- Music

- 30 Apr 24

On April 30, 1994, Riverdance debuted during the interval of the Eurovision Song Contest – which was being held that year at the Point Theatre, Dublin. From that seven-minute version, a phenomenally successful stage show was developed – which continues to be performed around the world. To mark the occasion, we're revisiting composer Bill Whelan's reflections on the origins of Riverdance...

An extract from an interview with Bill Whelan – originally published in Hot Press in 2014:

Bill Whelan’s career had been going well. He was up there among the go-to guys in Ireland, composing and arranging for theatre, film, TV, radio and orchestra, as well as working as a record producer. As far back as 1981, he had written ‘Timedance’ with Donal Lunny for the Eurovision interval. Now, another Eurovision-related opportunity presented itself.

“The idea to do something as the centrepiece of Eurovision was Moya Doherty’s,” he says. “Her job was to deliver the 1994 Eurovision Song Contest and she needed a piece for the interval. She had seen a number of things that I had done previously like The Seville Suite and particularly The Spirit of Mayo, which was done in 1993. Both Michael Flatley and Jean Butler had been in the Spirit of Mayo concert, and she had seen both of them and she said they looked amazing and the way Michael was presenting his Irish dance looked like something we could tap into. And Jean Butler was so beautiful and such a beautiful Irish dancer. And so Moya said she wanted to do something that would really present Irish dance in a theatrical way that hadn’t been done before.

“We had a very memorable meeting in a small café on Baggot Street. She said look, I’d use a lots of drummers as in the Spirit of Mayo – something with that power of drummers. And we are using the motif of the Liffey – because the Eurovision was taking place on the Liffey. So she said: think about it and see what you come up with.

“I went away to think about what could be written in that vein and that started the process. Then she brought in Michael Flatley and Jean Butler, and I began to play them what I had written for them, and we talked about how we would structure it. I basically took the life of the river as the motif and started it with Anúna, who I had worked with in the Spirit of Mayo, and I wrote the lyrics for their piece, and then Jean Butler’s piece and then the two of them coming together – and then the big finale. And the structure was to have the shape of a river: it starts small, and then it builds and builds, and then goes and rushes out to the sea.

Advertisement

“That’s what was driving the original conception I had – and that’s what it became. Mavis Ascott did the choreography: she’s a very good stage choreographer who is often not spoken of and who would have been responsible for the big line of dancers. Michael Flatley created the steps for himself, and Jean and himself did their pieces together. So that’s how the original seven-minute piece evolved.”

The story of what happened next is fascinating: the truth is that it all could so easily have run aground, had it not been for Bill Whelan’s persistence.

“I felt that we had really something, and I didn’t know what it was. In our business, you just don’t know if something is going to take off. But I did feel there was something special about this, and so I went around the record industry. And I said I’m doing this piece of music for the Eurovision,and I’d like to make a record of it, but I have no money. Well, I couldn’t get the money to do it from record companies. RTÉ weren’t interested in being involved either.

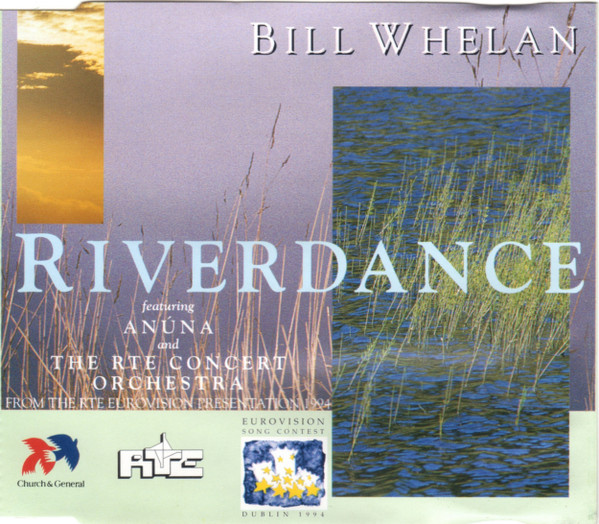

“So I eventually went to the Church and General, and I spoke to them, and I found myself in this extraordinary situation of sending my demo over to an insurance company. And I got a call in the afternoon. It was this guy Damian O’Neill. He said ‘yeah, we had a listen to that, it’s pretty good’. He asked what do you need to do this? I said I need ten thousand pounds, which at the time was a lot of money, to pay for the orchestra, the recording, the pressing. He said ‘we’ll give you that’.

“I suddenly had the capacity to make the record. And we went into the studio, and we recorded the track. I eventually went to Paul McGuinness, and we got Son Records, which was part of Mother, which was U2’s label, to release it. So it came out on U2’s label, and it was ready and in the shops the day after Eurovision. And a week or so later, it was No.1.

“So through a mixture of the creative work and a little bit of entrepreneurial spirit, we had a record – and now we had continuity. It wasn’t just something happening on the night of Eurovision and everyone thinking, ‘What was that?’ Now we had a record – and it was played everywhere: first in Ireland, then the UK – and then everywhere else.”

Advertisement

The euphoria after the Eurovision was extraordinary. Almost everyone in Ireland seemed to sense that this was a unique moment. All the old inhibitions surrounding Irish dancing – and Irish culture – had been swept away. A triumphant piece of orchestral music that was based on the tradition had created a context that made Irish dancing sexy. The music shot to the top of the charts. The question now was: where to from here?

“We were very excited by what had happened. Moya, and I sat down and talked about doing a show – that there was obviously an audience for this and a demand for more. And we talked about what it would be and I said I was very comfortable working within the some of the genres I had already approached: eastern European music, that I had done on East Wind with Andy Irvine; Spanish music, which I had done in The Seville Suite; and of course Irish music.

“If we could stay within that, then we could do Riverdance – and turn the river’s story into the circular journey of a nation: the river going out to the sea and coming back as rain and nourishing the river again would symbolise the nation going out to foreign parts and coming back and nourishing the homeland again. And I said: we could make a show about that.

“That became the template. And then I sat down and wrote four pages of A4 on what each dance piece in the show would be about. And then, at the end of October of 1994, after Eurovision, I sat down to write those pieces to the template that I had created. And that became Riverdance, the show.

“All of that music, in both cases, was down on paper, before a foot was put on the floor of dance – and everything that was done eventually and spectacularly in the dance was informed by what had happened in the music. So for me, Riverdance was a very personal creation. There were involvements with the director John McColgan and obviously Michael Flatley wanted to do a piece of just solo dancing, which he did. But Riverdance was on those four pages of A4 – and that was it. We might have changed it a bit over the years – pulled a piece out, put in another piece. But broadly that’s still the shape of the show...

“Can you image if we were all sitting around the table in RTÉ, before the Eurovision and Moya said ‘Now listen, Bill. This is going to make loads of money. You get out and write a piece’. That was nowhere near anybody’s mind. This was all about putting out something on the Eurovision stage that reflected well on Irish music and on Irish dance. And a lot of what I had done over the years, the work that influenced me and the work that I influenced – like everything I did with Planxty and separately with Andy Irvine – and the rock stuff that I did, and the jazz stuff, all of what goes into making me who I am as a musician – all of that came together in Riverdance.”