many have not just been left without an income but also shorn of a sense of purpose. The biggest frustration is that there is no evidence of a plan as to how the industry can be resuscitated – because the health authorities seem immune to understanding the colossal scale of the damage being inflicted... Illustration: David Rooney

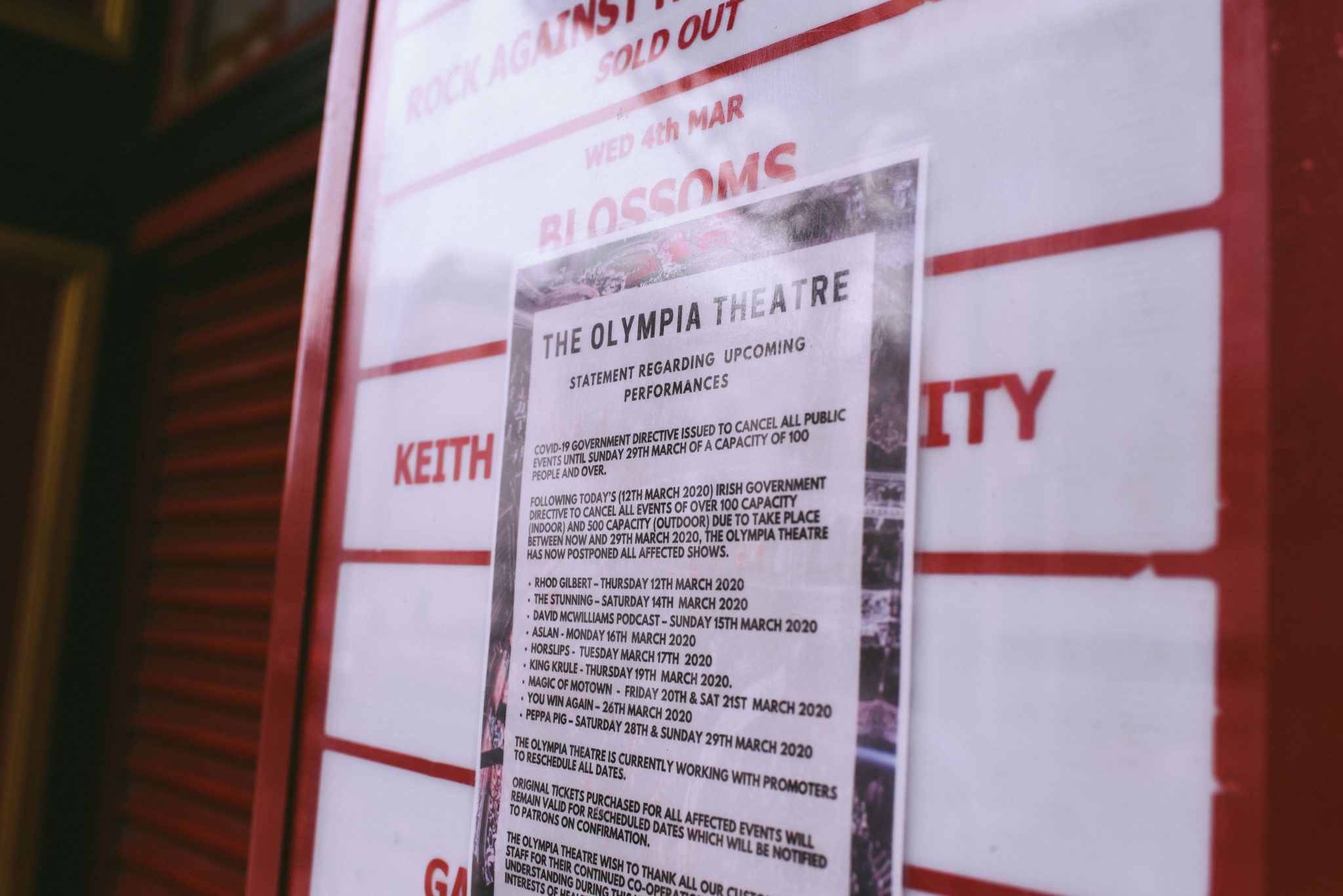

No one knew just how bad it was going to be. It is 13 months, more or less, since the first lockdown was announced in Ireland by the then-Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar.

The Taoiseach’s announcement was not entirely unexpected, but it was dramatic nonetheless. There was a sense, in March 2020, of history in the making. We just had no idea how much our story was about to be rewritten.

Collectively, there was an assumption that it would be a matter of weeks, rather than months, before we’d be back to normal. “What do you think?” people would ask. Playing it cautiously seemed like the better option. “Hopefully everything will be up and running again by the start of June,” you might answer. “The festivals should be alright.”

Of course we knew nothing then. About PPE. Pandemics. Immunology. Viruses. Disease transmission. Herd immunity. Variants. Viral loads. Hospitals being over-run. People being very scared. People being very, very scared. Level-5 restrictions. Road maps with little or nothing on them. Loved ones lost. Isolation. Quarantine. Loneliness. Fatigue. Long Covid. Death stalking us on the news every night. A general, mounting sense of just how completely fucked up this whole business is.

Dread in our heart’s core. Every morning. The same feeling.

INESCAPABLE TRUTH

We were not alone in being ignorant. Governments were making it up as they went along too. Under the risibly ignorant, childishly bumptious leadership of Boris Johnson, our neighbours in the UK got it spectacularly wrong. The death toll there rose precipitously. The government engaged in a massive cover-up. Deaths were ‘mislaid’. But still they raced to the top of the global charts, the world’s undisputed No.1 for mortalities.

In most respects, Ireland did better. The lockdown(s) dragged on but we seemed to be making the right moves. Up to a point that is. The longer it went on, however, the harder it became for people to cope. In the beginning ‘We’re all in this together’ was the mantra. Gradually, it became clear that this was not the case. Far from it.

You could be working in Facebook or Google, as a politician or an inspector in the Department of Agriculture, and you’d be secure. But pilots were getting their marching orders in big numbers, right across Europe. How was that fair or equitable? It wasn’t. And it isn’t.

Not that pilots were the only ones. In the hospitality and entertainment industry in Ireland, people were being put out of work – by the health authorities and, some people argued, by the ideological zealots of NPHET. Businesses were closed. Many of them started to become very aware that they were facing possible extinction. Many of them still are.

Towards the end of 2020, the Government blundered badly. A lot of people think they were wrong to allow hotels, restaurants and bars serving food to re-open. In truth, however, it was the messaging that was most at fault. They trumpeted that they wanted people to have as normal a Christmas as possible. I knew immediately: it was chronically ill-advised notion, fashioned out of a desire not to be seen as a bunch of scrooges.

It was a moment when a gentle loosening might have made sense, to enable people a bit of badly needed oxygen, and retail outlets and restaurants to maintain the connection with their customers and make a few quid. But the way it was presented by the politicians gave some dimwits a license to go crazy – and they did. The result was catastrophic. The arrival of the so called UK variant made matters worse. Infections soared. We were back to where we started – only deeper in the mire.

Live music never did get an opportunity to return. In the latter half of the year, the Department of Tourism, Culture, the Gaeltacht, Sport and Tourism mounted the first Live Performance Support Scheme, which worked well. It put a substantial amount of money back into the system. There were no crowds, but musicians got paid for doing gigs. So did crew. The hope was that when the scheme was over, crowds would be allowed into venues again. Instead, it was back to staring at the walls.

And that has gone on and on and on. We have endured the longest lockdown in the world, which is surely an indictment of the way in which the health authorities have gone about their response to Covid-19 here. And at least part of the reason for the oppressively elongated nature of it is that it is too easy now for the health authorities to insist.

Would they be able to impose on the Gardaí that they have to live on €350 a week? Not a chance. But hairdressers don’t have the equivalent clout. Neither do musicians.

And the inescapable truth is that, in just about every respect, the impact on the lives of working musicians, and the back-up teams that support them, has been devastating.

Dublin during the Covid-19 outbreak. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Dublin during the Covid-19 outbreak. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.THE GREATEST HARDSHIPS

Is it possible to convey just how disastrous the imposition of restrictions has been? No one is disputing that pubic health should come first. But to those working for trillion-dollar companies that means one thing: if your income is unaffected, then the rest is just an inconvenience. Not a small one: in fact there are times when, even to workers whose wages are completely secure, the whole charade puts a fierce strain on people’s mental health and their ability to get through a week.

But it is an entirely different matter when – in effect by order of the National Public Health Emergency Team – you are told that your job is gone or your business has to close.

The Government introduced measures to soften the hammer blow, in the form of the Pandemic Unemployment Payment and a variety of supports for business. At least, as the fella said, it was something. For many, these measures worked reasonably well. But, looked at in the cold light of day, for a huge number, it was totally and completely inadequate.

There are music industry professionals operating at the top of the profession, earning good money, who had mortgages and other commitments to match, and who were told unceremoniously: shut the doors and get out of there. And who have not been in a position to earn a red cent in the interim, but have been forced to exist instead on €350 a week.

What would have happened if teachers had been plunged into the same dystopian nightmare? There’d have been war. So if it would not be okay for teachers – and it rightly wouldn’t – why is it just hard cheese for musicians, lighting designers or road crew? Or indeed for the people who have been running these businesses, in some cases for decades? Why is it okay that the man or woman who books gigs for any one of the hundreds of venues all over Ireland that people attend to be entertained and uplifted, can no longer earn a living or maybe even put food on the table?

Why is it okay that Coughlan’s in Cork or Mike the Pies in Listowel has been shut for over a year now, with no clarity still as to when the show might be able to get back on the road? Why is it just too bad that the musicians who play in wedding bands – and in many cases earn a good living from it – have to go completely without, their income shrivelled to nothing?

A lot of people in the music industry – and throughout the hospitality and entertainment industries – feel that there has to be some kind of reckoning, a moment when the burden of the torture inflicted is redistributed, and shared equally across all areas of Irish society.

That may be a forlorn hope, but it is not an unreasonable one. Which is why the emphasis in public policy has to be on doing far, far more. This is not about the Department of Tourism, Culture, the Gaeltacht, Sport and Media. Behind the scenes, they are fighting for every cent they can get for the arts and culture sector. They and Minister Catherine Martin are supportive of the recommendation of the Arts and Culture Taskforce for a Universal Basic Income for arts workers, including musicians. All of that is good.

It is about the approach of the Department of an Taoiseach, the Department of Finance, the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform and the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment And it is also about the willingness of the State to borrow, and the skill of the teams that are charged with that task.

How can we possibly put the broken pieces back together again for businesses? How can we enable individual workers and businesses alike to get back to more or less where they were?

For some – whose owners have died or reached retiring age – the unlucky tide of history will not allow it. They are done. There are others too, for whom the mental toll proved just too much – who are on the floor and who just don’t have it in themselves anymore to fight back. How can they be compensated as they should be?

But there are others who would have the professional capability and the personal resilience and ambition, but who need time – and who should not have a mountain of debt imposed on them. There can be no doubt that they are entitled to equity with other members of Irish society. The question is being widely asked in music now: why should one class of people suffer excessively?

It is a question that very few people in authority have been framing in that way, but that needs, in all fairness, to be answered. Why should pilots or musicians suffer disproportionately? Why should the entrepreneurs, promoters, events organisers, sound and lighting providers and all of the rest of the people whose livelihoods have been closed down be forced to eat from a can while other people build up their savings accounts?

In all of these things, musicians, and those who work in and around the music and entertainment industry – and indeed in hospitality – are entitled to fairness. They are entitled to have the value that has been battered out of them by the pandemic restored.

There is a way. And, in its crude form, that is to borrow enough money to fill the value gap. To target effectively where that should go, in a way that obviates the need for business owners, or individual service providers, to borrow money. And then to retrieve that money through general taxation, over the medium to long-term. This would be an equitable solution: that in the longer run, we all contribute our fair share to getting things back more or less to where they were for individuals and businesses.

Lisa Hannigan and John Smith gig at Windmill Live in Windmill Qtr, Dublin. Thursday 12th of December. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Lisa Hannigan and John Smith gig at Windmill Live in Windmill Qtr, Dublin. Thursday 12th of December. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.TIME FOR GETTING IT RIGHT

These questions seem more pointed than ever just over a year after the first lockdown was announced. Musicians have been bearing the brunt. Which is why we decided, in this issue of Hot Press, to take a closer look at the devastating impact that Covid-19 has had on the vast majority of people working in the music space.

Not everyone has been equally badly hit. Among the people we approached to contribute, there were some who said that they’d prefer not to comment because it might seem as if they were gloating. But their number is tiny. For the vast majority, it has been an unrelenting disaster.

It isn’t just that they have been starved of income. In so many respects, musicians have had their great joy and motivating force stolen from them. They have been denied the connections and routines that give shape and meaning to their lives. They have lost out on an entire year of friendship and camaraderie, of laughter, celebration and love.

They have been denied the quiet moments together before they go on stage. And the time afterwards to unwind and start to look afresh at what comes next: to dream of a future in which art, music, songs and musicianship count – really count – for something again.

It is impossible for anyone outside the cultural sphere to understand the extent to which the heart has been torn out of it.

Speaking to Hot Press recently, the brilliant Lisa Hannigan mused on just how much it would mean to get back to standing up in front of a crowd again, the way – as a musician or a performer – you did, before all this strangeness, as she put it, descended on us.

To a musician, that is what matters more than anything else in the world. Maybe, in truth, not more than the love of a wonderful partner; or, probably too, not more than the joy that our children give us, as – in the process of growing up – they demonstrate just how extraordinary and brilliant other flawed and vulnerable human beings can be and are.

But the joy of playing is the source of a musician’s heartbeat. It is the focus of their creativity, and their ambitions. It is the fuel that keeps them going through the winter months. It is an ocean’s worth of joy and sadness in an hour or ninety minutes. As watching the marvellous Wallis Bird will inform anyone with ears, it is at once a place where we can be both playful and powerful, fiercely emotional and just plain funny.

Playing live is the field of a musician’s dreams. It is an escape. But it is also reality at its most resonant and beautiful.

It is notes sailing into the evening sky. It is a voice alone in a room. It is poetry and pleasure.

It is work. And yet it is the ultimate freedom, making the melodies dance and skitter off into the surrounding darkness at a festival before descending into the beauty of silence. The voice calling out. And then appreciation. Applause.

It is long past the time to get our musicians working again, weaving magic as only they can. There are so many reasons to be optimistic about the creative strength of Irish music right now. It is a river, deep and wide. But we need a plan. And, in the long run, everyone in this space is entitled to equity. The time for getting it right is now.

• 'Music Industry in Ireland: Where To Next?' is a special feature in the new issue of Hot Press, running to over 20 pages, featuring music industry professionals as well as artists including Moya Brennan, Jess Kav, Luka Bloom, Fia Moon, Kneecap, Gavin Glass, Mick Flannery, King Kong Company, Mary Coughlan, Rosie Carney and many more.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 16 Dec 25

The Irish language's rising profile: More than the cúpla focal?

- Opinion

- 13 Dec 25

Trump’s assault on Europe: "Happy new year? Somehow I don’t think so..."

- Sex & Drugs

- 11 Dec 25