- Opinion

- 09 May 22

It has been a long time in the making. Dozens of people have contributed exclusive material, photographs, memorabilia and more. It has been welcomed with open arms in the historic – and sometimes controversial – city of Tulsa. And the first unveiling was attended by Dylan scholars, journalists – and at least three of the towering artists of the past 50 years in Patti Smith, Elvis Costello and Mavis Staples…

There is a place in downtown Tulsa, Oklahoma, that they call the Center of the Universe. It is in the middle of the Boston Street Bridge that connects downtown to the Greenwood district, and if you stand exactly in the center of a small circle of bricks patterned into the cement, you can’t hear anything but any sound you yourself are making. The loudest echo I’ve ever heard of my own voice was generated by the inexplicable phenomenon that defines “the Center.” This past weekend, Tulsa received a new Center, one dedicated to the arts and life of Bob Dylan. From May 5-8, as the VIP opening ceremonies and events unfurled, a newly remade building on Reconciliation Way became the center of, not the universe, but the multiverse, for those who admire Bob Dylan and his works.

I was so fortunate as to be there with good old friends, musicians I have loved and respected all my life, and a whole host of kindred spirits – from local residents thrilled with the new arts center in town to journalists, artists, distillers, music production specialists, and architects who had traveled from all over North America, from London and Sydney and Berlin.

Dylan’s own archive, purchased by the George Kaiser Family Foundation directly from Dylan in a sale organized by New York rare books dealer Glenn Horowitz, and brought to Tulsa after 2016, forms the heart and soul and most of the holdings at the Bob Dylan Center. In this article, I’ll be going deep into what we know the archive holds, and how the Dylan Center makes it accessible to both the public, in an exhibition that goes on view after May 10 and that will render you wordless and breathless, and for serious scholars of Dylan. It is vitally important, though, to acknowledge the contributions of individual people and their generosity in composing a world-class archive like that held in the Dylan Center.

Mitch Blank

Advertisement

The gentleman standing on the Center of the Universe in this photograph is Mitch Blank of New York City. Bob Dylan once sang of a “hypnotist collector,” and I can never hear that line without thinking of Mitch. Without him, and his astounding archive of Dylan recordings and memorabilia, the Bob Dylan Center — for which he is now an official archivist — would be a much poorer place. Mitch is wearing his original Rolling Thunder Revue jacket in this picture. Walking with him through Tulsa on this sunny summery day was Bill Pagel of Minnesota. Pagel owns tens of thousands of photographs of Dylan and related to Dylan, concert posters, manuscripts, and both Dylan’s childhood home in Duluth and the house in which he grew up in Hibbing. The website Boblinks.com, which Pagel created and has run for decades, is invaluable to anyone who writes about Dylan or follows his career.

Pagel and I stood in front of one of his many donations to the Dylan Center, a digitized version of an 8mm film he shot in 1980, and he told me about taking it. The clip shows a section of a performance of ‘The Groom’s Still Waiting At the Altar’ from Dylan’s Gospel Tour days, at the Warfield Theater in San Francisco on November 15, 1980. It would prove to be the last time Mike Bloomfield performed live. The electrifying guitarist, who lights up Highway 61 Revisited and whose licks on ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ are forever enshrined on rock and roll’s Olympian heights, helped Dylan go electric at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, but declined to tour with Dylan at that point. Dylan has rightly called Bloomfield “the best guitar player I'd ever heard.” He joined Dylan for a searing, soaring ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ early in the set that night, and returned for the new gospel track. Slight and black-haired, in a black leather jacket, Bloomfield graces the stage all too briefly, but spectacularly, in Pagel’s film. Dylan calls out his name, and throws both arms around his friend as the applause rains down. Three months to the day later, Bloomfield was found dead behind the wheel of his car. He was just 37 years old.

Dylan wasn’t as insistent then as he is now about no photos, videos, or recording at his shows, but a full Super 8 camera was frowned upon. “The ushers were always watching,” Pagel told me. “One night an usher, a big guy, sat down on the aisle steps right next to me and I thought, ‘Uh oh. That’s it’.” The man smiled genially, took out a hash pipe, lit it, and offered Pagel some. Pagel happily continued recording, and we should all be so grateful that he did.

Mitch Blank, Bill Pagel, Robert Polito, and Barry Ollman in Tulsa

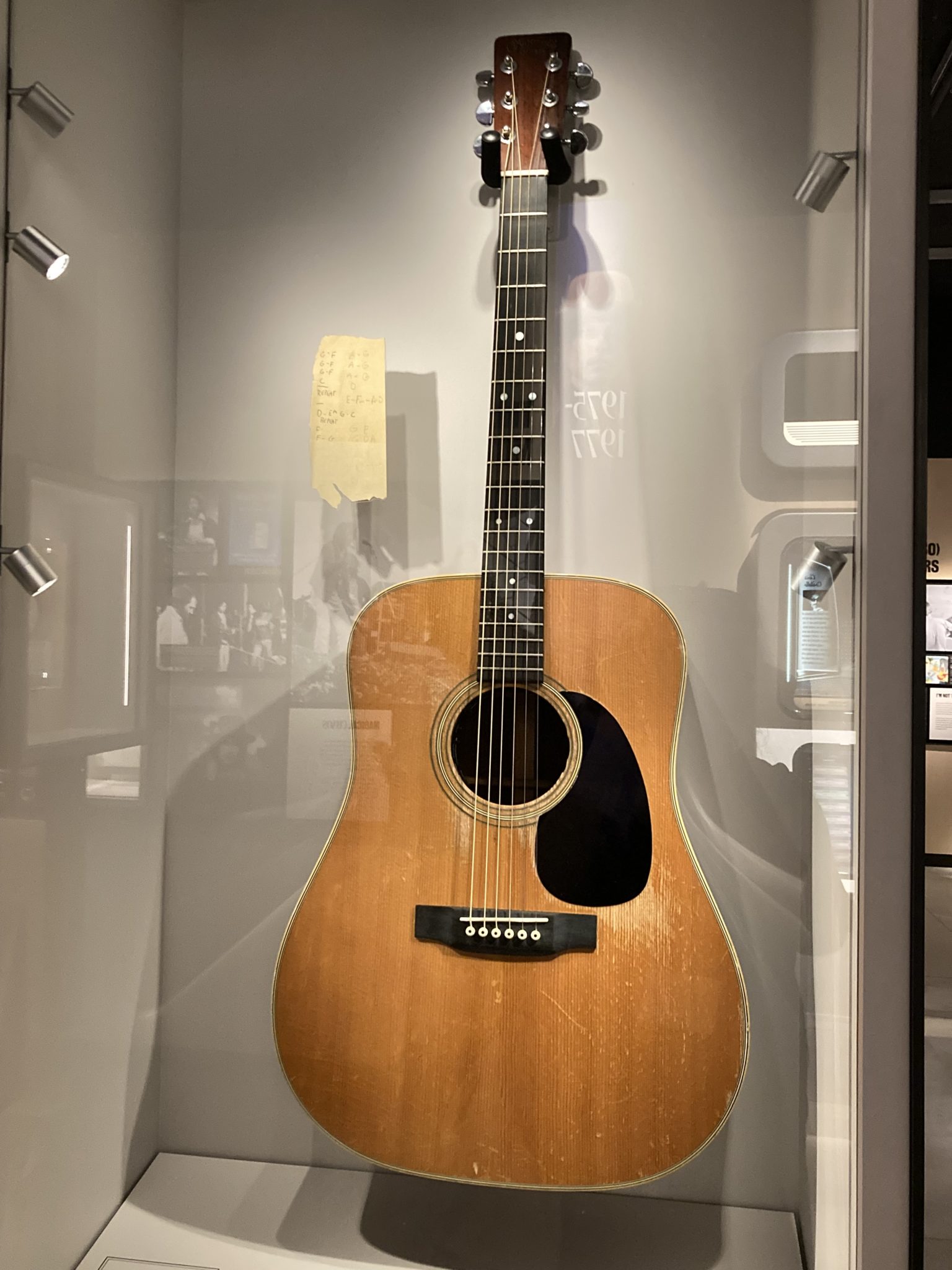

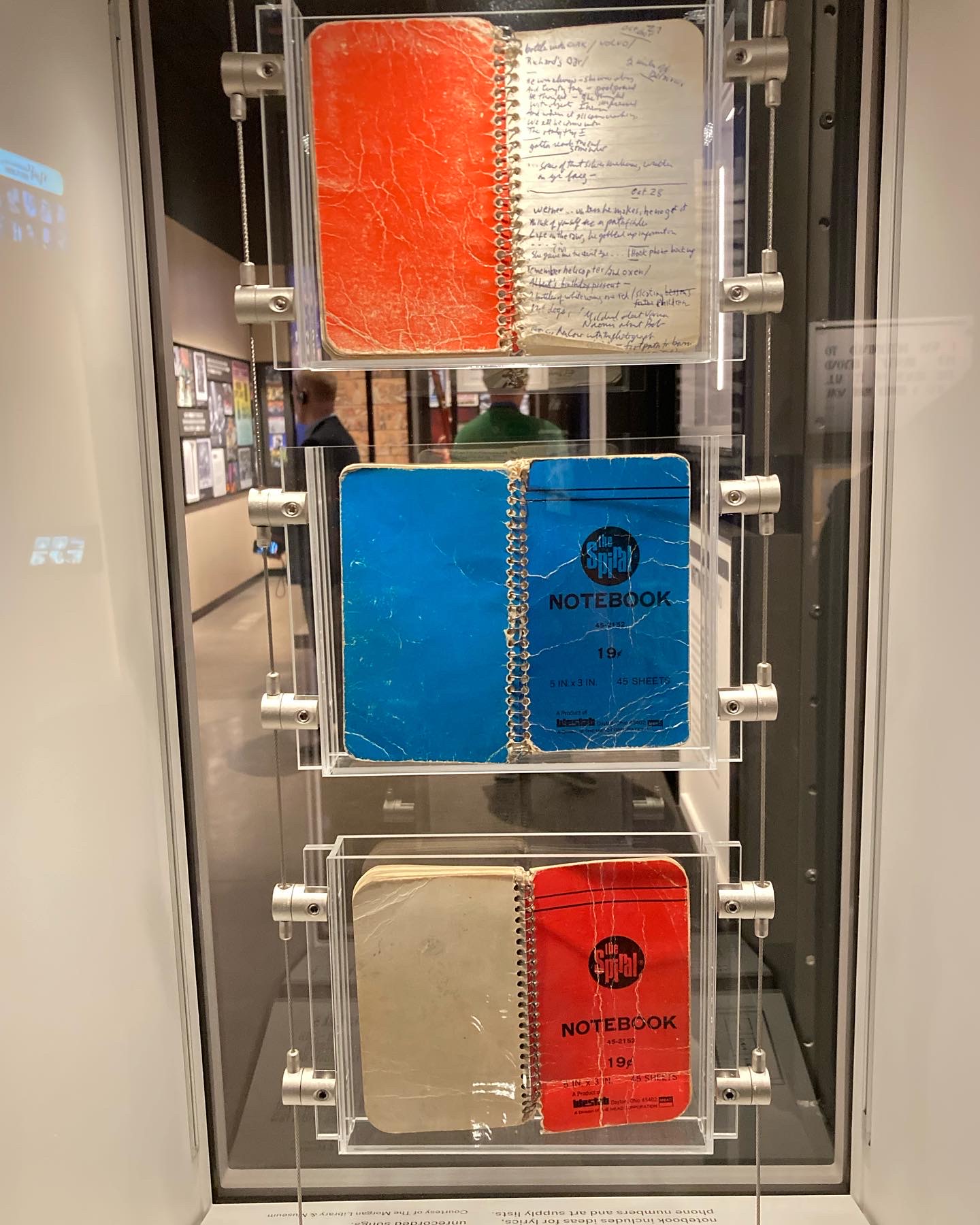

Also hailing from Minnesota is Kevin Odegard, born in Princeton on the banks of the Rum River. Odegard was 24, writing and performing songs of his own when he wasn’t busy working as a brakeman on the Chicago & North Western Railroad, when Dylan’s younger brother David Zimmerman invited him to a recording session at Sound 80 in Minneapolis, in December 1974. During a summer spent on his property in Minnesota, Dylan had written the songs for a new album in a series of three tiny spiral notebooks that cost nineteen cents each. He recorded the songs in New York in September, but redid them that winter, back in Minnesota during the holiday season. The album was released in January 25 with the title Blood On the Tracks, and that’s Odegard’s Martin D-28 that kickstarts ‘Tangled Up In Blue’ when you drop the needle on side one, track one.

Advertisement

Odegard donated his Martin to the Dylan Center in 2019. In town for the VIP weekend, he and Susan Casey hosted a coffee hour in the lobby of the Woody Guthrie Center — since the Dylan Center was not yet open — on the morning of Thursday, May 5. Dylan fans call this not Cinco de Mayo but Isis Day, from the first line of his 1975 song of the same name: “I married Isis on the fifth day of May.” We enjoyed our welcome, and then accompanied Kevin to the archive rooms at the Guthrie Center, where he was collecting some items he had loaned for an exhibition: his gold records and Billboard Magazine awards for his work on Blood On the Tracks. As they were being wrapped for him to carry, Odegard watched with a small smile, and suddenly made a decision. “Please keep them,” he said. “I’d like them to be in the Dylan Center.” The staff were thrilled, and we all applauded. “It’s where they belong,” he said happily, as we went back out onto the street together. Odegard’s book, with Andy Gill, A Simple Twist of Fate: Bob Dylan and the Making of Blood On the Tracks, is in the Dylan Center library, and I recommend it for yours.

Kevin Odegard’s guitar

Those three little notebooks bursting with the spinning, evolving words to some of Dylan’s best known and best loved songs are all reunited for the Dylan Center’s opening exhibition. One, which seems to me to be the last-created of the three as it is in places a fair copy of complete versions of some songs, has long been at the Morgan Library in New York. The “red notebook” was reproduced in the box set The Bootleg Series No. 14: More Blood, More Tracks (2018). In the autumn of 2018, I was the first scholar permitted to review the other two notebooks, which are in the Dylan archive, and wrote about them for Hot Press. Now the red notebook joins its baby blue and coverless fellows, on loan. They are arranged in order from top to bottom, the first to last, and seeing them in their case, open to the working drafts of ‘Tangled Up In Blue’, takes your breath away.

The Blood On the Tracks draft notebooks

Please don’t call the Dylan Center a museum. It is so much more than that. Yes, it holds heritage and conserves it for such ages as are left to us, but the vitality and vibrance of the place are palpable from the moment you walk in. Young Dylan, in a mural painted by Erik Burke and based upon a 1965 photograph by Jerry Schatzberg, welcomes you to a long brick building next to the Guthrie Center, with high ceilings and lights and color and sound. Designed by Olson Kundig of Seattle, with the exhibition space curated by 59 Productions of London, the Dylan Center reminds me of two things: the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon; and the TARDIS of Doctor Who.

Advertisement

Let me explain. The TARDIS is easy: the Dylan Center is bigger on the inside, packed with hundreds of thousands of documents, memorabilia, art, films, photographs and the people working on making them accessible to scholars and the world. It’s also a place where traveling through time is not only simple but encouraged, as you explore Dylan’s arts, and the stories they tell from 1941 to today, and the earlier things and people that shaped them. Like the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, the Dylan Center is designed for people with any and all levels of knowledge of the subject, from curious children and those who barely know the writer’s name to lifelong lovers and scholars.

The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust is on ground hallowed by William’s birth and death there, and the theatres and museums that sprang up because of him. The Dylan Center rests in an historic footprint crucial to America, and germane to one of the most American of songwriters — a cultural crossroads full of pain and blood, music and art, reconciliation and renewal. It is five centuries since Shakespeare’s time, and this country’s literary history is not so old, but people were here before white settlers declared this land “Indian Territory” in the 1830s, and resettled Lochapoka Muscogee Creek clan of Alabama here. The displaced Lochapoka called the place “tulasi,” or old town, and made lives for themselves here until the railroad came through. Then cattlemen and, soon, oilmen turned Tulsa into a boom town.

The vitality of new Tulsa in the Greenwood district, along the railroad tracks in town, was fueled by African-American businesspeople and musicians until the horrific “Tulsa Race Riot” of 1921. Not a riot but a massacre, it was a murder of more than 300 people and the destruction of what had been called the “Black Wall Street” — cultural critic and Dylan scholar Greil Marcus rightly dubbed the dark days “the Tulsa pogrom.” The Dylan Center sits in the heart of the once-ravaged neighborhood, and not only acknowledges but celebrates the history and heritage of famous kindred spirits and local musical heroes like Woody Guthrie (whose songs inspired Dylan in his earliest days), JJ Cale, and Leon Russell (both men Dylan’s friends, who performed with him), but also those people whose names are now lost, who were pushed out and killed, and who shaped this place.

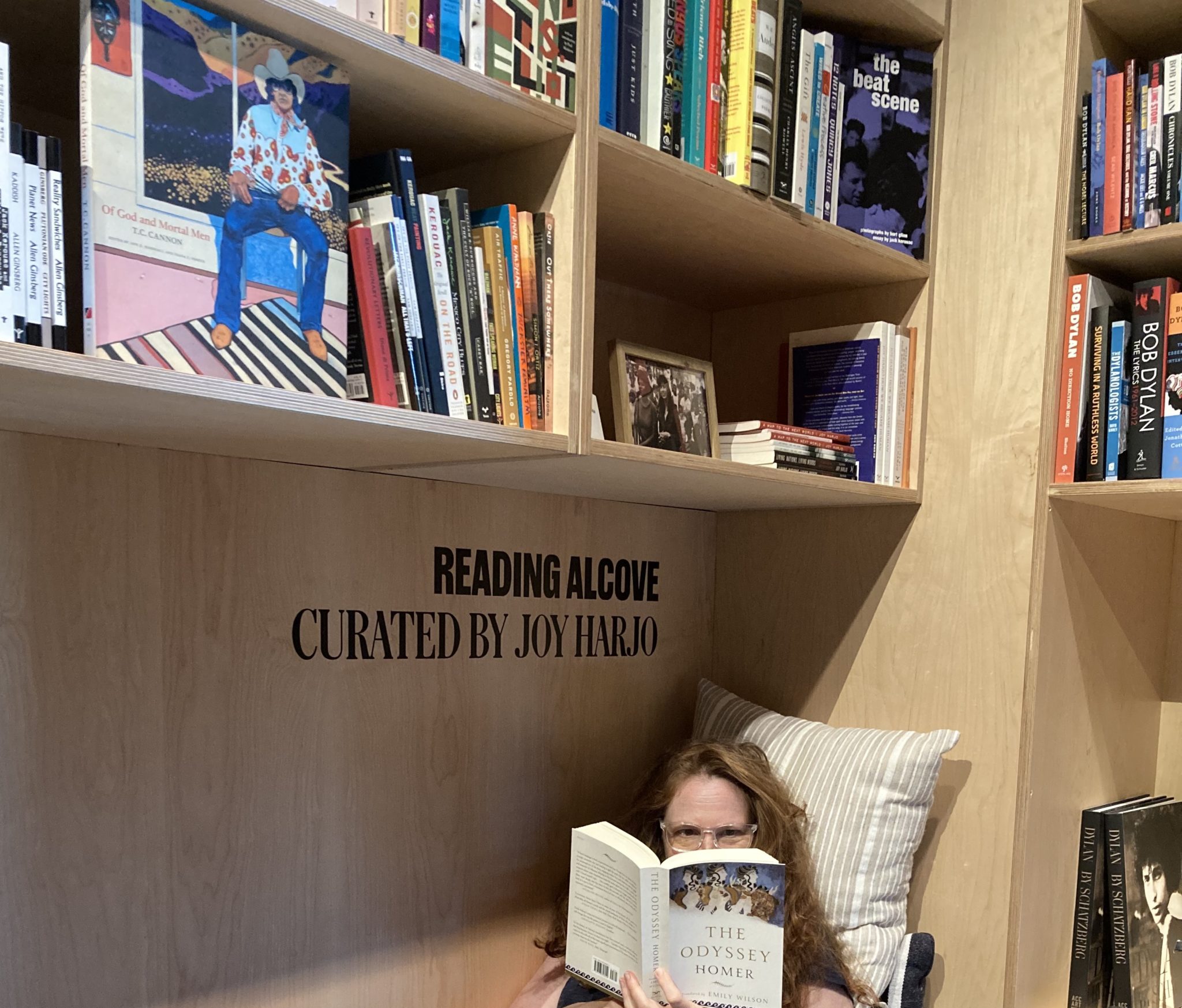

Reading Alcove curated by Joy Harjo

Joy Harjo, born in Tulsa 70 years ago to a father of the Muscogee Creek nation and a mother with Cherokee heritage, is the United States Poet Laureate and a gifted musician. She is also the artist-in-residence at the Dylan Center. A photograph of Harjo taken by Allen Ginsberg in 1982 smiles down in the Reading Alcove she has created for the Center. It is full of books about Dylan, Tulsa, American history and literature, and Dylan’s influences. Walt Whitman, Ovid, and Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey of Homer are here — as are the works of the man perhaps most influential on Dylan, who once jocularly referred to him as “Will the Shake” and who was the first writer Dylan thought of upon receiving news of his Nobel Prize in Literature. Connections and inclusion are what the Dylan Center is about, and you can literally see and feel it every step of the way through the building.

Advertisement

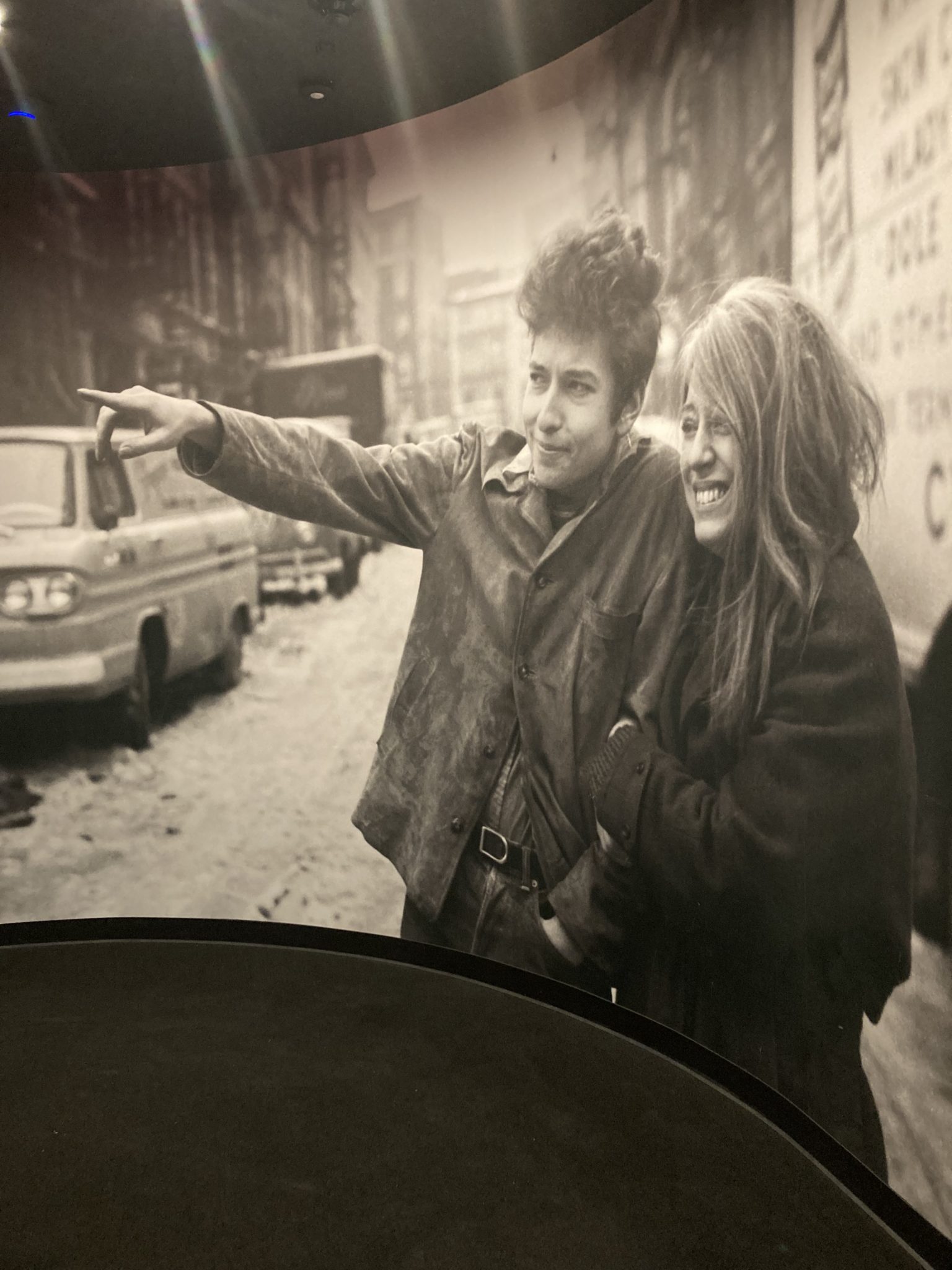

Bob Dylan and Suze Rotolo, February 1963

Don Hunstein’s portrait of a 21-year-old Dylan and his 19-year-old partner Suze Rotolo, an outtake from the sessions on the streets of Greenwich Village that produced the cover for The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), welcomes you to the show. The photographers who documented Dylan’s life and career are generously acknowledged throughout: Barry Feinstein, whose images of Dylan are my favorites; Schatzberg, who shot the cover of Blonde On Blonde; Lisa Law, who photographed Dylan in Los Angeles in 1965 and 1966. Feinstein, who would now be 92, died at home in Woodstock in 2011. Schatzberg, 94, lives in New York and could not attend the opening, but much of the second floor of the Dylan Center is currently devoted to an exhibition of his work. Law, 79, walked through the Dylan Center elegant in a feathered hat, greeting well wishers and old friends alike. Her photographs of 1960s “counter-culture,” now part of the mainstream of American history, bear witness to her continuing activism and art today.

The stairs between floors of the Dylan Center]

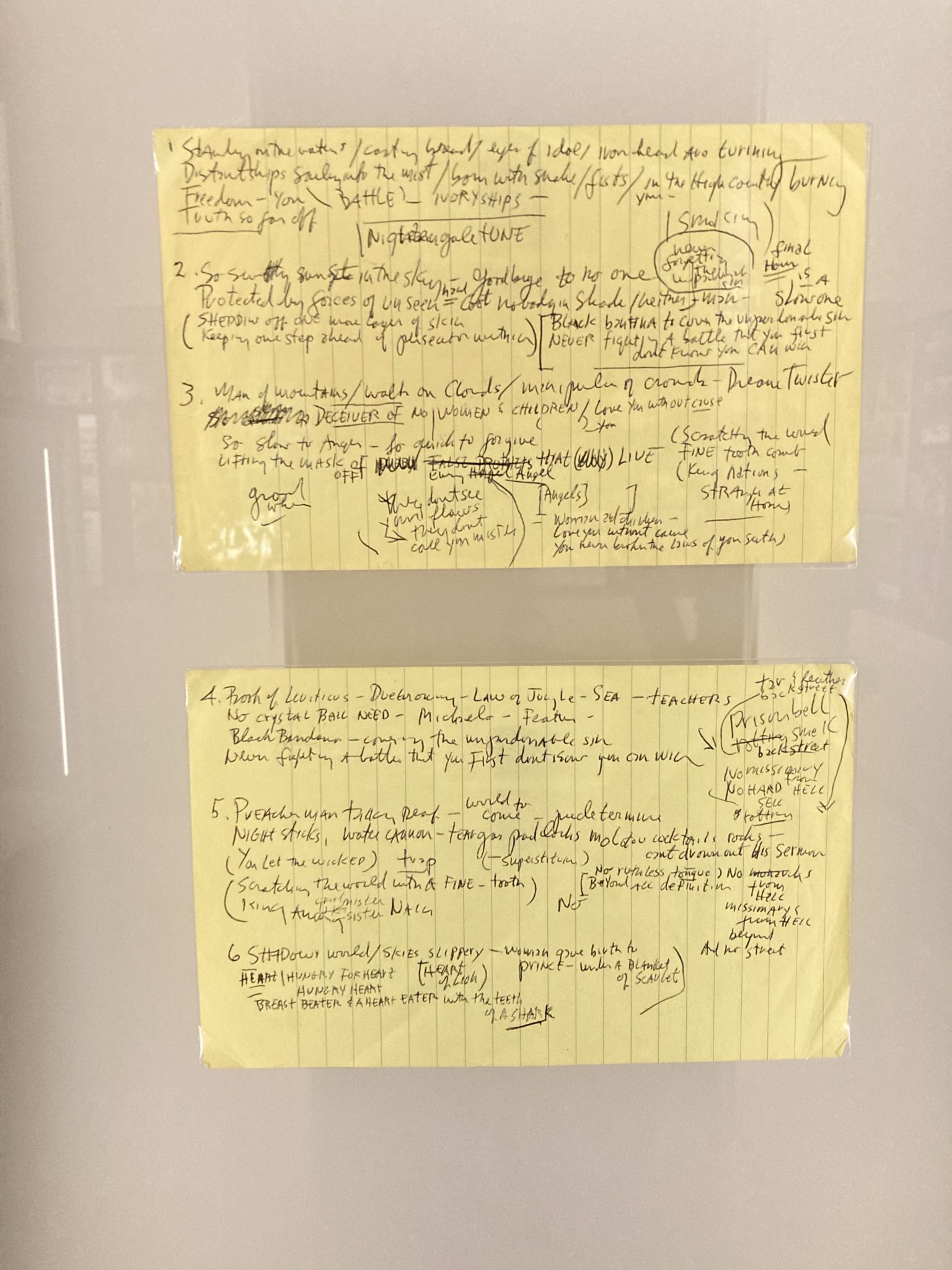

The contents of the main exhibition have been shared widely online. Trust me, seeing cellphone photographs of Dylan’s drafts for ‘Jokerman’ and ‘Tangled Up In Blue’, or clips from the home videos taken at Albert Grossman’s home in Bearsville, are no substitute. Come to Tulsa for the films of Dylan shimmying down a wall on a New York City rooftop, arranging himself and his acoustic guitar with its snarled metal spaghetti of uncut string ends for John Cohen; of Dylan on his motorcycle pumping gas for himself, then cruising along Rock City Road in Woodstock; of Dylan and Richard Manuel and Rick Danko playing cards. Come for his gray suit from Masked and Anonymous, the leather jacket from Newport. Most of all, though, come for what a working archive means to scholars: the manuscripts of his songs and other writings. You can see what is in the exhibition. To work with the materials housed in the archive, one must follow the procedures in place at every rare books and special collections library or archive at which I’ve ever worked: identify what you want to see, fill out an application for same, and supply your academic credentials. If approved, you’ll be given an appointment. What is on show is an overwhelming sample of the Dylan archive; let it be your guide to thinking about what you would like to apply to see in the future.

Some of the drafts for the song “Jokerman”

Advertisement

The VIP weekend featured three concerts by three old friends of Dylan’s: Mavis Staples, Patti Smith, and Elvis Costello. All the shows were at Cain’s Ballroom, that cathedral of music, a vast wooden quonset hut built in the Jazz Age as a garage for a rich man’s cars. The rich man, W. Tate Brady, was a lawyer whose name was once on the streets and theaters and neighborhoods of Tulsa. However, Brady was also a member of the Ku Klux Klan. In the 2000s, his name was removed from many places. During the 1930s, Brady’s former garage became a dancehall thanks to its new owner Madison Cain, and the Ballroom was for many decades the home of Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys.

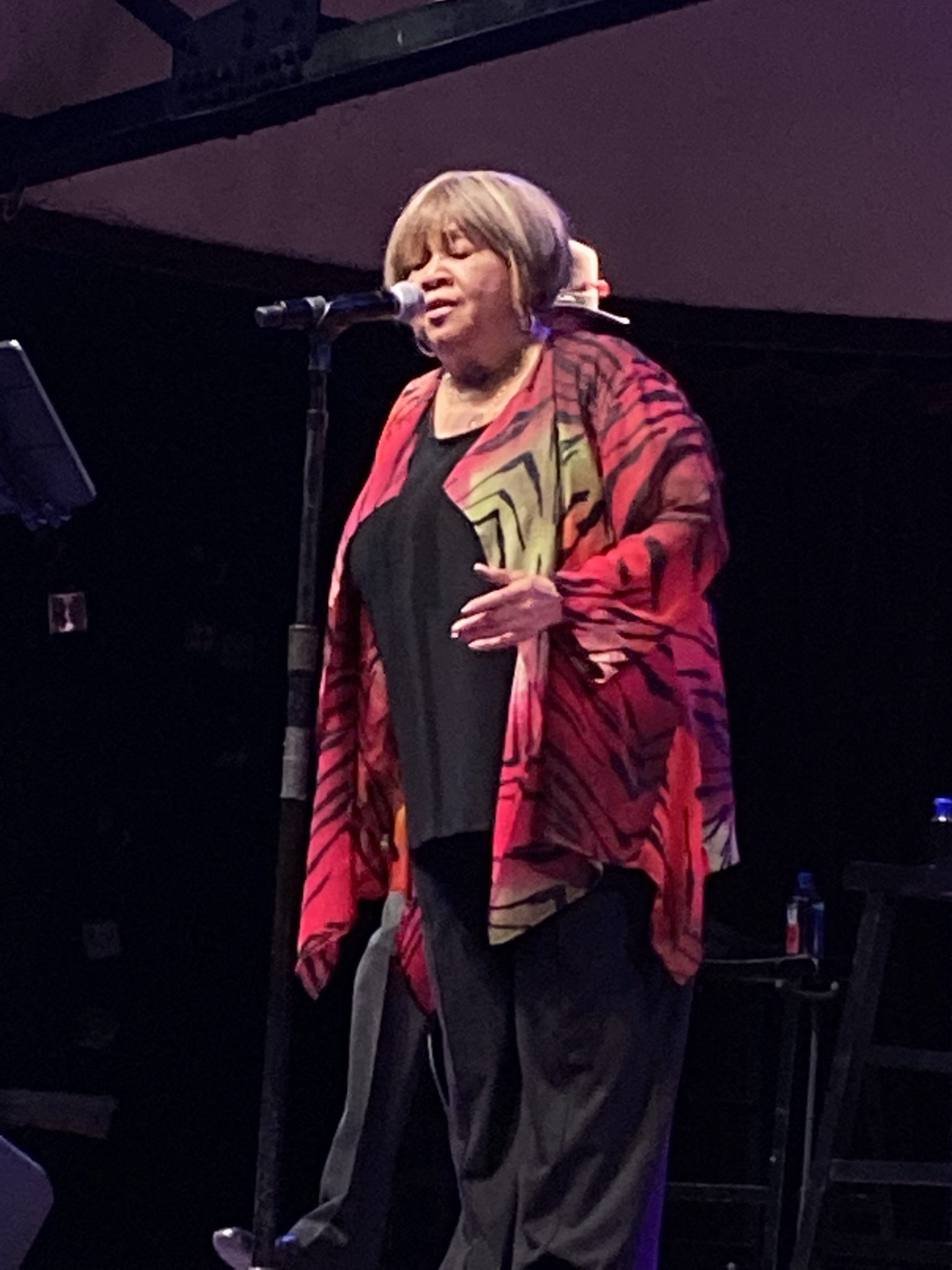

Staples played the venue after an afternoon visit to the Dylan Center, during which she lingered over cases, and often her rich, warm laugh — truly chicken soup for the soul — sounded out. Exclaiming over them with real affection, she seemed to particularly enjoy his childhood and high school photographs from Hibbing, and a portrait of him by Arthur Rosato taken outside a record store in Portland, Oregon in 1980. “He looks pretty slick here,” she giggled admiringly. In front of the Blood On the Tracks notebooks, Staples marveled over the tiny handwriting, and said she was about to cry. “So beautiful,” she proclaimed the Dylan Center, a beautiful thing done for Dylan and for us all.

Mavis Staples at Cain’s Ballroom

Mavis Staples is now 82, and every bit as beautiful herself as she was when she sang with her family in The Staple Singers, from the time when she was just a girl. Few performers have such an embracing and healing energy. She called for us to vote and to always, always fight for voting rights for all. She remembered her father, the great Roebuck Staples, and her family and their 75 years of performance and civil rights activism. She sang that great anthem she performed with the Staple Singers and The Band at The Last Waltz in 1976, and so many times before and since, ‘The Weight’. Cain’s is a dancehall, and we used it for same all weekend, have no doubt. As Staples and her superb band, led by guitarist Rick Holmstrom, finished their show, we all danced with her to ‘I’ll Take You There’.

In 2011, Staples came to visit her longtime friend Levon Helm and performed at a Midnight Ramble with Helm’s band, including her goddaughter, Levon’s daughter (with singer-songwriter Libby Titus), Amy Helm. The recordings from that night and the days she spent in Woodstock will be released on May 20; the album is called Carry Me Home. Don’t miss it, and don’t miss Staples on the road this summer, when, for some of her concerts, she will be accompanied by Amy Helm.

Advertisement

View this post on Instagram

Patti Smith posted joyful photographs of herself in the Dylan Center on her Instagram account @thisispattismith, an account that is one of the sole pleasures of so-called social media. Smith has known Dylan since writer Lucian Truscott IV, who knew both, introduced them at The Bitter End in 1974; she was selected to perform at Dylan’s Nobel Prize ceremony, and did so with both appropriate nervousness and sheer grace. Smith and her band, with Lenny Kaye on guitar, began their set with a lovely ‘Boots of Spanish Leather’. Kaye, a fine music writer, did a reading from his Lightning Striking: Ten Transformative Moments in Rock and Roll at Magic City Books while they were in town. He has played with Smith since 1971, and has been in her band since 1995; their history together makes their performances something more than special. Smith returned to Dylan’s songs throughout the show, with ‘Wicked Messenger’ standing out thanks to the contributions of her son, Jackson Smith. Calling out the spirit of Dylan in Tulsa, Smith joked that he wasn’t really here, but then paused, and corrected herself. Arms akimbo in that including, welcoming gesture of hers, Smith said happily, “He’s every fuckin’ where.”

Costello came through the Dylan Center trailing an entourage of every reporter with media credentials for the event, and there were many. Everyone wanted a piece of Elvis, but Elvis just wanted to look at the draft manuscripts. That night on stage at Cain’s, he told the story of meeting Dylan for the first time. Having used someone else’s name to get into a Dylan gig in the late 1970s, and then been outed as himself, Elvis was summoned backstage with a friend. “I been hearing about you,” Dylan said to him. Elvis shook his head in self-deprecation as he recalled his first words to a man whose music he so admired: “I’ve heard a lot about you, too.” Like the other bands performing this weekend, Elvis Costello and The Imposters did a selection of Dylan’s songs, with passion and gratitude. ‘I Threw It All Away’ was heartbreakingly good, and ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ shook those old wooden walls. Charlie Sexton, the guitarist who for many years was in Dylan’s traveling band, is now supplying his fire to The Imposters. It was great to hear him singing along on songs which for so many years I’d only heard him play. Pete Thomas, one of the best drummers in the business, Steve Nieve on keyboards, and Davey Faragher have played in The Imposters since 2001; Sexton is a gorgeous recent addition (2021) to the band, and long may this lineup continue. The cuts they performed from their most recent album, The Boy Named If (2022), show Elvis’s current power. ‘Magnificent Hurt’ was just that. And the old songs they did brought cheers and tears: ‘Alison’, ‘Watching the Detectives’, and what may be the finest ‘Pump It Up’ I’ll ever hear and stomp-dance to.

Elvis Costello at Cain’s Ballroom

Advertisement

This hot, sunny morning in Tulsa, my feet hurt, and I think I have a pulled muscle that clings to my left shin. Thanks, Elvis, you old punk deity, you. All the best with the rest of your tour, and safe trails to Memphis to you and your solid gold band. The Mayfest is still going strong this weekend, with local painters and ceramicists and jewelers selling their wares in booths along the closed streets, and concerts all-day-long, outdoors on Guthrie Green. Most of the folks who came to Tulsa for the Bob Dylan Center’s VIP opening weekend have headed for the airport now, or are on the roads back home, driving out of this town through the sweet strong constant winds off the prairies.

Me? I’m going to have another coffee at Chimera, on Main Street, where I am sitting and writing, and then I will walk slowly down Reconciliation Way, drawn, inexorably, back indoors even on such a beautiful day. Come to the Dylan Center soon. It is open from May 10th for the future that we can foresee.

Bob Dylan in a movie still from the “Jokerman” video

The Bank of Oklahoma building lit up to celebrate Bob

Advertisement

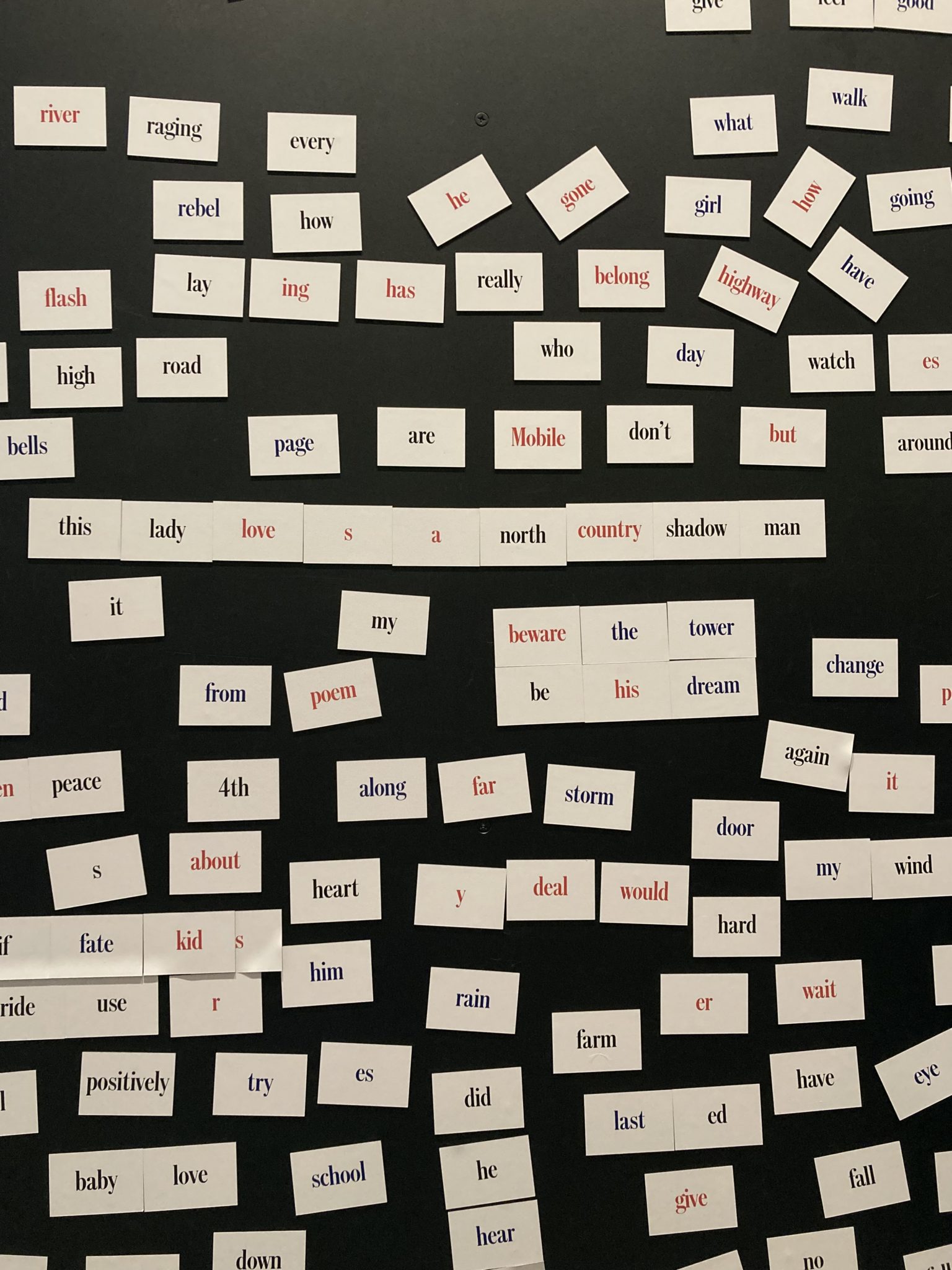

The magnet board for visitors at the Bob Dylan Center

Anne Margaret Daniel 2022

• All photographs by Anne Margaret Daniel for Hot Press unless otherwise indicated

All Bob Dylan lyrics © Babinda Music 2022

Images © The Bob Dylan Center