- Opinion

- 23 Apr 21

You Should Have Heard Them Just Around Midnight

It starts with the riff, as it almost always does. A slash from the fourth to the root, and then, an octave down, from the root up to the fourth. A second guitar, the drums, and a bass all heave in. There’s an unexpected Eb chord. An acoustic guitar wakes up in the other channel. After thirty seconds the singer leans in over the next-door fence and starts gossiping. It’s one of the most exciting half a minutes in rock n’ roll, conjured up by way of some particularly dark arts, a spell cast to make human beings move. You may have seen it performed in stadia by aged men, peddling welcome nostalgia – and peddling it well, you may have heard it a thousand times through speakers great and small, but it retains its lustre, as if it were wrought this very morning, and not some fifty years ago.

‘Brown Sugar’ adds irrefutable evidence to the case for The Rolling Stones as the greatest rock n’ roll band of all time. And I do mean all time, for it seems more and more unlikely with each passing year that we’ll ever see anyone even close to their like again. You could just as easily point at anything The Stones recorded from ‘Jumping Jack Flash’ up to Exile On Main St - and I would add 73’s Goats Head Soup to that pile, although many would argue that point. It is the greatest artistic purple patch in history; it might just be the greatest thing in history, full stop. Yes, there are a lot of nice paintings hanging up out there, Shakespeare had some good lines, there’s no denying it, democracy sounds good on paper, and modern medicine is a thing of wonder, but do any of them rock like The Stones?

Released as a single on April 16, 1971 and the opening song on the band’s ninth studio album, Sticky Fingers, out a week later on the 23rd, Brown Sugar’s verses clang from C to F while Charlie Watts beats the living shite out of the floor tom behind them, then the band crash into G for that chorus that everyone knows even if they don’t know it. There’s a barrelhouse/whorehouse/outhouse piano tinkling in the background, courtesy of Ian Stewart, happy to sit in because there's no minor chords, and a saxophone parps down near the basement during the second verse. Keith Richards once told someone that the secret to a good single is to introduce something new every thirty seconds. Set your watches.

The sax break sounds like Bobby Keys has just stepped out of a particularly boisterous knocking shop to honk about what’s going on inside. In response, Jagger starts swinging his maracas. “Yeah, Yeah, YEAH! WHOO!” Not for the first or last time, Keith doffs his cap to his forefather Chuck with the round out riff and, when the whole thing clatters to a halt, he offers a satisfied “Yeah!” because he knows, that yet again they’ve captured lightning in a bottle. Let me quote my wise Auntie Zena, who described it to me recently as “powerful magic”. She knows what she’s talking about.

Advertisement

The lyrics reference slavery and – more acceptably – cunnilingus, and there may be some heroine in there too. While there has been outcry, the surprising thing is there hasn’t been more of it. Jagger has always claimed he wrote it in a hurry, but this was an educated man in his mid-twenties. He knew what he was doing. He was the king of the world, the most famous – certainly the most notorious – rock n’ roller of them all. My guess is he was playing up to that. We should be glad, I suppose, that he at least saw fit to change the original title, ‘Black Pussy’. As one might expect, he has tempered those lyrics during subsequent live performances and has said, several times, that there’s no way he’d write or indeed get away with writing anything like that since. No one would.

Let’s put it another way. In 1971 The Rolling Stones were the most famous rock n’ roll band in the world. Ten years before that, rock n’ roll was nearly dead, the originators were all in various states of distraction, and brylcreamed dreamboat crooners ruled the day. Ten years after this we would be into the eighties and heading towards the homogenisation of rock n’ roll in the wake of Live Aid, as noble a venture as it was. Therefore, The Rolling Stones taking a song that gleefully waved two fingers at every taboo it could think of all the way to the top of the American charts must represent some sort of pinnacle of rock n’ roll as a truly subversive, truly counter cultural force. By all means, be offended by it but at least acknowledge that they were refusing to play it safe. It didn’t last. Only a few years later Jagger himself would be declaring that “It’s Only Rock N’ Roll”. Mind you, none of that would matter in the slightest if the thing didn’t rock like a bastard. It’s a vital, life-affirming noise, because rock n’ roll at its best isn’t “only rock n’ roll”. It’s so much more than that.

If you were at home in front of your record player in April 1971 and you flipped the seven inch over, ‘Bitch' was very nearly as good again. The story is told, by engineer Andy Johns, that Keith was late to the recording session and the others were playing around with a riff that was going nowhere fast. Richards arrives, sits on the floor to eat a bowl of cereal, calls for a guitar, kicks the song up several gears and that was that. It’s been pointed out many times that The Stones follow Keith's guitar rather than Charlie's drums, unlike every other band. You can hear what that means in ‘Bitch’. It's driven by that guitar riff, doubled by Jim Price’s trumpet and Bobby Keys’ saxophone, but when Richards veers into his solo, he pulls the beat out of shape, turns it around, and Watts falls in behind him. Many, many bands have tried to cover The Rolling Stones. Perhaps you were in one of them? Precisely none ever got it right, because they didn’t have Keith Richards and Charlie Watts. Maybe they had a drummer as good as Charlie, although I doubt it. Maybe they had a guitar player with a sense of rhythm as unique as Keith’s, although this seems unlikely. Only one band ever had both.

Undercover

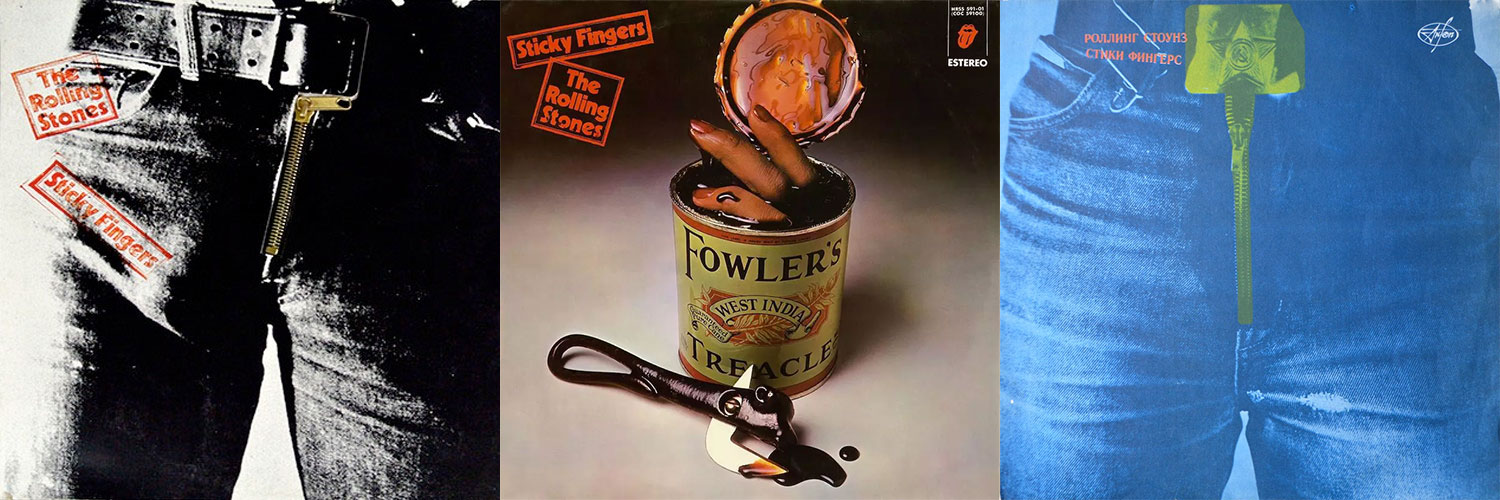

The album comes draped in what is probably The Stones’ most iconic record sleeve. While it was “conceived” by arch-chancer Andy Warhol, the donkey work was carried out by designer Craig Braun. Braun had helped realise the cover of The Velvet Underground’s debut, the one with the banana. The crotch shot – with something seemingly stuffed in the pocket – was rumoured to be Jagger himself but Braun says it was Factory hanger-on Corey Grant Tippin, although he did hear this from someone else. The initial zipper idea was Warhol’s, but it was up to Braun to make it work. It was he who argued with sceptical zip manufacturers that a Stones album would be a good thing to be involved with. Braun also encouraged the Warhol signature stamp – in order that potential customers might see it as a piece of art - that can be seen, when you pull down the zip and open the belt, on the y-fronts underneath – a photo of Interview magazine editor, Glenn O’Brien, apparently.

It is, if you will excuse the pun, a very attractive package, but there was a problem, the zip was damaging the records – the album itself and anything stacked beside it. They initially circumvented this by pulling the zipper down – of course – so the dent was in the centre of the record, where the track listing is, but it couldn’t last. The zip was replaced with a photo on later issues although it was back in place for the 2015 deluxe buy-it-again campaign.

Advertisement

Another first was the presence of the famous Stones tongue logo, designed by John Pasche, who gave up all claims to it for the princely sum of £26,000 in 1984. While it’s always associated with Jagger’s ample gob, the design is actually based on the Hindu goddess, Kali ("She who is death'). According to Braun, he and illustrator Walter Velez fleshed out Pasche’s initial design to what we first saw on the sleeve, and then everywhere else as it became one of the most recognisable trademarks in the world.

Not exactly famed for their sense of fun, The Franco regime in Spain weren’t having a cover like that in their shops so a bizarre alternative was offered for the Spanish market, with fingers emerging from a treacle tin. They also demanded the expulsion of the distinctly druggy ‘Sister Morphine’. It was replaced by Chuck Berry’s ‘Let It Rock’, recorded live at Leeds University on March 13, 1971. It is, alongside ‘Little Queenie’ on Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! and ‘Bye Bye Johnny’ on The Rolling Stones E.P. from 1964, one their best Berry covers, and there have been a few. If you’ve any sense, you’ll shell out for the super deluxe version of Sticky Fingers – if you can still get it – which will make you the proud owner of the entire Leeds gig and the envy of all your friends.

One final cover-related titbit: there was a Russian release with a prominent hammer and sickle design on the belt buckle. The person wearing the jeans is now either female or a male who’s suffered a very unfortunate accident. Make of that what thou wilt.

The Pavlovian Dog With Two Mickeys

After ‘Sugar’ comes ‘Sway’, and it’s around about this point that you realise Sticky Fingers is an album of the two Micks. Mick Taylor joined the Rolling Stones in 1969 having graduated, as others did, from John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. He was brought in as a replacement for the laid off Brian Jones and his first performance with the band was in front of some 250,000 people in Hyde Park shortly after Jones’ death. You can hear him on a track or two on their 1969 album Let It Bleed, you can hear him on the ‘Honky Tonk Woman’ single from the same year, and you can certainly hear him on the previously mentioned Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! live record but Sticky Fingers was his first full-length Stones studio outing and it’s one that could not have been the same without him. It is his virtuosic playing that lifts ‘Sway’ – two solos, one with slide, one without, the jaw-dropping improvised second half of ‘Can’t You Hear Me Knocking’ and the closing ‘Moonlight Mile’. He didn’t receive a single song writing credit – where does arranging end and song writing begin? – and nor wold he on later songs like ‘Time Waits For No One’. This shafting would be no small factor in his decision to leave in late ’74. The Stones were sometimes great after he left, but they would never be as great again.

In the same way that Exile On Main St. would belong to Keith Richards, Sticky Fingers belongs to the other Mick, Big Mick, Mr Jagger. While ‘’Brown Sugar’ might be three and three quarters of Keith’s finest minutes, the song, including the riff, was written by Mick, and ‘Sway’, ‘Dead Flowers’ and ‘Moonlight Mile’ all sprung from the same pen. He has never received enough credit for his prowess as a singer, for of all the voices that were first heard in the sixties, his was the one that most successfully incorporated the various strands of American music and came up with something of his own. He never sang better than he did during these sessions either. Too often he would slip into self-parody in the years that followed but here, howling out ‘Brown Sugar’ and ‘Bitch’, straining in the chorus of ‘Can’t You Hear Me Knocking’ and delivering real soul in ‘Sway’, ‘Wild Horses’ and ‘Moonlight Mile’, he is at his most focused. The Disciples of Keef, who are legion, always claim that Richards is the soul of the Stones, the keeper of the flame, while Jagger is their salesman, and I was guilty of this too, as a younger, dumber man. Every cliché has a grain of truth in it, but there are two of them in this partnership and, while there's been some admirable solo work, theirs is a shared immortality.

Advertisement

Throw Me Down The Keys

‘Wild Horses’, like ‘Brown Sugar’ and the album’s sole cover version, Mississippi Fred McDowell’s ‘You Gotta Move’, was recorded when the band stopped off in Muscle Shoals, Alabama during their 1969 US tour, the one that ended in disaster and death at Altamont. There’s a story that these recording sessions, captured forever in their great Gimme Shelter tour movie, took place on the quiet because they didn’t have the proper work permits, but the legend, like all good ones, may have been embellished since. What is certainly true is that in those rooms that had played host to Boz Scaggs and Cher before them, they captured something unique. They re-recorded ‘Brown Sugar’ later on, with Eric Clapton on slide guitar, but there was just something about those Muscle Shoals recordings, and it’s a shame they never went back. Though some graft took place at Olympic Studios, most of the remaining work on this album utilised the soon to be famous Rolling Stones Mobile Recording Unit in the comfort of Mick's country pile, called, appropriately enough, 'Stargroves'.

‘Wild Horses’ might just be The Stones’ greatest ballad, and it’s a true Jagger/Richards collaboration, with the melody and title coming from Keith, and Jagger filling in the blanks. It’s also one of their most covered songs and this was how it was heard first. Because of their on-going legal tussles with former manager, Allen Klein, the man who also famously got his hands on The Beatles, these songs were held back. Klein’s company, ABKCO, still co-owns the rights to them, which is why you see them pop up on ABKCO compilations along with all the Stones 60s material. When he asked, Jagger gave his blessing to Gram Parsons to record a version with his band The Flying Burrito Brothers for their second album Burrito Deluxe, which would come out a year before the Stones' definitive reading. Featuring a high and lonesome Parsons vocal and a beautiful bit of piano playing from Leon Russell, it is, alongside Linda Ronstadt’s run at ‘Tumbling Dice’, one of the very best Stones covers.

Parsons, who became Keith’s new best friend, was certainly an influence on The Stones, teaching Richards the difference between the Nashville and Bakersfield sounds, but author Stanley Booth, whose The True Adventures Of The Rolling Stones is probably the best book about them, was a good friend of Parsons and he dismisses any notion that Gram might have helped with the writing. You can hear that country influence though, most especially in the way that Taylor’s acoustic guitar employs what is known as Nashville tuning, where the bottom four strings are strung an octave up. Jagger has always claimed a love of country music but never thought it suited his voice. He saw himself as a blues singer, and reckoned Keith's croak had more country in it. ‘Wild Horses’ combines both of them for its glorious chorus. They lost something when they started employing outsiders to handle the backing vocals.

While we’re talking about country music, ‘Dead Flowers’ goes the other way altogether. Jagger plays it completely over the top, although not as much as he would on ‘Faraway Eyes’. Despite that, it still became a country classic, that even Townes Van Zandt couldn’t wring the joy out of, although his version that you can hear during The Big Lebowski has a good go. Taylor could of course play near perfect country licks because he was just that good.

‘I Got The Blues’ might be the greatest song Otis Redding and Steve Cropper never wrote. Richards always claimed that Otis recording ‘Satisfaction’ was akin to getting a nod from a god and The Stones return the favour here, not covering 'I've Been Loving You Too Long' exactly, but coming pretty close. Richards’ guitar is pure Cropper and Jagger, again, sings his arse off, playing it completely straight. Sticky Fingers is the album where they expanded their sound by letting others play along and Billy Preston’s Hammond solo injects just the right amount of melancholy, while Jim Price and Bobby Keys do their best Memphis Horns impression, adding as much to this song as they do to ‘Bitch’. There's brass on ‘Honky Tonk Woman’ but it's buried in the mix. This album is where Price and Keys earned their place, and they’d be all over the next one too. They, as much as anyone, helped to transform the band into the augmented rock and soul review we know today.

Advertisement

Satin Shoes & Plastic Boots

‘Sister Morphine’ originally surfaced as the B-side to Marianne Faithfull’s ‘Something Better’ in 1969, with her name down as co-writer. This mysteriously disappeared when The Stones released their version and Faithfull had to go to court to set things straight. The presence of Ry Cooder on slide guitar, who can also be heard on ‘Love In Vain’ on Let It Bleed suggests this must have been recorded around the same time. I could at this point go into the whole story about Keith Richards “stealing” the open G guitar tuning – the guitar is tuned to the chord of G allowing the player to add two fingers to go to C and Richards built his legend on these changes – from Cooder, but Cooder, as great as he is, has never written anything nearly as good as ‘Tumbling Dice’ so the argument seems a bit pointless to me. Anyway, ‘Sister Morphine’, a harrowing minor chord ballad with its references to various pills and powders, was the one that ran afoul of Franco, and you can perhaps hear why.

That leaves us with ‘Moonlight Mile’ and ‘Can’t You Hear Me Knocking’. The former is all Mick’s. There’s nothing else like it in their catalogue, a road song lifted higher by a beautiful string arrangement from Paul Buckmaster and one of Jagger’s greatest vocal performances. That’s Jim Price moonlighting, if you will, on the piano for the song’s moving denouement, he was a handy man to have around.

If you doubted me earlier when I claimed the combination of Richards and Watts as the defining factor that sets The Stones apart and above all other bands, then you only need to hear the opening bars of 'Can't You Hear Me Knocking' to know I was on the money. It would convert the staunchest of tone deaf anti-rockers to the cause. Jagger yelps his approval in the background as a riff as lean as a rake that's been wandering in the desert for forty days leers out of the speakers and makes straight for your girlfriend. Yes, the song goes off into a marvellous Santana-like jam featuring the talents of Keys and Taylor, but it is the push and pull between Keef and Charlie, with Jagger dancing across the top, that marks this out as one of their finest recordings. Put it on, turn it up and try not to get down, I dare you. The Greatest Rock N’ Roll Band Of All Time.

What did I leave out? We must, as we always must, take out collective hats off to the memory of Jimmy Miller, the producer who was there all the way through The Stones imperial period, before he succumbed to the devil's temptations. It was he who brought the magic out of them. We should also nod at the great Bill Wyman. Listen to his playing on ‘Brown Sugar’ or behind the extended solos in ‘Can’t You Hear Me Knocking’; he might have made the odd “error in judgement” when it came to matters matrimonial but he never put a foot wrong with a bass guitar around his neck.

Sticky Fingers was the band’s first album on their own Rolling Stones Record label and it presented the band for a new decade, at the top of the heap, nigh-on untouchable. It set in place the blueprint they're still working off. They continue to dine out, at restaurants that the rest of us wouldn't even be allowed to walk past, on the work they did here, and please god they'll be coming back to an enormodome near you sometime soon to play most of it before they finally hang up their hats. Yes, I prefer what they did next, because Exile On Main St is the greatest record ever made and I'll be back next year to tell you all about it, but Sticky Fingers is right up there beside it. One more time. Yeah, Yeah YEAH! WHOO!

Advertisement

__________

If you want more Sticky Fingers - and why wouldn't you - then let me recommend the great Will Russell's poetic analysis. I apologise to him for tramping over ground he's already covered so well, but sure I couldn't help myself, and I know he knows what I mean. I would also like to thank Dr David Fanning for allowing me to forge several of these notions in the crucible of spoof on his radio show.