- Music

- 08 Nov 21

On this day in 1974: Thin Lizzy released Nightlife

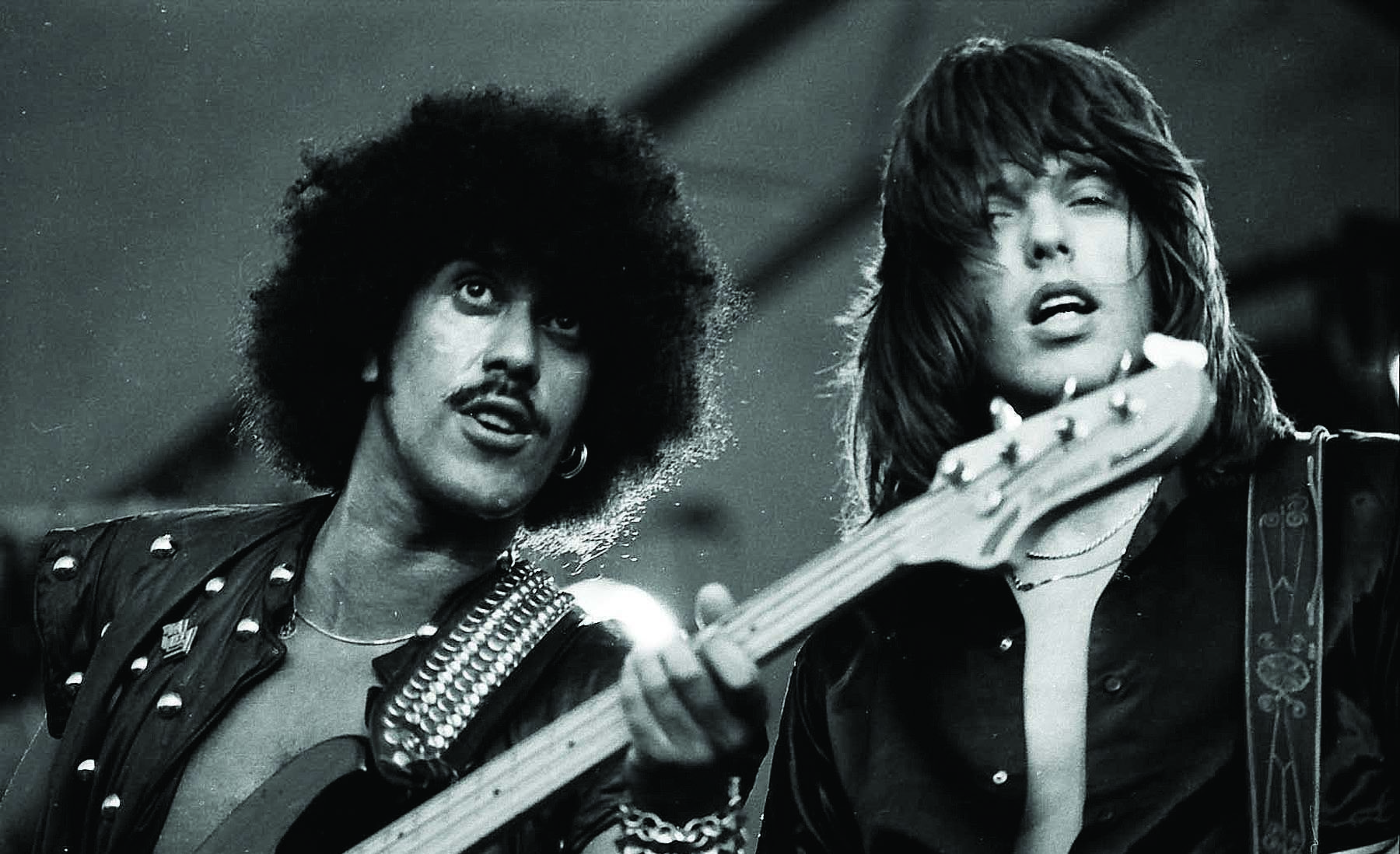

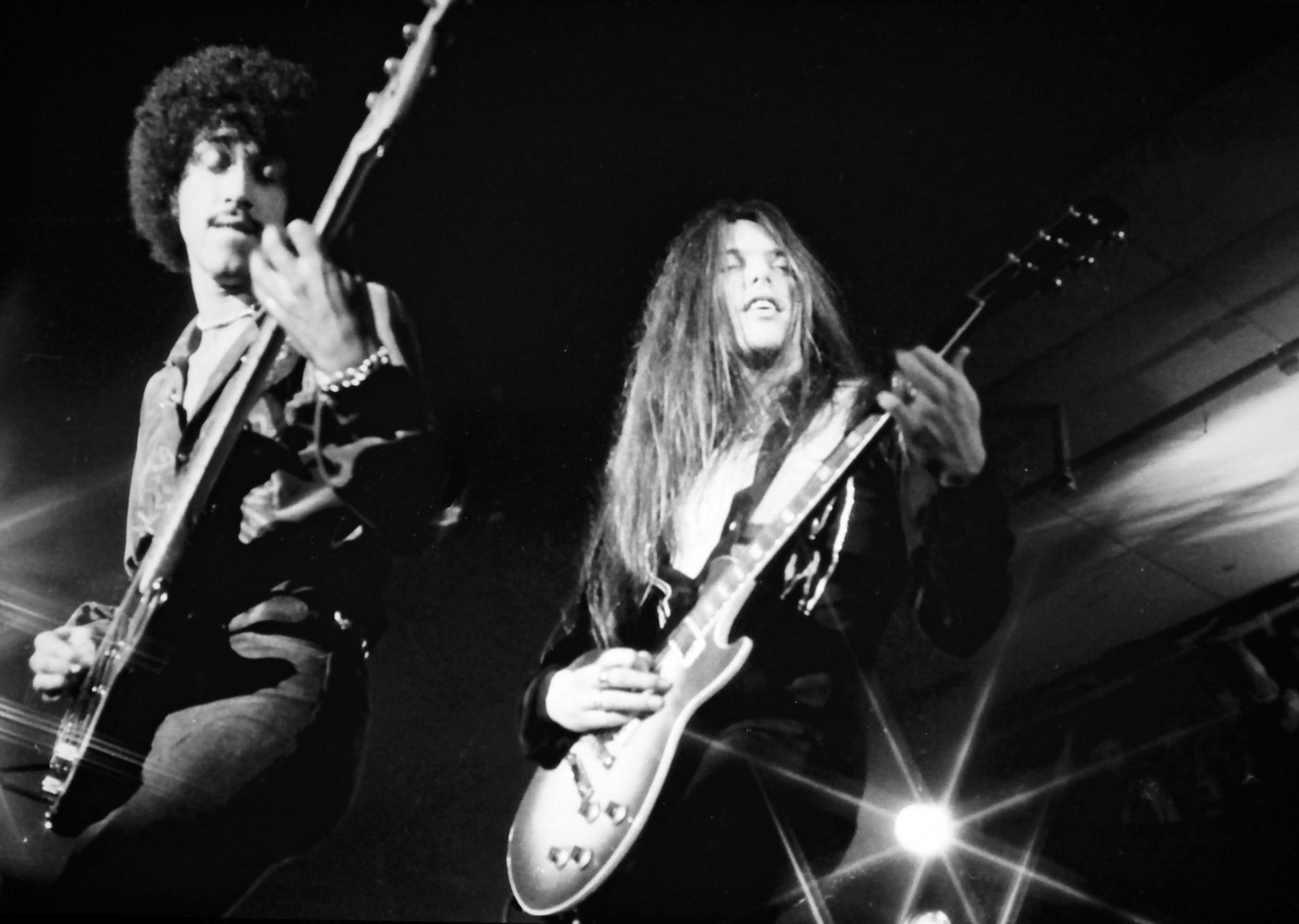

47 years ago today, Thin Lizzy released their fourth studio album Nightlife. It was the first LP to feature the band as a quartet, featuring Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson on guitars. To mark the occasion, we're revisiting a classic interview with Gorham – originally published in Hot Press in December 2020.

When Scott Gorham hooked up with Philip Lynott at a dinner club in London, it was the beginning of a close musical relationship that lasted for a full ten years, before the Thin Lizzy franchise was finally put on ice. To coincide with the release of Emer Reynolds’ documentary about the life and music of Philip Lynott, Songs For While I’m Away, we look back at that tumultuous and hugely successful decade, as Scott Gorham offers his portrait of the Irish rock icon.

Emer Reynolds’ Philip Lynott documentary Songs For While I’m Away is a rare artefact. Where previous attempts to examine the Thin Lizzy frontman’s existence have faltered, relying on the two-dimensional Celtic poet/hard-living rocker motif, Reynold’s portrait bravely attempts to capture the complexity of the multi-faceted icon.

For the first time, Philip’s wife, Caroline Taraskevics, is interviewed for a major documentary on the life of the Irish rock icon. The relationship between Philip and Caroline had split in the early-to mid-1980s, but they had never divorced. In the film, Caroline admits that – even after six years of marriage – she was only getting to know her husband, so the film-maker’s task was an onerous one, to say the least.

Here we are presented with contributors from every era and aspect of the musician’s life. Those helping to chronicle Philip’s journey include his uncle (and childhood friend) Peter Lynott, Brush Shiels, Eric Bell, Midge Ure, Jerome Rimson, Huey Lewis, Suzi Quatro, former girlfriend Gale Claydon, PA Diane Wagg, first manager Terry O’Neill, close friend Gus Curtis, his daughters, former wife Caroline and rock star fans like Adam Clayton and James Hetfield. Our own Niall Stokes, who acted as an advisor on the film, is a key part of the narrative also.

The documentary weaves these testimonies in with Phil’s voice and his extraordinary music, the story being told also through the judicious use of an array of childhood photos, old footage, memorabilia, potent images of Dublin and its landmarks, concert recordings and more.

Central to proceedings is Scott Gorham, guitarist with Thin Lizzy from 1974 onwards. He was Phil’s close friend, ally, comrade and best man. Witness to the rise. Witness to the demise. So who better to navigate the documentary subject matter – the life and times of our beloved Crumlin Cowboy, Soldier of Fortune, Renegade, Rocker (and Roller too, honey) – and much more.

“So, I’m in this African Dinner Club,” a familiar Californian voice announces, “and out of nowhere I hear this voice, ‘Are you Scott?’. It was Phil, but I thought he was one of the guys that worked there.”

Scott Gorham laughs. “I said, ‘Yeah, I’m supposed to meet a guy called Phil who’s with a band called Thin Lizzy. Can you show me what room they’re in?’ And he said, ‘Yeah I’m Phil’. And that sort of threw me – because he was black with an Irish accent!”

AN EXTRA WARM WELCOME FOR SCOTT

June 1974. Scott Gorham’s planned six-month stay in London is coming to an end. He has been busy playing clubs with his band Fast Buck and making musical contacts. One, by the name of Ruan O Lochlainn (who was in the Irish pub-rock band Bees Make Honey with Gorham’s future brother-in-law Bob Siebenberg) knew Phil Lynott and informed the young American guitar-slinger about auditions that were taking place. A gig as guitarist with an Irish rock band called Thin Lizzy was the prize.

“I knew absolutely nothing about them,” grins Gorham. “But Phil was great from the very beginning, really warm, and he had that big flashy smile of his. We shook hands and he said, ‘I’ll introduce you to the other guys’. So, from the start I felt really welcome.”

Of course the Lizzy that Gorham joined had three albums under their belt and a chart hit in the form of the Celtic rocker, ‘Whiskey In The Jar’. All these years on, the activities of the previous three-piece incarnation of the band are dealt with deftly in the film, the always amusing Eric Bell providing revealing and humourous insights. But was there a determination that the twin-guitar model – which emerged in 1974 – would be ground zero for the new group?

“Yes, absolutely. It was obvious that it was going to be a different band,” Gorham affirms. “The sound was going to be totally different anyway: there’s so much more you can accomplish musically with two guitars. I personally didn’t want to have anything to do with those first three albums – in my mind, this was a different group. Obviously, we had a leg-up, because of ‘Whiskey In The Jar’, but we were trying to make our way as a brand-new, revised Thin Lizzy. I had a few conversations with Phil about that, because worldwide Thin Lizzy really meant nothing. In fact, outside of England and Ireland they were either not heard of or not played. So, really, we were starting from scratch.”

Gorham had his own ideas about how this transition should be handled.

“I remember saying to Phil,” he recalls, “that we need to stand on our own two feet, so we ought to drop old numbers and just head out on our own – and that included ‘Whiskey In The Jar’ and ‘The Rocker’. And Phil agreed!”

He laughs. “If roles were reversed and another guitar player came into a band that I was in with Phil, and said ‘I think we ought to drop ‘The Boys Are Back In Town’ and ‘Emerald’, I think we would have thrown his ass straight out the door and got somebody else in! Years later, I think ‘How did I have the nuts to say that?’ In the end it worked out: people saw that we didn’t have to rely on the older songs.”

Aspirations for world domination aside, the new Lizzy could always rely on a devout Irish fanbase. Although he was warmly welcomed into the band by Phil, as an American, Gorham did have reservations about how he would go down with the loyal home crowd.

“I remember our first Irish tour culminated in a show in the National Stadium,” he states. “I was really nervous and I had confided to Brian Downey that I was afraid that if the audience didn’t like me, Phil might say, ‘Well this isn’t working out’. I know now that Brian told Phil, because at the end of the night when Phil introduced the band he gave me a huge build up, saying where I was from, what I was wearing… it went on forever! I’m thinking ‘For God’s sake Phil just get on with it, put me out of my misery’!

“So eventually, he said, ‘C’mon let’s hear it for – and he always pronounced my name Gurrum (laughs) – SCOTT GURRUM!’ Of course, because he had built it up so much, they went wild. I don’t think it was anything to do with liking me, I think it was because they knew Phil wanted me to feel extra welcome. It made me feel really accepted. I’ve never forgotten the Dublin audience for that.”

PHIL AND THE FANS

On that first Irish tour, Scott Gorham remembers being struck by Lynott’s fervour for his homeland, finding himself frequently the recipient of Phil’s latent tour guide tendencies.

“Phil was such a proud Irishman,” he asserts. “He would take me on walks around different cities and towns we played in Ireland. He’d be like, ‘See that statue over there… that guy’s name was so-and-so and the reason they have that statue there’ – and he’d give me the entire history of these people or a certain landmark! He knew Ireland inside out. He was this encyclopedic kind of guy when it came to Ireland.

“And the really bad thing is on our first tour in America, we landed in New York and as soon as the wheels touched down Phil claps his hand together, ‘Ok Scott, right, you’re the American here, what’s up with New York?’ And I just looked at him and said sheepishly, ‘I don’t know Phil, I’ve never been here.’ I felt really terrible!!”

Despite the optimism of the new four-piece and determination to make their mark, the first and second albums (Nightlife and Fighting) sold poorly. The pressure was on for their third release, Jailbreak.

“Historically you were always given three albums,” explains Scott. “You were never really meant to make it on the first; by the second you were meant to have honed your craft; and by the third you needed a big hit record or you got dropped. So here we are on the third album, record companies were saying you really need that hit, management were saying it, everybody knew it. So we doubled our efforts. We rented a farmhouse, brought out the eight-track recording machine and sat there for two or three weeks just really concentrating on the writing, hoping that something was going to hit. It was a concerted effort to really make the best album we possibly could.”

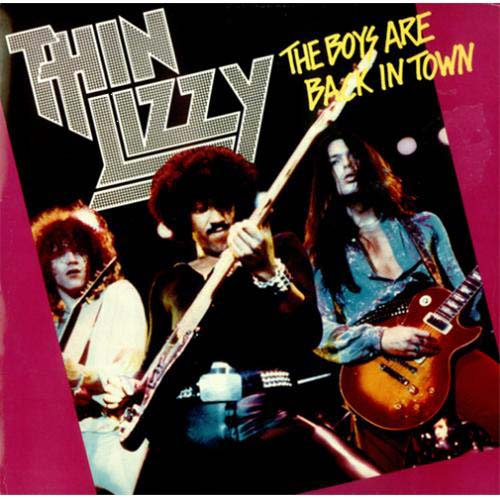

Luckily ‘The Boys Are Back In Town’ and its parent album delivered the required chart success. Now a classic rock anthem, the song is beloved around the globe. Apparently, the track was originally called ‘GI Joe Is Back’.

Gorham laughs.

“It sounds really dumb now, doesn’t it?” he chuckles. “I think the remnants of the Vietnam War were still there and it had really stirred up an anti-war feeling. But, finally, Phil said ‘Nah, that idea has been overdone, so many people have written anti-war songs’. He turned it into more of a gang song. He looked at all of us: what do we do on a Saturday night? We go out, we have a lot of drinks, try to pull the chicks and have a great time. And that is what that song is: it’s Saturday night with all your buddies. That’s what the song is all about, nothing more.

“Actually, I did an interview with this German guy, years and years ago, and he said, ‘Yeah, I want to talk about ‘The Boys Are Back In Town’ – I think I really understand the meaning of that song. The undercurrent is all about the IRA’,” says Gorham. “So I went, ‘Whoa! Whoa! Whoa! No, it is not. It’s nothing to do with politics or divided sides. It’s a good-time party song!’ After that this guy had nothing to talk to me about! He thought he had uncovered the secret meaning of the song. He was totally shattered: he’d thought he had broken a hidden code!”

While his songs were never overtly political, Lynott was passionate about politics in Ireland.

“He devoured the newspapers, watched the news, he was especially interested in events in Northern Ireland,” Scott says. “He was very well-read and used to explain to me regularly what was going on because I didn’t understand the background or the detail of the issue. He would go into the whole history, so I had a better understanding. So yes, he was very much a political animal. Not that you would hear about it in the songs. He didn’t want to push his politics on the outside world.”

Phil is known for his versatility as a songwriter. He could as easily compose a love song to his mother ‘Philomena’, his daughters ‘Sarah’ and ‘Cathleen’ or to his home city ‘Dublin’ as pen a thunderous battle song like ‘Emerald’ or a full-throttle rocker in the shape of ‘Are You Ready?’. In the film, Midge Ure speaks about it as a struggle, a “constant pulling, a toing and froing, between the sensitive poet and the rock star”.

Scott Gorham disagrees.

“I don’t think there was a struggle at all,” attests Gorham. “Phil would write songs and we recorded whatever songs he felt like recording. He was never afraid to show the hard gun-carrying kind of guy or the soft poetic person. He wasn’t afraid to show those different sides of himself. That was one thing I really loved about him. We are what we are. I am what I am. Love me or hate me.”

Gorham also remembers Lynott as an inclusive artist who ‘insisted on everybody writing’.

“His main mantra was this was Thin Lizzy, this isn’t Phil Lynott and Thin Lizzy,” he notes. “Whatever ideas you have, bring them to the table and hopefully we can make it work. I think Phil really loved the idea of having a partner: sure, he wrote the lion’s share of the songs, but it was good to have the pressure taken off him and have other people contribute. He was extremely generous: whatever you had, he was always trying to get it into a song and make it work. He was really great that way.

“One of his real strengths as an artist was the ability to recognise a good song,” he continues. “I would come up with a riff and he would immediately beam in on it and think, ‘I can make something out of that’. I was always really grateful to him that he could do that, because I’m not a lyricist by any stretch of the imagination. His ability to take a riff or a chord pattern and come up with a melody or lyrics with meaning, that always blew me away.”

His generosity in the studio was also a factor in his relationship with the fans. Phil had a policy of meeting and greeting people who lingered after concerts whenever the schedule allowed.

“The door was always open to fans who wanted to have an autograph or to have their picture taken or to just ask questions,” he says. “He would ask them questions too. He’d ask, ‘We put in a new song tonight what did you think of it?’ Or ‘We left out that song out, did that piss you off?’ It was like an information bureau, you could talk to the fans and see what they were thinking.

“Are we all on the same train here? Are we, Thin Lizzy, making the right moves for you the fan? I thought that was a really great idea. It got tiring at times, because you’d be exhausted during the tour, and more fans would keep coming in. But Phil had more energy that anyone I had ever worked with.”

LIZZY’S ROYAL FLUSH

This generosity was also present in band decision-making. Despite a tough exterior, Phil Lynott was never a dictator. Over his years in the band, Gorham was partnered with several other guitarists, including Gary Moore, Snowy White and John Sykes. The way Scott tells it, the final call on his sparring partner rested very much in the Californian’s hands.

“He was very much of the opinion, ‘You’re the one who is going to have to be playing with this guy and if you’re not happy we are going to have to find someone else’,” explains Scott. “He understood there had to be symmetry, you had to like each other and like each other’s style and work well together. So, I ultimately had the yes or no. I don’t think I ever said no, though. Why would I? They were all great players!”

As well as his Lizzy output, Phil also released the acclaimed Solo In Soho and The Philip Lynott album. Very often, when a front-man pursues side-projects, it results in intra-band feuding. Did Phil’s solo work cause any consternation in the camp?

“No way. Nobody wanted to chain anybody down,” states Gorham. “I always knew that Thin Lizzy was his number one love, plus it was a great safety valve. If Phil played a song and you didn’t think it sounded great you could say, ‘Hey Phil, that’s a really great song for your solo album!’(laughs) And he’d say, ‘Yeah! That’s great so that’s one more I have for the solo album’.”In order to tour the solo albums Lynott formed the Philip Lynott Band with musicians Jerome Rimson and Gus Isidore. For the first time in his career, it seemed he had a heightened awareness of his affiliations with black music. In ‘Ode To A Blackman’, which featured on Solo In Soho, Phil observed: “But the people in this town/ That try to put me down/ Are the people in the town/ That could never understand a black man.” Over 40 years later, those lines feel very contemporary.

In the documentary Jerome Rimson remembers: “People were saying stuff to this guy that was hurting him to his core.”

However, Scott Gorham doesn’t recall them encountering any racism.

“Unless there were racist people that wanted to pick a fight and used another excuse to pick the fight,” he muses. “Historically, if you go back, it seemed we were always in a fight with someone for whatever reasons. Maybe some of that was racial but then again maybe not.

“I remember we were in a hotel in Wisconsin and Phil calls me up and says, ‘C’mon let’s meet in the bar’,” Scott remembers. “I agree – and we meet in the bar. Immediately the DJ clocks Phil and really beams in on him – this must have been 1979. So we sat down and the guy keeps looking over at us. He finally comes over to us and the first thing he says is, ‘Wow, we don’t get many of your type in here!’.

“The conversation just stopped. Phil looked at him and then Phil looked at me and I thought, ‘Oh my god did this guy really say this?’. And then the guy says, ‘Yeah, Thin Lizzy man, I’m a huge fan! We don’t get many rock stars in here!’ It could have gone either way. We never really got the racist card pulled, because there were too many people that respected Phil so much that that subject really never came up.”

So where would Lynott stand on BlackLivesMatter?

“He would be a huge supporter, as I am,” says Gorham. ”There’s no doubt about it. He used to tell me he got picked on in school for his colour and his hair. But there are so many bullies in school... I think as soon as he got some notoriety that all went away. It was like colour didn’t exist with Phil.”

The mid to late ‘70s saw Thin Lizzy scale heights even Phil Lynott himself may never have the audacity to dream of. Jailbreak kicked off a recording royal flush with Johnny The Fox, Bad Reputation, the seminal Live And Dangerous and triumphant Black Rose following in quick succession. But it was when the band went to Paris to record the latter that the hard drugs came into the equation. By the early ‘80s, opioid dependence had started to affect their performances. Gorham remembers raising the gnarly topic with Phil.

“I had heard a live recording – I can’t remember where it was – but you could really start to hear the ragged edges of what was going on in the playing,” he recalls. “I thought, maybe that was a bad night. Then I heard another one and that’s when I went to Phil. I was feeling terrible at this time and I know he was suffering too. I said, ‘We’ve all put a lot of work and a lot of years into this band and now it’s being destroyed because of our drug habits. Why don’t we think about calling it quits or at least walking away from it for a couple of years?’

“Immediately Phil said, ‘No way, that’s not going to happen, forget about it’. I had to mention it a couple of more times. I didn’t want to see the reputation of Thin Lizzy being thrashed. Then we brought John Sykes into the band, who injected a lot of energy and we decided to do a last album and last world tour.”

Scott Gorham and Roisin Dwyer at the Covered in Glory event at the Irish embassy in London. Wednesday 6th of June 2018. Copyright Miguel Ruiz

Scott Gorham and Roisin Dwyer at the Covered in Glory event at the Irish embassy in London. Wednesday 6th of June 2018. Copyright Miguel RuizA TERRIBLE THING RIGHT THERE

Thin Lizzy’s final show was in Nuremburg in September 1983. Gorham says then when the end came, things were not really final.

“When we said goodbye in the airport, I don’t think anybody believed it was the end forever,” he says. “It was certainly the end for right now – and we would see what would happen down the road. We weren’t saying we were never doing it anymore. That was too much to even think about.”

So, when Scott Gorham looks at acts of a similar vintage, AC/DC for example, is there a pang of ‘if Phil had lived we could be out there too’.

“That’s a great hypothetical,” he sighs. “I would love to think that, and it’s certainly possible knowing Phil’s ultimate drive. I was at his house three weeks before he died, and he was talking about writing songs again, and getting the band back together. I was up for that – but I saw the shape he was in and he had a long way to go to put himself right. But I agreed with him. I always wanted to see Thin Lizzy come back together again. At that moment in time I knew it was not possible but, hey, down the road, why not? Absolutely!”

Considering the vast swathes of territory we have just covered I wonder what Scott feels about Caroline Taraskevics’ comment that she was ‘just getting to know Phil’ after six years of marriage.

“Well, he was a complex person,” concedes Gorham. “I think guys like Phil that have so much energy and talent, they go through a multitude of emotions. I imagine nobody could really say, ‘I knew Phil Lynott forwards, backwards and inside out’. Phil really was a complex guy, but I got pretty adept at reading him. I could tell when the moods were coming, and it was time to move out of the way. But does anybody really know anybody? I know that’s the old hackneyed phrase.”

Despite the number of years that have elapsed since Philip Lynott’s passing, Scott Gorham still finds himself regularly reflecting on Lizzy. Is there still a huge sense of loss?

“There is, but I don’t walk around thinking of Phil all the time and crying, because he has been gone for such a long time now,” he says. “I just think what a shame, what a waste, what could have been. If we hadn’t done the stupid things, how far could we have taken it? And I know we could have taken it much farther than we did. We got stupid. I don’t know why the drugs crept in the way they did, but it’s history – and we can’t do anything about it. It was what it was. Now we have to live with the consequences – which is a terrible thing right there.”

And if he could do it all again?

“Well, yeah, the whole drugs thing...” he says. “I would have knocked that on the head, because if we didn’t get into drugs the way we did, it wouldn’t be me you’d be talking to. It would be Phil.”

Revisit Nightlife below:

RELATED

- Music

- 17 Jan 26

On this day in 1974: Joni Mitchell released Court and Spark

- Music

- 25 Nov 24

50 years ago today: Nick Drake died, aged 26

- Music

- 13 Sep 24

Album Review: Bob Dylan and The Band, The 1974 Live Recordings

RELATED

- Music

- 21 Jul 24

On this day 50 years ago: Rory Gallagher released Irish Tour '74

- Music

- 17 Jan 24

On this day 50 years ago: Joni Mitchell released Court and Spark

- Music

- 25 Nov 22

Thin Lizzy

Thin Lizzy