- Music

- 27 Jul 23

One of Sinéad O'Connor's most remarkable interviews with Hot Press took place in December 1992 – just a few months after she sparked a major controversy by ripping up an image of the Pope on the US TV series Saturday Night Live, and calling on viewers to "fight the real enemy." Here's that iconic 1992 interview in full...

Originally published in Hot Press in December 1992, under the headline: DON'T CRY FOR ME

When Sinéad O'Connor tore up a picture of the Pope on the Saturday Night Live television show in the US recently, she unleashed a storm which has been swirling around her ever since, causing her at one point to announce her premature retirement from the music industry. One month on, bruised and weary she may be – but Sinéad is neither downhearted nor repentant. Having declared war on the Roman Catholic church, she is determined to keep taking the battle to the real enemy.

Interview: Niall Stokes

It’s eight thirty on Saturday evening and the phone rings. The voice on the other end of the line is familiar to millions of people throughout the world.

“I don’t know if I expressed myself clearly when we were talking,” Sinéad O'Connor says. “I was just thinking that it’s really all so simple…”

Advertisement

There’s a pause on the line like a deep inhalation and I can imagine the fiery intensity in her eyes.

”Do you know what I mean?” she continues reflexively. “I don’t believe that we believe in God. Proof of that is the existence of child abuse. It would be perfectly fucking simple to end all the terrible things that are going on in Ireland and the world. The fact that they’re going on is proof that we don’t believe in God. We could so easily stop all this.”

She breaks and then accelerates into another train of thought, explaining the emotional turmoil that she’s experiencing. There’s been another atrocity in Belfast, another four (or is it five?) broken corpses on their way to the morgue. Dust unto dust. And in London, IRA bomb-making equipment has been found. Arrests have been made and a troop of volunteers face a stretch of years behind bars.

“I’m on the side of human beings,” Sinéad says. “I’m on the side of babies. As long as we’re fighting each other we’re not fighting the real enemy. Why aren’t Irish people doing more to stop it? There is an answer to the problem. If we loved each other we could work it out.”

She talks about love, forgiveness, knowledge of yourself. She talks about unconditional love.

“We’ve all been taught that this is how it’s meant to be,” she says. “People think that this is normal? You don’t just turn over and go to sleep. You don’t just go to sleep…”

There’s another pause, like an even deeper inhalation. I am aware of the closeness and the distance. Dublin, London, Los Angeles, the World. So near and yet so far, all wrapped up in this voice of simmering intent. “People have gotta wake up,” Sinéad says and she exhales audibly.

Advertisement

On Saturday night, I don’t go to sleep. “We’ve all been taught that this is how it’s meant to be.” I hear her voice. “People think this is normal.” I hear her voice. “People have gotta wake up.” I hear her voice.

And in my heart a terrible fear uncoils. In the distance the forlorn sounds of night ebbing away. A police siren announcing that someone somewhere is – as someone always is – in trouble. The hum of passing engines trailing towards still suburban gardens. And an unidentifiable low static which tells me that the streets are quiet, truly quiet. And I am here, lost in my own shroud of darkness, incapable of transcending images of the violence that lurks behind those mute doors and walls. A woman beaten, a child scarred, a man staggering on the stairs and Ireland sleeps.

A terrible fear uncoils.

**********

War, Sinéad O’Connor sang on Saturday Night Live and then she declared it, tearing up a picture of the Pope in front of a disbelieving cameraman, who zoomed in close, uncertain of what he was seeing, to pick up the image of the shredded pontiff in unmistakable detail. She was fighting the real enemy.

“I wanted to stir shit. That’s exactly what I wanted,” she says now. And so she did.

Advertisement

“I definitely feel that the last few weeks have aged me,” she reflects, stubbing out another cigarette with an unconcealed vehemence. “See I set myself up to be abused basically. I spent, from the picture was torn up until last Wednesday, being beaten up by people left, right and centre. Everyone. All the time. So it was a bit mental.”

She smiles wearily.

What kind of thoughts were going through her head as she was tearing up the picture?

“All kinds of thoughts. More personal thoughts than public thoughts, because it was actually a very personal kind of thing as well. The photograph was a picture of the Pope in Ireland. It was a picture which belonged to my mother, and which was one of a group of photographs that I had belonging to her – so there was a whole subconscious personal thing going on there. That’s what I was actually thinking about."

She knew that the action was a provocative one, that she was taking the battle to the real enemy – and that there would inevitably be a hostile reaction.

“But I wasn’t aware of just how hostile it would be – as I discovered at Madison Square Garden,” she says. “I wasn’t aware of how unchristian people can be in the name of Christianity. I would never have gone and hired a steam-roller and steam-rollered copies of my album. I knew that there’d be a big deal and that’s why I did it, but I was still horrified by that.”

And by what happened at the Bob Dylan tribute gig in Madison Square Garden, where half the audience turned on Sinéad with a terrible ferocity…

Advertisement

“The energy in the room,” she says and stops – contemplating the memory, hunting it down so that she can understand and exorcise it. “You know when you’re on stage, you can pick up the energy of the room – it goes into your body and through you and back out…”

She stops again.

“... well I’ve never experienced anything like this before. I’ve never heard a sound like it in my entire life. Half of the crowd were cheering and half were booing and there was this violent clash, this violent noise. It was the weirdest noise I’ve ever heard.

“And what it did, this terrible noise – it went directly to my stomach. It made me want to puke – so all the time, I was just trying not to puke. So when they said I was crying – I was not fuckin’ crying. In fact, I was puking. And for two weeks afterwards I still felt like throwing up. Certainly for the first four days I felt very sick. That night is what aged me – the venom, the hatred. I had experienced that before in a different situation. That’s why I was so frightened.

“All the time I kept thinking: I’m not going to let this fear make me say that what I’m saying isn’t true. I’m not going to let it. It was that fear that was making me sick but I wasn’t going to let it get to me…”

And so in the act of defiance she sang 'War' again, fighting back the retching sensation, holding down the bile while her voice rang out in protest across the vast Madison Square Garden arena. Backstage afterwards, Bob Dylan didn’t offer the support he might have been expected to. He wasn’t the only one.

“A lot of people were very detached,” she says, “for the most part those who spoke to me were very supportive, particularly the women. Nanci Griffith, Sophie B. Hawkins and Roseanne Cash, they were all really nice. And Kris Kristofferson was like an angel sent from heaven.”

Advertisement

In the aftermath of the incident, Sinéad arranged a press conference in London, which was eventually cancelled at the last minute…

“They set up this rehearsal press conference here at Chrysalis," Sinéad explains. “They weren’t trying to get me to cancel it, they were just trying to make sure that I understood that I was going into a fuckin’ dogfight here, and that these people did not want to listen to what I had to say, and that they were out to brutalise me and make me out to be a mad woman. It was Roy Eldridge, the head of the company, that was concerned enough to do this – so they all sat there and played the role of the journalists and went through the whole thing. And eventually it did become apparent that, if I had gone and done the conference, there would have been an animal fight.”

It was against that kind of intensely emotional and stressful background that Sinéad declared she was retiring from the music business. It was a misleading impression that she’s determined now to correct.

“I said it,” she freely admits, lighting another Camel, “that I was quitting. But it’s not true. There was madness going on in here and I was feeling like I was dying. Everyone was screaming and there was a very tense scene going on and I was doing an interview in the middle of this. Just beforehand I’d had that conversation with someone from the record company: I had said that I wanted to put out ‘Don’t Cry For Me Argentina’ as a single but I didn’t want to do a video and he said, ‘Well if you don’t do a video, it won’t be a hit’ and I said I don’t care if it’s a hit and he said, ‘What’s the point of putting it out if it’s not going to be a hit'.

“That was just before I did this interview and I was just thinking, ‘Fuck this for a game of fucking darts’. But afterwards I realised that I couldn’t get away from it even if I wanted to. But I wouldn’t want to, anyway. I’d just like things to be different. What I was saying in reality was that I want people to stop abusing me, please. I wanted to run away from that.”

She says it again.

Advertisement

“I wanted to run away.”

**********

There’s a lull while some more cigarettes are sent for. The butts are beginning to mount in the ashes to ashes tray and Sinéad stares into the middle distance surveying the wreckage not just of the past few weeks but of the bruisingly contradictory industry of which she is unwillingly but desperately, necessarily, a part.

She blows a long hard jet of smoke that traces a clear line for an instant at an angle across the room and then dissipates into a cloudy haze that hangs ominously in the air. I can’t help thinking of all the cancers that are stealthily gnawing away at people’s hearts and bones and blood and guts and souls.

“I was just so fucked that I couldn’t deal with actually going and having to physically make a video,” Sinéad says emphatically. “And also it all seems so fuckin’ pointless. It all seems so completely pointless at times. Not all the time. Singing doesn’t – but all that other shit you end up doing. When I put the record out and I ended up doing all these TV shows and you go out and mime your fuckin’ record and everybody knows you’re miming.

“It’s pathetic and it’s soul-destroying, the things you have to do, all the rounds that everybody does, the whole circus. I don’t get off on it. You know, in one way I’ve reached the peak of what we’re supposedly aiming for and it bores me. I like singing but the rest is just fuckin’ bullshit. It’s just soul-destroying.”

Advertisement

She contemplates the notion of despair, of looking into the black pit and feeling that we are being overwhelmed.

“Doing these rounds makes me feel suicidal,” she states bluntly and looks at me. “I do despair, I totally despair but then I know that everything changes and that it is changing.”

She takes another pull on the cigarette she’s been tapping absent-mindedly into the ashtray…

“But, yeah, I fuckin’ really do despair. But now I know that I just won’t do it anymore. I’m not going to go on tour. I’m not going to do all that shit. I’m not going to do all those stupid TV shows. I’m going to do what I want to do, which is sing, make records, put them out and do a couple of shows. There’s just no point in all the other bullshit.”

It isn’t the only aspect of the music industry that fills her with revulsion.

“I think it’s dying,” she reflects and then twists the knife. “I hope it’s dying. I think its age is over. Poets, composers, sculptors, movie stars – they all had their age, and then there was rock stars. And now I think it’s dying. I don’t think the music will die but the industry can only die because it’s based on something fundamentally corrupt.

“The pursuit of material success, the worship of money, is fundamentally corrupt. And in the service of that corruption, the music has been controlled. What we’ve been allowed to do as artists has been controlled and we’ve been controlled. They’ve made us feel like they’re doing us some favour, like we’re privileged if we get paid 18½% of what we actually earn through our suffering. That’s some fuckin’ privilege.

Advertisement

“I think that the only thing that can be done to wise people up is for artists to come together, to establish some kind of co-operation between artists, so that we can talk to each other and become friends and understand each other’s experiences.

“We need to take back the power that we have given away and take the Pepsi emblem out of the corner of the video and put something else there instead, and don’t do the interview from the back of the limousine, and get rid of the diamonds, the jewellery, the crap, and the bullshit.”

She isn’t pausing for breath now, instead pushing the argument relentlessly forward to its conclusion.

“When you’re an artist and you walk down the street, if you walk down the street, you give the message by the way you look, by what you wear, by every single thing – people clock it, and they get the message. So we have to take back that responsibility. We have to realise that for the most part we’re giving material messages to people. We’re telling people in effect that if they pursue money they’ll be happy.

“We’re going along with this. We’re altering our looks so that we can sell more records. We’re altering our music, drastically, so that we can sell more records. We’re selling ourselves. We’re giving ourselves up to serve this bullshit industry. We’re not being artists in the true sense of the word.

“We need to start being artists again. We have to have the courage to be artists. It’s by inspiration that people learn.”

And it’s by inspiration that artists live. Sinéad was quoted somewhere recently as saying that she wasn’t interested in writing songs anymore, that she was only interested in singing. But the hand-me-down nature of the material on Am I Not Your Girl notwithstanding, she hasn’t abandoned that vital aspect of her creativity.

Advertisement

Her face lights up at the thought and she smiles a full, self-confident smile for the first time since we started talking. “There’s been a lot of inspiration these last few weeks,” she says and then she retreats, back into herself, shy again but still smiling.

She won’t be drawn on what kind of songs she’s been writing. “You’ll just have to wait and see,” she counters, nodding her head rhythmically as if in time to the beat of some inner soundtrack, a new 'Troy' or 'Mandinka' for 1993…

“I don’t know when I’m going to record again,” she adds, “but I’m in no rush. I mean I kinda am because I obviously want to continue the struggle – but you can do that in all kinds of ways.”

The inner drum is beating more quickly now. “You can’t just fuckin’ go to the studio. Not if you’re making records for the reason that records should be made, which is the expression of human feeling of one kind or another. You can’t just churn them out every year or every couple of years. You’ve got to experience things, you’ve got to study yourself very well.

“I never understand when people go into studios and write in the studio. They go in to make an album. It’s not that they were really fucked up one night and wrote this fuckin’ song – which is how I write. I only write if I’m really fucked up. It was always therapy for me.

“Most of us, certainly the one I know, have been through horrific upbringings. If we realise these things about ourselves and get to know ourselves and make some effort to heal ourselves and if we do it publicly, then we can bring the truth to people. And if we bring the truth to people we can help them.

Advertisement

“We are all abused children,” Sinéad O’Connor says and when she say it, it is impossible not to share the sense of outrage that she feels about the accumulated injustices that are heaped upon us whether by church, state, schools, teachers, priests – or parents who have themselves never understood the meaning of the word love.

Some of us are lucky. Some of us are not. And then you think of the six innocent children preyed on, indecently assaulted and buggered by a Christian Brother into whose hands they had been entrusted as part of their education – and in your heart there is the sound of crashing thunder, and fork lightning flashes through your bones, and you know that there are some things which will never be redressed.

And a terrible fear uncoils again and this time it feels like it won’t let go.

**********

Most people struggle to find an answer, to understand why these atrocities happen. What is it in the human spirit that enables George Bush or John Major to do business with Saddam Hussein, to sell him arms and ammunitions one month – and to order the mass annihilation of defenceless Iraqi troops in retreat from Kuwait the next? What evil is at work that a Christian Brother could impose his twisted sexuality sixty-eight times (and Jesus knows how many more) on six defenceless boys?

Most people struggle to find an answer and then, overpowered by the sheer horror of it all, retreat into despairing disbelief. Others don’t even bother to get to the stage of caring at all and sleepwalk through life, oblivious. Sinéad O’Connor not only refuses to sleepwalk, she believes that she has identified the culprit.

“The only reason that I ever opened my mouth was so that I could do this,” she says, her voice compressed with urgency. “All of my songs are about child abuse. I am a child that’s been abused. That’s who I am. That’s what I am. So anytime I do anything, that’s what it's about. My role has always been by any means necessary to fight child abuse. That’s the only reason that I ever sang and it’s what kept me alive. But to fight child abuse, we have to fight the cause rather than the symptoms.”

Advertisement

I point to the ashes and butts piled high on the ashtray since we started talking and Sinéad smiles wryly.

“It’s a vicious circle,” she says and exhales. “One always becomes self-destructive when one is being abused. You end up having self-destructive tendencies. Kill yourself with cigarettes or kill yourself with a gun.”

She shrugs. “I remember making a conscious decision to kill myself by cigarettes when my mother died. I decided I was going to smoke myself to death. I think subconsciously that’s what people do.”

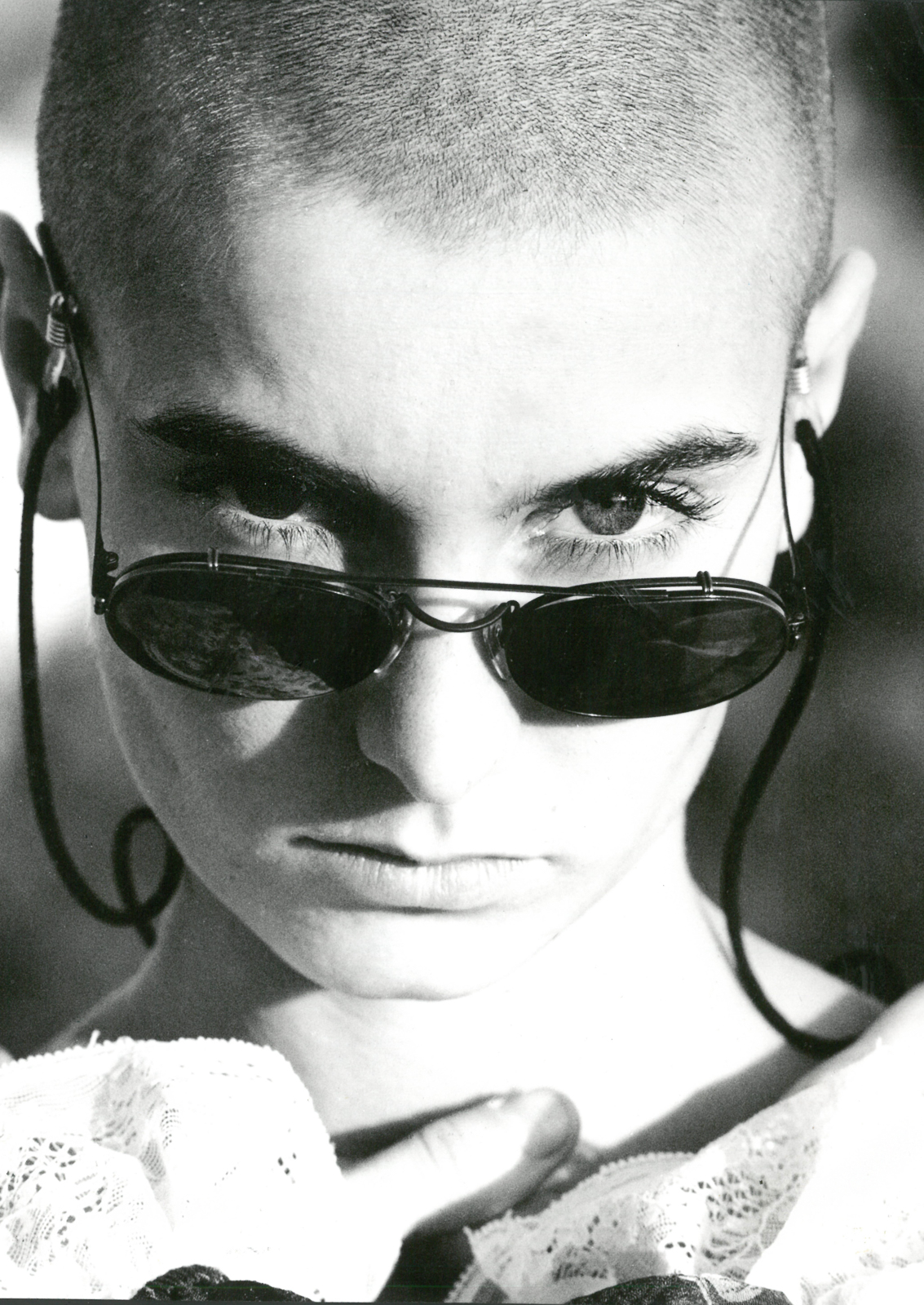

Sinéad O'Connor. Copyright Leo Regan.

And what fuels this appetite for destruction? What feeds the perverse desire to brutalise one another, and especially to abuse children who cannot be foisted with the burden of responsibility?

“It’s the highest manifestation of evil,” Sinéad suggests, “the act of raping a baby or a child. But the people who do it are merely following the example set for them by the church, who taught us to do it in the first place by giving permission for the destruction of entire races for money in the name of Jesus Christ.

Advertisement

“A christian is supposedly someone who asks themselves in any given situation, what Jesus Christ would have done – and does it. I don’t believe Jesus Christ would have authorised the destruction of entire races in which the church participated. I don't believe Jesus Christ would have authorised the burning of witches. And I don’t believe that he would have authorised the persecution of women who want to have abortions.

“It’s my belief that the church wants to ban abortions simply as a way of preserving their power over people. Their power comes from people growing up in fear. They know that if abortion is effectively stopped, millions of children are going to be born into circumstances under which they will be resented and abused and this is what they want. They want to control people through fear and abuse.

“But what they’re doing is anti-Christian because the very thing that God gave us that makes us human beings is choice – free will, the right to choose our own destiny. The issue isn’t pro-life or pro-abortion. Nobody wants to have an abortion but the thing is about choice, it’s about having the right to choose your own destiny.”

They want to control people through fear, through keeping them in a state of intimidation and awe.

“It’s very interesting. The more brutalised people are, the more acceptable Catholicism seems to become. The people are starving in Africa, they’re dying, and the church is planning to build a Basilica there. It’ll cost hundreds of millions of dollars and yet they’ll do that instead of feeding people, because what they want is power.

“In the Dominican Republic they’ve built this huge lighthouse dedicated to Columbus, for seventy million dollars. The average income in that country is seven hundred dollars a year. There is extreme poverty – and they shifted thousands of people off the land to build this thing which beams huge crucifixion-shaped lights out into the sky in celebration of what Columbus did.”

In celebration of what Columbus did, indeed: the slaughter started here. Seventy million dollars is a very conservative estimate of what this monstrous conceit cost but no matter: the obscenity of it is irrefutable.

Advertisement

“Where does the money come from?” Sinéad asks. “Why have they made themselves into a State? Why are we not allowed into the Vatican to see what’s in the vaults, to see the stuff that they have taken from entire races of people that they slaughtered on the battle-fields of France and of the East? Why can’t we see the religious regalia that they stole from the Coptic Christians in Ethiopia, which is why Mussolini’s forces went in there in the first place – the Pope blessed Mussolini’s forces before he went into Ethiopia to wipe out the oldest Christian community in the world.

“The Vatican remained silent throughout Adolf Hitler’s purges because they were responsible for them. They invented anti-Semitism.”

There’s no let up in the intensity of Sinéad’s convictions about the church’s hypocritical abuse of its power. And of course she’s right. Her words pour forth, in biblical torrents.

“I think we should be allowed to do an audit on their accounts. I’d like to see their accounts for the last few hundred years but especially for the last fifty or so. In the first palace, if we could insist on seeing their accounts in Ireland it would be an example to the rest of the world. Ireland is the microcosm, but every country in the world is affected by this. In the first place we should look at their accounts. Establish what property they have and how they got it. Exactly how they got it, and exactly what their money is being spent on and how much tax they pay.

“We should be allowed to get into the Vatican to see every single piece of paper, every single document, every single item they took from people.”

Expounding ideas like these, and tearing up a picture of the Pope on prime-time television – does Sinéad ever worry about the extent to which she’s exposing herself, and the possible consequences?

“If I’m going to offer myself for service I have to take these things into account,” she says. “If you declare war on an enemy, that’s a risk you have to take – and you just have to have faith in the fact that you’ll be looked after. Whatever is gonna happen is gonna happen.”

Advertisement

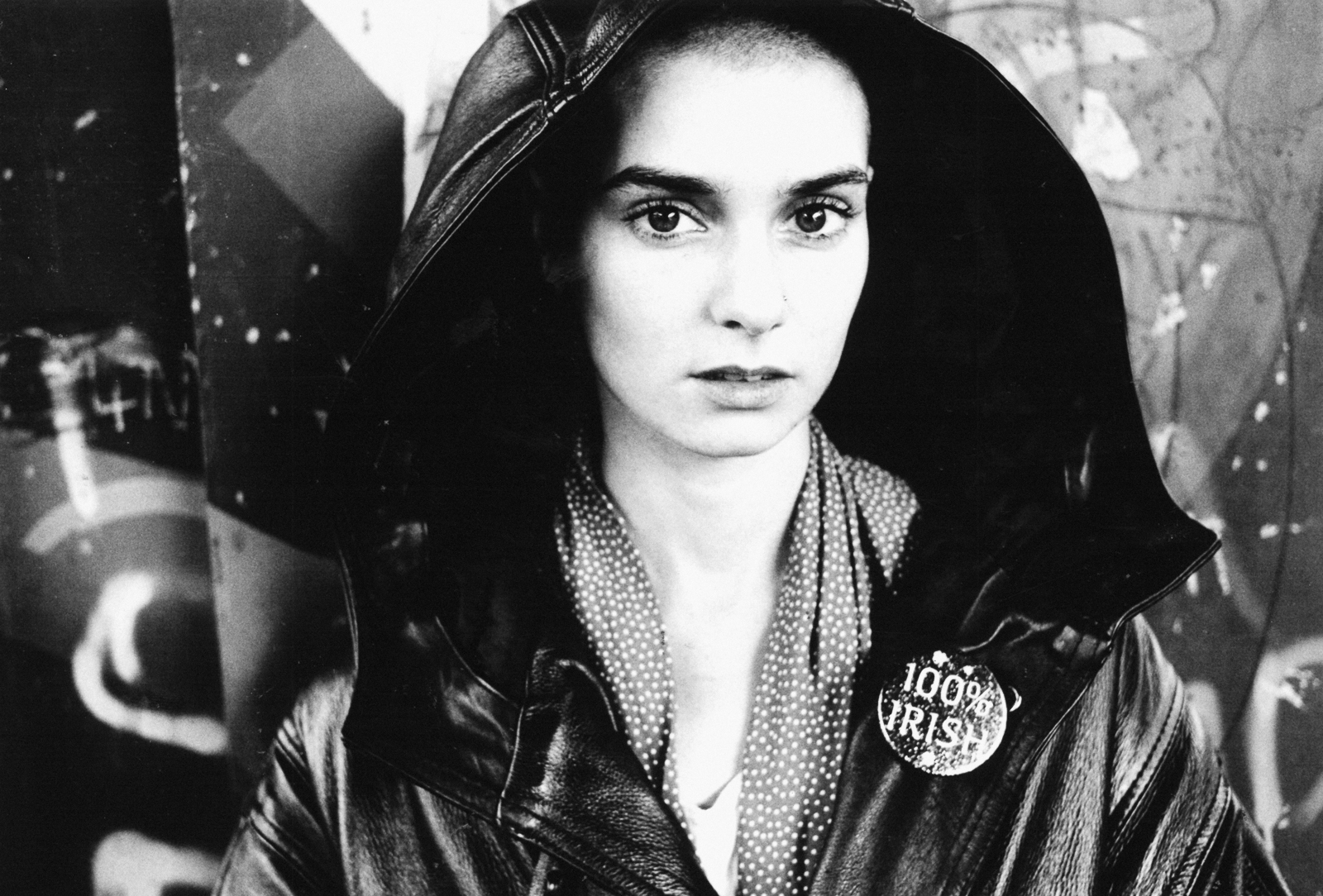

Sinéad O'Connor in Los Angeles, 1991. Copyright John Russell.

**********

By now the ashtray is overflowing and the small room we’re in is leaden with smoke. You’d think Sinéad would be tired and maybe she is, but her intensity never drops. She talks about her own horrific experiences of child abuse but she’s anxious to not do or say anything now that would make life any more difficult for her family. It is imperative, however, that people who have been abused should speak up. This she believes.

“A conspiracy of silence, that’s what keeps it going. That’s why it’s so important to scream and shout. Even the places where the social workers are sending the children are often not helping them. I know because I lived in one of them. They’re punishing them, instead of talking to the children and helping them.

“The RSPCC were called by our neighbours to come out to our house and they wouldn’t because they said that people who lived in Glenageary didn’t beat their kids up. The people were in and out of our house and nobody did anything. Teachers didn’t do anything.”

Does she ever feel bitter towards Ireland about that conspiracy of silence?

Advertisement

“The only times that I’ve felt like killing myself have been in Ireland, when I’ve been abused,” she says matter of factly, “in particular during the IRMA Awards the last time I was there. It’s the Irish that do that to me. I always think of Ireland as an abusive mother, who punishes her children for acting out what she would rather keep secret. I make them see things inside themselves that they don’t want to see. I’m living proof.”

Her wide eyes narrow in hurt and in anger. “There were phone lines in the Irish papers – if you think Sinéad is barmy phone this number. Bastards! I don’t care what that does to me, or what kind of traumas it triggers off in my system. They don’t even think I’m bonkers. They just know that they can make a lot of money out of it. Animals! I’d like to know if I get a percentage of the money. I’d like 20% and I'm going to be invoicing.”

How does she feel about how Madonna has been portrayed in the media?

“I feel very sorry for her because she must be feeling very brutalised herself, having to suffer being analysed by people whose schedules are up their arses. I don’t think it's really patronising for people to try to be Madonna’s shrink. It doesn’t really matter what she's doing – if you like it, you like it.

“It’s not fair to abuse her and call her a whore and make out she’s some kind of slag. It’s really horrible, really hateful. They know that sex sells papers. And they’re all at home anyway, masturbating looking at it.

“But my main response is that I feel really sorry for her ‘cause I know from my own point of view how upsetting it is and she gets it on a far larger scale than I do.”

**********

Advertisement

Sinéad talks about love, forgiveness, knowledge of yourself. She talks about unconditional love and what she feels about Jesus Christ. She smiles when I mention Tori Amos’ confessions of a sexual interest in Christ, and her suggestion that he represents the ideal man for a lot of women.

“Basically the ideal man would have to believe in God,” she says, “and to put into practice what he believed in. He’d have to be extremely good looking and extremely sexy. And he’d have to be able to cook – ideally, a priest or somebody like that. So I suppose the Jesus thing has a lot to do with it!”

Talking ideals, she’s convinced that we could do away with money – and that the world would be a better place if we did. And she also believes that everybody should smoke marijuana. This, certainly, is a vision of Utopia…

“Yeah absolutely, I think they should pump it into the earth’s atmosphere daily,” she smiles. “Spliff is simply not a hallucinogenic. When you smoke it your feelings and your thoughts become more clear to you., when you’re really stoned all your feelings are apparent to you and you can't ignore them and because of that you end up having to deal with them. It’s an eye opener.”

It’s been a long conversation and the ashtray is piled high now, to overflowing. A bit of levity is in order, that’s for sure.

“Marijuana grows very well in Ireland,” Sinéad says. “If it was legalised it could make a lot of money for the country — although we’re going to get rid of money eventually, aren’t we?”

And she smiles in a way that says: ‘What the fuck’? You have to be able to smile.

Advertisement

Or else you’d fuckin’ cry.

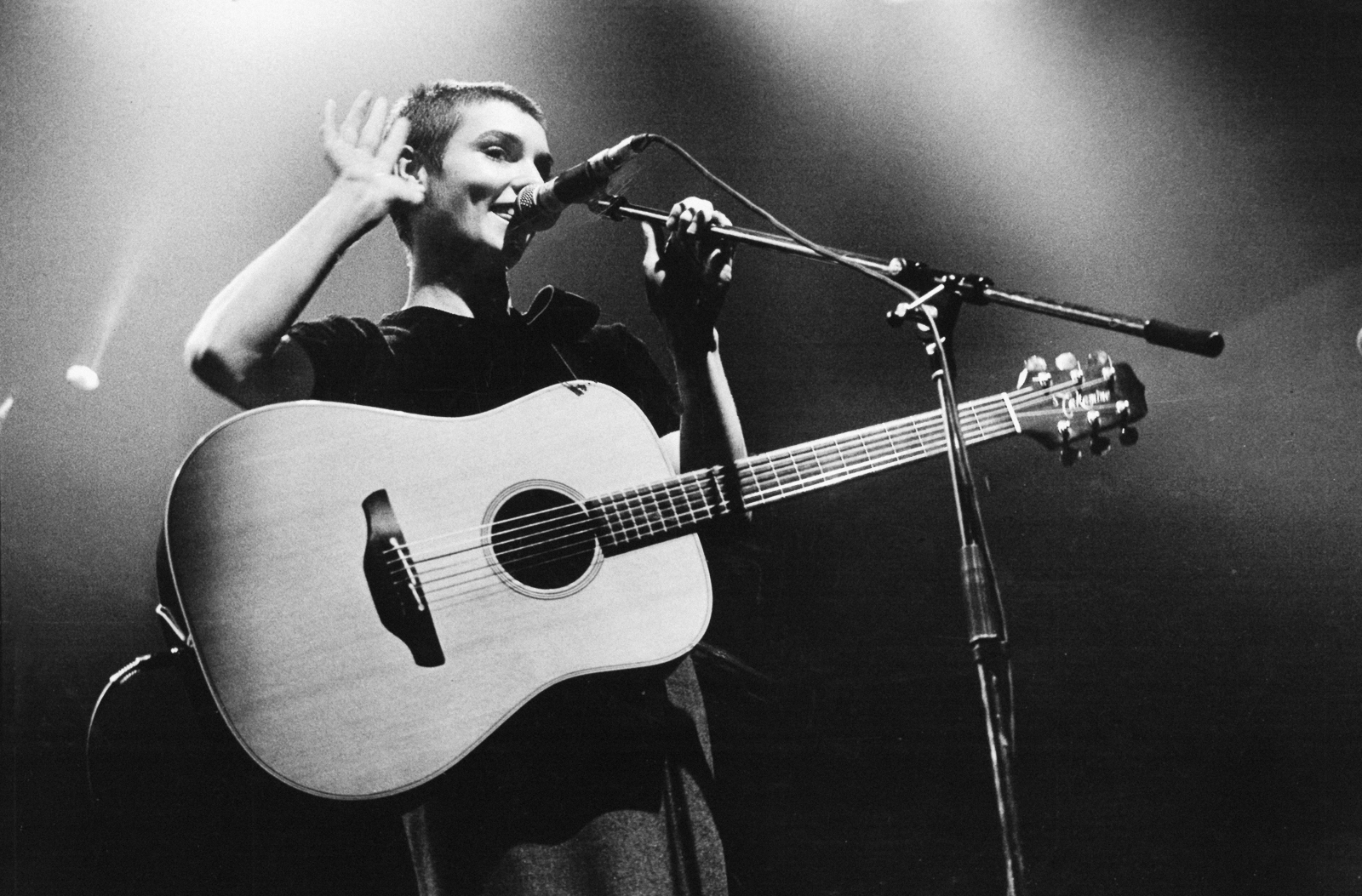

Sinéad O'Connor. Copyright Cathal Dawson.