- Music

- 03 Mar 22

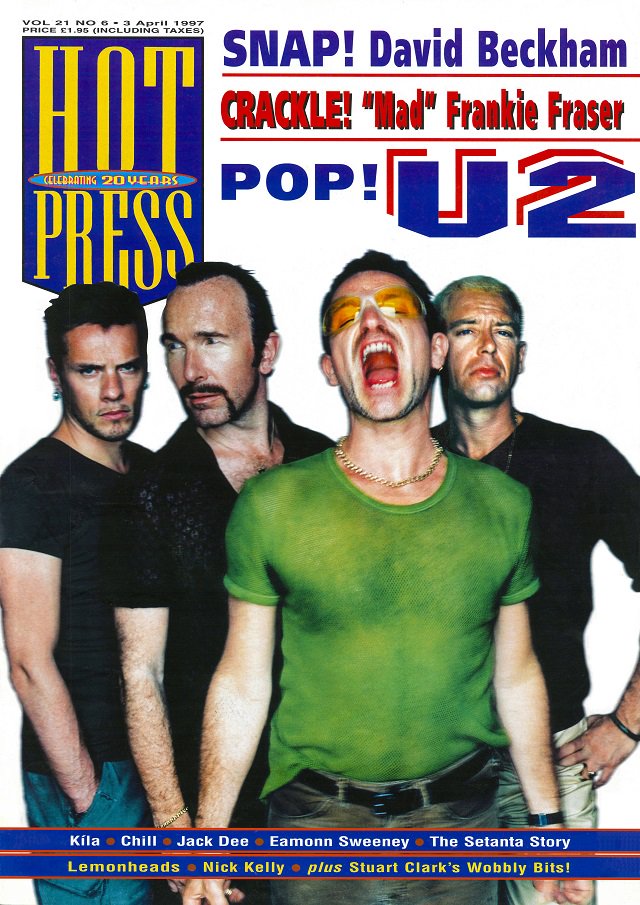

On this day 25 years ago: U2 released Pop

On this day 25 years ago, U2 released their ninth studio album, Pop. To mark the occasion, we're revisiting a classic interview – originally published in Hot Press in 1997...

The initial rumours were that it was going to be "a rock 'n' roll record." Then subsequent whispers hinted at everything from trip-hop to techno to ambient. But U2's ninth studio album, Pop, is all of these things and more. It's the first album since 1983 that they've made without the assistance of Brian Eno, it's been a long time in the making -- roughly a full year, all told -- and it's selling like the proverbial warm buns. Here, Niall Stokes talks to Bono and Adam Clayton, as well as co-producers Flood, Howie B. and the Edge, about its lengthy genesis and what the band hoped to accomplish in creating it.

Backstage at some celebrity charity bash, a plum-accented classical conductor is talking at Bono. "You're involved in a pop group," he says, one eyebrow arched like an accusation.

It isn't what he says, it's the way that he says it. There's a pause and then it comes out like...pop group. His contempt for the very thought of it is palpable. A lower form: pop music.

The encounter plays on Bono's mind. The condescension rankles. Who the fuck do these guys think they are, talking down to the practitioners of such a noble calling? The implicit assumption seems to be that there's something unworthy, something unclean -- something to be ashamed of! -- in being in a rock 'n' roll band. In a successful rock 'n' roll band.

Pop music. A term of abuse.

It crystallises something for the U2 singer. Pop. Your man thinks it's an insult. Well, fuck him. It's time to re-appropriate the word. Turn it into a badge of honour. What do you do? "I'm a member of a pop group." What sort of music do you play?

"Pop music."

Forget dance. Forget rock. Forget rap. Forget hip-hop. Forget trip-fucking-hop. Forget the blues. Genres are for people who are happy to accept that what they're doing will appeal to fans of a particular genre. But when you're in one of the biggest bands in the world, genres are like boxes -- too constricting. When you're in U2, you gotta see the big picture.

Pop music. The picture doesn't come any bigger or wider than that. From Frank Sinatra through Elvis, the Beatles and Bob Dylan to...Oasis. Nothing wrong with that shit.

No more apologies.

"During the '80s, it was almost as if we had to say sorry for being in a big band," Bono said to me, somewhere in the middle of recording U2's official follow-up toZooropa.

"That whole indie thing is such a con. We were supposed to feel guilty about the fact that we'd been successful. But that was what we wanted, right from the start: to be one of the biggest bands in the world."

The band were in the middle of recording a song called "Gone" at the time. Bono described it as a defiant gesture, a fuck-you to the begrudgers. It was about being in a successful band and enjoying it. That spirit was in the air -- and it sparked a potential title for the new record.

U2 had begun recording with the idea that they were going to make a real rock 'n' roll record. Working with Nellie Hooper, the rumour-mill said they'd gone trip-hop. The news that Howie B. was on board surfaced and the focus shifted to dance. But there was one word that would allow them to explore all of these areas at once and not have to think twice.

In the end, you can interpret the choice as defiant or ironic -- or simply as a statement of fact. But it's not a bad title for an album destined to chart at No.1 in 14 territories around the world in the week of its release. Not a bad title at all.

Pop.

So let's talk about -- pop music...

From the outside, it may seem inauspicious, but U2's studio and band HQ is a beautifully appointed oasis, close to the dockland area of Dublin. Despite its city-centre location, the atmosphere on a sunny spring or summer's day is almost balmy. The studio overlooks the picturesque Grand Canal basin, and with the windows open, the lapping of the water in the background provides a soothing undercurrent to the babble of conversation in the studio's green room, where people hang out between takes, read or conduct occasional interviews.

Upstairs, there's food and coffee constantly on the go, under the watchful, guiding hand of the band's favoured chef-in-residence, Aonghus Hanley of Tosca. The ambience is warm and convivial -- the kind of place in which you instinctively feel it would be a pleasure to work.

I was in and out of the building, researching Into the Heart - The Stories Behind the Songs of U2, during the early stages of the recording of Pop, and it seemed like a happy camp. Listening at the time to black tales of darkness and rancour from the Berlin sessions which the band had undertaken for Achtung Baby, the mood seemed all the more positive and relaxed by comparison. But there was never any doubt about the scale of U2's ambition for the work-in-progress.

Like Rattle and Hum, the Zooropa album had been a transitional one, put together on the run while the band were still locked into Zoo TV touring commitments -- and finished, of necessity, within a relatively tight time-scale.

Some superb tracks notwithstanding, The Passengers' Original Soundtracks 1 -- the band's ultimate collaboration with Brian Eno, which followed Zooropa -- was an even less driven artifact and one which everyone involved recognised in advance as an exploratory, left-field exercise.

In contrast, the next outing would have to be the full-on, flat-out, totally-focused, thoroughly-planned real U2 deal, in a line from The Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby. It would have to be a big one -- a record which would at once vindicate and celebrate the band's status as one of the major rock 'n' roll acts on planet earth. Oh, and they had other ambitions for it too!

Examining what was happening in rock 'n' roll in the mid-'90s, it became clear that just about everything was up for grabs. Dance music and club culture had produced a kind of fragmentation, undermining to an extent established forms of live music and in the process defining the taste -- not to mention the attitude -- of a less easily connectable new generation of record-buyers. Oasis, meanwhile, had struck a blow for pop songwriting, potentially leaving the more self-conscious practitioners of "serious" rock music in a dangerous vacuum. You could tell that U2 were determined not to find themselves among the casualties of music's shifting gestalt.

"You have to keep in touch with what's going on at the cutting edge of youth culture and of contemporary music," Adam Clayton suggested early on in the recording ofPop, and it was as accurate a statement of intent as you could possibly expect in the circumstances.

Having flirted with a more rhythm-oriented sound in the course of the Passengers experiment, Edge was thinking along similar lines. "On the next record we're going to be pushing even further in the direction of allowing some of the aesthetics of dance into our songwriting," he revealed early last summer. "Structurally-speaking, dance music is probably the most experimental music right now. Albums like the Underworld album and the Chemical Brothers' are really interesting -- a lot more interesting than Brit-pop. A lot of that's very retro. With Oasis it doesn't matter because the vibe is so strong, and the songs are so strong, that they could probably play them on tin whistles and still blow your socks off. But a lot of the other stuff is almost as bad for me as grunge, in the sense that it's not pushing forward. But these dance music forms -- they're experimental and innovative -- they're for real."

To people who still associated U2 with the messianic desire to change the world which had been evident to different degrees in their music on War, The Unforgettable Fire, The Joshua Tree and Rattle and Hum -- but also in their support for Amnesty International, Greenpeace and War Child, and the links they made with Sarajevo during the Zoo TV tour -- this might have sounded like insidious stuff. Dance music, after all, goes hand-in-hand with decadence -- with drugs, hedonism and sex -- and this, surely, is not what U2 are supposed to be about.

"I think some people thought we were just too stupid to enjoy our success," Edge acknowledged, "too serious, too po-faced, to enjoy that fact that we were a huge rock 'n' roll band. You know: 'what a fucking waste, you being a huge band. You're not into drugs, you're not into sex.' It was...'God, what a travesty.'

"I'm not saying that we've now turned into drug-crazed lunatics, but what happened was that we decided quite consciously that we were at a certain point where it was probably rigorous to keep our anti-glamour stance -- but also boring, and not as much fun as allowing that in. So we started to hang around in these glamorous circles and started to write about it. We don't take it seriously though. If you get into it, that's the rule you have to understand."

And so dance culture became part of the smorgasbord, personified in the mercurial, wicked presence of musician, DJ, mixer and producer Howie B in the Pop recording team. Steve Osborne was part of the plot too, and Spike, who was doing a bit of work with the Spice Girls on the side at the time. But the man at the production helm, the head honcho, was Flood (a.k.a. Flood), who'd worked with the band previously, most notably on Achtung Baby (as engineer) and Zooropa (as producer).

They made a good team, the whole wild bunch of them sharing an abode out in Sandycove for the duration and getting on like a house on fire -- well, most of the time. It was Flood's job to wake the rest of 'em up, between 10:30 and 10:45; for Howie that part was a pain in the ass. Then they'd trundle into work together, to start before noon.

"Flood used to waken Spike and myself up," Howie recalls. "I used to hear his door open and it'd be 'Ah for fuck's sake' (groans). I'd hear him walk down the stairs and I'd go 'I've been up for ages' -- which, of course, I hadn't. I had a plan to wake Flood up myself one day, but I never actually managed that. It's a shame. I would've put him into shock if I'd managed it."

Both describe the atmosphere in the studio as positive and energetic. You get the impression that a genuine sense of community permeated the sessions.

"It was good," Flood recalls. "Generally it was very intense, but I don't mean intense in a down or negative kind of way. You know, one minute we'd be rolling around having a laugh, then the next we'd all be very concentrated trying to work out how we'd make sense of a particular song."

Usually, the team would work until 2 a.m. or 3 a.m. the following morning -- though there was time along the way for a spot of anarchy.

"You wouldn't call it a party atmosphere, but there was definitely a good vibe going on in the studio," Howie explains. "Occasionally, we'd be set adrift on cookery lessons, which was really exciting. Aonghus, the chef, introduced us to some culinary delights -- mystical delights, I would call them -- so it wasn't all strictly business. Not at all.

"There was this sausage that he used to make which had this funny ingredient in it -- licorice or something. The famous licorice sausage! I've never tasted anything like it anywhere else in the world. It actually tasted OK. So there were loads of surreal little things like that happening, just to swerve your attention away from what you were doing. It was good though -- 'cos sometimes by doing things like that, it actually brings you back to what you really should be doing."

On Thursday nights, the crew would end up in the Kitchen and party until late. But even then the brainstorming wouldn't come to a full stop.

"You'd work on a tune all day and then you'd go home or go to a pub or a club or something," Howie elaborates. "But the tune doesn't leave you, it's going 'round in your head, so you could have an idea then or you'd talk about it and where it was going to go. The brainstorming could happen anywhere. You could even be in bed and have an idea. The problem was remembering it."

The band had set themselves a summer deadline to have the album finished. By late spring, it had become clear that things weren't progressing swiftly enough. In their own minds they hadn't yet established a location for the record; they had no sense of what would give the album the continuity of feel that they'd always sought in the past.

Not a lot of Achtung Baby was actually recorded in Berlin, but the dark and brooding atmosphere of the place permeates the record. Similarly, they located Zooropa in an imaginary city in the future, and the songs reflect a sense of dislocation that crystallises within that frame. Never mind a title, Pop hadn't yet found itself a home.

The band thought about Cuba and were tempted, but the cynicism they'd almost certainly have been confronted with as a result dissuaded them. Instead they upped camp and split for Miami en masse.

"We thought Miami might be an interesting spot," Bono concedes. "We got excited about it because it's a cross-roads. It has a glamorous side. It has a humorous side. And then it has religion down there, which is amazing. It's a real melting-pot. But it just wasn't enough. In the end, there's no one location. I think it's deeper than that."

Had it any location from a bass player's perspective?

"Everybody's kitchen at 2 o'clock in the morning!" Adam laughs. "No, I don't think so. Essentially I think it's the world we live in. I mean it is Dublin, some of it. It is Miami. It is New York. It is London. All that's in there. And an evening in Paris, somewhere along the line!"

"To me the songs feel like conversations," Bono adds, searching for an entree that might be useful in attempting to understand the album's modus operandi. "Overheard conversations. Or conversations you're having with yourself. It's like a movie that opens in the middle of a scene. You're brought immediately into the action and there's lots of little arguments going on. It's like being in a band really (laughs). But I don't think it's got any physical location."

It may not have provided them with the hook they'd been hoping for, but their Miami sojourn proved useful all the same. So what happened, that it all went so horribly wrong?

"I'm probably the only one who can remember," Adam laughs. "We'd been in the studio for a while, slugging it out with the direction of the record. And it's a very nice place to be stuck for six months or so -- but I think at that stage we all needed a bit of fresh air. So we went to Miami and we had a very good time!

"We went out. We met a lot of very serious people and some very superficial people and enjoyed both. We were introduced to the art of smoking cigars. We went to this kind of Mafia, late-night place -- none of your old spit 'n' sawdust here, this was shag-pile carpet all the way. And generally we had a good time. We came, we saw, we conquered. It's in the lyric. It was all there and our eyes were wide open. Some of the time."

Did anyone get sick?

Bono: "On the shag pile? No, vomit was kept for the microphone. We didn't get that much work done, but we had a great time and we got a tune out of it. But it's a mad place. In Miami the hoods have all seen Scarface and they're sort of art-directed."

So can you explain the reference to surgery in the actual song, "Miami"?

"Everyone has a new face there," Bono says nonchalantly,

But it comes up again in "The Playboy Mansion." Is this becoming a bit of an obsession?

"That's the thing about plastic surgery," Adam responds. "You start with the nose and pretty soon you're into big money (laughs). I heard a story about this rich lady recently, who decided she was going to look after her hairdresser, who was a young girl, by paying for her to have a new nose. So the girl goes off and she has the new nose and she comes back and the woman says: 'Darling, I think now we've done the nose, we need to do a bit to the eyes.' The thing about plastic surgery is once you start, where do you stop? I think that's what happened to Michael Jackson."

It's no coincidence that he gets a mention in "The Playboy Mansion," then?

"I think surgery with Michael Jackson might have something to do with editing," Bono theorises. "If you're in the studio and you're in control of what you hear -- you can up the bass, down the snare, you know, 'louder, boys, less horns' -- I think Michael Jackson started to do that to himself in some way. It's the critical eye that makes him such a genius being turned on himself -- the knife turned around. I suspect that's where that came from. And he was such a beautiful-looking boy. That's the sad thing."

While we're still in our Hawaiian shirts, what's behind the "Miami, my mammy" line? Are we talking about a serious Oedipal complex here?

Bono: "Al Jolson was down there! I dunno, it's just the humour of it. That's one bad mother, Miami (laughs). I could have said Miami, my granny, but I don't think it would've had the same force, somehow! Or 'nanny' would've done.

"It wasn't what I intended, but the lyrics were written quite quickly in the end. I intended to make it more of a record about words but the way things panned out they weren't overworked and that's what's fresh about it. They're not thought-out yet, but you know when a picture's finished. It isn't what you've painted -- you just know that it's right, that it expresses something. You know there's an honesty to it.

"Songwriting is more like painting than people think. Pictures, feelings in your head -- you're instinctively led to them. You intellectually check yourself but you're led by instincts first. And they're not necessarily autobiographical. You've got an arm of one person and the leg of another. In a way, that's what makes them hard to talk about."

But talk about them you must.

It would take more than the abracadabra of a three-week working holiday in Miami to define the soul of Pop. It would take something much more fundamental: good old-fashioned hard graft.

Whatever possibility existed of the record becoming the ultimate shiny, happy superstar celebration of the joys of life lived in the ether evaporated anyway, literally as the band were planning their return flights from the land of Disney. They flew back from Miami in May to attend the funeral of Bill Graham, a man who had been pivotal to their career in crucial ways in the early days, and who had continued to write about them with supreme insight in Hot Press. The news of Bill's death, from a heart attack, had come as a fierce shock to the system.

The mood in the camp changed, Flood says. No one might have been able to articulate precisely how it affected the end result but the evidence is there in "Gone." What Bono had been talking about in March as a two-fingered salute to the self-styled guardians of rock's ideological moral high ground, and a dismissal of the indie ethic that sees something inherently suspect in a band that's successful, was transformed into something else entirely: a meditation on the superficiality and transience of success itself, over which the spectre of death hovers like a stark premonition.

"Closer to you every day," Bono sings. "I didn't want it that much anyway," and the echo is unmistakably of the hymn "Nearer My God to Thee." Nor is that uncharacteristic of the record as a whole. With "Discotheque," the album may open with what appears to be an anthem to the pleasures of the moment but there's a river of darkness running through Pop that comes close to despair at times.

There had been talk of finishing recording in July, with an autumn release in mind. By mid-summer a huge amount had been achieved but everyone became aware that the project wasn't going to run according to schedule.

"We'd reached a lot of goals on conception but actually bringing them to fruition was proving extremely difficult," Flood recounts. "At the time it was really deflating, a real let-down not to achieve what we set out to achieve and so we just took some time off. In hindsight it was good because everybody really needed the break to clear their heads. But it didn't feel that way at the time."

The projected release date was pushed back to November. A second crunch point arrived when it came to put up or shut up time in relation to that deadline. Larry Mullen's dictum -- it'll be finished when it's finished -- began to make real sense. But the stakes were becoming higher all the time, with tour dates to announce and concert tickets ready to go on sale.

"It was pretty serious when the band had to tell Paul (McGuinness) that they were not going to make their first deadline," Howie reflects. "It was a big thing. I suppose I didn't realise how big until I saw the number of schedules that had to be pushed back."

In some ways the second critical decision -- that there wouldn't be a pre-Christmas release -- was less damaging to morale. "It was a hard decision to make but we weren't so down as a result," Flood adds. "In a weird way it just spurred us on, into the last 5%. Because the only premise for extending the deadline arose from the question: did we think that, as a body of work, this was finished to the best of our abilities, and in the way that the band wanted themselves to be perceived? We felt at that moment in time that it wasn't -- and so the second delay was like a hard slap of reality in the face."

The roadblocks had to do with the normal shit: having put down 35 backing tracks, there were too many skeletons of songs to choose from and a degree of uncertainty about which ones to focus on. And inevitably, Bono and Edge (there were two suckers to blame on this occasion!) were still procrastinating over the lyrics. But there was something else going on too.

No matter how important it was to know what was going on at the cutting edge of youth culture; no matter how committed the band were to embracing the sonic possibilities of techno, trip-hop or DJ culture, their conscience would have to be clear that first and foremost this was a U2 record.

"This is something we're finding out again, working on the live set for the tour," Bono acknowledges. "You know, you can write a tune in any style but when you bring it back to the band it takes on a new life. I guess we always knew this, but in the end what happens is that when we play together -- as they say in New Orleans, some other kind of shit happens. So that's what we found on this whole album. Things would go into one area, what you could call a genre, and we'd have to pull them back out. We'd find out that the band version would, in the end, be more interesting than anything we'd produced along the way."

You could call it the Larry Mullen test -- if it passes, it's a U2 track, but if it doesn't, can it. In this instance, the drummer had a particular ally in Flood, who saw the rhythm section as being crucial -- with the result that Adam Clayton and Larry together turn in the performance of a lifetime.

"I think maybe we have got better," Adam says disarmingly. "But this time around the rhythm section certainly got more attention. In the past, as a producer, Brian (Eno) felt a need to push tracks through, and that forced the pace, but Flood was very conscious of making a band record, one where the songs would work primarily between the four of us."

Sometimes it's necessary to go the long way 'round to get from A to B -- especially if you're unsure in the first instance precisely where B is.

"A lot of the tracks were experimented with in terms of dance," Flood observes, "and really one of the reasons why things took as long as they did is that there were various ideas for the treatment of a song -- so we'd move each one through different areas, and experiment with it, and then sometimes find that the original idea was the better one. But when you go through this process, there are things you can draw from the second approach and sometimes even the third approach.

"At the end of the day, though, it's more of a rock 'n' roll album even though it's called Pop. It's like a giant melting pot of different styles. Different things are pushed to the fore on different tracks but ultimately it's something new -- and yet something that's still very much U2."

You can say that again. Over a year after embarking on the first demo sessions for the record, with the guillotine about to fall on a third and final deadline, the band were still high-wiring it. Howie B had been arguing with Bono about the lyrics of "Miami," with the result that the final verse was only written and recorded while the track was being mixed.

Worse was to come. Having high-tailed it to New York to master the album, Bono decided that he wanted a new intro to "Discotheque" -- in effect a new intro to the whole album.

"It was outrageous," Howie says. "It had gotten to the stage where I couldn't speak, I was that ill. I was run down, my chest was caving in, everything was caving in. It was Saoirse's birthday and she was in New York as well and I had to meet her and then at about 10:30 Bono turns around and goes 'listen, it'd be magic if you could get a new intro together for "Discotheque".' And it was just like...(groans)

"I got into a cab, went up the road to the Hit Factory. I was kicking things like you wouldn't believe, going 'Fuck! Fuck!' Like, we were in the middle of mastering an album and they wanted to change the intro! It was like, 'any ideas?' And swirl was the idea. That was what they came up with, a 'swirl' sound. For fuck's sake!"

Howie had a bash, thought he'd cracked it, phoned Flood at Master Disc and played it down the phone to him. Flood said nothing and Howie got the message. Fuck! Fuck! Fuck! He threw down the phone, turned up the speakers, pushed all the faders up -- and BAM! Blew the fuck out of them: two $30,000 speakers gone.

"After I'd got all that aggression out of me, I got what is now the intro to 'Discotheque' about ten minutes later. So I phoned them up and I went 'come on 'round, ye fuckers, I'm ready.' So they all trooped around and I couldn't play it to them properly 'cos I'd blown the fucking speakers! I'm still annoyed about that evening -- but I got a good piece of work out of it anyway."

A good piece of work. It isn't all that counts, but it counts for a hell of a lot -- and the overwhelming critical consensus is that U2 have delivered that and more with Pop.

"I don't think we could face having made a crap record," Bono says. "I think it would destroy the group. I don't think we've made one yet but it gets harder and harder to better yourself. We can't stop -- so I guess there's gonna come a time when it starts going down the other side."

All the familiar intensity is there in his voice, the appetite for the fray that has characterised U2 from the beginning. He's ready for the shuffle, ready for the deal, ready to let go of the steering wheel -- he's ready, ready for what's next!

"That's the time to stop," he says passionately. "When it starts going down the other side. But that's not happening right now, that's for sure. We're getting the best reviews of our whole life, and from the most miserable of quarters. And generally, big groups just don't get those reviews because people don't want to give you the cream on the cake. They're wrong to think like that because they should forget about your stature and context and think about the quality of the work. But in this instance, I think we're coming out on top, because the reviews are unbelievable."

And the final nail-biting climax notwithstanding, it was achieved without the same internal conflicts and blowouts which had characterised the band's more intense albums in the past.

"It's been described as a man's record," Adam reflects, "and I think that's appropriate in that things are not quite as extreme as they were and you actually get to like a bit of moderation! It was a great record to work on. It was hard. It was very hard at times. But it's pretty good, having done this for 20 years with your three best friends and still to be able to come up with the goods."

You can tell that Adam has become stronger over the past two years, that he went to the edge and flirted with disaster in the past but that there's a new stability and confidence in his life -- and his work.

"I'm very proud of the record," he says. "I'm very proud of everyone's involvement and commitment. We may be at the top of the pyramid, but Flood, Howie, Steve Osborne, Spike, Rob, Nellie's contribution and the members of the crew and everyone involved in this are all important -- and I can look back over all that now and say 'Didn't we do well!' What can you say? It sounds over the top but it's not a bad position to be sitting in. And I love my dog (laughs."

It's possible to say that, precisely because U2 refuse to rest on their laurels. Every time they set off on a new voyage, it's a blank page. Then they get scrawling.

"I was reading a book on Jack Kerouac and was reading about him smoking a bag of grass and praying, literally, for a vision of a language or a way of writing that would be both precious and trashy," Bono says. "That's what I'm aiming for. What I would like to do as a writer is to be able to mix it all up..."

To express the fact that there's a bit of a wretch in you alongside your idealism...

"I think I've got closer to it than ever on this record. And it's great to be able to get away with it. We can write sexy songs and spiritual songs -- and songs that are both. We can write anything we want -- and get away with it. This is the place we've made for ourselves after 15 years of making albums."

And with that he smiles a beatific smile.

Can't blame him, either. It's not such a bad gig being in a pop group, after all.

That's a...pop group.

Browse the extensive Hot Press U2 Collection here.

RELATED

- Music

- 05 Jan 26

50 years ago today: Bob Dylan released Desire

- Music

- 15 Dec 25

Adebisi Shank release special Christmas mixtape

- Music

- 11 Dec 25

21 Savage announces new album

- Music

- 09 Dec 25