- Music

- 04 Mar 19

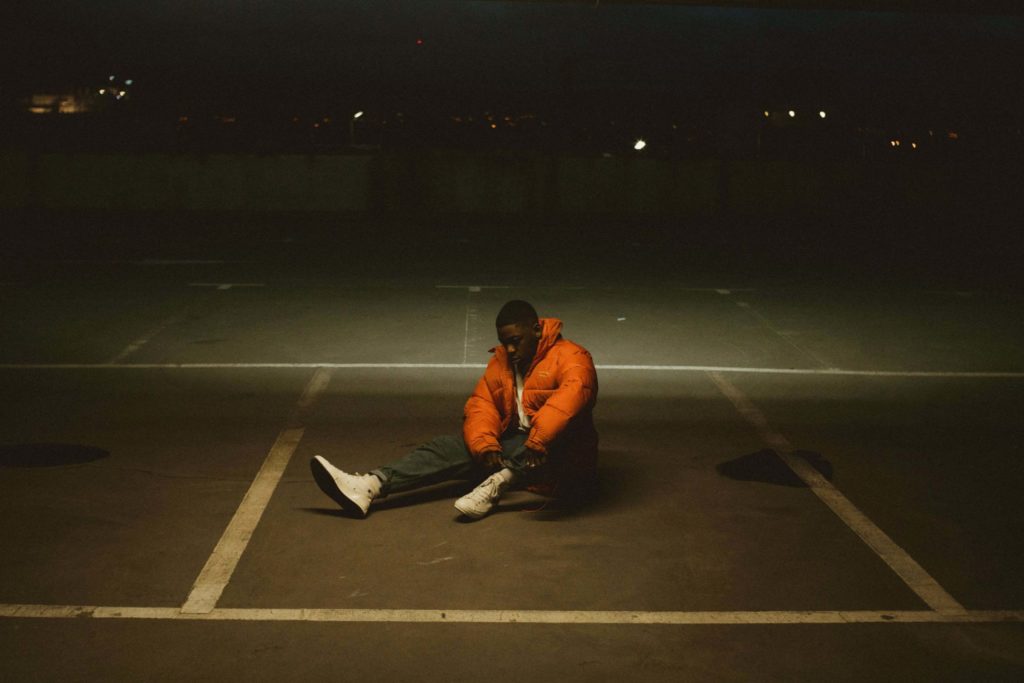

From Church halls to festival stages, from starring on the silver screen to being given pride of place on major Spotify playlists, Percy Chamburuka, aka Jafaris, has muscled his way to the forefront of Irish music. The rapper/actor talks to Peter McGoran about God, family, his African heritage, confronting his ego, and the concept behind his fascinating debut album Stride.

Rap and religion don’t immediately strike you as close bedfellows. When it comes to rap, there’s a perception of hard-edged verbal sparring. There’s a reputation of celebrating hedonism, crime, or excess. With religion, there’s piety (at least the veneer of it), rule-based systems, authoritarian organisational structures.

Still, Jafaris – the rising 25-year-old star of Irish hip-hop – isn’t shy about stating that faith in God is one of the most important things in his life. Indeed, he was introduced to hip-hop through his church.

“I started dancing when I was 10 up to about 16, 17,” he explains. “Then there was that transition into music, because a very close friend of mine started doing it out of nowhere. He told me, ‘I’m rapping now’. This was when we were in church.

“He showed me his stuff and I was super interested. I looked up to him as well, so I started wanting to do it. Obviously, I began with the influences of 50 Cent and Lil Wayne, so I would’ve been talking about what they were talking about in their songs. And then it transformed from that into spoken word stuff, before I started rapping. The spoken word thing allowed me to say exactly how I felt through rhyme. Then that became rapping over beats, and eventually I started coming up with melodies. Now it is what it is.”

Jafaris’ late teens and early 20s saw him become a jack-of-all-trades. As well as dabbling in music and spoken word under the moniker of ProFound, he had a starring role in John Carney’s Sing Street in 2016. He also briefly studied Business Management at IT Tallaght and songwriting at BIMM.

Advertisement

But real life was moving faster than academia for the man born Percy Chamburuka. He was playing gigs in his own right, developing his reputation as a serious musician, and when he teamed up with Diffusion Lab – a Dublin-based music production group specialising in hip-hop, 2-step and R&B – Jafaris began to take things seriously.

“I met with Diffusion Lab two years ago, when I did a feature with Precious from Super Silly,” he explains. “We did a song and at that time I was pretty shy, so I didn’t talk. Then a few months later, another friend of mine wanted to record there. That’s when me and the producer started creating a relationship; we had a similar interest in music. Then Ivan Klucka – who runs Diffusion Lab – stumbled upon a show of mine in the Workman’s, and was like, ‘I’m interested’. We arranged a meeting and all this started to bubble up for me.”

When did the name change come about?

“Things were going well when I was ProFound. But there was another ‘Pro Found’ from the UK – who was already somewhat established – and his manager contacted me through a YouTube comment. He said, ‘Yo, we have to battle for that name! We already have an artist with that name!’ I saw that, and I also started noticing that it was getting harder for people to find my music, because there was other Pro Founds, so I just started thinking of new names. I already had Jafaris in the back of my head, because I remember it was one of the first names that came up when I put in ‘names beginning with J’ on Google. It meant ‘a deeper need to inspire’. That’s something that I aspire to.”

Jafaris’ musical pursuits, as well as his decision to quit college, meant that he received pushback from his parents.

“I had to really sit my family down,” he reflects. “I had to construct the whole five-year plan of what I was doing. My mum didn’t take it so well, because her dream was, ‘Oh my son’s gonna graduate.’ But I just said, ‘Yo, this is where my heart is. This is what I’m passionate about.’ I already had it in my head that I was gonna do it with or without their blessing, but they’ve definitely come around now.”

Advertisement

UNDERGROUND HIP-HOP

When Jafaris started getting into music seriously, almost five years ago, he encountered a network of artists similar to himself throughout Ireland. Undiscovered at this point, many of them have become integral to the Irish hip-hop scene.

“As a teenager when I started rapping, there was a communal vibe but no one knew about it,” he notes. “There were shows in hotel function rooms, shows in churches that people rented out for a day. There was a lot happening. Then I got acquainted with a guy who was a music manager who knew people like G-Tribe. There was a scene of artists coming up, so I linked up with him and he allowed me to do my first club show. There was loads of little things happening, and everybody was there. People that everyone would know now, like Hare Squead, Super Silly, they would’ve been there. We were all still learning then, we were all still kids. But there was definitely a vibe of ‘We’re coming up together.’”

There’s an uncommon intersection between religion and rap, church and clubs, in Jafaris’ background. How important is God for him?

“It’s basically my lifestyle,” he acknowledges. “I put it on a high pedestal because of my experiences. I’m not perfect. It’s not something that I’ve mastered or understand to the full degree, but it’s something that I understand is important to my life – because anything that’s in my life has come through God. I put a lot of focus onto God and I ask for certain things. Not even just for the accolades, just for life – for breathing, for everything that brought me to this place I’m at now. These gifts aren’t mine, you get me? That’s why I put it on such a pedestal. But also, I grew up around religion. My family was super religious and even a lot of my friends are super religious, so it keeps me in that mindset.”

Many Irish people would be embarrassed to say they’re religious.

“I guess if I was like… hearing all these things online about priests and even the Church…” He pauses. “You know even me, as a Christian, the Church is just something that I even feel weird talking about, because the Church doesn’t – and this is the misconception – the Church is supposed to represent God. But it’s represented Him very badly, and pushes people away from God, even though God is not advocating for the things that they do in His name, you get me? Religion is supposed to be a relationship between you and God, not what they do in the name of God.”

Advertisement

Rap music and churches don’t normally go hand-in-hand...

“Yeah there’s a bit of that,” he laughs. “Like when we started doing things in churches, some people shunned what we were trying to do. A lot of the churches would have pastors who said, ‘Ahhh, well you know, God’s against this, God’s against that’. It took us finding God for ourselves to say, ‘No, we were given these gifts from God, we were supposed to use them.’ It’s not about how you present the message, it’s what the message is. That message can come through in many different ways, you get me? That’s what some pastors and people had to understand.”

STRIDE

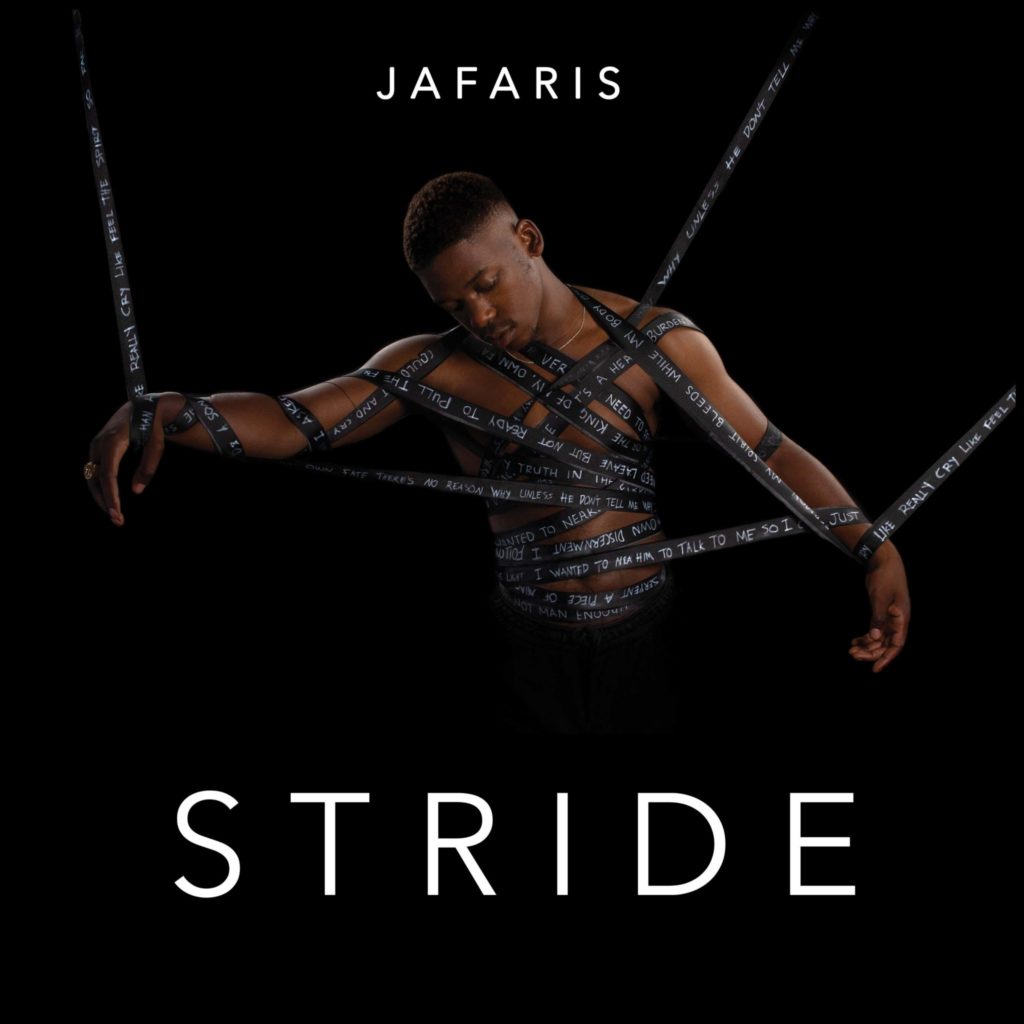

Having released an acclaimed EP and flirted with breaking into the mainstream for a while, Jafaris will release his first comprehensive body of work in March. When did work first commence on Stride?

“After the Velvet Cake EP, I was making that many songs that my manager kept pressing me to make an album,” says Jafaris. “I wanted my first album to be something that was memorable to me, but I had no idea what the process was for making an album, so we just started making songs, with no direction. Some were in mind for the radio, some were trying to stand out.

“Then I remember I was watching a sermon on YouTube called ‘Stride’. And it was talking about how, in a Christian respect, you have to walk in the path of grace, because trying to do things yourself don’t always work out; we’re always trying to figure things out. Only the Creator can explain the creation, you get me? And it resonated with me, because the previous year I was trying to do everything. All the shows, all the festivals, all the music. I was fast-pacing it. But I was neglecting friends, family, health, my girlfriend. So when I heard that, I thought, ‘That’s the first thing I wanna put in this album.’ Then it started taking a shape of its own.”

Advertisement

The first half of Stride acknowledges these things that Jafaris neglected, while the second half is addressed to the future Jafaris, the egotistical Jafaris, the prideful Jafaris. It’s a confrontation with the various parts of his being. As a whole, it’s a powerful statement about self-discovery.

How difficult was it to get into a space to confront his demons, as he does on the first half of the album?

“I know a lot of people think, ‘Are the concepts gonna be this? Is the melody gonna be this?’ before they even put pen to paper. But the reason why I put a lot on God is before I write a song, I just pray. Then things come out that I didn’t even realise were in my head or in my heart. That’s why music is more than just making money and being successful for me. It’s therapeutic in a big way, because it allows me to speak to something. Speak to myself and about myself.”

What’s the hardest thing he’s had to overcome in his life?

He thinks on it for half-a-minute. “This is personal now, but I’d say building a relationship with my dad. When I was younger, I had a huge conflict with my dad. Especially because of the music thing. And my dad’s a very… He’s African, Zimbabwean, and he’s very cultural and traditional – certain things have to be done a certain way. And he needed time to understand that things can be done a different way from what he’s known. And for me, being in Ireland, and being detached from where I came from, I was always butting heads with him.

“So it was only last year, when I went back to my country with my dad, that I started communicating with him properly and letting him know how I really felt. And he could tell me how he felt. That was the hardest thing, to get to that stage. Because I’d done things that’d hurt him and he’d done things that’d hurt me, and we got to that stage where we could apologise to each other and talk, with no egos attached. Say, ‘You’re my dad. I’m your son. Now let’s build a relationship that we’ve never had before.’ Now we’re in a good place.”

Advertisement

IRISH RAP

Over the past year alone, Irish rappers like Kojaque and Rejjie Snow have opened up about being more in touch with themselves, and rejecting old ideas of masculinity that might’ve been found in rap music before. How important is that?

“Very important man, very important,” nods Jafaris. “But I never put it down to ‘me being masculine, me being feminine’ – it’s just me being me. I’m that type of person where I’ll let people know the deepest part of me. People can learn what I’ve been through and when you share something with somebody, it allows them to share things with you. I don’t put it down to ‘being macho or not’, it’s just having a real connection with people.”

Does he think it’s important to rap in his own accent?

“I’m blessed because I have the accent I have,” replies Jafaris. “It’s not too Irish and not too Zimbabwean. I know that was a conversation in Ireland at one stage: ‘Oh, why are we Irish rappers not using our Irish accents?’ I’m just using the accent I speak in. I’m not trying to be anything more than I am. Not trying to be Zimbabwean any more than I am. But what I do think – and this is a conversation amongst other artists too – is that we definitely need to embrace the culture more. It’s hard to pinpoint what the culture is, when we all come from different cultures, but I wanna add more references to what happens here, as opposed to talking about random things that everyone would know. I wanna talk about things that only Irish people could pick up on – the Quays, the M50, things like that – so that people can pinpoint, ‘Oh yeah he’s from here.’ But not being defined by it either.’”

There’s a case being made that mumble rap and mass-produced hip-hop has made the genre a bit soulless. Would he agree?

“Soulless? That’s a mad way to put it.”

Advertisement

Maybe not soulless – generic.

“Yeah, 100%. I agree.” He shrugs. It is what it is though To be honest, everything that they’re doing now, it’s just packaged different, but it’s always been there. There’s always been people talking in the same way as the trap people are now. Whether it’s about drugs, guns, girls, all of this, it’s the same message, but it’s just different sonics. And yeah, it is generic. But I think it’s also a good thing in a bad, weird way, because if we didn’t have all of this generic rap, people wouldn’t be able to pick out artists who aren’t generic. It works hand in hand.”

Stride’s stand-out, ‘Shanduka’, involves Jafaris having a conversation with his own ego, and could easily be a companion song to Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly track ‘u’. Where did the concept for that come from?

“So ‘shanduka’, in my language, means ‘switching up’,” he explains. “It’s that moment where I first have a conversation with my ego. And my ego… I think of this like a film in my head. ‘Shanduka’ is the first time my ego is presented on the album. It’s the first time you hear his words, his voice – that’s a real battle I’ve gone through. Because all of this music stuff comes with a lot of praise and people saying, ‘You’re amazing!’ all the time. That’s great, but it puts you in a space where you start to say to yourself: ’I am the shit. Yeah, I am, aren’t I?’ I definitely had moments where I felt like that. But I had to attack that before it could become a thing. And that’s where the song came from, it’s a back and forth between my ego and I.”

How much was he trying to bring Zimbabwean culture into his music?

“It was around the time I went to Zimbabwe that I was thinking, ‘I’m very detached from my culture and my people.’ I started noticing how I wasn’t shouting about the country as much as I was about Ireland. And that bothered me. Other people I knew from there would say, ‘How come you don’t say anything about your culture?’, and I had to think about it. I have a bit in the album between ‘God’s Not Stupid’ and ‘Shanduka’ where my family’s singing in the song, and they’re singing my language. I recorded that in Zimbabwe, not really thinking that it was going to make the album. But when I was listening back, I was like ‘I need to put a bit of my culture back into it.’”

Jafaris’ music also reached a wider audience with a series of ambitious videos for his single ‘Found My Feet’ – which saw him skydiving out of an aeroplane – and ‘Time’, which boasted a gorgeously shot clip made in LA. Was the idea to always incorporate a strong visual element?

Advertisement

“Yeah, when I first met Ivan, and he decided he wanted to be my manager, the first thing I said was, ‘I’m a visual artist.’ I want the music to go hand in hand with the videos. Because I know people listen to lyrics, but don’t always pay attention. So the reason I put so much weight on the videos is because it’s the only way people understand exactly what I’m trying to say. And when I met Nathan Barlow [director and frequent Jafaris collaborator], he was the only other person who was seeing my vision to the full extent. Even with the very minimal budget that we had for each video, he’d always go the extra mile.”

The day before our interview, Jafaris was in London meeting with labels and talking about potential deals for the future. Spotify has taken a big interest in the rapper, parachuting his music onto some of their top new music playlists, while his debut album is likely to land critical acclaim. What’s the long-term goal? Sign with a major label? Go independent?

“We’ve been having a lot of discussions lately,” he says. “I came into the game with that whole Chance The Rapper mindset – do it independently – because I thought that was so impressive. But obviously you need backing of some sort to reach the masses. The most important thing for me and my manager is that no matter what we do, we keep the music ours; we keep the rights. And whatever other aid that we can get, as long as it’s mutually beneficial, then that works for us. As well as that, I wanna evolve that into other things eventually. I’m very A&R minded. I’m always listening to new artists. I’m always trying to find out who’s new in Ireland. I wanna get to a place where my voice matters, so I can bring other artists up with me.”

Stride is released on DFL Records on March 9. Jafaris plays the Button Factory, Dublin on May 3.