- Music

- 13 Jun 24

On the first anniversary of Christy Dignam's death, we're revisiting a classic interview with the iconic Irish singer...

Originally published in Hot Press in 2016:

How can I protect you in this crazy world?

In the song, the next line says: It’s alright, it’s alright. But that’s hardly what Christy Dignam has been feeling. The lead singer with the quintessential Dublin band Aslan has battled with heroin addiction, terminal cancer and the resulting depression. So how come he is still able to smile?

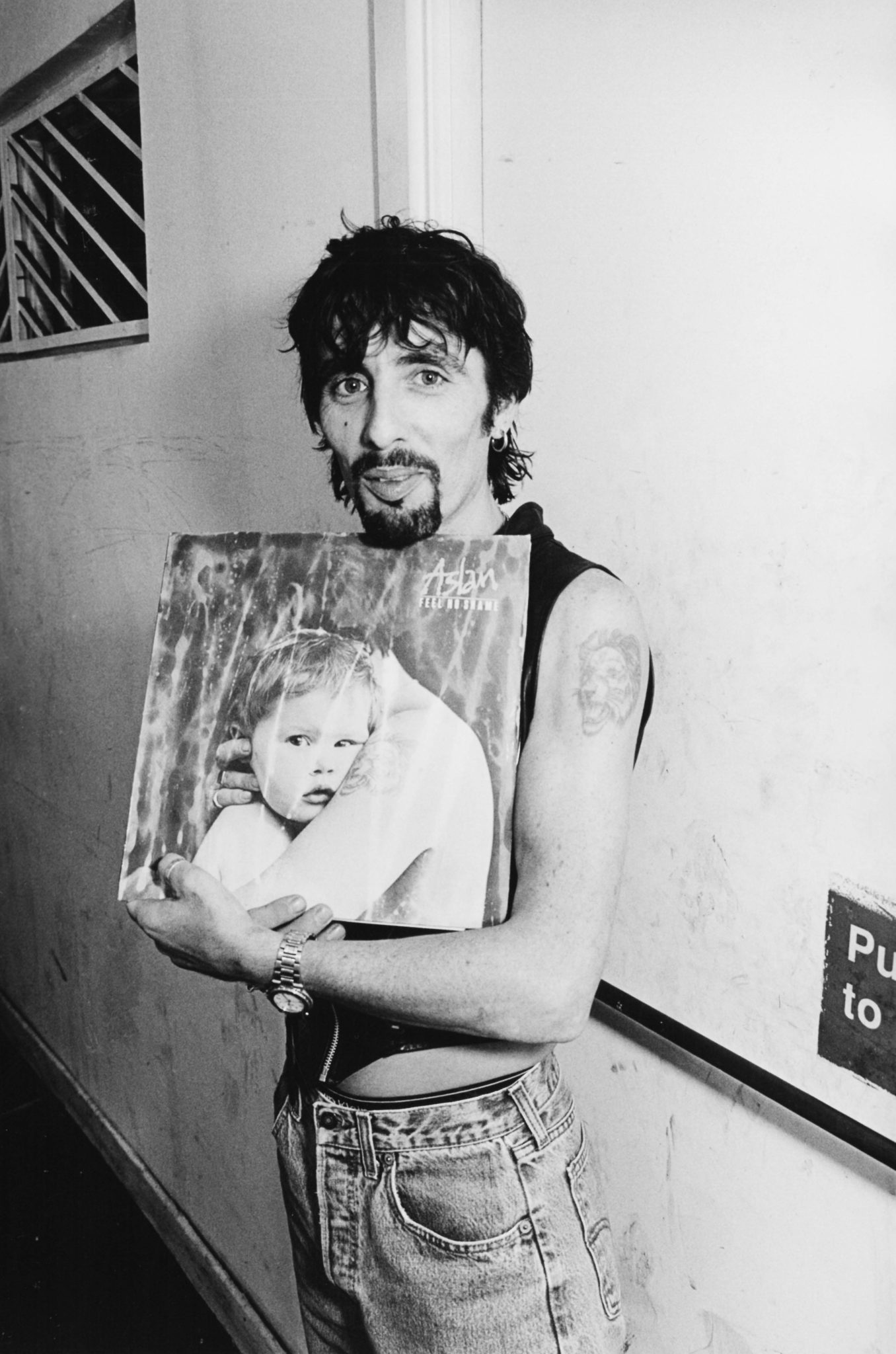

Christy Dignam has been a pivotal player in the Irish music scene since Aslan’s debut album, Feel No Shame, was released back in 1988.

As the 56-year-old singer admits, in this deeply personal and moving interview, the band – named after a character from The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe by C S Lewis – never fully realised their potential on the international scene. But Aslan have always held a special place in the hearts of Irish music fans. One of the great live bands, they have packed out venues all over the country for years. Along the way, Aslan broke up because of Christy Dignam’s widely publicised addiction to heroin. But they eventually put their differences behind them – and went on to release arguably one of the most popular songs in Irish pop history, ‘Crazy World’, as well as the critically acclaimed Made In Dublin DVD and album.

Advertisement

But, for all the band’s success, life has not been easy. A few years ago, Christy was diagnosed with a rare form of incurable cancer and there was a time when it seemed that he had only months, at most, to live.

A special tribute concert was held at the Olympia Theatre in 2013. Christy was undergoing chemotherapy at the time, in a wheelchair and unable to perform. A who’s who of the Irish music scene turned up to pay their respects and old Dublin rivals U2 recorded an electrifying version of Aslan’s ‘This Is,' which was played on the night and has since gone viral.

Still battling with the illness, the Finglas-born singer knows that, in all probability, he doesn’t have much time left on this earth. But he is doing his damnedest to remain upbeat, despite recent bouts of depression. What he has to say on that subject, and indeed about life and death issues in general, is surely worth hearing...

Jason O’Toole: I can imagine the tribute gig at the Olympia was a very poignant night for you. Normally, concerts like that are arranged posthumously.

Christy Dignam: It was surreal, but great. I always wanted to go to an Aslan gig to see what the punters saw. The band were playing with different singers, but at the same time, it was Aslan. So, that night because I wasn’t singing, I was able to judge the songs on a more objective basis. It was brilliant.

Did you cry?

Ah, yeah. At one point, I was fucking bawling. At the end I got up on stage and tried to sing ‘Crazy World’ and my voice was in bits. I was really ill at the time. I was still going through chemotherapy. So, I couldn’t sing.

U2 did a video for ‘This Is’ for the night, which has since gone viral.

I thought it was brilliant. I have to mention that Paul Brady was brilliant too.

Years ago you had an argument with Bono about ‘This Is’.

We went to him with the demo of that song for Mother Records. He wasn’t into it. At the time that caused a bit of a void between us and them for years. Thankfully, that’s fucking gone now.

Advertisement

But it pissed you off at the time?

Of course it did. I thought we epitomised everything Mother Records stood for, you know? We were a young Irish band trying to get a leg up who had been fucked around. We had been fucked around by record companies. So, I couldn’t understand it. I just think he didn’t see it at the time. In fairness to him, I think we might have given him a tape with three or four songs on it and ‘This Is’ was one of them. So, he mightn’t have even gotten through the songs. I wouldn’t say it was anything malicious.

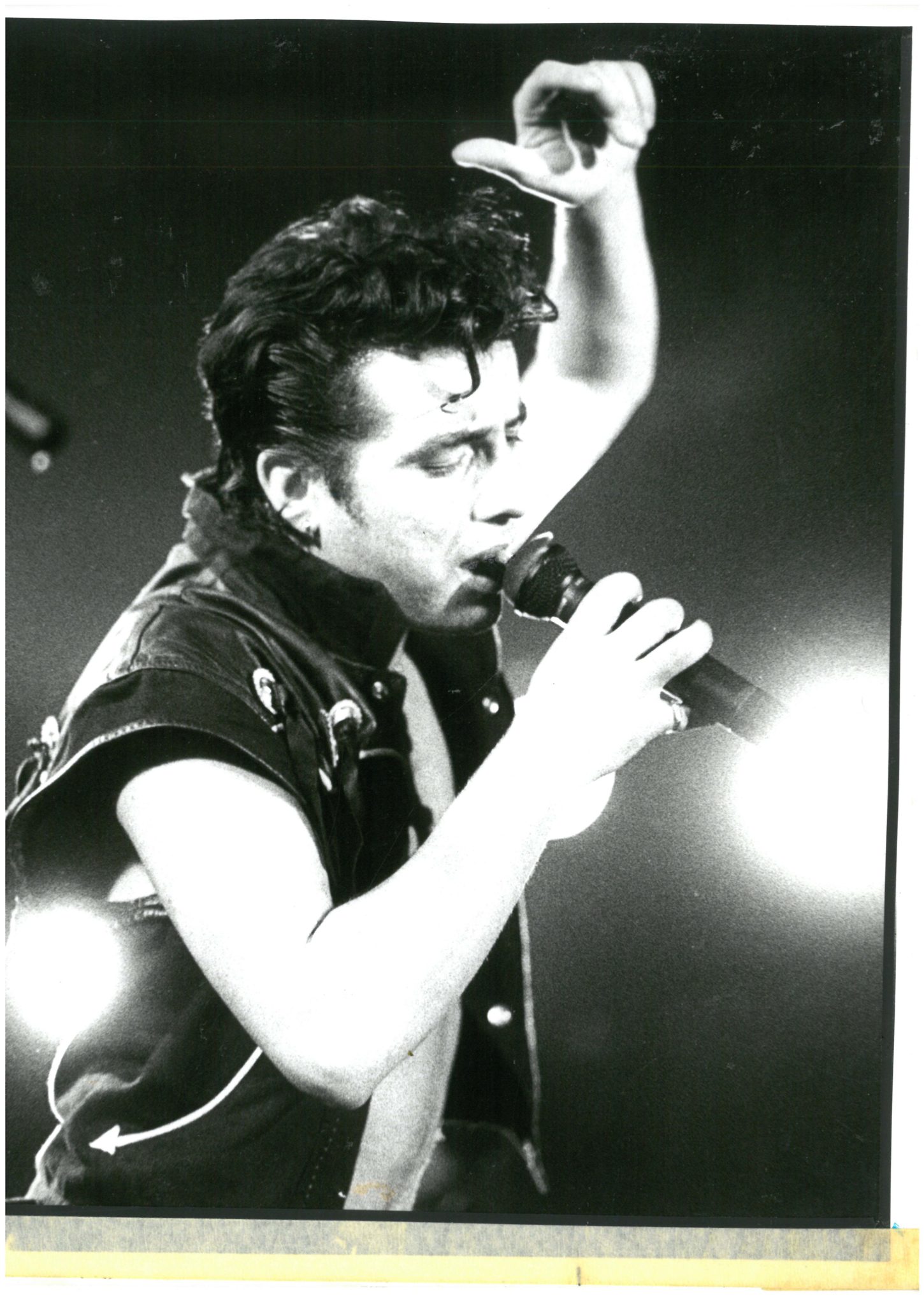

Aslan by Robbie Jones

You were both from the Finglas/Ballymun area. Was there rivalry as a result?

Yes, of course. When we were starting to break, I remember doing an interview with the NME and throughout it, we were asked, “Do you use the same rehearsal room as U2? Do you use the same studios as U2?” I got a pain in my bollix, so I wrote down Principle Management on a piece of paper and handed it to your man. And I said, “There you go”. I walked out of the interview. Your man called me back and apologised. And then I went into a little rant about being compared to U2. I said, “We’re fucking Aslan. We’re our own band”. I said something about, “Bono’s talking about Ballymun. People still have to live in those slums after he’s finishing glorifying it (with songs)”. The press picked up on it as, “U2 claim they’re from Dublin slums and newcomers Aslan set the record straight. Find out tomorrow in the NME”. That was the fucking headline. I was fucking mortified. U2 got onto us, “What’s all this? Badmouthing us in the media” – and it wasn’t meant like that at all.

But it must be great to put that completely behind you.

When I was in hospital, Bono wrote me a lovely letter. When I got out of the hospital, he came up to the house. He brought me a book of poetry by Seamus Heaney and his wife gave my wife a lovely present. And he was really cool, you know? I think he’s a wonderful person. He tries to do the right thing and he gets a lot of stick for it. I was very pleasantly surprised. I’m grateful that he came up.

Most music fans would’ve loved to have been a fly on the wall...

He was talking about the feeling you had when you were 18 and full of fucking venom and energy and you wanted to do all this. And he was saying, “There must be a way of getting back into that mentality. How would you suppose we could get back into that feeling?” The feeling he had when he was going over to London with Ali the first time with demos. We discussed that a lot.

What else did you guys chat about?

They were recording an album and I remember he ran out and got his iPad and came in and played me one of the songs from it. Things like that. We were just comparing notes. There’s not many people who would visit like that, 20-odd years after a huge public spat. He had every reason not to do that, because I had said some bad things about them over the years. It was really cool of him. I really admired that about him. Because the next day, I Iooked in the paper and he’s meeting fucking Michelle Obama (laughs). That was a great buzz. I thought he was lovely.

Advertisement

In some ways, it must’ve been therapeutic for you.

Yeah, absolutely. Because then when they were playing in the 3Arena, they asked me to get up to sing ‘Where The Streets Have No Name’, but I had a charity thing already arranged that night for two sick children, which I couldn’t cancel. So, they sent tickets for the next night for myself and my wife.

Bono changed the lyrics of ‘Angel of Harlem’ in your honour to: “Angel of Dublin / This one is for Christy Dignam/ Angel of Dublin/ What a voice/ What a voice/ What a voice.”

That was all lovely. It was really nice coming from somebody like him.

When did you first realise you were sick?

I had a gig and Kathryn my wife said, “Lookit, you can’t go out. You’re too fucking ill”. She rang an ambulance. I went from there – acting normally – to being in hospital. And then the whole thing took on a life of its own.

When did you first realise you had terminal cancer?

When I first got the news, I was very ill. So, I couldn’t fucking do anything. I couldn’t physically move because I was absolutely fucked. I was given 24 hours to live! The doctor didn’t say it to me, he said it to my family, that if I made it through the next 24 hours I had a chance. I was diagnosed on the Monday and on the Tuesday I started the chemo. The doctor said, “If he doesn’t respond to this, he has 24 hours at the most”. I only knew all that later on.

I read an article last year claiming you’d be lucky to make it to Christmas 2015.

That was true. At the time, they told me to get all my affairs in order. I had about six months at that stage, but I rallied. I responded positively to the treatment. But up to that point, they did say, “Get your affairs ready. You’ve about six months left”. The damage was extensive. It was a double whammy.

Undergoing chemotherapy must have been hell.

I’ll explain the situation. When you do the chemo, it kind of holds the amyloidosis (cancer) at bay – they reckon for about four years. So, then the cancer comes back and you have to go through the whole chemo thing again. But every time you do the chemo it’s a roll of the dice. Because it worked the last time doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to work this time. I try to not think about it. If I was to really think about it, I know I wouldn’t be able to get out of bed in the morning. What’s your life expectancy? There was three of us – me and two other people, both from Cork. We were diagnosed at the same time and we all went over to The Royal Street Hospital in London – and those two people are dead. I’m the only one left. It’s so under-researched: you don’t really know. The doctors don’t really know. When it comes back, I’ll have to go through chemo again. If it doesn’t work this time, you’re talking about months.

Advertisement

How much longer are you hoping to live for?

I’d like to get 10 more years, just to see my grandkids growing up a little. But, you know, like everybody else, Jason, you want as much as you can fucking get. Every day is precious. We play a gig, we do The Late Late Show, whatever the fucking thing is, and everything you do, you think, “This is probably the last time I’m going to do this”. You’re trying to absorb and really enjoy it. On All-Ireland Final Sunday I thought, “God! I might never see another All-Ireland”. It can be a bit torturous! It’s a rare condition. I go to the Royal Street Hospital in London twice a year and I do a thing called the sap scan where they inject a radioactive dye into my system and it photographs inside you.

How has the cancer affected you?

It was in my liver, it was in my spleen, my kidneys. It damaged my heart badly. At the moment, my heart probably works at two-thirds of its capacity. My bone marrow has a negative protein that attacks my organs and that’s the nature of the type of cancer I have. Nobody knows, Jason. Maybe the whole thing kicks off next year. It could happen next fucking week.

You’ve lost a lot of weight.

I went down to five stone. I was like a skeleton. But I’m kind of back up to where I was! Weight-wise, I’m grand. I’m actually getting a bit of a fat belly, which I don’t want.

According to media reports, you ended up in a coma in hospital.

Well, not really, no. You know, this one thing I remember now on the whole God thing, right? One night I was in hospital and I flatlined. And when I flatlined, I remember lying in the bed. I asked the nurse was I going to die and all that – this is when I kind of rallied a little bit. But while I was flatlined, I remember things happening in the room. They had put adrenaline into me to try to kick my heart back off again. Because it didn’t work the first time, they put more in. And I was asking the nurse about that and she said, “How did you know about that? Because you weren’t conscious when that happened!” I remembered thinking, “Maybe there is a God because what was all that about?” I was existing outside my physical being at that moment. Was it a case of seeing white lights and floating? Yeah. Do you remember them things years ago when you were a kid – you used to look through the kaleidoscope and see all the colours – it was kind of like that. There was a nice peaceful feeling about it. So, it was a bit fucking weird. So, that makes me wonder. I look at the complexity of the human brain and human mind and stuff and I wonder: just because the heart stops, does all that fucking disappear, you know? Sometimes I wonder. I haven’t worked it out yet.

Credit: Kathrin Baumbach

Have you come to terms with your illness?

I think I have. Obviously, nobody wants to fucking die! Everybody wants to stay here as long as they can. Well, most people. I’m no different. What I try and do – I don’t know whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing – but I just stick it in the back of my head and try (pauses)... There’s times I’m lying in bed at night and it comes to me and you start getting really fearful. So, part of me is terrified what’s going to happen to my family when I’m gone – all those things. But I try not to think about it because otherwise I’d drive myself fucking mental.

Advertisement

You suffered from depression: how bad did it get?

It got really, really bad. It got so I couldn’t get out of the chair. I couldn’t see the point of anything. It’s fucking horrible. I’d never been depressed before, not even through my addiction. Addiction knocks the balls out of you, but I never really got depressed. I didn’t even know I was depressed when that was happening. I didn’t know what it was. It was only when I really came out of it that I realised that it was fucking depression I was going through.

So how did you deal with that?

When I started recovering, I started feeling a bit stronger in myself. The tribute gig helped: I thought, “These songs are a lot better than I thought they were”. I never thought the songs were shit. But I didn’t realise how good they were: it was only when I looked at somebody else performing them with Aslan that I thought, “These really are fucking good songs”. Because I was able to enjoy it as a fan for the first time in my life. It was a very surreal experience, but I felt brilliant when I went home that night. That was probably the turning point because I was still going through the chemo and had felt really bad.

You were in a wheelchair.

Yeah, I could only walk a couple of yards. One of my ambitions was to walk my daughter down the aisle. She was getting married in June that year. That was a turning point too, because the first bit of walking I did was when we were in the Olympia that night.

Are you going to therapy?

I haven’t done anything like that, no. They do recommend that you go to a therapist. And if I felt I needed to, I would do it. It’s funny, when I first came out of hospital, I got really fucking depressed and started pondering my life’s work and all that, thinking, “I’ve done fuck all with my life?”

That’s a very strange thing to say, with your track record.

I was just in a dark place, you know? But I got out of it. I was thinking, in the big picture, what is it? It’s only music. I didn’t do anything profound and there’s kids starving all over the fucking world – and I just made fucking records! I don’t feel like that now. But, at that time, because I was so depressed, it was like that.

I heard people going through chemo can lose their memory.

I lost my memory and I couldn’t remember songs and stuff like that. Plus I thought I’d love to play at the tribute gig – but I couldn’t fucking sing. That was a huge shock to me. With the addiction, the one thing that saved me was that I was able to sing. I was able to get up on a stage and whatever demons I had, I could kind of exorcise them. But if that was taken away, I didn’t know how I was going to get through, you know what I mean?

So now, you take it day to day?

Absolutely. That’s the only way it can be now. Every day you wake up, you’re grateful that you’ve that day. And every night I go to bed, I think, “This is the last one”. You know, “Am I going to wake up in the morning?” It puts a lot of pressure on you. It’s exhausting. Even thinking like that is exhausting.

Advertisement

You’ve been with your wife Kathryn since you were about 15. How is she dealing with it?

She’s very strong. But you’d really have to ask her. I don’t know. She seems to be dealing with it really well. But she is a very strong woman.

Perhaps she’s putting on a brave face for you?

Probably. She didn’t say it to me, when they put a timeframe on how long I’d live. She was telling me later on that she was absolutely terrified. But I only found out when I didn’t die after six months! She said, “You know the doctors gave you six months”. She was praying that it wouldn’t happen to me. Because she lost her mother and father not so long ago. So, she knew the impact.

Have you made your funeral arrangements?

No. Fuck that! I thought about the cost of it, and I’m kind of concerned about that. I try not to think about it, to be honest with you. That’s for somebody else to deal with.

You briefly mentioned the possibility of God earlier. But I’m getting the impression you don’t believe in heaven or hell. Do you think death is the end?

Yes, more or less. I think so, yeah. Unfortunately. I think there’s a spiritual element within us. I don’t know how that will manifest itself after we die. I don’t know whether that’s just a thing to stop us killing each other while we’re here on earth. I don’t know really. But I’m spiritual. So, I believe in spiritual beings, you know?

Has facing death made you reconsider your views about God?

I was always very spiritual. When I got ill, I prayed a lot. But I have a bit of a problem with religion – because of the damage it does in the world. I’d love it to be the other way. I’d love to be wrong.

The general consensus amongst atheists seems to be that there’s this belief brainwashed into us, when really there’s no proof that there is a God.

It’s a very comforting thing. You know the way Karl Marx said it was the opium of the masses? I understand the logic in that because if people didn’t have religion, think about it? Think about old people living in this country in squalor. You know that saying about it’s easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than a rich man to enter heaven? People think, “I’m living in poverty here but I’ll have my day when I die”. A lot of shit you put up with in life, if there wasn’t a God – and that was proven – you actually wouldn’t put up with it. So, religion serves its purpose.

Advertisement

Even though you’re not religious, you said you prayed.

The big thing that terrifies me about dying is not the fact that I’m going to die and I’m going to leave this earth – it’s what the fuck happens next.

And, of course, leaving behind your wife and daughter and three grandkids...

I want to see them growing up. I love them to bits and I get on great with them. I spoil them rotten and I want to be there for them as long as I can.

Do you think your illness might have been related to your drug addiction?

No. I asked the doctor. I said, “Look, you know my past. It’s kind of well documented. Is this the reason I got this thing?” He said, “Absolutely not, 100%. This is a very rare condition. You know, probably only five or six people in the country have it at that moment. It’s just – say if there’s a God, God just pointed out five people and you’re one of them. It’s just one of those things”.

All the years you were taking heroin: how did your wife handle it?

We split up for about a year, where she just got a pain in her bollix with it. I don’t know how she put up with me – because I wouldn’t have put up with me! Would I have had the strength to put up with her, if she had of been the addict? I don’t know if I would have been able to. She’s an amazingly strong person.

How many years have you been off heroin?

Probably five years or six years. I was around 49 or 50.

Do you remember your last hit?

No. I fucking don’t – that’s funny. I look at people on The Late Late Show who gave up drink and they say, “I had my last drink on three o’clock on Friday 15th of June”. I never said this is going to be my last one. What happened was: I went to a methadone clinic and I was dabbling at the time, so I gradually stopped. So, I can’t remember the exact dates.

Advertisement

Do you still struggle with it?

No, not really. I’m cool now. I don’t really think about it anymore. As you get a bit older, you get a bit wiser. I have grandkids now, so they’re a great soberer, you know?

Where you afraid to take any medication to numb the pain in hospital for fear of ending up hooked on drugs again?

I was actually put on Xanax, but I wouldn’t take them because I was afraid of my past, that I’d get addicted.

Are you concerned about relapsing?

Listen, relapses happen. They happen for a reason. Any addiction is a relapsing disease. It’s a brain condition. They’re starting to realise now that this is not just a physical thing, it’s brain abnormality almost. It’s like a deficiency in the brain. So, that’s why people do that so much. People can feel guilty as shit. And I’d say: “Don’t do that. That will drag you back. Try not to get into that guilt thing”.

Was there a big drugs scene in Dublin when Aslan started out?

We were the first wave of people who got addicted in this country in the ‘80s. There was nobody before us. We didn’t have anybody to look at and say, “I’m not going to touch it because that’s what it does to you.” I bought into the whole sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll myth. I loved the whole Keith Richards vibe.

Aslan by Brendan Duffy.

Is that why you ended up on heroin?

There’s a couple of reasons. I think a lot of it has to do with the abuse thing. I wasn’t comfortable in my own skin.

Advertisement

You were abused several times.

When I was about six, this neighbour asked me to go up to the shops for a bottle of Coca-Cola and when I came back from the shop, his hall door was open. I knocked at the door and he said “Come on in.” I walked in and he shut and locked the door behind me. He stripped me, took all my clothes off, took the laces out of my shoes, tied me to a chair and then kind of did the business. He had me masturbating him and all that carry on. So, that was horrific. But I never felt anything for a couple of years.

What about the second time?

When I was about nine, it happened again with another neighbour. I told my best mate about it and he came out to me the next day and said, “I was talking to my brother about what happened to you and he wants to talk to you. He thinks he can help you.” So, I went in that night when his brother came home from work and his brother said to his younger brother, “You go downstairs, so I can talk to Christy,” and he did the same thing, more or less. It was abuse. I wasn’t penetrated.

Did you blame yourself?

I thought I had some hand in it. I thought there was something about me. I thought it was my fault. Because it completely fucks you up.

You’d secured a great deal with Aslan and recorded one of the best ever Irish rock albums, and it just didn’t click. Was it because of the drugs?

That has a lot to do with it, yeah. But we always fucked up with management. Bands coming along now have – you know that band from Cavan, The Strypes? There was a band years ago from Cavan called The Fireflies and the guitarist of The Fireflies is the father of the guitarist in The Strypes, so he managed them. So the point I’m making is: there’s a hierarchy now that can kind of support those bands now. But when we were coming to fruition there was nobody really ahead of us. We didn’t have that hierarchy of people that knew how to steer us through the business. So, we never really got a lucky break with managers. That had as much to do with it as the drugs.

The drugs really messed up the band.

There’s no way you can sustain an addiction without it having an affect on you. There were times when I should’ve been at rehearsals when I was running around looking for something. When you’re living with drugs, you’re sick. It was really fucking messy. There was a pool hall in Ballymun Towers and that was like a hub for all that activity. I did spend a lot of time in there.

Eventually, you were booted out of the band – and they got a new singer.

They had a song called ‘Strange Love’. I seen them on The Late Late Show and I was fucking delighted when I seen them because I just thought, “They’re fucking shit (laughs).” It would’ve killed me – being honest about it – if the singer had been great. So, when I seen how bad they were, I thought, “Lovely! They’re shit. They’re not going anywhere.”

When you got back together, did they stipulate that you had to stay off smack?

No, it wasn’t really mentioned.

Advertisement

How did you manage to write great songs like ‘This Is’ and ‘Crazy World’ while doing drugs?

I really don’t know (laughs)! It was just a love for it. I didn’t want to be just a good Irish band. I wanted to be a great band.

On the road, what was it like when you were touring the States?

It was mayhem. I was long married and I can’t really go into it. It was rock ‘n’ roll.

Lot of offers of groupies?

Absolutely, yeah. And some of those offers probably would have been taken up (laughs)! But, as I said, I can’t say who or when or what. Everybody was in relationships. But obviously we were young men. We were thrown into a situation that every kid dreams of. We were with Capitol Records at the time. Everything was going great. I remember driving down Sunset Boulevard and there were massive big posters with the cover of Feel No Shame on them. I remember going up to someone and saying, “Holy fuck man! This is cool.” And all the things that went with it. We were like every other band: we availed of what was happening.

Was there a lot of coke?

There was a rep who met us at each state you went to. So, the first rep was in New York – he bought us a couple of grams of coke and a few bottles of champagne. And then we got to Boston and the rep from Boston said, “How did fucking Johnny from New York treat you?” I said, “He was a mad bastard. He bought us three grams of cocaine and three bottles of champagne.” So, he went out and bought us five grams of cocaine and more bottles of champagne! So, we started playing one off the other. By the time we got to Los Angeles, it was fucking crazy.

Do you feel you’ve been underrated in Ireland?

I’ll be honest about it: I do. But, to me, you made the record and as soon as you made it and released it, it was out of your hands – and whatever happened after that is really in the lap of the Gods. One album I wasn’t thrilled with was For Some Strange Reason. Everything else – in a fair, just, world those albums would’ve been big.

When you first told the band about your terminal illness, what was their reaction?

Obviously, they were shocked. Billy said he always wondered what would kill the band. I think that was the first thing that came into his head: “Jaysus! This is the end of the band.” I don’t think he was concerned about me: he was only concerned about the band (laughs)!

Advertisement

Aslan by MIguel Ruiz

I’m guessing Aslan aren’t rolling in it.

I don’t have a pension or any of that carry on, so that concerns me a lot. We’re a working band. That’s what we do. That’s how we pay our mortgages – and we all still have mortgages and stuff.

When you pass away, I presume that will be the end of Aslan?

I couldn’t see it continuing. I don’t think they want to do it. I know Joe definitely wouldn’t want to do it. And Joe’s one of the main songwriters in Aslan.

Is the voice coming back?

Yeah, that’s back and I’m as good as I ever was. It’s even better because there’s more life experience in it. I think that gives it a bit of colour.

I understand the band is planning to recreate your famous Made In Dublin gig at Vicar St. this Christmas.

We’re doing 'Made In Dublin Revisited'. We’re going to play the whole album as it was recorded back in the day. We’ve got the same musicians, the same piano-player, the same strings that we had at the back of the stage – and we’ll replicate exactly as it was recorded in Vicar St.

Are you going to record new material?

I’m writing new stuff at the moment. We’re hoping to get something out next year. I want to have the swansong. That’s what we’re kind of about at the moment. We want to make it really special.

Advertisement

I presume the lyrics will be heavily influenced by the thought of death.

It would be like Bowie’s Blackstar (laughs). It won’t be that good! Obviously, it will be affected by the circumstances: I’ve always written about what’s going on at that particular time in my life and I don’t think this will be any different. Blackstar is a great album. He knew what was happening and where he was going. It shows you the class of the man. The way he ended his life was as profound as the way he exploded into the business in the first place. To me, it shows the strength of the artist.

Do you have any regrets in life?

No. I’m not into regrets. Regrets are ridiculous. They’re a fucking waste of time. They’re negative. I made decisions that if I had my life to live again that I mightn’t make. But all these things were a learning process and they brought me to where I am today and I’m quite happy where I am today.

Many years ago, you had a ghostwriter do your autobiography.

I’ve never read that book because I was always afraid to read it. It was too close to the bone.

Legacy-wise, how do you want to be remembered?

As a singer and songwriter in Ireland who helped elevate the quality of music in some small way. If I got that, I’d be happy enough.

• Following a decade-long struggle with illness, Christy Dignam passed away on June 13, 2023.