- Music

- 05 Jan 24

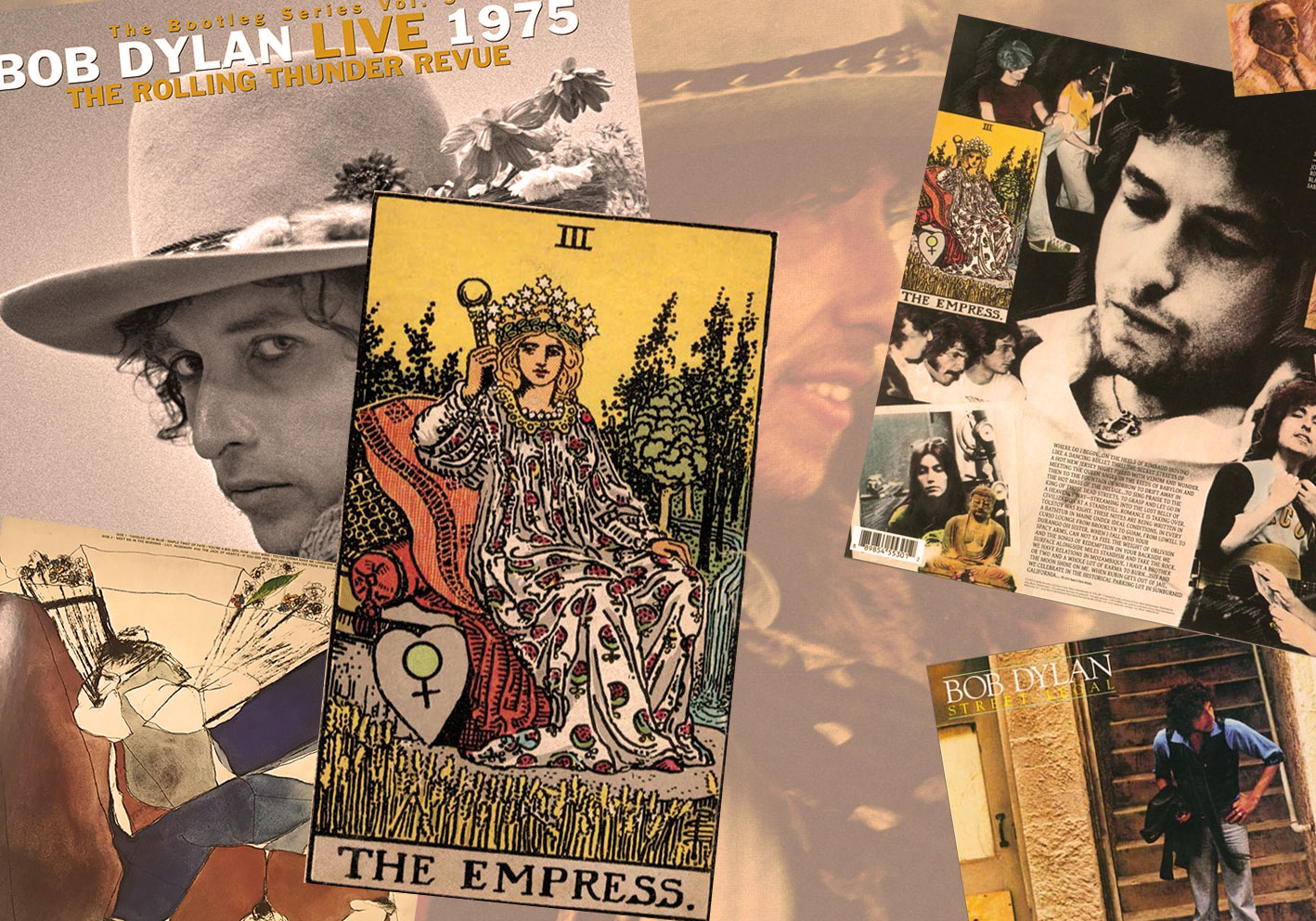

On January 5, 1976, Desire was released on Columbia Records – an LP, largely co-written by Jacques Levy, that found Bob Dylan joining forces with numerous musicians from the lauded Rolling Thunder Revue, while Emmylou Harris contributed backing vocals. Desire – which featured epic tracks like 'Hurricane' and 'Joey' among its highlights – has since been listed among the greatest albums of all time. To mark its anniversary, we're revisiting Pat Carty's reflections on this iconic LP...

The Masque Of Desire: A Bob Dylan Story

Originally published in Hot Press in 2021:

I’m on the phone to Niall Stokes. I’d sent him a vague suggestion about doing something to mark Bob Dylan’s 80th birthday, perhaps something about Desire, my favourite Dylan album.

The Editor isn’t sure. He thinks, like many people do, that Blood On The Tracks is the better record, and therefore the better choice. We bat it back and forth, like we always do, and, like he always does, he sets me off thinking.

Blood On The Tracks was released in January of 1975. It was met with mixed reviews, but has, of course, gone on to be considered by many, including my boss, as Dylan’s greatest record, an opinion that’s hard to argue with, because it’s brilliant.

Advertisement

Well, I don’t intend to argue, but to demonstrate. So pay your money at the door, get your tickets and find your seats. When the man with the bull-horn emerges from the wings, you’ll know it is time to start listening.

Scene I: A Man Sits Centre Stage, Alone

Nashville, February 1966. Columbia Studio B. Bob Dylan sits at the typewriter hammering out the kind of songs that no one had ever heard, while a team of crack musicians sits nearby, passing the time with hands of cards and cigarettes. He’s ready. This is called ‘Sad Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands’. Charlie, it goes like this. Four takes. Three completed takes. Done.

Dylan in the mid-sixties was flying at an altitude that few, if any, others would ever reach. He seemed so sure of himself, and even when there were crowds howling for his blood, he just turned around to The Hawks and said, “Play it fucking loud.” We get to the writing and recording of Blood On The Tracks and Dylan had taken a few knocks, and none of them hit harder than a marriage that had run its course.

Dylan has always said that those songs, those beautiful love songs of real life, were not personal. He pointed towards their flexible relationship to our notions of time as having sprung from his classes with the painter, Norman Raeben; or he’ll say that they’re related to short stories by Anton Chekov, as he did in his brilliant autobiography of a sort, Chronicles, Vol. 1. I suspect – and these pages are naught but scribbled thoughts – that this is smoke designed to throw us off the trail.

I think Dylan knew these songs were special, more personal to him than others he had written. His first instinct was to record them with a full band, including Mike Bloomfield, the man whose guitar we hear on ‘Like A Rolling Stone’, but he decided they suited a sparser setting; the words needed to be heard. He recorded at his usual pace in New York, although this time the songwriting was finished in advance, showing any musicians who didn’t get it, the door. The company men geared up for a Christmas release, and then Bob actually listened to someone else. He doubted himself. His brother told him he could do better, and he was right.

Advertisement

There was another session in Minneapolis, five songs were replaced on the album, and within a month it was in the shops, because things were different in those days.

Can we then see Desire as a reaction to all this? Did Dylan – a man who rarely gives anything away – feel he had revealed too much? Did he then seek to hide himself away again with his next turn, behind masks and make-up, behind a raggle-taggle band, behind lyrics that told stories that were not his? Yes? No? Let us speculate.

Scene II: A Bar In New York

Dylan is in the south of France in early 1975, arsing around with the painter David Oppenheim, whose drawing is on the back cover of Blood On The Tracks. He moans about his marital troubles but that doesn’t stop him drinking and carousing. For Dylan’s birthday on May 24, the two pals go to a gypsy festival in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, where Dylan meets the Gypsy King.

Dylan gets back to New York in June. The wife and kids are on the West Coast. He hangs out. Slowly, the next chapter starts to fall into place. He goes to The Other End club – better known before and after as The Bitter End – and sees the Patti Smith group before the release of Horses. He sees Muddy Waters. He starts to think about bands again. He gets up with Ramblin’ Jack Eliot in the same club in July, and plays a new song called ‘Abandoned Love’ to a hushed room.

“My heart is telling me, I love you still”

Advertisement

He makes new friends. This story is so crazy it has to be true. He spots a good looking woman carrying a violin case in the street; he pulls his car over and persuades her to get in; he takes her to his place and plays her another new song he’s working on. She adds her violin to it and he likes what he hears.

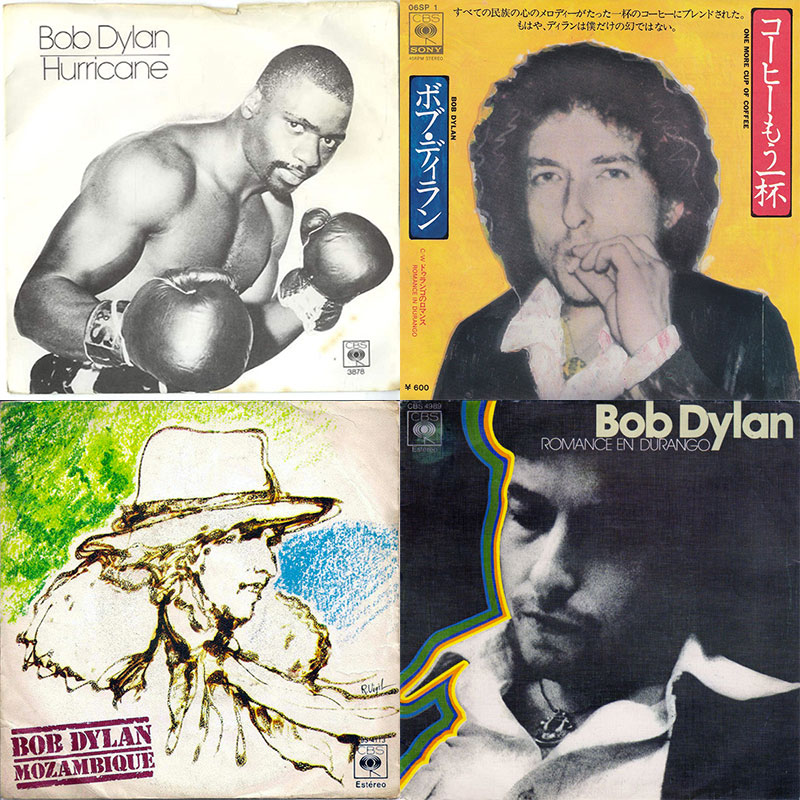

Her name – the name she’s chosen for herself – is Scarlet Rivera and she’s in. The song is ‘One More Cup Of Coffee’, full of references to the gypsy king he met in France, but what is the “valley below”? Is it perhaps connected to the last line of ‘Abandoned Love’, “Let me feel your love one more time before I abandon it”: is that the one last cup of coffee before he goes? There’s another song that wouldn’t make the finished album called ‘Golden Loom’, where he sings, “I kiss your lips as I lift your veil, but you’re gone and then all I seem to recall, is the smell of perfume.” He might point towards the short stories and the paintings of others, but these are the lyrics of a man missing something that has been lost.

That same summer, the theatre director, Jacques Levy, shouts Dylan’s name at him in the street. They’d met before when Levy worked on songs with Byrds main man, Roger McGuinn, as part of an abandoned musical based around Ibsen’s Peer Gynt. One of these, ‘Chestnut Mare’, was the last thing even close to a hit that The Byrds would enjoy.

The two men go for a drink, and Dylan talks about them writing together. They go back to Levy’s place. Dylan plays ‘One More Cup Of Coffee’ and another new song, ‘Sara’, on the piano. Dylan has the bones of ‘Isis’. They work on it together.

The friendship tightens and, after a few weeks, they head out to Dylan’s house in Long Island to get some more collaborating done. They also bat ideas back and forth. ‘Romance In Durango’ springs from a picture postcard, they play a game to see how many things rhyme with ‘Mozambique’, and they take up the story of slain gangster Joey Gallo, because Levy knows people who knew him.

Scene III: Columbia Recording Studio E

Advertisement

Dylan pulls a band together out of the Greenwich Village scene he’s built around himself because he doesn’t want to be alone. He’s in The Other End again, watching old pal Bobby Neuwirth (the other man in the shades in Don’t Look Back). Neuwirth’s show is a knock-about revue, with various musicians being invited in, including honchos as different as T. Bone Burnett and Mick Ronson.

Dylan is there every night and the two old friends, Bob and Bobby, wonder if they could get away with taking this kind of thing out on the road. Rob Stoner is there too, playing bass with Ramblin’ Jack Eliot. Dylan had met him a few years before on the west coast. The ingredients begin to coalesce.

Before going on the road again, he needs to record the new songs. His first attempt is on July 14. Rivera is the only one of the Village gang invited but Dylan goes with the bigger band notion that came to him in the after hours, calling on former Traffic man Dave Mason and his band, as well as a trio of backing singers. ‘Joey’ and ‘Rita May’, another Dylan/Levy number, are attempted, but the results are shelved. He’ll come back to the backing singers idea later.

Dylan perseveres with it. He’s back in Columbia Recording Studio E on July 28, with more than twenty musicians: horns, mandolins, accordions and a handful of guitarists, including one Eric Clapton, who has a hard time figuring out what’s going on. He isn’t the only one either. Rivera’s lack of experience leaves her adrift, and the great Emmylou Harris, perhaps brought in because of her immortal work with Gram Parsons, has a tough time of it too. It’s difficult to sing harmony on songs you haven’t heard before.

It falls to Rob Stoner to suggest to the then-inexperienced producer, Don DeVito, that what’s needed is a small group of musicians who could help Dylan capture those early takes he prefers. Accordingly, those who aren’t needed are out. A core band of Harris, Rivera, Stoner, and his drummer mate Howard Wyeth are gathered on the night of July 30. It is one of those special nights. Everything works. Before they spill out of the studio, blinking in the light of the morning, they finish takes of ‘Isis’, ‘One More Cup Of Coffee’, ‘Hurricane’, ‘Oh Sister’, ‘Black Diamond Bay’, ‘Joey’ and ‘Mozambique’, as well as the to-be-relegated ‘Rita Mae’ and ‘Golden Loom’.

The heavy lifting is done but Dylan is back at it again the following night. This time his wife Sara comes to the studio, and as she looks on, he records the final version of ‘Isis’, ‘Abandoned Love’ and, after telling her, perhaps unnecessarily, that this one is for her, ‘Sara’. The pain is still there in lyrics like “Whatever made you want to change your mind?” and “You must forgive my unworthiness.” Most especially, there is that last lingering line, “Don’t ever leave me, don’t ever go.”

One last bit of recording remains; there is a problem with ‘Hurricane’. Dylan had first heard the story of Rubin Carter, the boxer who was in prison for a triple murder that took place in Patterson, New Jersey in 1966, when Carter sent him his autobiography, which Dylan read on the trip to France when he wasn’t on the pull and the wine. He visited him in prison and then got to work on the song with Levy.

Advertisement

The men in the Columbia Records law department fretted about a line that accused “witnesses” Alfred Bello and Arthur Dexter Bradley of robbing bodies. Dylan most likely thought this was fair enough, but DeVito’s production hadn’t separated the tracks enough to allow Dylan to just redo his vocal so the whole song had to be re-recorded that October. With Emmylou Harris off doing her own thing, Ronnie Blakely provides the harmony vocal.

Intermission: A Young Man Flicks Through The Racks In A Small Record Shop

It’s this version that opens the album Desire, released on January 5, 1976, only a year after Blood On The Tracks – aficionados will recall that The Basement Tapes came out during the summer between them. ‘Hurricane’ had been released as a single earlier, in November 1975, and it was a sizeable hit, reaching No. 33 on the Billboard charts. There was still an attempt at a lawsuit, from Patty Valentine, but it was thrown out. It became the most famous song from the album and it was the one that, when heard on some radio show, persuaded me to invest.

Dylan looks particularly cool on the cover, in a fetching hat and smiling as he was pleased – so journalist John Balfe told me recently, because Ken Regan, who took the photo, told him – with the coat, which he’d just bought in a second-hand store. Cooler than he did in the shades in the mid-sixties? It’s a serious and important question, but either way, I know for sure he looked better than he did in the eighties, when I took it home.

Scene IV: A Man Sits At A Desk.

A Record Plays In The Background

With the finished album now before us, I can go back to my original premise about Dylan hiding in plain sight. How does it stand up? The music and arrangements on Desire are some of the best he’s ever presented, and a lot of the credit for that sound must go to the two women involved, Scarlet Rivera and Emmylou Harris.

Advertisement

Emmylou’s voice adds a whole other dimension to these songs, which is even more praiseworthy when you remember that she didn’t know them. She was watching Dylan’s mouth for the changes – which is why, as she has explained, there’s a lot of humming on the record: she simply didn’t know where he was going to go next. As for Rivera’s violin, has Dylan ever, at any other time in his recorded career, given so much of an album over to another instrumentalist? If he wasn’t hiding behind them, then he was at least hiding beside them.

Let us examine Jacques Levy’s contribution. Why did Bob Dylan, very possibly the greatest songwriter to ever circle a semibreve, decide to take on a collaborator at all? Possibly because, after Blood On The Tracks, he wanted to write a different kind of song, with stories other than his own, and Levy helped him do that.

‘Romance In Durango’ is an example – although in truth we could take any of the songs and make a similar case. The lyrics read like a movie script, or, at the very least, theatre directions. “Hot chilli peppers in the blistering sun, dust on my face and my cape,” Bob Dylan sings. We could be looking at the opening scene to some long-lost follow-up to Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid – wherein Dylan’s Alias has gone on to further adventures, on the run now with Magdalena.

In fact, the death scene, in which the narrator asks his companion to “Come sit by me, don’t say a word, Oh, can it be that I am slain?” – while what certainly sounds like Roger McGuinn’s 12-string chimes in the background (‘Durango’ was the only cut to make the album from the “big band” session) is at least the equal of Sheriff Colin Baker, sat by the water one last time, as ‘Knocking On Heaven’s Door’ plays.

There’s the same cinematic/theatrical air to ‘Hurricane’ – “Pistol shots ring out in the barroom night, enter Patty Valentine from the upper hall”; and to the scene on Conrad’s island in ‘Black Diamond Bay’ – “A soldier sits beneath the fan, doing business with a tiny man, who sells him a ring.”

Similarly, ‘Isis’ would work as a complete script to some sort of Indiana Jones-style knockoff. The narrator heads off to the wild country, for to prove his worth to his love; he hooks up with a stranger, they go grave robbing, but the casket is empty, no jewels, no nothing. Does he then kill the stranger? At least he gives him a decent burial, before heading back to the woman he loves.

If Martin Scorsese is stuck for his next project, he could do a lot worse than buy the rights to ‘Joey’. The directing has very nearly already been done for him, right down to Joey’s demise. “One day they blew him down in a clam bar in New York, he could see it coming through the door as he lifted up his fork, He pushed the table over to protect his family, then he staggered out into the streets of Little Italy.”

Advertisement

We should note here that Dylan got some stick over this one as well. Joey Gallo, an enforcer in the Profaci crime family, was hardly anyone’s idea of a good guy – although he was certainly a goodfella – and the late, great Lester Bangs accused Dylan, in The Village Voice, of falling for mobster chic. Dylan’s defended himself by pointing to the folk tradition, which stretched all the way back to ballads about outlaws in the forest near Sherwood. At this point, the fact that it’s a great song is surely all that matters.

‘Sara’ – the song recorded in front of his wife – was Dylan’s alone. He couldn’t help but write one last song directly to her. By the time he got to the criminally underrated Street-Legal in 1978, he had gone through the divorce. He would never let the mask slip again.

One final word on those masks and disguises. Dylan did take his adaptation of Neuwirth’s Other End revue out on the road. The Rolling Thunder Revue played small venues across America at the end of 1975 – starting symbolically in Plymouth, Massachusetts – and surfaced again, following the album’s release, in the first couple of months of 1976.

This rambling caravan – with the likes of Allen Ginsberg and Joan Baez in tow – would be the most theatrical tour of his career. The music was fantastic; you can hear it on the glorious Live 1975: The Rolling Thunder Revue entry in the on-going Bootleg Series, his greatest live recording and yes, I’ve heard Volume 4 from 1966.

You get even more of a scent of the greasepaint off his sprawling “epic” movie Renaldo & Clara, but rather than subject yourself to a dodgy bootleg of that, watch Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story By Martin Scorsese, which is still showing on Netflix at the time of writing. It is, of course, a pack of lies and smirks, a story retro-fitted with a tongue so far into its cheek that it’s broken though the flesh, and you can read all about it elsewhere on hotpress.com where I poke several sticks at it, but never mind that.

In the film, you can see Dylan hiding behind white make-up, something he never did before or since; musicians and poets enter and exit, all stage-managed by Jacques Levy, who is criminally all but cut out of the finished film. Dylan’s mask might have slipped off for Blood On The Tracks – but with the help of his collaborators, he had it back on for Desire and The Rolling Thunder Revue. He wears it still.

Advertisement

“When somebody’s wearing a mask, he’s gonna tell you the truth,” Dylan says, to the camera, in Scorsese’s story, repeating something Oscar Wilde had said more than a century before.

He’s covering himself again, hiding in plain sight. Or is he? Who’s to really know? Perhaps the previous pages are themselves just another theatricality, presented for your passing pleasure by a man wearing his own mask that he keeps in a jar by the door.

“Everybody’s wearing a disguise, to hide what they’ve got left behind their eyes.”

Bob Dylan. ‘Abandoned Love’. 1975.

Lights fade.

Curtain.