- Music

- 01 Jul 23

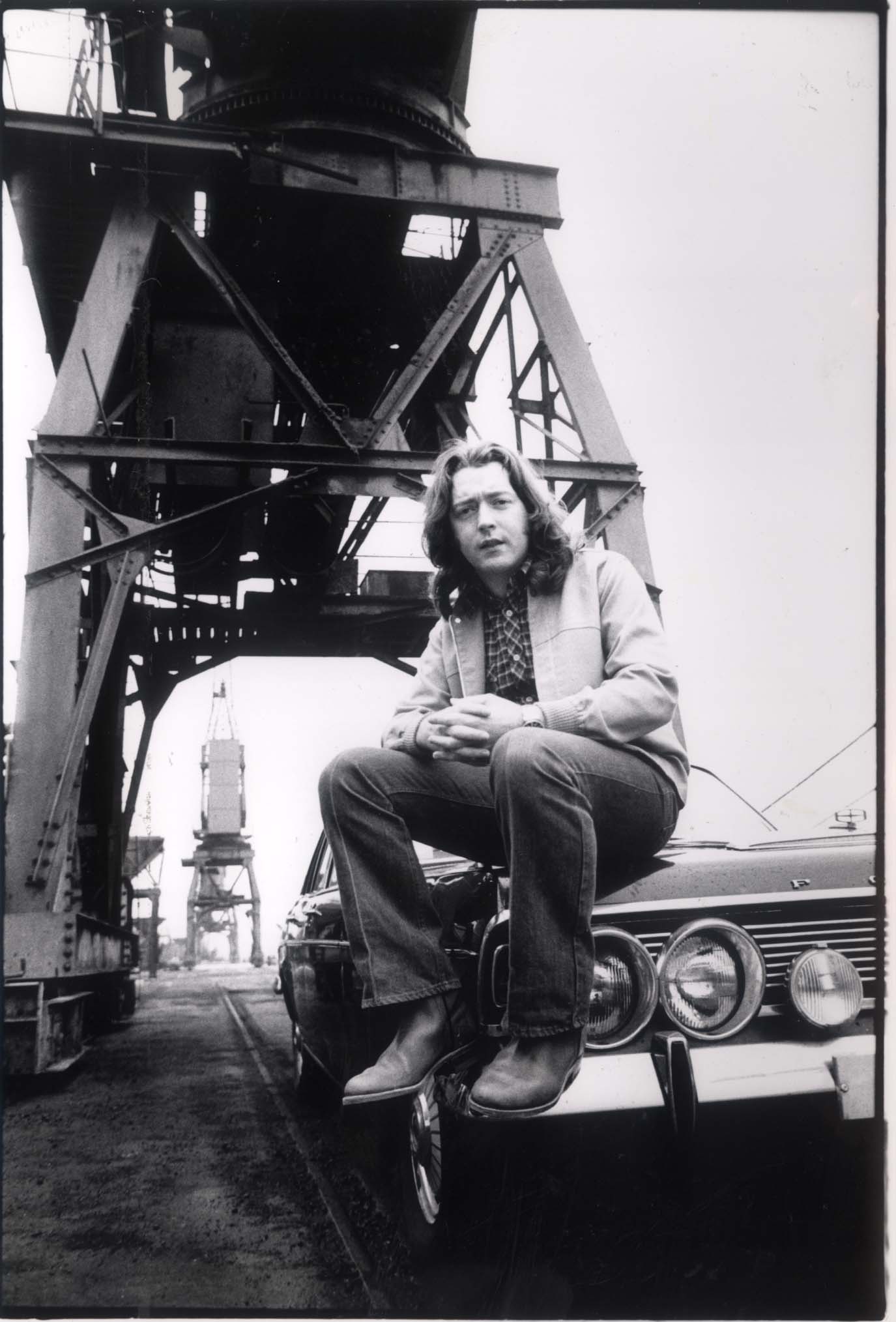

On this day in 1987, Rory Gallagher released the iconic Defender – his first studio album in five years, following 1982's Jinx. To mark the occasion, we're revisiting a classic interview...

After a recording silence of five years, Rory Gallagher returned towards the end of 1987 with Defender, regarded by many critics as his finest album to date. In Dublin for a series of storming gigs at the Olympia, in a wide-ranging interview at the time, he spoke to the late Bill Graham about Ireland in the showband era, his early experiences playing in the sleaze pits of Hamburg, his rediscovery of the blues – and the longstanding love of the thriller genre which informs his latest album.

Originally published in Hot Press in 1988...

"Maybe people thought I was sheep–farming,” Rory Gallagher ruefully remarks about his five years’ exile from Irish stages and record–shops. Of course he did join the Self Aid party in ‘86 and RTE recently filmed a Cork concert – but Rory Gallagher could be forgiven for worrying that he’d become a non-person among the Irish music fraternity in the long hiatus since his last major tour.

The afternoon before the first of his four Olympia concerts, and even a vastly experienced performer like Rory can seem a trifle nervous. It might just be this self-confessed insomniac’s means of psyching himself up – but Rory Gallagher could justifiably be anxious that he’s become a kind of historical figure – an icon unknown and unapproachable to a new generation of Irish music consumers, who presumably associate him with check shirts and their own hazily-remembered prepubertal ‘70s, when the guitar was God and video-pop purely a science-fiction concept.

His staunchly, even obstinately, independent values date from a more obviously oppositional time, when rock hardly merited a mention in the Irish media. He says he doesn’t want to be thought “an old fogey” – but surveying the evolution over the last 20 years, Rory Gallagher has both the right and the authority to argue that “rock and pop in this country has become very respectable, whereas it used to be a bit outlawish and frowned upon. But mums and dads now aren’t afraid to have their kiddie in a rock band.”

Advertisement

He’ll qualify his comments by admitting that they might include “some inverted snobbery on my part” and that current prosperity was obviously fated to include some measure of co-option. But as you listen to Rory Gallagher recalling his apprenticeship, you recognise his values were forged in a vastly different Irish popular culture.

In Rory Gallagher’s case, Bruce Springsteen’s mythic celebrations of rock’n’roll liberation actually make sense. Choosing his vocation – and for Rory Gallagher, it was definitely a vocation – was a brave declaration of personal identity with a real ethical component, and not a mere improvisation in fashion.

Come and get these memories...

“When you leave Cork docks on a van that is literally held together with plastic bands and you’re heading for Hamburg and you arrive there and see the conditions in the club where you have to sleep – that, in all modesty, takes a lot of guts... I remember going to England in a van, getting there and finding the two weeks of gigs we were promised didn’t exist and you’re standing in a phone-booth trying to get through to the agent. I tell you, we had some real close calls.”

This was before Taste eventually signed to Polydor; at that point, others in Gallagher’s position might have settled into a cushy gig with a showband. “You could really say to hell with it,” he continues, “and go home and get three meals on the table each day. It would have been very easy to take the £50 a week (worth four/five times that now – B.G.) gig with the showband and enjoy an easy life. But it didn’t cross my mind.”

It was Rory Gallagher’s own moral, pro-life decision. “I was totally opposed to it,” he reflects on the showband syndrome. Besides Hamburg has shown him wider horizons: “The first time you get up on a little stage in Hamburg and you do six sets a night with 15 minutes off every hour – there might be five people there. But just to play ‘Nadine’ by Chuck Berry without anybody giving out to you... Well, we did get our flow.”

Advertisement

Hard times and hard labour at 3.30am, when there’s nobody left in the club. “And the boss or one of his cronies insists you haven’t finished yet, you must play on. And your hands! Like, you’re talking blisters on blisters.”

He smiles and continues with a droll understatement in the laconic Cork mode: “The first guy we met over there, he definitely wasn’t a member of the Legion of Mary. But when you’re 15 or 16 that little bit of greenness or naivete keeps you going. You think ‘that poor man has to keep the club going, I suppose’. Besides if you didn’t do it, you’d be beaten up or something!”

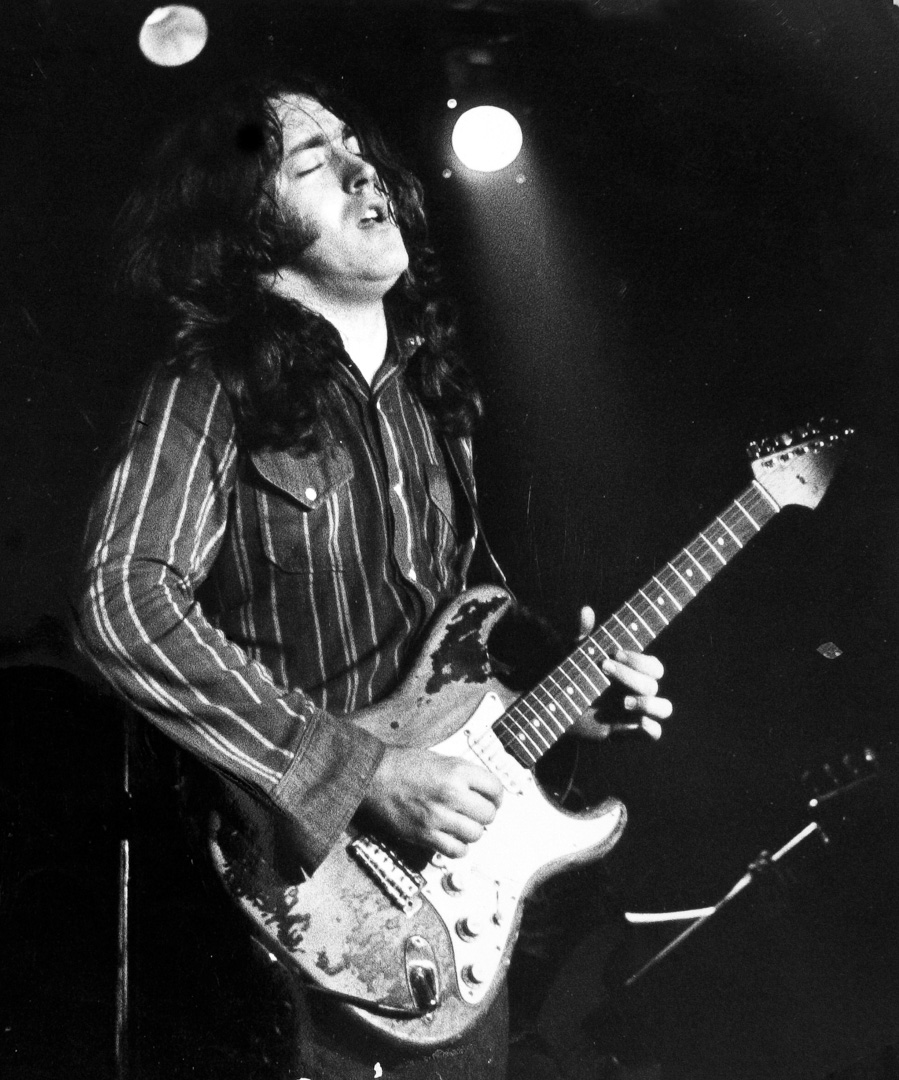

Thus Rory Gallagher learned stamina and independence. Throughout the late ‘60s and ‘70s, Rory, with or without Taste, epitomised the working musician, stubbornly doing it his own way without a lick of fashion, rising in an era before glam merged with hard-rock, when blues was still an accepted part of the form’s vocabulary and the guitarist regularly took precedence over the singer.

He’s somewhat mysterious about his career–break. Not that Rory Gallagher did take up sheep-farming. He still retained an on-the-road involvement, touring to loyal audiences in Europe and America. But, patently, Rory Gallagher’s deep-seated values were out of sync with a record business whose favoured role-models in hard-rock were Van Halen, Bon Jovi and Def Leppard. Even now he freely admits, “I’d rather play in the Shadows than Bon Jovi.”

In ‘82, his Chrysalis contract ended. Rory Gallagher was still selling records but what seems to have transpired was a typical, if under-reported ‘80s music business phenomenon – of an experienced artist believing he deserved both artistic independence and a decent advance in return for past sales and services, in conflict with the new breed of record company executives, who were thinking of mega–sales in the global marketplace with more compliant, younger acts.

Gallagher’s own comments are careful: “We were talking to certain companies and it was a case of ‘we’ll sign the deal, next week’. But you’d have certain artistic pressure on you and so on, and it was on that point that the deals usually fell down. Because a lot of record company people would be suspicious of me for not being too commercial or being too obstinate. So a lot of deals fell down, which caused a lot of tension for me, in myself.”

His own values being forged by live performance, Rory Gallagher couldn’t accommodate to the distancing, alienating, packaging of the video age, which downgrades the stage in favour of sitting-room consumption.

Advertisement

“Now, it’s the project, the stew, the movie. Everything has to be Cecil B. De Mille. There’s no such thing as a piece of funky music that comes out on the street by semi-accident. Even though I had nothing to do with punk or the early new wave, that was the side of it I liked – that you could go in at the weekend and not have a Tchaikovsky hangover about it and it could be out on the street two weeks later. And there was no great worry about it being on Top of the Pops as long as it paid for the petrol and the van to do a couple of gigs.”

Finally he formed his own record company, Capo, and linked up with lntercord on the continent and Demon in the U.K. to release Defender late last year, a set of carefully-conceived modern R&B songs that suggests the recording hiatus also prompted an artistic re-assessment. He doesn’t demur.

“You know how legal things take forever and people want packaging so it’s almost more important than the music – in a roundabout way, all that allowed me to get totally cheesed off and angry about the whole thing and in the throes of that, I had plenty of time to detatch myself and listen a little bit...

“I suppose it’s great to be on a label, working to a deadline and doing lots of tours – but you can overdo it and I probably did more than most. You can lose the purity of it or the self-knowledge. What happened was that you’d do a tour, go back to your place wrecked after it and you’d sit down and play acoustic blues. I’m not saying we were getting too rocky but, put it this way, things worked out for the better.”

He also believes he had been shunning the “common language” of the blues, “trying too hard to do something completely original which I achieved here and there on certain songs like ‘Philby’. But if you work too hard on that, sometimes you don’t have enough fun at just playing the groove. Plus with my listening at home I just played more blues records. I became more of a blues fan than I had for a while.”

Thematically, Defender may be Rory Gallagher’s most consistent and composed record, fusing his musical pre-occupation with the blues with a second obsession – his fascination with film noir and thriller authors like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. Defender chases down grittily realistic and not deglamourised versions of the Outlaw Blues myth. In the past, Rory Gallagher may not have been the obvious Irish candidate for songpoet status but on Defender his characters exist on a credible borderline of the law, trapped in ‘Kickback City’ with the ‘Loanshark Blues’ where “morality” is the property of the prosperous.

Advertisement

Defender may not be a wholly original concept – after all, musicians have always wanted to recapture the violin cases from the hoods – but Rory Gallagher doesn’t talk like a dilettante.

“I suppose I’m no great fan of the law or detectives, because they’re not always the nicest people – but in the movies they‘re always interesting because you don’t know their past. They just arrive in a city and set up an office. I’m not interested in the violence, it’s the characters, the remarks they make and the loyalties: particularly the code of honour between police and thieves in the French gangster movies. I mean there’s eating and drinking in all that stuff.”

Sounds like in the 20 years on the road since Hamburg, you can learn a lot in late-night bars?

“Anybody who’s travelled in America, bit by bit, you realise the gangsters aren’t the guys in the grubby suits anymore. I won’t mention Las Vegas, but we’ve been close to a few corners. But I wouldn’t be tough enough. I couldn’t pretend I’d hang out in the sleaziest joint in town just to get a story or a line.

“If you’ve done 25 tours in America and almost ended up moving there and still might, well, we really blend in over there so it’s gone past the point of ‘Hey you guys, are you from Ireland?’. So in Detroit, you know it’s a nod and a wink, do you know who owns the place? America’s gone past the point of pretending it’s a moral set-up anymore.

“I suppose every place has, really” – he trails off before continuing – “but that’s not really the germ of the thing. The guys in these books appeal because they’re up all night, so it’s really a parallel life to an insomniac musician.”

Advertisement

Rory Gallagher’s other enduring obsession is the Blues. The passing years have proved this is no affectation of youth. Other guitarists of his era may have passed onto technoflash or Gothic horror, but Rory Gallagher has remained loyal to his first musical love. Sometimes I suspect he’s really a denim-disguised Irish folkie, albeit one who channelled his historical passions into a foreign musical form.

His first encounter was instinctive, not academic. “I suppose I had the slight benefit of hearing it before I knew what it was,” he muses. “By the grace of God, because I didn’t have a record player, I heard the primal blues radio recordings of Leadbelly and Big Bill Broonzy. AFN was playing them on jazz programmes and also, BBC. Then there was Chuck Berry and Eddie Cochran – so it wasn’t too far to discover Muddy Waters and Jimmy Reed. And then there was The Rolling Stones and of course, the so-called blues boom.”

That later ‘60s phenomenon he now judges “had both good and bad moments. It was a very London thing with John Mayall, Fleetwood Mac and Chicken Shack and they were so po-faced about it. Good players but professors of the Blues – so a lot of them missed the emotion of it. Americans like Mike Bloomfield and John Hammond were looser about it.”

“And,” he continues, “any black bluesman, if I have to use the term, that I might have met – they might be angry but they never had the sort of European angst we suffer from. I think I’ve been able to get over that and enjoy the lyrics and the rhythm of it. I almost don’t have to worry about that because I need the music. It’s like bread and butter to me.”

How does it talk to your soul?

“It’s like the true creed. When all else fails in other aspects of life, in business or whatever, I can play a blues record. It’s as natural for me, as wholesome for my soul and heart, as probably traditional music is to somebody in the West of Ireland, who absolutely needs that music on a spiritual level.”

He continues: “I’m also interested in the itinerant music, the street-singers and the country-blues men.”

Advertisement

Is that an increasing point of personal identification?

“Something like that, I suppose,” he accepts, “though there’s nothing nice about travelling around rough. But a lot of those blues guys were just romantic figures. It didn’t mean they didn’t have a good suit and a good guitar, but they’d be staying at boarding houses, moving on one step ahead of the law or running away from their second ex-wife.

“Moving on beyond the county line! I know that’s a very comic-book version of their lifestyle, but I mean part of Presley’s appeal was that he might have looked as if he had a million dollars but when he came out first, he did look like he was getting out of town before midnight.

“I can’t sit down and write songs like ‘It’s 12 o’clock/ got the blues’. Even now it’s well-worn,” he adds, “I think putting a more moody melancholy anger in a character in a song is more original. I suppose the nearest songs on the album to a traditional blues is ‘I Ain’t No Saint’ which could have been done by Albert King or Albert Collins. But you want to be a unique character like BB King to write as cliched a song as ‘It’s two o’clock in the morning’. He can do it, I can’t. You always want the X-factor. I wouldn’t want to work so stringently within the blues tradition that I couldn’t put a middle-eight with nothing to do with the blues in a song.”

And he later adds, “I can’t write moon-in-June songs. I don’t like those singer–songwriter songs that reek of introspection.”

To the folk ethic: in his disdain for commercial pop values and his interest in history, craft and virtuosity within an indentifiable community where music has a straightforward social purpose, doesn’t he share similar values with traditional musicians?

“Yeah,” he agrees before pausing to ponder. “I like the old test of the man or woman who can stand up and sing or play unaccompanied without the whole malarkey. And so often today, it’s a visual not a soul or organic thing.

Advertisement

“But to be absolutely honest,” he reveals, “I didn’t always have this respect for traditional music. When I was growing up, I didn’t want to hear come-all-yes. I could appreciate a good piece of music on a fiddle – but to me, like every other kid, it was old fogey and boring. I just wanted to hear an electric guitar from America. But then, as the years progress, not only do you re-hear Irish-music properly, but you also appreciate its values – the selfless way people play.”

In the ‘60s, he adds, “I suppose the Gaelgoirs didn’t help. It was all rather snobby and off-putting. It was like compulsory Irish but that’s changed now, as well. People like the language more than when I was growing up.”

Despite his reluctance to appear academic, Rory Gallagher has inevitably become his own professor. After an hour’s conversation, you realise how much musical lore has been filed away in his memory-banks. Yet even as he approaches his forties, entertainment still takes priority over education on his spectrum.

“I suppose I’d like to be a crusader for the blues,” he admits, “but in a very subtle way. I wouldn’t want to preach it in a too intellectual way; even though I might know a fair bit about it, I’d like some kid to enjoy it without being part of some blues society. But I always parallel this with my need to be known as some sort of original performer.

“I suppose something has percolated down, but if a 15-year-old kid wants to enjoy it, I don’t want it to get to the point of being a music lesson... If you don’t go a bit crazy, enjoy the rhythm, keep the soul-beat and blend other things in properly, the music will become like the blues club clique, going up and hearing white guys doing 12 numbers by Freddie King. I wouldn’t want that.”

So you’re happy with the people who just let off steam in the front row?

Advertisement

“Yeah,” he answers but then hesitates. “Well, I wouldn’t go quite as far as that. I think it’s quite fair if at 18 you want to go out, get crazy and enjoy the music. But not mindlessly. As long as they know that the guy who’s driving the bus knows what he’s doing, I don’t mind them freaking out. But I’d hope they’d go home and say ‘what’s so interesting about this?’ – and check it out a bit more.”

Rory Gallagher’s return takes place after a changing of the guard. From the mid-’70s, he shared an Irish dual monarchy with Thin Lizzy. Now U2 are the presiding royalty and Phil Lynott lies in Sutton cemetry. How did that death affect him?

“I liked the guy,” he says, “but I was more shocked than I thought I would have been at his death, particularly with the long drawn-out hospital reports. I thought, now he’ll get through – but then he didn’t. I saw him a few months before, hanging out with Grand Slam, buying clothes or whatever. Then I saw him on TV with Gary Moore and I got a shock when I saw him. Not the appearance but something in his eyes, God rest and save him. You’d assume because of the reputation, inverted commas, you’d take it as just another one – but it shocked me more than I thought it shocked a lot of people.”

Gallagher survives and you can easily intuit the singlemindedness in his character – but even he now partially concedes time could be gaining on him, recognising he doesn’t retain all his youthful resilience. The road can be a demanding spouse for someone who’s poured all his energies into his gypsy vocation.

“I used to gallantly say – what’s good enough for Muddy Waters is good enough for me, I’ll play till I’m 62, 65, whenever. I intend to do that – but you do start learning. You think it’s going to be a breeze but it’s quite an undertaking (laughs). I’d rather go crazy on the road rather than off it – because it’s one or the other. I don’t know. If I could only be the relaxed type of musician, then I’d be much healthier because I could switch off for a night or go off for a holiday. You know every so often a person will ask me, ‘Rory, why do you get so intense on stage?’ and any time I try, not to lay back but to switch down, I just... it’s something I’ve got to watch.

“My dream would be to be fit and healthy at 65 and still playing, but that’s asking too much of the man upstairs, it really is.”

He accepts the existence of a nervous, terrier, obsessional quality within his psyche: “It’s fine to have free time. One failure I’ve always had is that I don’t plan free time. I don’t take holidays in the sun because so many prospects get delayed. So I might have had free time – but it was more agony free time. It wasn’t sitting on a beach getting healthy.”

Advertisement

He’s talking about those five years again ...

“Another person could give you a better overview. Life was going on. We were still doing festivals, rewriting, recording and so on. But I’m still trying to get over the workaholic thing because it is bad for you. Like I don’t take vitamin pills and all that stuff. But I got through it.”

Hot Press photographer Colm Henry wanders into the office. After their photo session, the expert fisherman comments of Rory, “He’s quite a deep character.” And it’s true. Cork, the Blues and 20 years nervous on the road – Rory Gallagher is all of a piece, a McAlpine’s fusilier who rejected the conventional wisdom to find his own romance between the airwaves and lost highways, when those dreams meant so much more than Ireland’s spinsterish isolation.

Doubtless pop’s recent neoconservatives could find his values fatuous but Rory Gallagher is about Irish values of honourable toil, of loyalty, of dedication and of supreme craftsmanship. He made his choices, he didn’t complain.

He’s lived it beyond the rhetoric and hype. Hardcore types might give Rory Gallagher a second view. Global glam games continue. Meantime, in 1988, a man who prefers his movies in black’n’white finishes: “I never blended in with the Led Zeppelin situation. Or even the Thin Lizzy situation or whoever you care to mention. Anyone who knows me knows what the origins of the music are. Though I’m not St Francis, l don’t make an easy path for myself. When I’m 65, I might say you silly fool, you could have saved yourself all that anxiety.”

But things either feel right or they don’t.

“That’s it.”

Advertisement

The legendary Hot Press writer, Bill Graham, died less than a year after Rory Gallagher, in May 1996.

Revisit Defender below: