- Music

- 19 Aug 24

On August 19, 2005, Philip Lynott's native Dublin finally paid official tribute to his legacy by unveiling a statue on Harry Street. A huge crowd gathered for the event, which represented the culmination of many years of campaigning on the part of his mother, Philomena, and the Roisin Dubh Trust. To mark the occasion, we're revisiting Peter Murphy's reflections on the unveiling...

Originally published in Hot Press in 2005:

On August 19, the day before the late Phil Lynott’s birthday and memorial concert at The Point, a bronze statue of the musician will be unveiled outside Bruxelles bar on Dublin’s Harry Street, the result of a joint venture between the Roisín Dubh Trust, set up to promote his legacy over 10 years ago, and the City Council. One can only wonder what Lynott, equal parts rabble-rouser and proud patriot, would have made of it all.

“I’d say he would’ve fallen about laughing,” reckons Jim Fitzpatrick, a friend of Lynott’s since the early ‘70s, and a renowned artist whose elaborate Celtic mythological images adorned many of Lizzy’s iconic 1970s album sleeves.

“He probably would’ve felt it should’ve been on O’Connell Street beside Jim Larkin!”

If any Irish musician embodied the rock ‘n’ roll animal, it was Lynott. Van and Rory were purists in the best sense, but the Crumlin native was the first Irish musician to harness style as well as substance, a flash romantic and unashamed musical dilettante, whose cavalier attitude to pilfering the prevailing trends of any given age – from the hard rock of Lizzy to the reggae of ‘Solo In Soho’, from the elegiac folk of ‘Tribute To Dandy Denny’ to the synth pop of ‘Yellow Pearl’ – placed him with cherry pickers such as Bowie or Prince as much as craftsmen like Springsteen and Neil Young.

Advertisement

For a generation of young Irish males, whose avatars of cool had hitherto been writers, drinkers and actors like Behan, Harris or O’Toole, he was close to a folk hero.

Catholic but guilt-free, Dublin-born but black, hard-man and dandy, Lynott was a complex artist who understood the possibilities of myth, tapping into his audience’s residual post-adolescent fascination with cowboy yarns and horse operas, science fiction glamorama, Marvel comic strips and Celtic epics.

In common with Keith Richards, he graduated to rock ‘n’ roll via Saturday afternoon Roy Rogers and Hopalong Cassidy matinees.

To Lynott, performance was merely an extension of child’s play.

“Sometimes I go out there and go completely berserk – I’m often completely off me head,” he said in 1977. “And it’s got sweet fuck all to do with drugs. It’s just that I get as heavily into what I’m doing as when I used to be a kid playing cowboys. Anybody can be anybody in rock and roll. It allows for all these people to exist within it and live out their fantasies.”

Lynott, like so many musicians and actors, filled the hole in his own family history (he didn’t meet his father until his early 20s), with an invented persona.

Advertisement

“I think when you come from the background he came from, you have to invent your own character, because your character is informed by parents, your social environment,” proffers Jim Fitzpatrick. “And Philip was totally adept at that. Of course, he was a great reader in his early days. He sort of got lazy later, but he was very absorbed by Celtic mythology and Irish history. And when he met me, we were kindred spirits. He loved to hear the explanations of various myths and legends.”

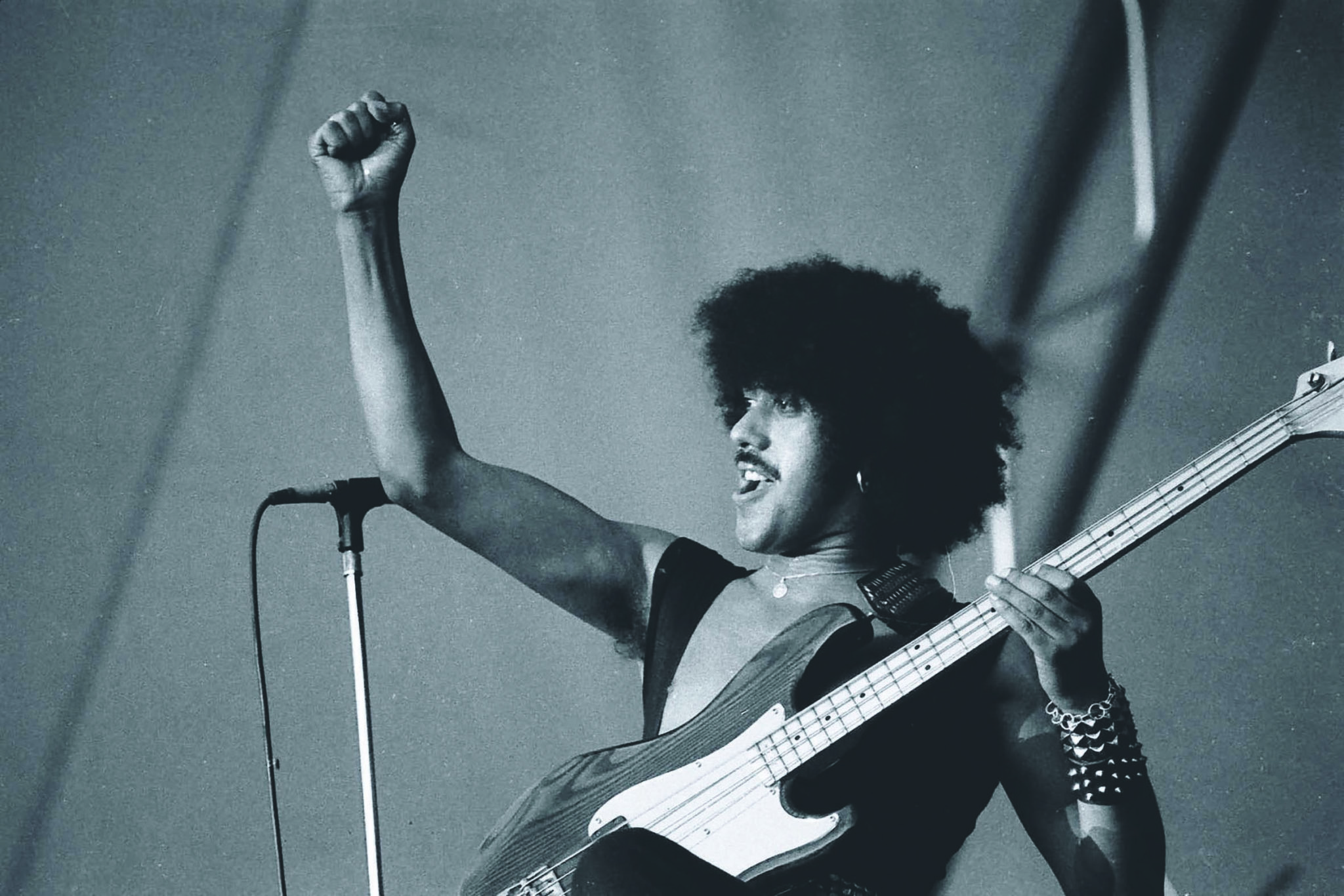

Too straight to play with the bi-boys, Bowie and Iggy and Lou, yet too silver-tongued to conform to Neanderthal metal stereotypes, Lynott cultivated an exotic image somewhere between Spanish Romeo, gypsy rogue and Southside Hendrix, replete with dangling earring, pencil-thin pimp ’tache and extravagant Afro.

If anything, his sartorial instincts had as much to do with Adam Ant and the New Romantics of the 1980s as with ‘60s figureheads such as Jimi and Keef.

“He was incredibly dressed,” enthuses Fitzpatrick. “I remember the two of us in the Dandelion Market trying on jeans, lying on the floor pulling them on. They were that tight. In those days if you had a big ass you were dead! But he was so snappy. Philip had the in-between bit between stylish and hippy that I couldn’t quite get.”

It is no exaggeration to say he was our Elvis Presley, Bill Graham observed in 1991. Certainly, Phil was both the snake-hipped pre-army Elvis and the drug-bloated Vegas self-parody.

Yet, according to Audrey O’Neill, director and secretary of the Rosín Dubh Trust, if there were murmurs of disquiet about erecting a monument to a man with a reputation as a hard drinker, drug-user and womaniser, she never heard them.

“I’m sure people have had their concerns and issues with it, but generally speaking, the council has been really behind the project,” she says. “Never has it come up about the darker side of Philip’s life, which I feel has all too often been glamorised in the media.”

Advertisement

But it must be said that, of all rock ‘n roll casualties, from Hendrix to Cobain, Parsons to Thunders, Lynott’s death was one of the least romanticised.

By the time he passed away in January 1986, Britain was in the grip of a new puritanism and tabloid-fuelled witch-hunt that claimed pop stars as apparently anodyne as Boy George.

The heroin-chic that afflicted Lynott associates like Sid Vicious and Johnny Thunders was long-since considered passé.

Jim Fitzpatrick sees Lynott’s drug addiction as yet another indication of the complexity of his character.

“You have to be a troubled person to take drugs,” he says. “You start off taking them for fun, but then to continue to the point where you’re actually going to die of it...”

The pressure of life in an iconic rock band put Lynott under huge strain, believes Fitzpatrick.

“He was a very independent sort of person, but how can you retain your own life when you have a band and an entourage totally dependent on you, one person?

Advertisement

“Like, he’d be devastated if he got a bloody cold, he used to just have to keep going through it. I remember when he had hepatitis many, many years ago and he had to cancel a lot of gigs and he was devastated."

Forced to live up to the popular perception of Thin Lizzy as hard living rockers, Lynott stumbled towards self-destruction.

“‘Lizzy got stuck in a groove created by expectations of the record company and the expectations of the punters who wanted more of the same, and really wanted them to be a hard rockin’ leather clad heavy metal band, and Philip felt totally hamstrung by that,” suggests Fitzpatrick.

“Add in the family responsibilities and you have a real case of extraordinary pressure. It’s a head wreck. I remember (Thin Lizzy road manager) Frank Murray telling me why he stopped managing The Pogues. He said, ‘I’m not gonna watch Shane die the way Phil did’.”

If the first casualty of war is the truth, then the first casualty incurred by posterity is complexity.

In the rush to set Lynott in stone, to ossify and fossilise him, subtleties and paradoxes often get dismissed as anomalous rather than integral.

Advertisement

Thin Lizzy’s legacy has a tendency to take on the cast of a heavy rock cartoon, partly because latter day albums such as Renegade and Thunder & Lightning and the desultory Life were hard rock by numbers.

Nonetheless, early-to-mid period Lizzy albums remain fascinating grab-bags of sounds and styles, lyrical ballads such as ‘Diddy Levine’, ‘Dublin’, and perhaps Lynott’s finest early song ‘Randolph’s Tango’, which combined Van’s lyricism with a Mink De Ville-ian Latin street punk serenade by way of Bruce’s ‘Incident On 57th St’. Indeed, Lynott and Springsteen seemed to shadow each other throughout the mid ‘70s, with ongoing dialogues taking place between ‘Born To Run’ and ‘The Boys Are Back In Town’, ‘Rosalita’ and ‘Rosalie’.

Before his creative arteries hardened from metal poisoning, Lynott was a conscientious and complicated songwriter, and even wild-rover ballads like ‘Cowboy Song’, ‘Wild One’ and ‘Southbound’ were tainted with melancholy. When Thin Lizzy played their last stand on September 4, 1983 in Nuremberg (their final Irish show had taken place at the RDS some months earlier, a pitifully sluggish affair), it was not ‘The Rocker’ that served as their swansong, but the long slow burn of ‘Still In Love With You’.

“They really worked it hard in ’83,” says Lynott fan, former Black Flag singer and post-punk renaissance man Henry Rollins. “There’s a ton of bootlegs from that last tour and you can tell the band in a way was coming apart.”

Lizzy played really fast in their final days – too fast, feels Rollins.

“That’s either a band too high to notice or wanting to get it over with and get back to what they were doing before, getting loaded.”

Advertisement

Listen carefully to those crackling bootlegs and you will hear a group of musicians trying to escape from themselves, he says.

“They’re opening with ‘Thunder & Lightning’ and it’s like, ‘Phil, if you slow down, we can hear what you’re saying’.”

You know the bell has tolled, says Rollins, when a band can’t wait to get off stage.

“Not putting the guy down, but it’s a band that had run its course. I’ve been in line-ups with bands, where there’s that tour and you know it’s the last one. You’re on stage with these people where the tension is brutal. The last Black Flag tour was very tense, not everyone got along. You can hear it in the playing.”

Since Lizzy’s demise, even the keepers of the band’s flame have tended to sell Lynott short as an artist.

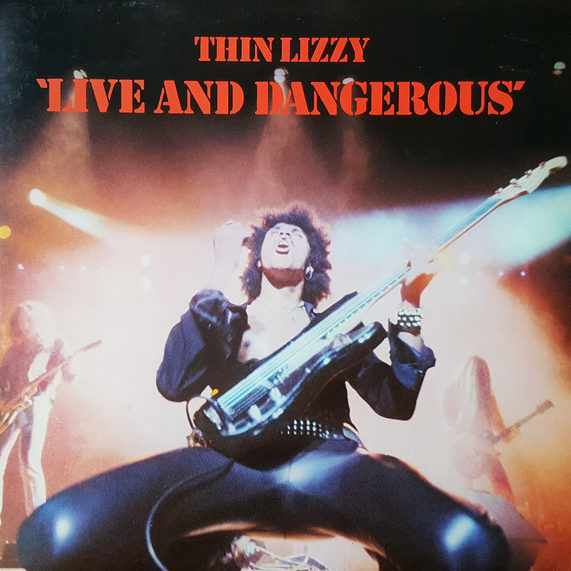

We’ve had too many tribute acts rendering Live And Dangerous as base metal; too many cash-in compilations; too many memorial concerts that tugged forelock to MOR metal acts not fit to lick Lynott’s winkle-pickers (Bon Jovi, Def Leppard), or joke rock acts (The Darkness).

One of the great mysteries of Irish music is that so few rock bands since U2 have taken up the Lizzy mantle. Only Downpatrick’s Ash have come close to reconciling the band’s marriage of hard rock and melody.

Advertisement

“When all the punks were hating all the rock bands, they seemed to accept Lizzy,” says Ash frontman Tim Wheeler. “I guess they just had this similar hedonistic attitude.”

He recalls a story, relayed by Thin Lizzy guitarist Brian Robertson (who also played in Motörhead), about a Lizzy party disrupted by the Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious.

“Robertson just got his clog off and went for him – ‘cos he used to wear these clogs he got in Holland – and whacked him over the head. Sid ended up at the end of the night crying in his lap. They were like best mates.”

Despite such skirmishes, Lizzy were one of the few hard rock acts that survived the punk fatwa (it didn’t hurt that Lynott had recorded with ex-Pistols Cook and Jones, The Damned’s Rat Scabies and Johnny Thunders).

“Why did punk rockers have time for them? I think ’cos Phil had time for punk rock,” says Rollins.

Punks could be precious about their scene, but they recognised Lynott as a ‘bad-ass’ of the first rank. In addition, his friendship with the Sex Pistols, The Damned and Motörhead protected him from derision.

Lizzy were also a hard rock act that acknowledged black roots other than the blues, qualities that tend to get ignored by much of their modern fanbase.

Advertisement

History freeze-frames Lynott on the cover of Live And Dangerous, leather-jeaned and punching the air. It’s certainly an iconic image, but there was more to the man.

“He’s gone from being multi-dimensional and multi-ethnic to being one dimensional, almost like a statue himself,” declares Jim Fitzpatrick.

Lynott was, he continues “extraordinarily complicated”, while giving the impression of being one dimensional.

“He kind of gave a caricature image of himself to the public because it saved going into the more hostile territory of the psyche. And in Phil’s case it was hostile, in that he had his own inner demons to deal with.”.

Even today, Fitzpatrick is loathe to discuss these ‘demons’ at length.

“I now feel reluctant to talk about them because he did confide a lot in me. We came from similar backgrounds in the sense that he felt abandoned by his father. We grew up in tough parts of Dublin, tough areas in those days to be either a redhead or a black man."

Advertisement

From the start, Lynott was determined to follow his own artistic path and not blindly submit to record company demands. The single ‘Randolph’s Tango’, released in the wake of ‘Whisky In The Jar’, was, says Fitzpatrick, a case in point.

“He went against all the advice of the record company and everybody who said to him what he should be doing. I remember a friend suggesting he should do a rocked up version of ‘Waxie’s Dargle’, and I remember the look on Philip’s face, because it was a good idea, but it was so far away from what he wanted to do.”

He may even have regretted ‘Whisky In the Jar’, Fitzpatrick believes.

“He loved (traditional singer) Luke Kelly. That was the reason he did it. But he didn’t want to be a rock version of Luke Kelly. He was afraid of that. And he came out with this left field, beautifully melodic piece of work. It got loads of airplay, but the people who wanted more ‘Whisky In The Jar’ didn’t get it.”

The relative failure of ‘Randolph’s Tango’ was a cross-roads for Thin Lizzy, says Fitzpatrick.

“That’s where the division began and the music became slightly schizophrenic and Philip ended up having to deal with it. Most musicians give their fans what they want, but true musicians stick to their craft, and that’s what Philip tried to do, long term.”

Advertisement

Fast forward to Fatalistic Attitude, his second solo album. Fitzpatrick considers it “an amazing piece of work”, but it left the record company cold.

“Philip was a charismatic character, but he didn’t see himself as just Irish, he saw himself as black, which was very important. If you look at his career after Lizzy, he started playing with an all-black band. In Bundoran, they played to an audience of 32 people. Philip was prepared to do stuff like that in order to just keep going on his own terms.”

Certainly, when one considers that line up, which included bassist Jerome Rimson, guitarist Gus Isidore, plus Robbie Brennan on drums, one thinks of Hendrix looking for an exit from the hard rock straightjacket into soul and jazz with his Band Of Gypsies.

Similarly, Lizzy songs such as ‘Johnny The Fox’ had more to do with Sly, Isaac and Curtis Mayfield than the late ‘70s metal revivalists.

“Phil really wanted to stretch, by working with people like Midge Ure,” says Rollins. “He wanted to check out all the different types of music, and I don’t think he was able to do that with Thin Lizzy.”

A brief partnership with Huey Lewis – yes, Huey Lewis – yielded predictably mediocre results.

Advertisement

Rollins: “I mean you’ve heard the demos with Huey Lewis, right? And that stuff’s pretty awful, and that's probably why it stayed in that demo phase. Take that song ‘I’m Still Alive’ – the lyric is okay but the music is just a bad idea, everything that was bad about the ‘80s."

Like many icons of the ‘70s, Lynott struggled to come to terms with the decade that followed, Rollins feels. He attempted to reinvent himself by forming Grand Slam after Lizzy’s final gig. Yet, while his audience wanted to believe, the project never had the opportunity to reach fruition.

“The most interesting thing about those shows to me is the audience really having to work to get this new version of Phil,” presumes Rollins. “But, the songs were not completely there yet. He probably would’ve needed some demo time and the right musicians to find the formula, in order to integrate himself into a newer sound.”

Perhaps Lynott created a myth so powerful, he never managed to outgrow it. Yet for an artist who died at 36, he left an impressively varied and accomplished body of work.

“The crowds wanted Thin Lizzy, they wanted ‘The Boys Are Back In Town’, 'Whiskey In The Jar', ‘The Rocker’,” concludes Jim Fitzpatrick. “They wanted him in black leather, not the cool suits. But to be honest Philip looking cool in a suit was much more Philip than him in leather.”