- Opinion

- 27 Dec 20

THE 12 INTERVIEWS OF XMAS: Steve Lillywhite on U2, Boy, and All That You Can't Leave Behind

As part of the The 12 Interviews of Xmas, we're looking back at some of our classic interviews of 2020. Justifiably famed producer Steve Lillywhite has worked with everyone from Crowded House to XTC, not to mention the likes of The Pogues and The Rolling Stones. Back in 1980, he found himself in the West Of Ireland, watching a gang of four young hopefuls. “I could see there was something there,” he told Pat Carty in this interview, which featured in the Hot Press U2 Special Issue, published back in October.

Before we even get started, Steve Lillywhite cracks in with a yarn.

“Just let me tell you a very funny story. The band never listened to their albums, why would they? And because Boy was not such a big album, I don't think they really thought of it as being that good. But on the twentieth anniversary, they had to listen to a re-mastering or something. Bono called me up, ‘Steve, I just listened to our first album. It's fucking brilliant’. He was surprised, and I thought ‘yeah, it's pretty good’. He said, ‘I didn't realise at the time, it's great, but I'm not that sure about the singer!”

Lillywhite roars laughing, and we are off to the races.

I had listened to the Boy album in its entirety for the first time in a long time the night before we spoke myself, and Bono’s right, it is great. His vocals suit the material, but he wasn’t the thing yet that he would become.

“He's not the thing he became,” Lillywhite agrees, “and maybe Larry's not quite as tight as he became either. But Edge's guitar parts are great, and Adam certainly had some great bass lines. I was really, really proud of that album. I was especially proud because it was the very first rock album from Ireland, made in Ireland, that was successful. Because The Rats and Lizzy and maybe even Taste moved over to England to make their records. But U2 wanted to record it in Dublin, and I feel proud of that for sure.”

Had he heard of the band before he was approached to work with them?

“I was the up-and-coming young kid on the block," he remembers. "I had some hits with XTC and The Members and Psychedelic Furs, and I was well-known. I was one of these new young punk producers, along with Martin Hannett. I don't remember hearing ‘11 O'Clock Tick Tock’ [the U2 single that Hannett, famed for his work with Joy Division, produced] so much as hearing U23, which was the first E.P. I liked the voice, but it didn't sound very good, but something that I've tried to hold true my whole production life is I always want to see a band live. I can learn a lot more about them than if I hear their last recording, because when I see them live, I can think how I can approach it.”

The Crystal Ballroom

Come back with us now, to the Ireland of forty-odd years ago. The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

“I was flown over to the west coast of Ireland and I went to see them in this little school hall," Steve recalls. "All the boys were on one side and all the girls were on the other and U2 came out and opened with ‘I Will Follow’. I thought, ‘Oh my God, there's something about this’. We agreed to do a single first, which was ‘A Day Without Me’, which I didn't think sounded very good. I wanted to change the way that we recorded the band for the rest of the album, and it's quite well known that I decided to put Larry out in the hallway, where the receptionist sat in Windmill Lane, because the drum sound was just not very good on ‘A Day Without Me’, but the drums we recorded for the album were much more exciting.”

We’re getting slightly ahead of ourselves here: we still don’t know how the initial connection was made. Who approached Lillywhite first?

“I think it was the record company. But I remember I was told I would be met by a Mr. McGuinness at the airport. And this was Ireland in 1979, so I thought I'd be met with a guy with straw coming out of his hair, on a tractor, but it was ‘Hello, Steve, Paul McGuinness here’.”

Steve balances the stereotypes adroitly by putting on the kind of accent you might have heard in an Ealing comedy to impersonate former U2 boss. They hit it off.

“He was lovely, charming, and a salesman," he smiles. "Then we had forty minutes in the car, where he proceeded to play me all the band’s demos on his terrible car stereo system. They sounded dreadful. What I love about Paul McGuinness is that he has no real taste about the quality of music. He knows what he likes, but his job was to sell the band to me. And he thought the best way to do it was to play me these terrible demos. Really the best way would be to just see them live, but he's never thought like that, so he was playing these things and my heart was sort of sinking a little bit. But I saw the gig and went to see them afterwards. Bono was eighteen, and eighteen year-old boys don't have much of a personality. There was no sign of MacPhisto in those days. They were just drinking half pints of red lemonade shandy.”

This was a kind of exploratory mission, both sides feeling each other out, so to speak.

“You don’t have sex with someone who doesn't want to have sex with you - it was the same for both of us. We were seeing whether we wanted to shag each other,” Steve offers by way of explanation. “I was a little bit of a name, whereas they had become the big noise from Dublin. All the A&R rats from London flew over to Dublin to see a gig, which was terrible, and they all flew home going, ‘forget that band, they’re no good’. Six months later, they managed to get the deal with Island, but at that point, Island Records weren't necessarily the label you would sign to for a big push. McGuinness did a fantastic job, getting everyone on board, because Island had no other bands of anything like that ilk.”

Once Lillywhite saw U2 live, his mind was pretty much made up.

"Like everyone else at that time, I could see that there was something there - in the same way that Chris Blackwell saw it, and the same way that McGuinness saw it - so I was on board.”

Turn It Up, Captain

Apparently, Martin Hannett insisting on having some London equipment brought over to Dublin when he worked with the band in Windmill Lane. It was the best studio in Ireland at the time, but that didn’t necessarily mean it was the best studio for rock n’ roll.

“Well, it was very good for recording folk music, it was of the variety of studio that basically was very, very dead sounding,” Steve remembers. “Anything quiet sounded very good, but with anything loud, you just never felt the perspective of the sound. In those days, I was very much into sort of 3D sound, sound that went back as well as left and right. It was literally while I was walking through the reception - this stone room – that I thought ‘I love the sound out here’. But when I walked into the studio, the sound was just swallowed up.”

One might assume that when it came to this young band, the record company or even McGuinness himself might have offered some instruction to the producer, but this was not the case.

“The great thing about McGuinness is that he has never once questioned what the band wanted. If Bono says I want a lemon, McGuinness says how big? He never came to the studio. He never had an opinion about the music, his job was to sell, his job wasn't to criticise, and that's what I loved about him. And Island Records never had any influence on what we did. I was probably more in charge of the sound of Boy than any producer has ever been in charge of the sound of a U2 album, because they didn't know what they were doing. We were just bungling along, but I was definitely leading much more on that album than later on in their recording career.”

The role of the producer can sometimes be a mysterious one, but Lillywhite simplifies it.

“I was the captain of the ship, making all sorts of decisions about everything," he says. "I do remember once asking Edge if he had another guitar? And he said, 'No, I've only got the one'. We did a lot of bass overdubs and lots of different weird sounds. I think sometimes in those early days, actually it was after the October album, they could come across as a little bit ‘heavy rock’ live, but they never wanted a rock producer, and, obviously, after me, they went with Brian Eno. They always wanted something that was a little bit more art-based.”

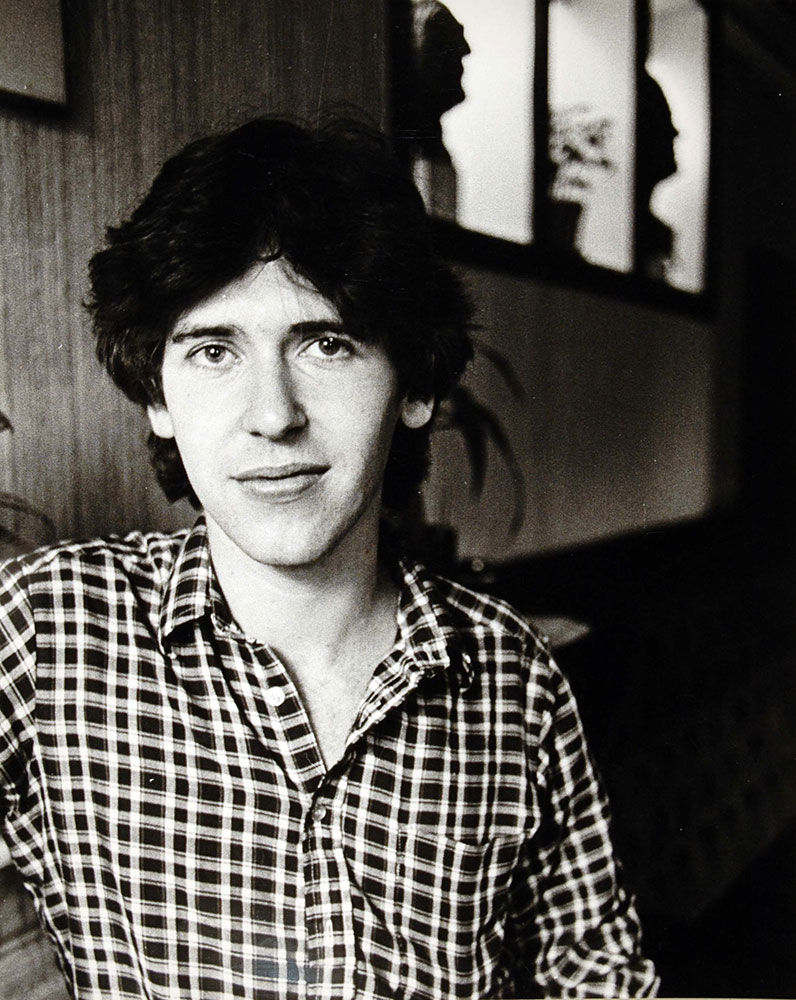

A Portrait, By Colm Henry, Of The Producer As A Young Man

A Portrait, By Colm Henry, Of The Producer As A Young Man“They were serious young boys," he adds. "One thing I've noticed with people I've worked with, who have gone from sort of nothing to really big, they normally get more paranoid as they get older. Whereas, with U2, it was sort of the opposite way around. When they were eighteen, they were really serious. And by the time they were double or older than that age, Bono was starting to become like his dad, a great guy and really funny. Adam was more the gregarious one, but the other three were very serious and into whatever they were into at that time. And, you know, we all know that.”

Like A Song…

The band were ready, the music was all there, although the lyrics were sometimes another matter.

“They had the arrangements down but Bono would change the melodies, and certainly, some of the lyrics had not been finished. Most people say you've got your whole life to write your first album, and I presumed that everything was written, but Bono still hadn't finished second verses and things like that. He was still experimenting, trying things out, singing in his phonetics, but never actually deciding what it was he was going to sing. I was young as well - I was only 24 or something - so it was all about pushing the envelope and using the energy.”

Surely the foot had to be put down? ‘Listen, Bono, the clock is ticking…’

“Putting the foot down with Bono is never the way to do it. Bono is the biggest pusher of Bono there ever was, but in those days he wasn't like he became, he was very intense. Most of the lyrics were done, but even then, there was a lot of discussion.”

There were financial and time constraints, probably, but Lillywhite wasn’t going to let those distractions bleed into the sound.

“It's a producer's job to deliver, to make an album. The first album should not sound like it was really laboured. It doesn't matter how long a record takes to make, as long as it doesn't sound like it took a long time to make. U2 should never sound like Def Leppard, because U2 have to have this sort of spirit and this spark and this joy that comes from the heart rather than the head. Def Leppard records are fantastic, but it's music that comes from the head. Like ‘Beautiful Day’, all he's singing is 'It's a beautiful day, don't let it get away' - but it works. And you think ‘why the fuck does that work so well, he's singing about the weather!’ but the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. And that's what U2 are always looking for.”

There was no ‘aren’t we marvellous’ playback celebration either.

“U2 have never had an album playback in their whole careers, as far as I'm concerned, because you're always working on it until the very, very end. So there's none of that listen to it, slap on the back. The band then went off on the road, and I carried on working because it was only a month, so I could do at least six or seven albums a year then. I did a lot of records in those days.”

Lillywhite can’t even say for sure if he felt happy about it at the time.

“I don't know,” he confesses. “I'd just done XTC and XTC albums was really easy, because they were fantastic musicians. They got everything really planned, whereas with U2, there - even right at the very beginning - was this wonderful Irish sort of untogetherness.”

Lillywhite slips into a stage Oirish accent here.

“’Ah, it'll be all right Steve!’ This is what I love about Ireland and the people there. It's all blagging, and they would admit to that!”

There is surely a lot of truth in that, to be sure, to be sure.

Staring At The Sun

The next time the band and Lillywhite worked together was at Compass Point Studios in The Bahamas. This was in April of 1981, when the band was taking a break after the Boy tour. The idea was to record the next single, ‘Fire’, but who would want to be cooped up in a studio when they could be arsing around in the sunshine?

“Yeah, that was a little bit of a letdown. And I don't think it was one of the greatest U2 songs. Although it's probably a bit better than “A Celebration”, right?”

I would argue it isn’t. I try to persuade Lillywhite to give up more information on the supposedly chaotic October sessions, but he’s having none of it.

“Hang on,” he shouts. “We're not talking about October! Come back next year for the 40th anniversary of October!”

Fair enough, hopefully we’ll have a vaccine by then and I can take the Hot Press Gulfstream to Jakarta to talk to the man in person. For now, I move on to All That You Can’t Leave Behind. As with The Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby, Lillywhite was brought in to help out as the album neared completion. It’s a different job from the one he had with U2 Mk I.

“On the first three albums, I was the main producer,” he explains. “I was in there from the very beginning. On Joshua Tree, they needed some help to finish it off. This is McGuinness' wonderful logic. He said, ‘Look, you made records with Steve in like six weeks or whatever. Why don't you get him to come in and try and help you finish it off?’ I've always called myself sort of the closer. When they see me, it's like, ‘Steve's here, we better get to work’ - like I was their teacher when they were 18. I just come in at the end, and I help them finish, but it's not just mixing it's more like a relay race. Brian Eno and Danny Lanois just pass me the baton and I pretty much run the final leg, but we all work equally hard on it.”

A set of fresh ears, because they've been at it so long?

“Exactly. I sort of have a little bit more of a commercial ear than both Brian and Danny. I think I have a balance between art and commerce. I remember ‘Beautiful Day’ was the first one I did, but I'll tell you a story about ‘Walk On’. After I finished ‘Beautiful Day', the band said they had two songs for me. One was called ‘Walk On’ and one was called ‘Home’. So I listened to both of those songs, and I thought ‘Walk On’ had a fantastic chorus, but ‘Home’ had a great verse. They said ‘that's weird because they used to be the same song’. The way U2 work a lot of the time, songs are like a tree, and different branches grow off the same song and another song appears. So with ‘Walk On’ we actually put them both back together again. I thought it was better to have one great song then two half songs and I was right because it won Song Of The Year at The Grammys. I love that album, probably for me that's either their second or third best album.”

Some Days Are Better Than Others

It should be noted here that All That You Can’t Leave Behind is the only album ever to have different tracks win The Grammy for Record Of The Year; ‘Beautiful Day’ won it in 2001 and, as Steve remembers, ‘Walk On’ won it in 2002. He worked on both songs - further proof, not that it’s needed, that Lillywhite knows his onions. Although it turns out that he hasn’t been that careful in hanging on to them.

“I don't have the cassette of ‘Beautiful Day’,” he admits. “That's the weird thing, but I do remember playing my wife at the time a cassette and saying ‘this is what I'm working on, this is the first single’. She worked at MTV, so she had good music ears, but she wasn’t sure this was going to be the song to launch them back after Pop, because Pop had not really been such a commercial success, but I don't know where that cassette is. I've thrown away handwritten lyrics by Bono, so I'm not a hoarder; I'm not someone who keeps anything. But obviously ‘Beautiful Day’ became better and better when we were working on it.”

It would seem that the Lillywhite hit single sheen is what the band are after.

“They know which ones have at least single potential. And so that's what they give me. They gave me ‘Where The Streets Have No Name’ and ‘With Or Without You’, so ‘Beautiful Day’ was the one. On How To Dismantle An Atomic Bomb, I had yet another job because that was the only time they've actually let the producer go, but that's for another interview, Pat. Oh My God, I can't give you everything!”

He calms down. A bit.

“It's the same job I've done - post War - on everything except for How To Dismantle An Atomic Bomb, which is a few albums – The Joshua Tree, Achtung Baby, All That You Can't Leave Behind, No Line On The Horizon. It's a good job and I like it, but whether it will happen again? Probably not, but hey, I've known this band well over half my life and they're just great. I love them.”

How about this? The phone rings next week and it’s Bono saying he’s needed in Dublin. Would Lillywhite go?

“It depends on the... Yeah, of course I would. I've had that phone call many times. I had the phone call for the last one. I mixed it in Jakarta as that's where I live now, in Indonesia. It was a pretty good album, but it didn't really have that huge song on it, though.”

Another Time, Another Place

As even the most casual music fan might be aware, Steve Lillywhite’s name is on an awful lot of records, so does the fortieth anniversary of Boy mean a lot to him?

“It means a lot to my knees because when I stand up I'm all creaky,” he jests. “No, it's fantastic. I've been involved with a few albums that that have that sort of milestone element to them. I'm very proud of my catalogue.”

With the commercial success of War, there must have been other bands that wanted that big U2 sound. Lillywhite said no.

“I never worked with another band who wanted to sound like U2. Obviously U2 spawned a lot of sound-alike bands, certainly with guitarists who had that jiggedy-jiggedy sound with the delay. I always said no to them, and that's why I've had such a long career, I think, because whenever I've had success with an artist, I've always used the success to expand the sort of music I did rather than do the same thing.”

Semi-retirement would appear to suit the great producer just fine.

“I think I've decided that it's a different world now,” he muses. “Producing is much more about teams who sit around the computer. It’s not about musician interaction so much anymore. I'm not complaining about it, I'm just saying it's not my era anymore. What I'm trying to do is, I suppose, monetise my past. I'm writing a book, I actually do a sort of stand up routine, which, before COVID, I was planning to take around the world. It’s basically playing a lot of music and telling stories. I do bits of sad things with Kirsty and I do some Pogues stuff, and U2, and, and all the artists I've worked with. It's a two hour show, and I've done one performance of it, and then fucking COVID stopped me, which is a drag, but when COVID is over, that's my plan, finish the book and tour the world with it.”

More explanation is offered.

“Producing is like a muscle," he continues. "If you don't do it all the time, then I'm not sure whether I can be as good, and why would I want to? I don't want to ruin my reputation. I think a lot of artists make albums when they don't need to. Paul McCartney and Elton John, as much as I love them, I think they maybe made too many albums.”

But if a good band did get in touch, with worthwhile material, could he be tempted back into the ring?

“Sort of like Rocky? I'll go back for one more fight! I have a different life now, and it's great and I don't want to ruin anyone's career either. I don't have an ego. Well, I do have an ego, but I only do things for the art. So maybe if something that really excited me came along, then maybe I would do it.”

Stories For Boys

As I’m sure you can tell, Lillywhite is in good form, so I take my chances and throw out a few more ‘2 related inquiries. Did The Edge beg to be allowed to put backing vocals on ‘Where The Streets Have No Name’ the night before the record was due to be delivered?

“It's even worse than that," he confesses. "We forgot to put the backing vocals on it. I don't know if he re-did them for a later pressing. I need to check that, but there were no backing vocals on ‘Streets’, although I think they did it for the video.”

What about the possibly apocryphal tale of Brian Eno having to be restrained from throwing ‘Streets’ in the bin?

“He and Brian had just lost the plot on that song. It's not their fault. Anyone would have lost the plot if they’d worked on it as much as they had. He's a lovely man. The great thing about Brian Eno is that he's so intelligent, but he will also talk to you about more earthy concerns [this isn’t quite what Steve said, but modesty must prevail] as well.”

Did your wife Kirsty MacColl decide the Joshua Tree track listing?

“Of course she did. Everyone else was completely fried," he recalls. "In tabloid speak, you've got a bubbly blonde, you've got a sultry brunette, and you've got a fiery redhead. Well, she was the epitome of a fiery redhead: she was very opinionated, and, God rest her soul, she was fantastic. She basically sat there and Edge sort of played her the beginnings of every song. She'd go, ‘Okay, that's good. That one? First. That one? I'll put that on side two. That one, that's a hit'. She’s the reason Joshua Tree is so front loaded.”

Warming to the topic, this good man continues.

“With The Joshua Tree, you’ve got side one, which is probably one of the greatest sides of music ever made. But until they went and played that album live a couple of years ago, side two, as a recording, was not as good. Side two of The Joshua Tree really came to life during those concerts. Much more than the recording, which was a little bit blurry, not as focused. But that's U2 in general; it takes them a long time to get it all together.”

Out Of Control

Lillywhite has mentioned in previous interviews that he suggested the band go out and road hone material first, before recording it.

“Well, of course," he says. "Especially from October. I'd go and see them play that album, which was a bit sleepy on the recording, and they really made it fiery. And it was like ‘Can't you just play the songs live first?’ In fact, later on in their career, they actually did that a little bit. But by that point, they were too big. And they became a bit self-conscious about it, and everyone was making bootlegs. There was a song called ‘Glastonbury’ [played several times on the U2360 tour and, allegedly, once recorded in Edge’s home studio with none other than Niall Bloody Stokes on backing vocals! This, or any other official recorded version, has yet to see the light of day], but they didn't quite get it all together, which is a pity.”

If I was to offer Lillywhite a trip in the Hot Press DeLorean, are there any recordings he’s made with the band that he would go back and change?

“The last thing I'm going to say to you, Pat Carty, is my theory of never listening to what you've done. When you're working on it, you can change it and that's good, but once you finished it, we don't really ever listen to our records. Not many artists do. There's only two emotions you can have if you listen back to it, either you like it, or you don't like it. If you like it, there is a possibility of complacency; if you don't like it, there's the possibility of uncertainty. Uncertainty and complacency are not good emotions. We try and just muddle our way through and carry on blind. Maybe we leave a little trail of seeds behind us, so we can so we can find our way out of the forest. Oh My GOD! Am I talking in riddles here?!?”

He might be starting to lose it, so I ask the final, horrible question: what’s his favourite U2 record?

“Well, as I say I haven't really listened to them. Funnily enough, ‘With Or Without You’ is played a lot in this household. I like the big songs. I like all of them. I have sat down and listened to October, occasionally, breaking my rule. Probably that album more than any other, because at the time, it was like, ‘Oh, that was a flop’, so I have it in my head that it's not good. But now when I listen to it, there's a certain tension, a certain sadness and an autumnal feel about October, that is very difficult to put on an album, because it comes from from a lot of sadness. Anyway, Pat…”

We'll stop it right there. As the man said, there's another anniversary coming up next year.

* * * * *

RELATED

- Opinion

- 16 Mar 23

Album Review: U2, Songs Of Surrender

- Opinion

- 03 Dec 21

The Songs That Saved Their Lives: U2 Achtung Baby 30

RELATED

- Opinion

- 18 Nov 20

All That They Can’t Leave Behind: U2 From Boy To Men

- Opinion

- 22 May 20

U2 - Covered

- Opinion

- 10 May 20

Happy Birthday U2 - Bono At 60

- Opinion

- 28 Apr 20

U2 - Under The Covers

- Opinion

- 22 Nov 19