- Music

- 21 Sep 24

To mark what would have been Leonard Cohen's 90th birthday, we're revisiting a classic 1988 interview with the legendary artist...

Originally published in Hot Press in 1988:

“This is pure fantasy. Never heard of the man mentioned here.” This was the playful message Leonard Cohen wrote in the margin of a 1968 New York Times profile, when it was re-printed in the songbook The Songs Of Leonard Cohen. My own response was similar as I read the reviews of Cohen’s recent sell-out concerts in Dublin’s National Stadium.

All this talk about Cohen still being synonymous with bedsits, slit wrists and self-indulgent despair now really is ‘pure fantasy’. Indeed the pin-striped suited, synthesiser-playing Leonard Cohen we heard at the Stadium, with songs joyfully pulsing out through the new techno-pop arrangements, really is as far removed from the safari-suited singer/songwriter that first stood in the Stadium in 1972, as this issue of Hot Press is from that profile in the New York Times.

Though Leonard Cohen and Elvis Presley seem to occupy different time-zones in the history of rock, they were born within a year of each other. And Cohen, like Lennon, Dylan, Springsteen and so many others, vividly remembers the ‘shock of recognition’ he felt when he first heard Presley in the ’50s.

“I was relieved that all the stuff we’d been feeling for so long found expression in Presley and in rock in general,” he reflects now, “I was playing his records all the time to friends when they’d come over. I’d say, ‘This guy is a great singer’ – and they thought this was some kind of inverse snobbery. But it wasn’t. Presley had that special kind of voice which makes your heart go out to a singer.”

Advertisement

For different reasons, the same might be said of Cohen’s dark and atavistically resonant voice. His decidedly European style of sprechgesang (speech-song) does have its critics, and it’s a subject on which Cohen humorously mocks himself on his latest album: “I was born like this / I have no choice / I was born with / The gift of a golden voice.” But there’s no doubting the power of that rich, mature timbre.

His appeal isn’t purely lyrical. Cohen can rock too, as evidenced by howling versions of ‘Hallelujah’ and ‘There Is A War’ on the current tour.

“I can rock out, if the moment is right for it,” he says. “I can’t sell myself on that because I don’t have enough of that material, but I’ve loved it all my life, danced to it all my life. So no matter what some myopic critics might say, I don’t feel I have to justify my position in relation to rock. It’s my music as much as any other music is.”

And yet Cohen’s style of songwriting is more European than mainstream American, more Bertolt Brecht than Brill Building. “I learned my trade reading Lorca and listening to songs by people like Brecht,” he reflects. And these influences still show in his work. The lyric of ‘First We Take Manhattan’ is set against what he describes as a Sergio Leone soundtrack, which acts as a form of sneering counterpoint to one of the song’s main themes.

“If the lyric was set to something more solemn or ponderous it would have bored me to death!,” he laughs. “If it didn’t have that kind of techno-pop counter-point the song would collapse. But these things aren’t done from a point of view of strategies. They just evolve. Like that song grew out of one called ‘In Old Berlin’, half of which went off to become ‘Dance Me To The End Of Love’. And to get to where it is I had to go through five notebooks of maybe 50 verses, just slowly scratching away. I don’t have any strategies, even in my private life. Any I had collapsed years ago!”

Cohen may not have any strategies but, as a man who has been making music for nearly 40 years, he has a musician’s instinctual feel of what is right. One Dublin critic recently slammed ‘the soullessness’ of Cohen’s backing vocalists, missing the point that on emotional cuts, Cohen uses backing singers in the manner of Ray Charles (one of Cohen’s favourite singers). “I worked hard with Anjani, who does backing vocals, to get a flat bubble-gum quality to her lines,” he says, “something mindless and that’s done with precision and her intonation is perfect; it’s exactly what I wanted.”

Advertisement

Cohen’s approach is diametrically opposed to that of Jennifer Warnes, who had a mega-hit last year with an album of Cohen’s songs, Famous Blue Raincoat.

“She goes for real emotion in the back up vocals… her taste is impeccable, her musical decisions are impeccable. I’m very pleased with this project for many reasons. I love Jennifer as a person and as a singer and the fact that she’s dedicated all that talent to my songs – well you don’t have many of those gestures made towards you, in your life.”

Jennifer Warnes' success aside, Cohen’s profile has been helped recently by the interest in his work expressed by younger musicians like Matt Johnson, Coil, Bono and Nick Cave, among others. “People are also beginning to see I’m not and I never was a flower-child from the ’60s”, he laughs. “And that the work I’m doing now and have done over at least the last decade is considerably different from earlier material.”

And yet now, it is primarily Cohen’s words which seduce the listeners. He’d published four books of poetry before recording that first album and it’s essentially a poet’s sensibility he brings to his lyrics. But over the years the language in the songs, if not the poems, has become less surreal and less allusive.

Cohen talks now of wanting to strip the language ‘right down to the bone.’ “Well, you do find that there is only one way you can really speak. And it can drive you mad if you’re not speaking in your own voice. So, for example, a song like ‘I Can’t Forget’ – that started off as a religious hymn about the liberation of the soul.

“The metaphor was the exodus of the Hebrew children from the land of Egypt. I’d worked on the lyric over a number of years – but when I tried to sing the lyric I choked on it. It was a total lie in my mouth, because the theme was too ambitious. I don’t know anything about the liberation of the soul in that sense; it wasn’t true so I couldn’t sing it. So I had to get right back to zero and that is where the language on this album really began to gel. I started again at the bottom line: I stumbled out of bed – that was true. I got ready for the struggle – that is true. And now I am addressing that eternal struggle this way.”

Advertisement

Cohen’s commitment to singing ‘only what is true’ led to what he describes as “the ship-wrecking of many new songs on that very question of the singer needing to find the real voice and the real words to carry the voice.”

Because of this, recording the album turned out to be what he, only half-jokingly, refers to as “a very expensive exercise, very expensive.” Another struggle Cohen once had to confront was drug use – and abuse. His earliest encounters with chemicals came during the age of Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’.

“What I was after was a significant high,” he says now, “so during the ’50’s and ’60’s I tried everything I could get my hands on. But in time I found that this high became more available through other forms of activity. And the mind that is produced by certain kinds of study, certain kinds of discipline, is so much more finely-attuned to those areas you want to get the news from that, in the end, even using hashish is like treating a pocket watch with a sledgehammer. I wouldn’t go near drugs nowadays. Cigarettes are the only drugs I’m combating now.”

And yet a line of romantic writers from Ginsberg back to the time of Rousseau did believe that drugs could be an aid to creativity.

“It’s impossible to understand the ’60’s culture without addressing the question of lysergic and the position it played right through the decade,” he comments. “It was an element of my creative endeavours at the time, but I don’t believe it was in any way a decisive factor.”

Would Cohen agree that the imagery in some of the songs he and writers like Dylan produced ‘under the influence’ may have been inaccessible to people who chose not to experiment with drugs?

“I don’t think it’s necessary to love poetry to be a fine human being,” he reflects. “I think there is a lot of ways we can get our information that has nothing to do with art and if somebody can’t penetrate Dylan’s imagery or my imagery then let them knock it aside. Besides, one is not meant to understand the meaning in every song. Some work best if the listeners just sit back and allow themselves to be ravished by the material."

Advertisement

In his 1977 song ‘Death Of A Ladies’ Man’, Cohen wrote of a man who “is trying hard to get / a woman’s education / but he’s not a woman yet”.

“I think this was quite an insight into the sexual politics of the time,” he now says, “where we started to hear about or see a kind of feminised man. Or a man who could appreciate the woman’s position or could affirm the feminine aspects of his own nature. But despite being filled with good intentions, I am not one who believes in any kind of movement. Maybe it’s just my nasty, cantankerous, argumentative nature, but there is something about these ‘self-improvement’ rackets that turn me off. Like a concept of the ‘feminised’ man – because it suggested that we are going to transcend the dualistic and conflicting nature of life…”

And yet Cohen has said ‘there is a fundamental reality where there are no genitals.’ Likewise, a critic, after listening to Jennifer Warner interpret Cohen’s songs, said the experience convinced him that ‘the soul is genderless’. Does Cohen try to try to write from a point which is neither masculine nor feminine, yet is both?

“Well, you’ve got to move between these two points and take the residue of each point back to the others. If you never experience yourself as neither man nor woman or, for that matter, as neither fish nor any form of creature, then eventually you are going to get bored being just a man. When you jump into a pool of water you don’t hit that water as a man or a woman you hit it as shock; that is the central reality I was talking about back then.”

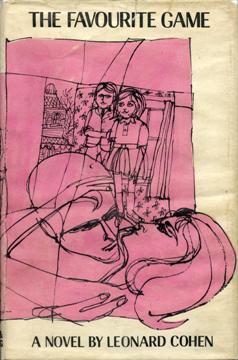

Cohen’s journey towards the soul of woman did take a rather predictable route in his youth. As one commentator said of his first novel The Favourite Game (1963), “Cohen seemed close to the salvation-through-sex mythos popular among Hemingway’s generation.”

“I do feel differently now," he says. "People have ways to reveal themselves to one another. Sexuality is one way but it is not the exclusive way. Maybe in The Favourite-Game, being an extremely randy young man, I played the whole hand on that particular card, but I don’t feel that way now.”

Advertisement

In her recently published book Intercourse, Andrea Dworkin said that many men try to reassert old positions of power through the sex-act.

“Well whether that’s true or not, the whole range of arguments in that book is quite radical and complex and beautiful,” Cohen says. “It’s the first book I’ve read by an author, masculine or feminine, that has a defiance of the situation, which is deeply subversive in the holy sense – it’s other-worldly. She says that this world is stained by human misconception, that men and women have wrong ideas – even if they are ten million years old and come from the mouth of god, they are still wrong! The position in that book is so defiant and passionate that she creates another reality and just might be able to manifest it. It’s from that kind of appetite, with the way things are that new worlds arise, so I have deep admiration for Andrea Dworkin.”

But mightn’t Andrea Dworkin also articulate an ‘unconditional declaration of dissatisfaction’ with Cohen and/or the kind of ladies’ man he seems to represent? Mightn’t she say he fed into those misconceptions?

“Sure, yes. But then I am ready to be swept away. I will be swept away, so nobody has to work too hard at it. The years will sweep me away and bury me as they do every man, so nobody need get too upset about my position.”

Cohen laughs, then pauses to light another cigarette, an element of sadness in his posture. “Of course she would find a lot of things in my work which would be incompatible with her position,” he adds, “but then so do I. I find that positions I now take are quite incompatible with those I once held.”

And yet, Cohen is quick to reject the perspective of those radical feminists who accuse him of blatant sexism. “Do you have an orifice and a pair of breasts? These are the essential if not sole requirements for a female character in a Leonard Cohen novel,” wrote one such critic.

“That’s a sad commentary on my work,” says Cohen, a little angrily, “because it places the most mechanical and dirty view on something that could equally be described as union or transcendence. If that’s what they think sex is, or see in my work, it says far more about them than it does about me.”

Advertisement

In The Favourite Game, Cohen’s prose certainly aspires towards transcendence: “Some women, Breavman thought, women like Shell create it (beauty) as they go along, changing not so much their faces as the air around them. They break down old rules of light and cannot be interpreted or compared…” But what about the argument that he fails women by denying them their human personalities, setting them up as only goddesses?

“I can’t see things that way either. I don’t think anybody has failed anybody else. It’s only when you walk around with a programme or a fixed ideology or a strategy that you really encounter failure in this respect.”

Have women lost the need for love (romantic or otherwise) from men?

“The evidence is that it hasn’t worked out well between men and women, but nobody can penetrate the need. That’s why I write 'There Ain’t No Cure For Love’. Nobody can tolerate the ache of separation, nobody can tolerate the vertigo of surrender. But that doesn’t mean we’re going to abandon the whole deal. We’re not going to. Everybody makes a continuing negotiation for a changing deal with love, because we need it so much. A deal with our children, mates, lovers, parents. As men and women.”

On the same theme, however, in ‘Everybody Knows’, Cohen sounds the death knell (in more ways then one) for the style of man – and woman – who does seek salvation through untrammelled sexual activity thus: “Everybody knows / that the naked man and woman/ just a shining artefact of the past.”

Advertisement

“That interpretation might be pushing things too far,” he reflects, “but certainly we do know that people will never lie down again with each other in our lifetime with the same sense of abandon that we have at this moment. The development of AIDS is the reason – but I tend to see AIDS as symptomatic of a deeper breakdown in our psychic immune system…”

Has AIDS affected Cohen’s sex life? “I’ve always made it an absolute point never to discuss my sex life.”

But hasn’t he discussed it in voluptuous (and profitable) detail in novels, songs and poems for nearly 30 years? “That’s not my sex life,” he counters. “It’s based on my experiences and the experiences I’ve studied in the lives of my friends. And when I write about it in a song, whatever I want to say about it, is there.”

“Several girls embraced me/Then I was embraced by men” – a line from one of his earliest songs, ‘Teachers’. Was the gay dimension part of the pattern of his exploring all points between the masculine and feminine poles?

“I don’t want to make a commentary on that or other songs. I never do. It says what it says,” he replies a little impatiently. “It’s not about homosexuality as such, but yes it is about the spirit, and whether it moves toward the sun or the moon.”

Has he moved in both directions?

“Yes.”

Advertisement

Does he now? “Those metaphors no longer have any meaning for me,” he says, drawing a distinct line….

Much of Leonard Cohen’s inspiration can be traced back to his religious training. “There is a power to tune into,” he reflects. “It’s easy for me to call that power God. Some find it difficult.”

He studied Zen Buddhism – though again he refuses to define himself in that specific religious sense.

“I never saw myself as a Zen Buddhist. In fact I was sitting with my old Zen teacher just before I left on this tour, we were having a drink together, and he looked at me and said, ‘Leonard eighteen years I know you, I never tried to give you my religion, I just poured you saki’. That started my relationship with Zen. I bumped into a guy that I liked, and I guess if he’d been a professor of physics at Heidelberg I’d have learned German and studied physics to communicate with him. I just saw him as a guy who had a handle on things that I hadn’t grasped yet, so it was appropriate for me to hang out with him.”

However the original point of reference for Leonard Cohen is that he was born a Jew.

“The point is that I don’t know what it is not to be Jewish so when people ask ‘do you define yourself in terms of Jewishness?’ such questions tend to have a fictional, irrelevant sound to them,” he explains. “I was brought up as a Jew just as I was brought up to believe I am a member of a hereditary priesthood and that I can give the ancient priestly benediction that binds the generations, one to another. That’s part of my legacy. And I was also brought up with a sense of time and of a people who have defined themselves as outside of time, to whom history has already happened.”

And yet history is an ongoing process. Cohen once said, “In any crisis in Israel I would be there.” Is that still true?

Advertisement

“Well, a saying I now have is ‘I can’t stand idly by my brother’s blood’. It’s not political as such but my feelings about this whole thing, if anybody really has the time or interest in what I think about the thing, is there in ‘Book Of Mercy’. And it’s in prayer… Israel, and you who call yourself Israel, and every nation chosen to be a nation, none of these lands is yours, all of you are thieves of holiness, all of you are at war with mercy… has Mercy made you wise? Will Ishmael declare, we are in debt forever? Therefore the lands belong to none of you, the borders do not hold. The law will never serve the lawless…”

And yet, irrespective of how timeless one hopes prayer or poetry can be, that book was published in 1984. Has Cohen’s perspective been in any way altered by what is happening in Israel today?

“I feel the same. These are brothers. This is Ishmael and Israel. This is a quarrel between brothers, these are two peoples who have legitimate right to the same piece of land. That has to be reconciled, in a much more imaginative way that either is approaching it today.”

Cohen is the first to admit he doesn’t have any answers. More often, all he has are the soothing or enlightening questions in the shape of prayers or songs. He performed in Israel during an earlier conflict, would he sing there now? “I don’t know whether I could do that now. I’d sing with both parties if that could be arranged.”

How does Cohen react to those who suggest that his power as a poet and singer might be put to more practical use politically, dealing more directly with themes of violence and revolution, whether in Palestine or Northern Ireland?

“I can’t penetrate these tragedies,” he says somewhat hopelessly. “Sometimes I think that if I was running the whole show I could find some common ground between all these conflicting positions because I do understand all these conflicts and the appetites on both sides. But I’m not running the show, so the most I can say is that I understand those appetites and I can’t really make much of a contribution one way or another.”

In the final analysis, Leonard Cohen’s not inconsiderable contributions are made within what he calls ‘the intimate chambers of poetry’, where the personal is the political. And if the war between opposing poles within himself is the starting point for most of that work, then the battle site which occupies much of his everyday life is the external war between the sexes. In this he sees the truest microcosm of society; it is here he takes his stand politically.

Advertisement

“The relationship between the sexes is, finally, what makes us feel either good or bad about ourselves. Sure, it’s not written anywhere that we have to feel good about ourselves but let’s try to get that straightened out. Or at least, at most maybe, try to get a little better than it is. Or has been.”

Whether by strategy or coincidence, Cohen has closed both of his most recent albums with songs which anticipate the final silence. An earlier song, ‘Who By Fire’, was spun around a litany of ways in which we all can meet our deaths. Cohen refuses now to speculate on which form of exit he would choose.

“I do believe it’s unwise to speculate on these matters especially as death looms larger and larger. I wouldn’t dare. Yes, Yeats did choose even the lines for his tombstone but while it’s okay to work it out as he did, within the sacred furnace of his poetry, I’m very wary of casual reactions to such questions. These are serious matters. That’s why I refuse to speculate. That really would be inviting disaster.”

And during those final moments, will Leonard Cohen find any consolation in knowing that, long after he is gone, we will still hear him speaking to us “sweetly / from a window / in the Tower of Song”?

“None whatsoever. It’s cold consolation to know that people may still be listening to my voice and songs long after I’m gone. ‘Cold’ – or no consolation at all!”

He smiles.