- Music

- 19 Jun 24

James Vincent McMorrow: "I never got into music to be successful, which I know is a ridiculous thing

On the eve of his seventh album Wide Open, Horses, James Vincent McMorrow discusses formative years, major highs, rocky lows and his remarkable creative process, as he guides Will Russell through his extraordinary life in music.

It was late in the day at Hot Press HQ on Capel St., when singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist and producer, James Vincent McMorrow, sat down with me to discuss the creation of his seventh album Wide Open, Horses. What followed was rather extraordinary, the interview developing into an extremely erudite and incredibly honest career retrospective, by a man who is an artist with a capital A.

His openness surprised me. Obviously, a big kahuna in the music game – with over 1 billion streams across an expansive catalogue and sold-out tours on multiple continents – James was candid, frank and modest.

In 2023, JVM booked two nights at the National Concert Hall in Dublin, recorded a handful of lo-fi demos, practised the material for a week, and then hit the stage. Phones weren’t allowed, but James recorded it to “see what worked and what didn’t.” This process was the foundation of his new album Wide Open, Horses.

“The premise was to re engage with music in a way that made sense to me again,” James explains, “I just don’t think for a while there, I knew what I was doing, or what I was supposed to be doing.”

McMorrow stopped touring in 2017, a year in which he performed over 80 shows. His little daughter Margot was born in 2018 (wonderfully, she has a co-write on the album, more of which anon), and he signed a major label deal for the first time.

“It didn’t really work,” he admits. “I never got into music to be successful, which I know is a ridiculous thing. Obviously, you’re ambitious musically, but you don’t think beyond that. But success really changes the parameters, it becomes about money and corporate shit. And that’s just par for the course.

“But it evolved into something I just didn’t really recognise, and a version of myself that I didn’t really appreciate. I didn’t really like what it was, just on a fundamental level. That’s a long-winded way of saying that, when I did the National Concert Hall shows, it was because I needed to do something with real stakes again.”

The idea for the shows evolved after an Electric Picnic performance of his that he didn’t rate highly. He found himself needing to rediscover a version of himself in music that he really recognised.

“It was just a thought experiment that could go horribly wrong,” he says. “But doing it this way was the only way I could end up with the record I’ve ultimately ended up with.”

James Vincent McMorrow. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

James Vincent McMorrow. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.Playing songs live that absolutely nobody has ever heard, especially when you have sonic blasters such as ‘We Don’t Eat’, ‘Get Low’ and ‘Higher Love’ in your canon, takes a particular restraint, indeed a particular artistic zeal – some would even say a kamikaze attitude. I wonder how those new songs landed?

“I wasn’t very analytical at the time,” he relates. “There were maybe two songs I played that I knew were not going to end up on the record, but the other songs immediately felt like, ‘Okay, we’ve got something here.’ Not to sound too silly, but it really transcended into something that was more like a communion.

“Those 3,000 people that got tickets for those shows, they saw something that will never exist again. They can only recall it based on what they remember, because they can’t go to their phones. It’s such a wonderful thing that you have to draw on memory to recreate these things.”

Remarkably, James himself never listened to the audio recordings of those shows.

“I had an intention to listen to all the audio, but I haven’t listened to any of it,” he clarifies. “Because the memory of it actually felt very compelling. We went to the studio really quickly afterwards, and laid down what I knew was the good stuff.

“It was whatever we played drum wise, guitar wise, anything wise, that felt locked in. I had expected to really analyse it, but that would have been counterintuitive to the point, which was to make something catalytic, which felt buzzy and responded to the situation in real time.”

Watching James talking about those shows, you sense the spark that they provided emanating from him. He alludes to some of his previous shows being contrived and static. It’s perhaps surprising he may have been jaded, considering his big label record was as recent as 2021.

“The word jaded is an interesting word,” he ponders. “When I made my third record, I started working with outside people, new producers, because I needed to learn. It went well, it was so organic and holistic. Everybody was pulling together and the record did really well. It was a push forward into a new dimension for me; I was incorporating all these sounds. I felt like I was doing something that mattered.

“Then when we got to the end of a certain touring cycle, it was four albums made pretty tightly together, and two or three years of really intense work. I don’t know, I didn’t feel very complete as a person. And when my daughter Margot arrived, I wanted to take a step back.”

Turns out James’ instincts were correct, though he subsequently got drawn down a path that was not right for him.

“I started writing and working with other people a lot,” he explains. “Because it felt like an interesting thing for me to do. I wrote a couple of songs really quickly in that process, with the intention of them going to other people. So, I was out of my independent record deals. I would never really have kicked the tyres on a major label deal, but I took meetings because I wanted to see what they would be like.

“These two particular songs kept coming up in conversation. I was saying, ‘These are not for me, they are for other people’. The label said, ‘No, you’re an idiot, this is for you – we can make this absolutely sing for you.’ They pitched a vision and it’s more fool me for buying into it. But I wanted to believe it.”

The singer elaborates on the theme.

“My instinct is to try and do the fucking difficult thing,” he continues. “The difficult thing to me at that point was to go to a major label. The hubris of it all was to think I could bend them to my will, a ridiculous notion. But I’ve never felt I’ve had a musical problem, I’ve always had a PR problem.

“I never know how to pitch myself or place myself in the universe, because I’m not a very forward-facing person. So going to a major label and doing songs like that made sense. I thought, ‘They’ll figure this out for me.’”

James Vincent McMorrow. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

James Vincent McMorrow. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.LOST CONFIDENCE

James is deep in the memory of it now.

“So, a song called ‘Gone’ became the conversation,” he says. “Everything I did, they were like, ‘We really don’t mind how you spend the money we’re giving you, or what you do, as long as ‘Gone’ is the song.’ If you had told me 10 years previously, that one day I was going to get to go to LA with a bag of cash to do whatever I want, I would have told you I was going to Laurel Canyon to make a record that sounded like Jackson Browne.

“Instead, I was sat in this beautiful studio called Gold Diggers in East Hollywood, twiddling my thumbs. I had no idea what to do, because rather than critique what I was doing, the label insisted, ‘just keep ‘Gone’. So, there’s mistakes I made, there were mistakes the label made.

“It was less jaded, more hubris, more a lack of listening to the voice in my head. Because if I listened to the voice in my head, I would never have let it get within a million miles of me, because I knew it wasn’t a song for me. It was never supposed to be. I’ve always known when songs are for me, and when they’re for other people.”

James delves even deeper.

“I just lost my confidence and my sense of true north within it all,” he says. “So then obviously, the pandemic unfolds and everything is upside down. Then you have this record where there’s glimpses of me in it, and parts of it that I love, songs like ‘Headlights’. There’s lot of people I worked with on that record, relationships I forged that are so vital to me.

“People such as Paul Epworth, Lil Silva, Kenny Beats – these are good friends of mine now, people I make tonnes of work with, in other iterations. But I didn’t take the helm, I didn’t direct it. I didn’t guide it home, because I was putting too much stock in the label figuring it all out for me. So, by the time we got out of it in 2022, Grapefruit Season came out a year-and-a-half after it was supposed to.

“I made The Less I Knew as a mixtape to cleanse my soul, to get myself back on track and reclaim my confidence. Once I’d done that, doing Wide Open, Horses in this manner was the natural next step, to push myself back out into the world in a meaningful way again.”

Man, it’s time for a deep gulp of air. I applaud his thousand-foot view of the entire process.

“You have to accept failure,” McMorrow says simply. “To not accept failure is to learn very little from life. I’ll apportion blame, but I’ll apportion it to myself as well. When I talked about the label not really having any ideas, that’s more fool me for not knowing that was probably going to be the case. Ultimately, I could have forced their hand and I didn’t, because I was a little tired after the years of constant touring. I wanted somebody else to fucking do it for me.

“I went through some real dark moments after that. But once that clears out, you get a little clarity. You realise music is the thing that fixes the problems, so go make music.”

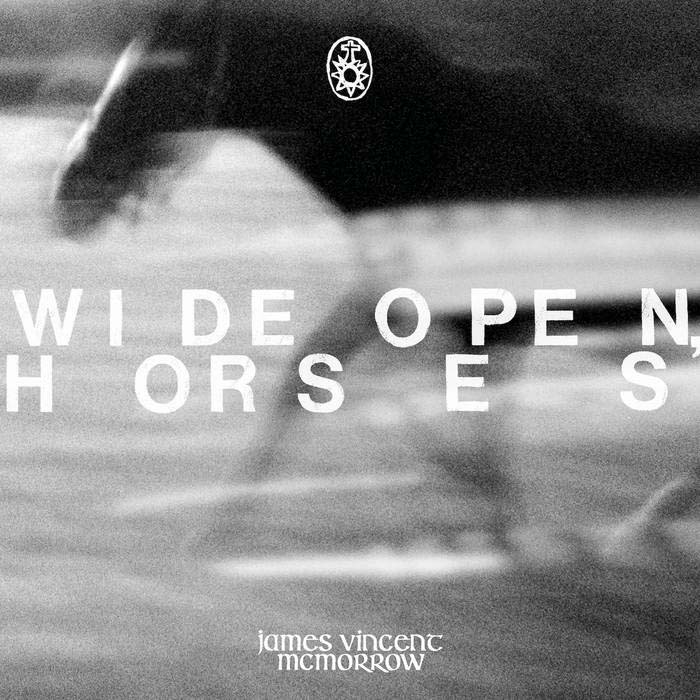

James Vincent McMorrow Wide Open, Horses.

James Vincent McMorrow Wide Open, Horses.TRUE VOICE

In promotional work for Wide Open, Horses, James has said that the process was rebuilding himself and his connection to music, and what he wanted when he was starting out at 20-years-old. What type of 20-year-old was he?

“I never went out,” he laughs. “I lived around the corner from Ró in Delorentos and watched that from a distance. I saw Director do their thing and was endlessly impressed by it all. I didn’t go to Whelan’s because I didn’t think I belonged. I didn’t put music on Myspace until around 2005. All I was doing at home was singing and writing, but I never finished a song. I took it really seriously – that if I’m going to finish a song, it has to be really good.

“I’m a deep appreciator of the Irish music scene,” he continues. “But I never engaged with it until the late 2000s. Derek Nally, who was the booker at Whelan’s, was the first person in the Irish scene that I ever gave music to. He was the first person that wasn’t my mom that liked my music. He really pushed me and helped me get gigs.

“It took me a minute to find a true voice, because early versions of me were very Laurel Canyon, very late ‘60s/early ‘70s American folk. It didn’t feel very true to me, in terms of my Irishness, my sort of lyrical voice. Actually, more my production aesthetic, because I grew up wanting to be Pharrell Williams, Timbaland. It was hip hop production and I wasn’t bringing that to bear.

“Hearing bands like The National and their different, really theatrical approach, or Sufjan Stevens and the way he arranges, I wanted to get to that point. But it took a while, I didn’t have the skillset, I spent three or four years building it. Once I was at a level where I was competent enough on all these instruments, I knew I could articulate a version I could stand over. That was a red line for me – I would never have put out anything couldn’t have stood over.”

McMorrow teases out the thought further.

“Sonically, it was compromised, but the songwriting wasn’t. The arrangements were interesting enough for me. A song like ‘We Don’t Eat’ could have been a Neil Young song and the early version of it was, but it just didn’t interest me. It was only when I found a syncopated piano line, with a steady kick drum, that I thought, ‘Okay, now I can build something my brain actually wants to hear.’ Yes, it might make it a little weirder, it might compromise its commercial reality, but it bears out.

“Time has been kind to those records. So it was worthwhile, and it put me on a path of longevity. We sold 200,000-plus copies of the first record, and we did it independently. But we just did it slowly and methodically, and that’s been to my long-term betterment.”

Following James landing those early gigs, he played in Europe and across America, selling his records. Back in Ireland, despite early champions such as Declan Forde at The Pod (“I would open every show at Crawdaddy”), things never really clicked, something he is now grateful for.

“It meant I became successful outside of Ireland before I became successful here. That meant when it did happen here, it felt balanced and part of a wider structure. But obviously, if you never have reflection points, you never really have a moment to rest. That was ultimately how I burned myself out around 2017. I kept finishing tours and thinking, ‘Alright, next one – we’ve got to go because we’ve got to build.

“Making grand statements with Post Tropical and We Move, and then making True Care, it felt like I needed to do these things, because we’d never had that grand moment. All those albums were really successful, but I didn’t take stock of it. I didn’t really appreciate it at the time, because it never really felt like I had those grand moments.”

Still, it’s a nuanced picture.

“If I’d had a gigantic radio song,” he continues, “everything else after that would have been a failure. So, for me, creative growth and a slow upward trajectory was exactly what needed to happen. Where it came off the rails was moving to major label, where all of a sudden, their expectations were so far beyond mine, anything I said felt really negative. Because I just wanted to keep going the way I was, and they were insisting, ‘No, if you’re not exponentially stepping up, that’s not worth our time.’ That makes you really doubt yourself.”

NEW WORLD OF POSSIBILITY

I think we’re now the last two at Hot Press HQ, which means we’re pretty late, so we best wrap up. In providing some further background to Wide Open, Horses, James nonchalantly informs me that Dan Auerbach of The Black Keys wanted to produce the record. Indeed, they worked together in Nashville on a track, ‘Darkest Day Of Winter’, which features on the album. But James eventually decided he needed to produce the record himself. I wonder about his process.

“I was building arrangements,” he explains. “I had a mic in my studio and everything was plugged into different amps. If I wanted to play piano or Mellotron through an old ‘60s amp, I’d just turn the amp up until the mic picked it up. I wouldn’t have headphones on, so every time I recorded something, all of the noise was filling up the spectrum. So it became really wild and unhinged sonically, and felt really fun.

“That’s how ‘Give Up’ happened, because I was doing this, and then Margo came in and started singing on the mics. But that wouldn’t have happened had I not allowed for it, and it opened up a whole new world of possibility for me. I wasn’t playing stuff for the band – they didn’t even know what they were supposed to be playing, because it was so muddy and messy. But the energy was there and all the songs were there. Once we were playing them, we’d finish the song, and we’d be like, ‘Wow, this is cool, this is working’. It felt very organic, I’ll never be able to recreate it. But fuck it, that was the point!”

On the eve of release of Wide Open, Horses, James is set to headline a Windmill Live Show, in the Townhall at 1WML, in the heart of Windmill QTR. The show is the latest in a series of lauded gigs, curated by Hot Press, that have featured major names like LYRA, Gavin James, Lisa Hannigan, The Coronas and. JVM’s gig will be followed with dates in the UK, Europe and North America. Is he match fit?

“Usually, I hate rehearsing,” he laughs. “Hate it. But our rehearsals were just so lovely. I don’t jam, and we jammed. We played a full band version of ‘Stay Cool’ for 20 minutes, with solos and noodling shit I would never ordinarily do. But actually it’s everything about what I should be doing. We will bring other people in for some of the shows, but it brings me back to when we did the shows for the second album. We were hanging on by the seat of our pants. It was so exhausting, but so fulfilling. Selfishly, I want that again.”

• Wide Open, Horses is out now.

RELATED

- Music

- 03 Nov 25

Album Review: Ronan Furlong, Elysium

- Music

- 28 Oct 25

Album Review: J Smith, I Stood There Naked…

RELATED

- Music

- 24 Oct 25

Album Review: ALKY, Rinse & Repeat

- Music

- 17 Oct 25

Album Review: Skullcrusher, And Your Song Is Like A Circle

- Music

- 17 Oct 25

Album Review: Tame Impala, Deadbeat

- Music

- 08 Oct 25

Album Review: Richard Ashcroft, Lovin' You

- Music

- 22 Aug 25

Album Review: Mac DeMarco, Guitar

- Music

- 24 Jun 25