- Music

- 10 Feb 25

Joan Baez: "I feel as though I found my people when I came to Ireland and the Troubles"

In Dublin for a screening of I Am A Noise, a powerful documentary on her life, folk icon Joan Baez discusses her first act of civil disobedience, Martin Luther King, guerilla recording in Hanoi, and the need for a universal protest anthem.

At the end of I Am A Noise, the rather stellar documentary about her sensational life, Joan Baez, earphones plugged into her phone, dances in the morning sun, in a desert landscape, alone with just her loyal dog. It’s a potent coda, one that represents the resoluteness, tremendous pluck and fierce mettle which the folk icon displayed repeatedly throughout her life, even when up against mammoth odds. I wonder what was the song she was dancing to?

“Almost always, believe it or not, I’m still dancing to the Gypsy Kings,” she laughs. “I keep telling myself, ‘You really should try another group’, and then I go right back to the Gypsy Kings. This morning in the hotel, I realised I hadn’t done any treadmill or walking, so I just danced for about half-an-hour.”

Talking with Joan Baez, hearing her distinctive Mid-Atlantic cadence, is to listen to one of the abiding voices of social justice and civil rights across six decades. I Am A Noise follows Baez on her 2018/19 Fare Thee Well Tour, culminating with her final ever concert at Madrid’s Teatro Real. It also – through diaries, audio recordings, home videos and drawings – delves painfully into her personal life.

The film takes the viewer to the edge of an awful trauma – indeed, the fact that the odious trauma remains somewhat blurred makes it all the more dreadful. The vile thing gravely deadened what should have been, and appeared to outsiders to be, a life at peace with itself. Her drawings, of what may be best described as her totemic animals, are utterly spellbinding, containing as they do nightmares manifesting from her subconscious. She says, “When you are trying to keep the truth in, it comes to you in nightmares and fits of fear.”

James Baldwin and Joan Baez, Selma 1965

Baez led a life less ordinary. Possessed with a voice that CNN anchor Christine Amanpour once described as “One of the purest notes in music history”, and armed with an intrinsic sense of justice that appeared innate, she battled inequality wherever she witnessed it.

“When I was 15,” she explains, “I had my first civil disobedience. Our school had an air raid drill. The siren would go off, and the kids would all run home and get in their swimming pools or whatever. It had nothing to do with any kind of reality. So I asked my dad, who was a physicist, how long would it take a missile to get from Moscow to Palo Alto High School? And it became very clear to me that the whole set-up was a joke.

“I mean, there was no way we would survive that kind of a bomb or missile. So the alarm went off and everybody left, except myself – I stayed in class. I was kind of scared, but I think that’s when I really learned that you do it, whether you’re scared or not.”

That strain of guts took her to the head of the anti-Vietnam War movement, of which she says, “I was the right voice at the right time – it shot me into another whole stratosphere.” An iconic picture shows the 22-year-old Baez, acoustic strapped to her back, peeking down on a quarter-of-a-million people at the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington in 1963. Her performance that day of ‘We Shall Overcome’, the civil rights anthem penned by Pete Seeger and Guy Carawan, made her synonymous with the song.

“It was very hot,” Joan recalls. “I’d never seen that many people in my life, and I’d already been working with the civil rights movement, so I was acquainted with a lot of the folks on this side of the mic. But it always goes back to that amazing speech; I was crazy lucky to be there and to be singing.”

Joan Baez with Martin Luther King at a 1966 march to integrate schools in Mississippi

Of course, the speech she is referring to is Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have A Dream’, perhaps the most iconic speech ever delivered. When speaking about Dr. King, Baez refers to the man’s humour, something that is rarely mentioned.

“He was very, very funny,” she recalls. “I think he had to remain very prim and proper, because the press would have made a hash out of it. So, all his humour was kept for when he was not in the church, or at the pulpit or speaking publicly. He was funny, sweet and brave as hell.”

Humble as she is, it must be pointed out that the Baez who arrived at the March on Washington in 1963, was a national sensation. The previous November, she had appeared on the cover of Time. Referred to in the media as the Barefoot Madonna, she describes the period as “going from feeling inadequate to being called the Virgin Mary”.

When I suggest that she found her people in the counterculture movement, she deadpans, not unkindly, “Yeah, I found some of them”, before laughing and elaborating.

“Seriously, I feel as though I found my people when I came to Ireland and the Troubles,” she says. “I found my people in Sarajevo in the middle of their war and in Hanoi in 1972. Because I’m happiest when I’m deeply involved in activism, non-violence and singing at the same time.”

In 1976, Baez attended peace marches in Belfast, London and Drogheda, organised by Mairead Corrigan and Betty Williams, who established the Peace People Movement and went on to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1976. Elsewhere, the eponymous track on Baez’s 1973 album, Where Are You Now, My Son? – made during a US bombing raid on Hanoi over Christmas 1972 – is a 20-minute epic of song and field recordings. It includes sounds of bombing, gunfire, air raid sirens and audio of a Christmas service, as well as conversations with Vietnamese and foreign citizens, who were secluded in a bomb shelter with Baez.

“Yes, it was incredible,” Joan explains. “It turned out that it was the heaviest bombing certainly in that war, and I think several wars. I didn’t know that at the time. All I knew that was that I came face to face with my mortality, looking at a hospital that had been bombed the night before. I was literally seeing parts of people around. So how do you not deal with your own mortality at that point?”

I suggest that less music nowadays is associated with political protest. Could a song like that be written today?

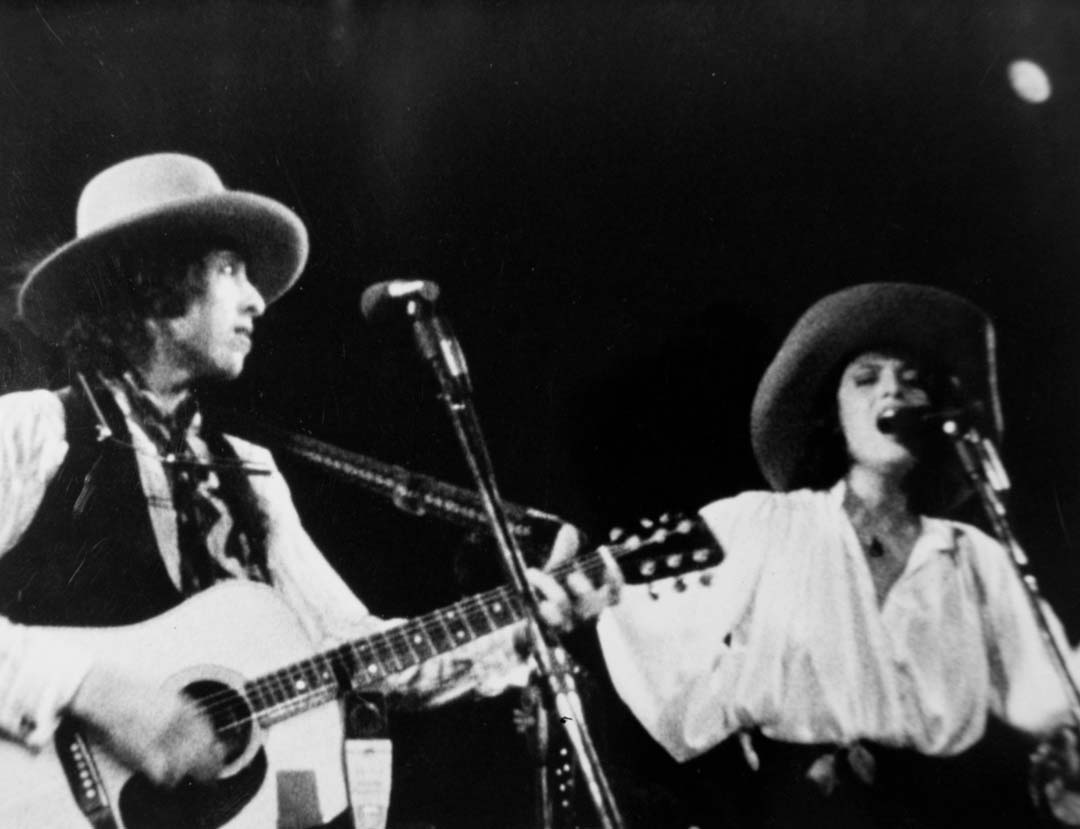

Joan Baez and Bob Dylan

“The first thing that comes in my mind,” she replies, “is that 10-year period. There was Joni Mitchell, eventually The Rolling Stones, Joan Baez, Peter Paul and Mary, Bob Dylan – and that time won’t come again. It was particular and I don’t know why it happened, but those talents were just massive. Right now, to try and duplicate that isn’t going to work.

“But along the way, somebody’s going to write an anthem, which is what’s missing. And probably writing an anthem would be the most difficult thing to set out to do, because you’re trying to do something meaningful, and trying to get people to sing it. So, if somebody wants to write an anthem that it turns out we can all sing, that would be great.”

I Am A Noise is out now

RELATED

- Music

- 20 Dec 25

30 Best Folk Albums of 2025

- Music

- 26 Nov 25

Bob Dylan performs The Pogues' 'A Rainy Night in Soho' in Dublin

RELATED

- Music

- 25 Nov 25

Bob Dylan performs 'Lakes Of Pontchartrain' live in Killarney

- Music

- 24 Nov 25