- Music

- 14 Oct 20

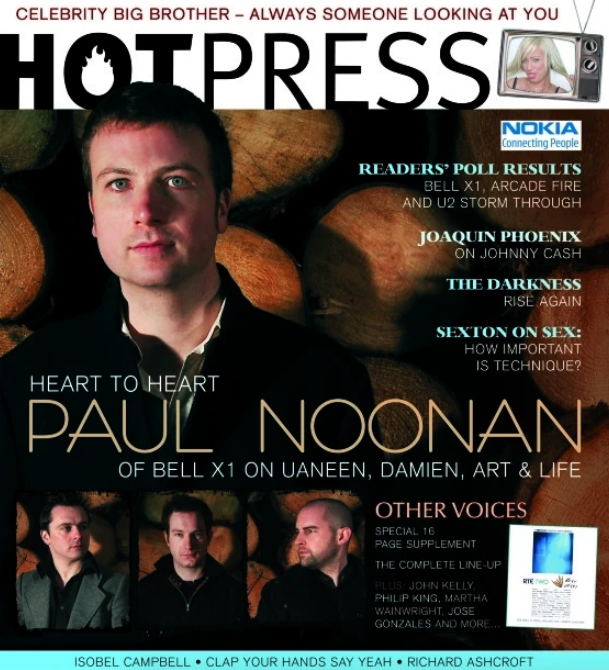

15 years ago today, Bell X1 released their third studio album, Flock – which scored the band their first ever No.1 on the Irish Albums Chart. To mark the occasion, we're revisiting a classic Flock-era interview with Paul Noonan.

With the release of their acclaimed third album Flock, which went straight to No.1 in Ireland, Bell X1 have staked their claim not just to greatness, but also to potential world domination – a possibility which is reinforced considerably by their powerful showing in the Hot Press Readers’ Poll. Here, in an emotional and revealing interview, the band’s photogenic frontman Paul Noonan discusses life, art, love, death... and music.

This conversation took place in the almost confessional hush of a tearoom in Dublin’s Merrion Hotel.

Moments after it ended, Paul Noonan, the frontman of Bell X1, still seemed fazed by the process – and the honesty he had shown throughout. “I’ve never really talked about Uaneen like that before,” he said, referring to Uaneen Fitzsimons, the much loved No Disco presenter and 2FM DJ, who died tragically in a car crash five years ago. Fitzsimons was just 29 years old and she was Noonan’s girlfriend when she died. Those who knew her talk about a wonderfully warm, generous and vivacious person, whose loss was acutely felt by fans of alternative music all over Ireland.

What has this to do with Bell X1, or with the band’s acclaimed new album, Flock – the record that raced to No.1 in the Irish charts, and is now poised to turn them into international stars? And has it impinged at all on the rise and rise of the band, which has seen them eclipse even the likes of The Frames in the Hot Press Readers Poll?

Advertisement

There is no doubt that the experience of grief of this kind has been a significant factor in colouring Paul Noonan's lyrics, and by extension Bell X1's sound. Two songs on the band’s last album, Music In Mouth, were specifically about Uaneen. Yet Noonan has, until this interview, never openly discussed the issue. There is a bittersweet edge to Bell X1's epic, yearning sound. But what of the man who carries the greatest weight in terms of shaping the Bell X1 ouvre? I could only try to find out what makes him what he is, by asking the questions...

Joe Jackson: So Paul are you the kind of “cute hoor” you refer to in ‘Reacharound’, the opening song on Flock?

Paul Noonan: I suppose I am, in ways. I think we all are because it’s ingrained in the Irish psyche.

But like the song says, are you yourself one of those babies who was kissed by “cute hoors in the corridors of power” – meaning politicians – and did that leave its psychic mark?

I would have been, yeah, and it probably did. Though I can’t actually remember being kissed by a politician, thank God. Yet I am from Lucan and I do remember friends of mine started the Liffey Valley Awareness group. One year they set up a stand outside mass in the run-up to the elections. Liam Lawlor would have been one of the politicians doing a lot of canvassing after mass at the time. There was a scandal or, at least, talk about planning and the fact that so much of the Liffey Valley was being rezoned. But my friends set up that stall, with a map of the area and the proposed rezoning, and during one of the masses these lads started tearing down the stall. It struck us even then that they must have been paid to do so, or asked to do so, by somebody. I would have been 15 at the time.

Did that experience kick-start the process of cynicism that is evident in ‘Reacharound’, or did you develop a broader view?

No, I would have developed a broader view and I am interested in Irish politics. But there definitely is cynicism in ‘Reacharound’. I like to think of such songs as snapshots of a certain time, or emotion. I hadn't necessarily a stance on any particular issue.

So what, to you, is ‘Reacharound’ a snapshot of?

What I see as the curdling of the Irish charm, with us being part of the generation of First World Ireland. I really have become very interested in the nature of Irish-ness and what it actually means nowadays because it has changed so much, so quickly.

Looking back to pre-Celtic Tiger Ireland is also a subject you explored in ‘Still Selling Shoes’.

Yeah, that is a more flippant take on this and it started with the line about a time ‘when Rory played the blues and Ronan was still selling shoes’. It seemed too delicious not to use. Though I’ve nothing against Ronan Keating, necessarily.

Advertisement

Many Irish rock fans wish he’d stayed selling shoes.

Well, yes. And maybe lines like that do capture a particular moment, though the pedants might say the two things weren't really ever happening at the same moment in time.

You were born in 1974. Your dad was headmaster at a local primary school and your family consisted of three younger sisters so – apart from the possible psychic rupture caused by being kissed by a politician as a kid! – would you say you had a healthy, balanced childhood?

Yeah. My upbringing was very balanced, although I am only now beginning to see my parents’ relationship as a relationship, rather than them just being my parents. In fact, I’m writing a lot about that these days and I think that, generationally, the kind of relationships people like my parents had are very different from what we have now.

No kind of family rupture?

In ways, I alienated myself from my sisters because I always did well in school and set the bar at a level they could never reach. I didn’t make it easy for them. An effect of that was that I was held in such high esteem by my folks – and that didn’t help matters.

So were you, at the time, insensitive to the pressure you were putting on your sisters?

I think so, yeah. In fact, I think I was oblivious to it until my late teens.

Yet you still remained educationally focused?

I did, I liked it. Though if I were to do things again, I wouldn’t have done engineering, which I did in college. Because I wanted to design stuff for Formula One teams. I loved the idea of working in a pit lane!

You got your wish in ways by naming your band Bell X1, after the first plane to break the sound barrier.

Yeah. But I’ve always had a fascination with technological invention and progress. The Bell X1 thing came from reading firstly, then seeing The Right Stuff.

Did you yourself ever have literary inclinations as a kid?

I certainly remember essays I’d written and being pulled up occasionally for plagiarising things I had read, like The Lawnmower Man by Stephen King.

Advertisement

You do still steal ideas. From songs, for songs.

I do, yeah.

As in, at least two on the new album. ‘Just Like Mr Benn’ opens with the lines “put your sweet fingers a little closer to the keyboard” which is a twist on the opening lines from ‘He’ll Have to Go’ – “Put your sweet lips a little closer to the phone”. And in ‘Flame’, you change Cohen’s line from ‘Hallelujah’, “you don’t really care for music do you?” to “you don’t really care for Jesus do you?” Own up!

So that country song is called ‘He’ll Have To Go’? I didn’t know that. But I was aware of the lines themselves and Cohen’s line. So both those references were totally conscious on my behalf. I particularly love Jeff Buckley’s version of ‘Halleluiah’, which – to me – is definitive. And I definitely wanted to ‘contemporise’ the “put your sweet lips a little closer to the phone” line, because my lines are directed to somebody who is in a far-away country and we’re in touch by email.

Is this the woman who you said somewhere you hope may one day come home to you?

Yeah. She will, if I don’t get too neurotic.

Many of your songs are deeply romantic. When did that tendency first manifest itself?

From the start, back when I was 17 and discovered girls. And that also is roughly when I started writing and found my voice. You see, I’d been to an all-boys school. So going to college at 17 was like being introduced to girls for the first time. That’s why my years at college, from 17 to 21, were really mind-opening in that sense.

And heart opening?

Very much so.

Before you found your own voice through writing, what songs or singers would have played that part for you?

Actually, at the time, I loved classic songs like ‘By The Time I Get To Phoenix’ and ‘Going Back’, because they would have been big at home, from my parents’ record collection. We used to even do ‘Going Back’ on stage.

Advertisement

Its theme of yearning for more innocent times also comes across, flippantly, or otherwise, in Bell X1 songs, ‘Still Selling Shoes’ for one. Carole King’s lyric obviously was pivotal to you.

It is a seminal song, yes. I was lucky that my folks loved that kind of music.

But what about music from nearer your own era? Talking Heads certainly seems to have been a huge influence on Bell X1.

Because I was the eldest in our family, I had no older siblings to introduce me to that kind of music. It was the older siblings of friends who made me aware of the likes of Talking Heads and Springsteen. In fact, the first Springsteen record I was introduced to was Born in The USA, which is often derided as bombastic. But even though I can see that side of it now, what was more important to me back then was being excited by music for the first time, by that record.

Some might see ‘Born in the USA’ as not just bombastic but as a kind of cock-rock. Is it really that surprising you loved it at the time? After all, weren’t you the kid getting the embarrassing hard-on at dances and scaring at least some girls away. At least that's the picture you paint in ‘Slow Set’ (from the Neither Am I album).

(Enthusiastically and smiling) Yeah, yeah, that’s right.

Do you now think that maybe Brucie played a part in your sexual awakening?

Maybe that is one of things that hooked me to Springsteen. Although I never thought of it that way. This, again, is something you only rationalise later in life. But I definitely remember, back when I was in sixth year at school, we’d go to a dance at a hotel in Leixlip called The Springfield Hotel. There’d be the mineral bar and a slow set three times a night. It almost harked backed to the time when my parents met and danced to the music of the showbands.

Going Back again.

Yeah, I guess so. But I really loved the frisson of it all. The excitement of asking someone to dance.

You were a clever kid, Paul. Isn't it true you moved in on the girls when your mates moved out of the room after the slow sets had started?

Yeah. Then came the occasional, but still embarrassing, hard-on. What I’m actually focusing more on in Slow Set is the embarrassment you felt when a girl was rescued by her friends. Girls have this coded way of getting a friend away from a guy. Like they say, ‘so-and-so is sick in the bathroom’ or whatever.

It’s easy for you to smile at that kind of memory now. Back then, presumably you would have been hurt when that happened?

Hugely. And it is a harsh landscape at that age.

Advertisement

That landscape can also be made transcendent when you fall in love for the first time. When did that first happen for you?

Nineteen, at college.

Did it last?

It has done, yeah. Though we’re not together.

Is this the woman who may come back to you if you become less neurotic?

(Fumbles) Yes, but I’m happy where I am. I’m not pining for that.

How long is this woman living in a far away country?

About four years.

But you obviously were involved with other women?

Yes.

Uaneen, for example?

Yes.

How did she fit into the equation, if you had this long-time love affair?

(Pause) That woman and I broke up a long time ago. But we stay close. And, sadly, Uaneen and I were only together for a short time, maybe two, three months. So we were very much still in the skittish, excited phase of new love when she died in that accident.

Advertisement

You once sang a very moving song for Uaneen at a Hot Press Awards.

That was ‘In Every Sunflower’ from the last album.

Any songs about her on Flock?

(Pause) Uaneen had a huge influence on my life and it is something I’ve absorbed and it has become part of me. Having that experience often seems to come through in my writing. But there is nothing specific on this album, no.

I suspect that Uaneen’s influence comes through specifically in the sense that she loved, and lived for, music, that you both breathed music together. Certainly in a track like ‘My First Born For A Song’ from Flock, you celebrate music itself. So was that one of the core connectives between you and Uaneen?

Absolutely. But the last record, Music In Mouth, even more specifically, was very much about those kinds of feelings. I definitely did want the mood of the record to be celebratory as opposed to dark or morose.

Why? Because that’s what Uaneen would have preferred?

I must admit I have very ambivalent feelings about all this. As I said, we were only in that young phase of the relationship when she died. What I really wanted was to make sure that I hung onto to what was real and not let the drama and the wrenching of what happened carry me away into overstating what I was and making career capital out of it.

So would you have seen it as vulgar or violatory to make career capital out of either Uaneen’s death or your relationship with her?

Absolutely. And I suppose I was even paranoid about that immediately afterwards because I felt that, publicly, I had sort of been held up as something that, possibly, I wasn’t.

Meaning, in the media you were publicly described as her ‘great love’, ‘lover’ or whatever, at the time?

Not everywhere in the media, no. But there was a lot of that. And I think that at time like that there is a huge potential for emotional voyeurism and pornography, for want of a better word. That experience certainly made me acutely aware of that culture. I remember carrying the coffin from the church and seeing a bank of photographers outside the church and I just found that so offensive. Yet people somehow think that is an accepted part of what the media is supposed to present to people these days.

Advertisement

But, in contrast with all that, presumably Music In Mouth was intended to be true to the purity of the time you spent with Uaneen?

That wasn’t the definitive total of the record but I like to think that certain songs did, such as ‘In Every Sunflower’, and probably even moreso ‘I’ll See Your Heart and I’ll Raise You Mine’, which is more of a celebratory song. And I remember one night, while playing it, we ended up playing ‘Do You Realise’ by Flaming Lips towards the end. I love the band but I really love when he says “Do you realise that someday everybody we know will die/Yet all the more reason to celebrate life”. This wasn’t a conscious decision on our behalf. We just drifted from one song into the other, which seemed very fitting and telling, to me.

In that line, Flaming Lips could just as well be paraphrasing James Joyce who said something like “an awareness of death makes for a more voluptuous form of living”. Or Tennessee Williams who once said, “if the dead could say one word to the living it would be live,” so could both those sentiments also sum up your philosophy since Uaneen died?

Definitely. I was invigorated – perversely possibly – by Uaneen’s death. But that line by Tennessee Williams is great and I do think that it is what the dead would say to the living, if they could. Maybe they can.

And do you also believe that you live, at your best – as Uaneen would have wanted you to – through music?

I do, yeah. I probably have since I was 15, whatever.

Did Damien Rice leaving Juniper also hurt you at that core level?

It did, yes. Because fundamentally, at the time, I saw it as a rejection, as in him saying ‘I don’t want to work with you, I don’t feel you are good enough’. So overall I took it as a rejection of me and us, as people and as collaborators and as members of a band.

Had you yourself and Damien been close?

Yeah. We still are.

And you collaborated on songs?

Yeah. Some songs he’d bring to the band completed, and some songs I would bring to the band completed and other songs we’d work on together. Dave did as well.

But surely, as with the lessons you later took from Uaneen’s death, Damien leaving Juniper didn’t break the band. On the contrary it seems to have galvanised you – first into changing your name from Juniper to Bell X1, and also redefining your music and starting out all over again in a way that has since become hugely successful. Meaning, even if you didn’t set out consciously to do it, you could have been thinking ‘fuck Damien, he may think we’re not good enough but let’s show the guy how wrong he is’.

Feelings like that were part of it, yeah. In fact, for the band and for Damien, the idea that either of us would fade away into anonymity was something we fought against.

Advertisement

Damien wasn’t really afraid of that, was he?

I think a big driving force in his success was his determination to prove that he could do it, as it is with us.

But can you now accept that he obviously felt he could only achieve that goal by going solo?

With hindsight, yes. I think it wasn’t necessarily us. It was more the environment in which we found ourselves. As in, putting out two songs we weren’t particularly into, not getting to make a record, being part of a circus. My one regret still is that Juniper didn’t make a record because I think we would have made a great record.

But Bell X1 has gone on to make increasingly greater records and that must be immensely gratifying?

It is. But I often worry about losing fire. Because I’ve seen people I would have loved back in their day losing it. I was a huge Police fan and really don’t like what Sting does now. And I was a huge fan of U2 and while I’m a still a huge fan of Bono and think he uses his position really well, I don’t like their music any more. I just feel it’s missing something, though I couldn’t tell you what that is. So I hope the fire that’s there now never goes from Bell X1.

‘Rocky Took A Lover’ on Flock focuses on a down-and-out who douses whatever fires were eating him alive, by drinking. Ever thus inclined?

John Power became a friend in the wake of Uaneen’s accident and that definitely was to dull the edges of the pain. But that sort of drinking only went on for a short time. I do remember when three of us were living in a house, where Rocky used to actually sit on the step and we’d watch him and think what a fine line there was between his life and ours and we’d wonder what it would take to push us over that line. Sadly, he’s dead now but I could never see myself going that extra distance, at all.

Do you think your sense of balance is rooted in the fact that you had a relatively secure upbringing during your most formative phase?

Definitely. And even in my post-school phase, it was a wide-eyed experience I had. I didn’t encounter darkness there at all.

Meaning, in part, you did drugs then?

Yeah. But the enriching experience was the people I met at that time.

Advertisement

And you never got heavily into drugs?

Not at all.

Not even for a short period, as with drinking?

No. No band I’ve been in has been Spinal Tap.

So does this mean you didn’t get into music for sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll.

No. And I actually think that’s an out-dated notion and that there are others reasons for getting into music.

Such as maybe your claim “history is written by winners and I want to have my say” – another of those great lines you ‘borrow’ and use in one of the songs on the new album, ‘Natalie’.

It is a great line, isn’t it? I don’t know who write that either. But, yeah, that would sum up what I would like to achieve. I said earlier that songs are snapshots, but albums can be too. Like Parklife, by Blur. I’m not a huge fan of the band, but that record really captures a particular period so well. And I’ve always wanted to be part of a band that had the effect bands like REM and later Radiohead had on me. Like, where I would take these records to bed with me and listen to them on my Walkman and become really invigorated, enlivened and inspired by the music. When I first heard REM’s Green or Life’s Sweet Pageant, for example, I was 15, 16, and starting to flirt with the idea of actually writing and they were very inspirational in that sense, urging me to do that. So I would really love an album like Flock to do that for somebody.

As in inspire some kid to create music?

Yeah, that, to me, would be ultimately the greatest reward, to have that effect as an artist.

That said, I’d hate to give out the idea through this interview that Paul Noonan is a singer/songwriter who just happens to have a band backing him. The music made by Bell X1 on, say, Flock clearly is collaborative and in many ways co-created by the entire band, right?

Absolutely. In fact, Flock is different from our two previous albums because it is less songwriter-in-bedroom-completes-song-brings-it-to-band and more about a-band-playing-in-a-room as the starting point. And Dave brings in lyrics. That said for most of the songs I’ve written I would have provided the lyrics complete. I certainly brought in ‘Reacharound’ and ‘Rocky Took A Lover’ complete, whereas something like 'Flame' was more collaborative. Though as I’ve said before, when we work together on songs we can interfere with things so much we’ll probably go blind.

So you admit Bell X1 can be wankers.

Yeah. That’s why we always have a good stock of carrots handy!

Advertisement

More seriously, the central song on Flock, as far as I can tell, is ‘My First Born For A Song’ if only because it does have that image of a songwriter locked away after midnight, in ‘a sea of Club-Milks, tea and ashtray’ – and probably John Power or whatever – trying to write a classic song. Where do you feel you and the band came closest to writing a classic?

I think we have written some great songs but I don’t think we’ve written a classic song that will become a hit and we all can live off for the rest of our lives.

That’s a different thing. ‘By The Time I Get To Phoenix’ was a classic hit but ‘Going Back’ wasn’t, it was more of a classic song that has seeped into the public consciousness over time. So the latter is more what I’m asking about?

Well, okay, then I feel it is quite rarely that we realised what we had set out to do. But some songs come closer to that ideal than others. Like ‘Rocky Took a Lover’ and, actually, ‘My First Born For A Song’, which is ironic, because it is, as you say, a song about the frustration of trying to create a classic song. But in ‘My First Born For A Song’ the music has resonance with the sentiment and it is, in fact, a more musically driven song than lyrically driven song and that, too is rare for us. And it is that kind of unification between words and music that defines a great song, isn’t it? Also, I’m a big fan of John McGahern and in a documentary recently I heard him say that we all have a personal world, that nobody else sees, and that the job of the writer is to throw light on that personal world and make it universal. That, in the end, is what I hope we do with our songs whether we, or anyone else, defines them as classic or not.