- Opinion

- 18 Nov 19

It has been a traumatic couple of weeks for RTÉ, with the death of Ireland’s greatest broadcaster and the botched announcement of huge cuts. So why is the current bout of fire-fighting at RTÉ necessary? In the current issue of Hot Press, published last week, radio producer Ian Wilson – who was at the station for 40 years before announcing his retirement – offered his unique take on what’s gone wrong in Montrose. Here, now, is an extended, and considerably more detailed examination of the crisis afflicting RTÉ.

The death of Ireland’s greatest broadcaster? Obviously, I am talking about Gay Byrne in the sub-headline above. But that line could almost be equally applied to the organisation with which he is forever linked. A period full of symbolism for RTÉ has highlighted a few unpleasant home-truths.

Yeah, sure – across radio, TV, newspapers, online, news, the media has changed, changed utterly. But Gay represented something that is not to be dismissed easily, something bigger than all of the media added together. He represented an idea, and it is this: a broadcaster is a means to have a national chat, that we can all join in with. And for the foreseeable future, the best venue for that chat, by far, is an independent (of government), publicly-owned entity.

Meaning RTÉ.

What kind of independent country would hand that role over to Google, Facebook, Rupert Murdoch, Liberty Global or, for that matter, Denis O’Brien? Not to mention take the risk of losing control of vital aspects of your culture – of our culture – from the Irish language to ongoing support for the full spectrum of the Irish arts, and especially music: traditional, classical, singer-songwriter, rock and on to the newest urban beats.

My cards, therefore, are on the table: Ireland needs strong public media.

Advertisement

BABY WITH BATH WATER

We are where we are. RTÉ is simply the biggest concentration of full-time media/creative/techie types in the country, and for many years some of the finest minds on the island worked in or were associated with the place. They represent a critical mass of exactly what a modern, diverse, open economy needs: a hot bed of ideas and innovation and dissent, with a level of public support. Much of what is produced is superb (subjectively a lot isn’t, of course) and, by and large, the staff take their work very seriously and take real pride in what they do.

Burning the place to the ground and starting from scratch would be an act of monumental stupidity, so it follows, (sadly), that we can’t rule that out.

Given all of the potential it holds, what always had me scratching my head, was this question: why does it seem that the whole is smaller than the sum of the parts in RTÉ? In classic wave theory, this is known as interference, where the ripples coming from different directions (out of phase) can cancel out the original wave and all the energy is dissipated.

The real, and more complicated, alternative is to enable these 1,500 (approximately) to work in a way that amplifies the output, to harness the clearly locked-up potential.

DOWN WITH YOUNG PEOPLE (AND THEIR HORRIBLE MUSIC, CLOTHES, ATTITUDES)

As sure as night follows day, when the news of cuts emerged, various interests queued up to dance on the grave of RTÉ. For many of them, grave Numero Uno to dig is 2fm’s. To me, there are three distinct gangs saying they want 2fm gone. The first two are all-too-predictable: the competitors and the philistines (including those who seem to be down on “the youth” EG: the Greta Thunberg haters), but the third one, those who don’t understand what a vibrant national music station can do for the local music scene, is the group that RTÉ needs to win over.

So, to the direct competitors, some of whom have deep pockets. “He, who cannot be named,” or others like him, would likely dispatch flocks of lawyers in my direction if I were to say too much, but you get the drift. Their views cannot be taken seriously.

Advertisement

The second group are just philistines. They have no concept of creativity, or as the cliché goes, “know the price of everything and the value of nothing.” If the free market can’t provide it, then it’s not worth providing, but they know that you won’t get away with suggesting that the National Gallery is a waste of money, and so 2fm offers them a soft target. For some, this ties-in with a bizarre dislike of young people, or at least their music, clothes, haircuts, political views, sexuality: “Bad enough that we have to put up with this shit, but to subsidise in some way?” Blindboy hits the nail on the head with “The Da’s”. And, yes, really, there are such people.

But in all honesty, most people don’t understand the central importance, and potential, of a public music station in developing and sustaining a stream of new music and talent. This is not just some abstract idea: a vibrant and productive music scene generates work, money, exports, prestige. To do this, and thereby to make it possible for more Irish musicians to (actually) earn a living, requires targeted inputs from official Ireland. We know this. Who can doubt the contribution of the BBC – especially Radios 1 and 2 – to making the UK the second most successful music producer and exporter in the world?

In Irish terms, was it a private radio station that started studio recordings for new bands; launched our first national music showcase; was in at the birth of the Eurosonic Festival; sent new band tours around the country; toured major dance shows across the island; dedicated hundreds of hours of programmes to alternative/new music across all major genres; paid up to €20,000 in fees to Irish artists and producers annually? Actually, you wouldn’t expect a private radio operator to do this. You get the idea?

Do not dismiss the time and effort (and cost) of what Dan Hegarty, Dave Fanning, Mr Spring have done, and are consistently doing, for Irish music, never mind the central role that Adam Fogarty, Tara Stewart (and others) have in the current crop of Irish Urban pop/hip hop artists, and the current and past contributions by Tracy Clifford, Jenny Greene, Cormac Battle , Jenny Huston , Louise McSharry , Mo K , Jim Lockhart, John Power, Conor G, Mark McCabe, Mark Cagney , John Kenny, Penny Rose Harte, Helen(s) Doorly and Cullen, Carol McGrane, Mickey Mac and the late and much-missed Uaneen Fitzsimons and Gerry Ryan.

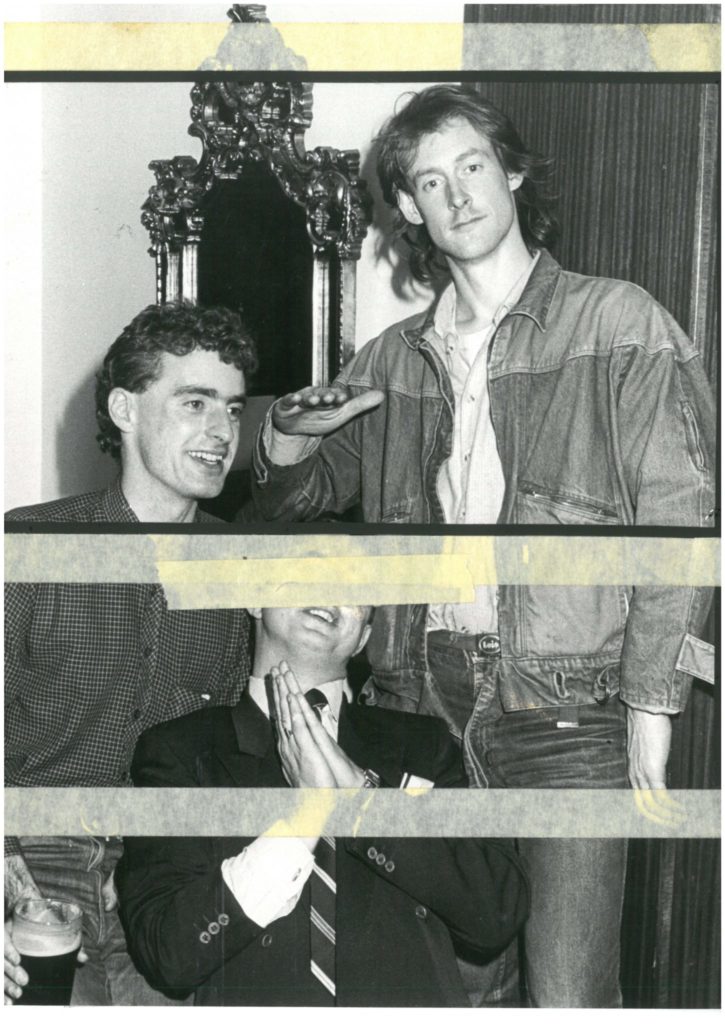

Dave Fanning and Ian Wilson

Dave Fanning and Ian WilsonAt present 2fm is climbing its way back to a central role in the new and live Irish music scene. The Rising Tour, continuing studio sessions, and the commitment to heavy programming of new Irish music are working. It is no coincidence that this goes alongside the upsurge in new music coming out of Ireland. The inclusion of Alan Swan (2fm head of music) on the judging panel for the BBC Sound of 2020 is an interesting indicator. The Beeb won’t invite you unless you know your shit, and your station connects with your local music scene. So, they are doing something right.

Sounds like 2fm has a good case? Well, the problem is… er… that RTÉ seems to be sort of embarrassed to talk about it, very rarely presents this case forcefully and, as a result, the public just don’t get it. So RTÉ needs to work on this third group, and to take real pride in what it does.

Advertisement

LET CONFUSION BE MY EPITAPH*

So, what’s been going on with RTÉ, and why is it in the shit? How come it is losing money? Sure, it is about the cash that social media companies have taken out of the advertising market. It is about the failure to collect the licence fee. And so on. But it is about a lot more than that too.

Does our Government have a clear strategy or policy on what it wants from the likes of RTÉ? Did previous governments? I never saw it and I don’t see it now.

Is there a clear funding system to implement whatever the Government might want (if it knew what that was)? The answer seems to be that RTÉ is a good idea; that it should be all things to all people; and that somebody should pay for it. When you strip away the bullshit and the jargon from the responses of Governments past and present, it’s essentially as vague and unsatisfactory as that.

What is the reality for makers of content in RTÉ when it comes to “Public Service” (License Fee, if you will) obligations? From my experience, at various times, things such as live music, or production of Irish music, or support for new Irish music by diverse programming, or fixed amounts of Irish music, or live festival coverage, or live events (Beat on the Street, etc), or even something as obvious as targeting under 30’s, were deemed to be part of the Public Service brief – and then un-deemed a bit later. I remember compiling lists of how many hours of new/Irish/live music etc. we were putting out every quarter, of regional gigs, of music from all four corners of the island, and on and on, and, maybe two years later being told half-casually, “Actually, we don’t want that any longer, we’ve changed our minds.” And after some passage of time, we re-invented the wheel and the process started again. I can only imagine programme-makers all over RTÉ having similar groundhog days.

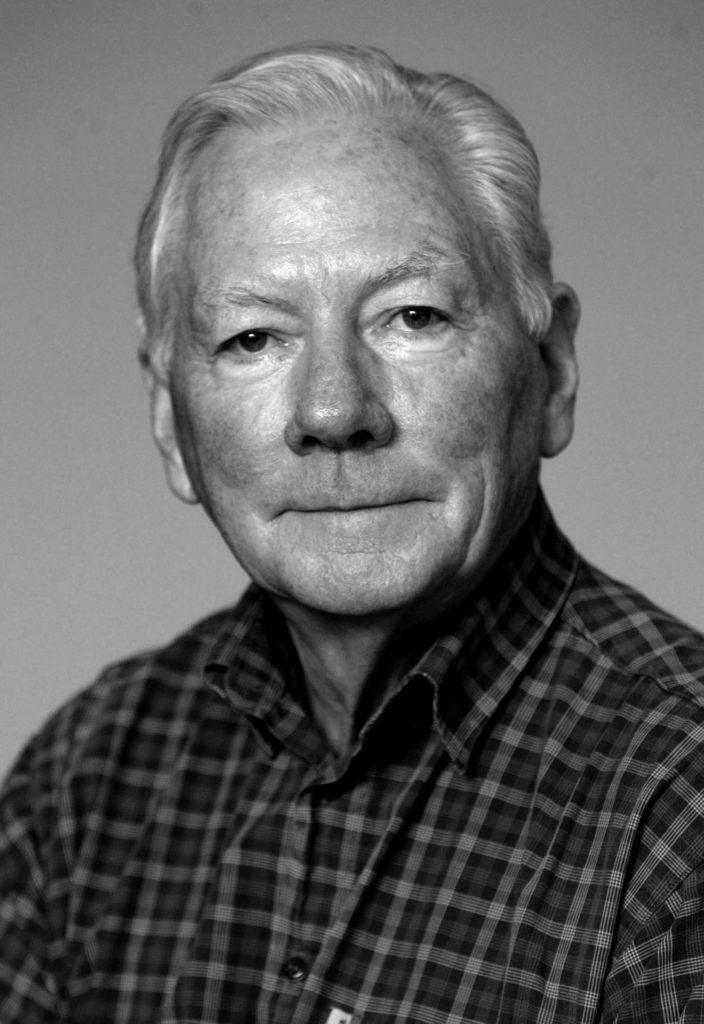

Dirk Sommer(Brian Downey manager), Ian Wilson(RTE 2FM DJ/Producer) and Jim Lockhart(Horslips) at the Tipp Classical 2019 launch at Ryans of Camden Street, Dublin. Photo:Michael Donnelly.

Dirk Sommer(Brian Downey manager), Ian Wilson(RTE 2FM DJ/Producer) and Jim Lockhart(Horslips) at the Tipp Classical 2019 launch at Ryans of Camden Street, Dublin. Photo:Michael Donnelly. Advertisement

This is not RTÉ’s fault. The constant changing/blurring of goalposts by various Ministers, Departments, Dáil Committees, Authorities and Boards is confusing, to say the least. A good illustration of this was one Limerick TD melting the handle of the Parish Pump on the closure of the current RTÉ studio in the city. Meanwhile, in the real world, the fact is that RTÉ has two large and less than fully utilised studios in Limerick and Cork, with all the costs associated with bricks and mortar premises. It is a no-brainer to close the smaller one and combine the production facilities, leaving a compact regional news operation in Limerick.

Some years ago, RTÉ sent in a delegation to the Dáil Communications, Media, Culture (or whatever combination of those it was at that stage) Committee, where we were set upon by various politicians for not playing enough Big Tom, ballad groups, middle of the road singers, not having enough orchestras or string quartets in various cities – some of the stuff was well “left-field”!

In fairness, a number of those present were supportive of what RTÉ Radio did for Irish Music. That, by the way, was the reason for our appearance. I kept my head down, but after an hour or so, the total incoherence of the proceedings got to me. I suggested to the politicians that, if they were serious about promoting and developing Irish music, there’s a whole range of models and ideas in use across Europe for public support of local music. These include music export bodies, Arts Councils and music business funding, co-funding etc, and that an artist’s success is only partly dependent on Irish radio play, important though that is. Finally, I said that I had for years worked on promoting and helping new Irish artists, and that working across the EBU/Eurosonic area had given me some insight, and that we (RTÉ) would love to come back to talk further about the ways forward to assist in promoting Irish music. RTÉ never heard back from the Committee.

MEDIA CAR-CRASH

Well, Government fucked-up completely and RTÉ is in a mess. But then, this is just another part of an awesome lack of official awareness of how a population of less than 5 million people establishes – or indeed might maintain – an identity in the modern media world.

If the major responsibility for this slow-motion media car-crash can be laid at the feet of Government, it was still RTÉ in the driver’s seat.

I spent many years making myself less than popular in RTÉ by constantly pointing out how inept much of the station’s online presence was. Indeed, at one staff meeting, maybe seven or eight years ago, I confronted the Director General of the time, lacerating the Radioplayer and many of our online production tools. I also pointed out that our extensive live festival coverage, amounting to dozens of videos, sessions and live music pieces (posted from a field) happened despite our digital/tech divisions, rather than because of them. Maybe it’s the way I tell ‘em, but it went down like a bucket of cold sick and they all ganged up to poo-pooh and dismiss what I was saying.

This is, of course, an example of HUBS (Head Up Bottom Syndrome). But, more tellingly, that point about the weakness of RTÉ’s online presence was all over the coverage of the station’s current financial crisis.

Advertisement

Were there really no grown-ups listening to what many programme-makers were saying for over a decade? It appears not. In 1997, when I started live-streaming video from live dance events, nobody ever came to me and said, ‘You’re on to something here’. That’s all of 22 years ago, to save you having to do the sums.

LACK OF BOTTLE

That lack of clarity about how – or even why it would be a good idea – to gear the station’s output to the internet, explains why RTÉ did not move to the concept of unitary content production when it should have, in the mid 2000’s. Radio, TV, and all the rest of what happens, should have been merged into a number of different production areas, each with the brief to make stuff and get it out there, by every means possible: FM, digital, TV, satellite, streaming, podcasts, on demand, shagging carrier pigeon, if it works. That’s not to imply that there was much support for this view across the organisation, at that time. There wasn’t.

And maybe it was down to lack of bottle, that same lack of bottle which the public identify in every focus group and survey I have ever seen. “Risk averse”, they say. “Won’t take chances”. “Safe”. That’s the tenor of the widespread perception of RTÉ.

Which brings us back to Gay Byrne. There were many reasons why he was so successful, but one that came up all the time in the tributes that were paid to him over the past week or so was his willingness to take chances, be a pioneer, tackle taboos – and everybody knew he had to have some bottle to push this through the safety-first, arse-covering culture that abounded in RTÉ and still does to an alarming degree.

And did the public love him for it? Did they love Gerry Ryan for the same reason? Young Offenders, The Rubberbandits? You get the idea.

At this stage, it is worth pointing out that many RTÉ managers, at all levels, did, a lot of the time, stick their necks out to protect their staff. I know this personally and many of us appreciated that support from our programme heads. There was, also, a certain amount of judicious “turning a blind eye” and various understandings with your managers, that enabled “stuff” to happen. So, to characterise the whole place as craven and spineless is a serious mistake, but there is no doubt that the prevailing vibe was not to take chances (if you valued your career).

The chances that we took on The Dave Fanning Show back in the day would get us fired today: live midnight interviews, with swearing, drinking, occasional jazz woodbines, the odd physical confrontation, streams of consciousness, naked people, etc., involving some of the biggest names in music at the time. But we had the bottle to carry it through and it was a part of what made Dave a legend (and why I survived to retirement).

Advertisement

Sorry, I have no magic solutions to RTÉ’s current difficulties. Perhaps there aren’t any. But if you are really interested in the issue, there is a very useful “Peer-to-Peer” report on RTÉ, done by the European Broadcasting Union in 2018, and it hits the nail on the head in so many ways.

And is it available on the RTÉ Website? Not that I could find, but I stand to be corrected.

*Lyrics courtesy King Crimson!