- Opinion

- 11 Nov 21

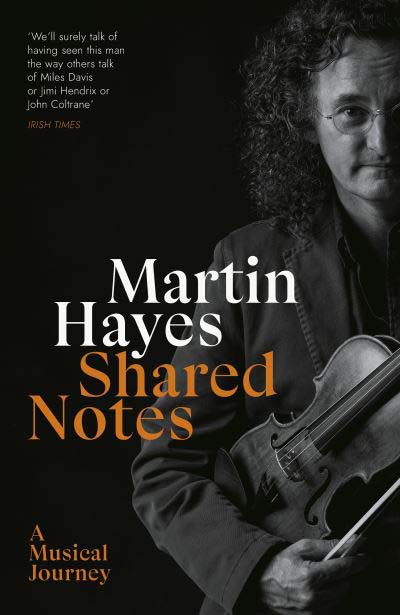

As he releases his autobiography, Shared Notes, Martin Hayes reflects on a remarkable journey – including playing and campaigning for Obama, smashing fiddles, and how he could have followed a very different career path into Fianna Fáil politics.

As one of the country’s most distinguished traditional musicians, Martin Hayes occupies an almost stately position within the public imagination. He’s an ambassador for our culture on the global stage, but also a fearless innovator – having played for presidents and dignitaries around the world, as well as performing alongside the likes of Paul Simon and Sting. That’s why the image of him smashing his fiddle over the head of a fellow musician in a Chicago pub on St Patrick’s Day – in front of a crowd of about 400 people – isn’t the easiest to grasp.

“It’s one of those moments that’s – literally and figuratively – a breaking point,” the renowned musician tells me now, with a smile. “It was the moment at which I pivoted. It was a wake-up call, and a moment to let me know that what I had been doing in my life up until that point was no longer sustainable.

“It was a shocking moment, having an outburst like that, and losing the rag in such a visible, crazy way – where I destroyed my own instrument that I had been carrying with me since I was 13,” he adds. “But it was a moment that I felt I couldn’t really cover up in the book. I had no desire whatsoever to tell this story, but I also felt that it would be somewhat dishonest if I glossed over it.”

Indeed, it’s tales like this that make Hayes’ newly published autobiography, Shared Notes, so captivating. But as he reveals, writing about his own life wasn’t something he’d “ever really planned on doing”.

“It just kind of evolved into that,” he says. “But I would say that writing about your family, your past, and your experiences is a therapeutic experience. I think everybody should do it, on some level. It’s surprising how much you remember. There are a lot of memories and some of them are very visceral.

Advertisement

“When I was writing the book, I was thinking, ‘I could write that in a paragraph, the whole thing!’ Because we summarise our lives. But when you start writing, the summary is just an invitation into the whole story – and then I was trying to stop the book from spinning out of control.”

The early parts of the memoir find Hayes reflecting on his childhood, which was spent soaking up traditional music on the family farm in Co. Clare. It’s a compelling portrait of a world that has, for the most part, disappeared.

“Up until the age 10, for me, was a world and a life that just suddenly went away,” he explains. “I was even aware at that stage, and I continued to be aware, that I’d actually grown up through something. I’d just seen the tail end of it. And I knew there would be a day in my life when I would be one of the few people who remember it. It’s a very separate reality from what we live now.”

During his early years, some of the country’s greatest traditional musicians would arrive at the family home, often unannounced, to visit his father, P.J. Hayes of the Tulla Céilí Band, and play tunes together in the kitchen. Among the visitors was legendary fiddler Tommy Potts, whose legacy has inspired the current generation of emerging traditional musicians – something Hayes has been pleasantly surprised to witness.

“The world we were in, musically, was quite obscure,” he smiles. “In some ways, time is a great leveller. Things that don’t seem important in 1972 begin to look more significant as time passes. Tommy Potts, who was a fiddle player that nobody listened to or paid any attention to, gradually grows in importance and significance, and becomes a bigger figure than he would have ever imagined himself.”

Politics was another great passion of the Hayes family. His father was an active member of the local Fianna Fáil party, and would receive Christmas cards from Éamon de Valera.

Advertisement

“Politics is largely about identity,” Hayes reflects. “One thing you would hear, campaigning in elections, is people in certain houses saying, ‘I am Fianna Fáil’ or ‘I am Fine Gael.’ I found that sentence very interesting: ‘I am.’ Not ‘I would prefer Fine Gael’ or ‘I think I like them’ – but to say that ‘I am’ is a very different political statement.

“If you watch politics all over the world, you still see it,” he continues. “They’re roping people into identities, like the Never Trumpers, the Insurrectionists, the Brexiteers… They’re herding people towards identity all the time. Small farmers in East Clare, of certain backgrounds, were herded into a political identity as well – and I grew up inside of that.

“Obviously, later on, I took a different view of that,” he adds. “But if I hadn’t taken another view of it, I could have ended up being a Fianna Fáil County Councillor, or a TD or something – and just simply perpetuate whatever it was, and fall into that, without even knowing why I landed there.”

After becoming disillusioned with Fianna Fáil as a young man, it wasn’t until 2008 that Hayes found himself becoming politically active once again – volunteering for Barack Obama’s campaign, and going door to door.

“Obama, for me, was a moment of saying, ‘Well, I actually believe in this – so I’ll support it,’” he tells me. “It was an important moment for me, to make a conscious political choice, as to who I was, and what I believed.

“So my political ideology fell left – or centre-left I suppose – at the end of the day,” he continues. “I’m somewhat of a centrist, in that I do believe that capitalism and business and free markets are also a part of every equation. We need a balance of all of these things. So moderation is a good political philosophy, as far as I’m concerned.”

Three years after campaigning for Obama, Hayes also got the chance to perform for the then-President of the United States.

Advertisement

“Wandering around the White House and the Capitol Building were kind of surreal experiences,” Hayes recalls, grinning. “And meeting him. Out of any of the presidents, meeting him was the most delightful one, because he was my favourite, and he was the one that I got involved with politically. Having that moment of being able to say, ‘You know, I volunteered in your campaign, by the way…’ That was fun.”

Of course, Hayes’ time in America wasn’t always so glamorous. When he first began living in the US as a younger man, he was working on construction sites in Chicago as an undocumented immigrant – an experience that has shaped the way he views the country to this day.

“America is a rough and tumble place,” he notes. “It’s very free and open, but they will let you collapse. There isn’t really much of a safety net there. When you crash there, you crash. But it’s also a place of tremendous opportunity.

“Obviously, at the moment, the political brinkmanship and the craziness there is frightening and disheartening. But within America there is still – hopefully – an openness to possibilities. And that’s important.”

In the book, Hayes reveals that relentless hard graft, pub gigs, and excessive drinking took a toll on him during these early years in the US. The aforementioned smashing of his fiddle was a rock bottom moment, and ultimately led to him giving up drinking.

“Traditional musicians were known to very often have problems with alcohol,” he reflects now. “It’s hard to measure the severity of those problems, but let’s put it this way – I drank a lot, and I partied a lot. I was out every night – not just some nights. In the end, it wasn’t really sustainable. It led to nowhere. So after that incident, I knew that I needed to get my act together. I knew I was going to have to sort my life out – push the restart button and start all over.

“There was a sense that I was at a moment of actual choice,” he adds. “I could save myself and make something out of my life, or I could just choose to waste it from that moment forward. Luckily enough, I woke up in time.”

Advertisement

From that crossroads moment, Shared Notes goes on to chronicle the starry heights Hayes has reached as a musician, including his work as a founding member of The Gloaming.

Credit: Heidi Solander

Credit: Heidi SolanderAt one point in the book, he remarks that making “the core” of traditional music “comprehensible to a wider world” has been a central part of his overall mission.

“There was a particular aspect of it that I wanted to have known,” he elaborates. “There was a kind of expression among those older great musicians like Tommy Potts, Tony MacMahon, and various other people. There was a message in their music that I thought was getting lost, so I had a mission to bring at least that part of it out into the world. I wanted their world and their sense of music to be known, to be understood, to be respected, and to be valued. I wanted that feeling and expression to actually be preserved, be protected, and be promulgated.”

Indeed, six years after The Gloaming became the first traditional Irish group to win the Choice Music Prize, the homegrown music scene has continued to produce a remarkable variety of artists drawing influence from the rawest roots of the genre.

“Every generation gets an opportunity to go, ‘Okay, let’s go right back to the start again and start all over,’” Hayes considers. “That’s an important part of any tradition. No tradition can exist as some kind of living artefact – it’s got to actually speak to now. When you hear it, it’s got to touch you, and reach you. It’s got to stay alive, and stay connected to its time, to its place, and to its people.

Advertisement

“So the challenge that arises in all of that, is how to genuinely keep what’s real, true and meaningful – and not lose that thread as you navigate these journeys into the future with the music.”

Towards the end of Shared Notes, Hayes also shares his reflections on religion – having become disillusioned with Catholicism throughout the course of his life. Spirituality, however, remains a crucial part of who he is, he tells me.

“I’m not irrational – I’m a logical, questioning, curious human being,” he explains. “I’m interested in lots of things. But spirituality is part of the mix of life. I think that there’s a mysterious, unknown, larger realm that’s a little bit beyond our grasp – and it sparks my curiosity quite a lot.

“I have faith in those things,” he adds. “ All religious viewpoints are acceptable to me. I don’t buy into institutions or organised religion – and the Catholic Church as an organisation has no appeal to me. But I’ll find, ‘This is an interesting way to think about this.’ Or, ‘This is another interesting way to think about that.’ That philosophic, spiritual view of life is a very close partner with the creative process. Entering into a creative process and engaging with spontaneous outcomes is a spiritual thing in itself.”

Although Hayes has, by his own admission, “too many” projects and collaborations in the pipeline, Shared Notes is hopefully not the last time his relationship with music will make it onto the page.

“Writing this book has given me the idea I could actually write,” he smiles. “Now, I don’t know if I write well enough to say that! But I enjoyed the experience, and there’s a lot more about music that I’d like to explore further – the nuts and bolts and the grit, and the philosophical side of it.”

• Shared Notes is out now, published by Transworld.

Advertisement