- Opinion

- 07 Nov 22

A life takes years to live. In Bono’s case, it’s been 62 so far. So how do you pack all that you can’t leave behind into a mere 580 pages? The only option is to open your mouth – and your heart – and see what comes out. Surrender, it transpires, is a marvellously honest, open and finely tangled account of one man’s journey into the unknown. And how do you get to write about it when all around, mayhem rules? Well, that’s a different story...

Bono. Surrender. Come out with your hands up! I’d like to have had a week to write about it, and everything it entails. Instead, here we are, in the final throes of an issue of Hot Press that has pulled me in a hundred different directions so that I feel like a towel that got locked in the washing machine – and then, the way it happens, in a drier that’s stuck on repeat – and I am only starting. You could say it’s appropriate: like being dragged back to 1979 again, when I first sat down with the four boys in U2 for an interview and we stuck them on the cover of Hot Press.

That adventure in getting to know them just a little bit better involved a long day’s journey into night. There are times – so many back then! – when we haven’t a clue if we are doing the right thing or not. But that one seems to have turned out okay in the long run. Mind you, there are, I confess, moments when I doubt that I ever fully recovered from those early fortnightly battles getting Hot Press done. I am like an addict, still feeling the same burning need – or maybe, if I inflate my chest, it’s ambition – that every issue should be one that the collective bunkered down here can feel genuinely proud of. And I still go to the wire when it is necessary, which is more often than any sane individual could ever wish upon themselves.

So here we go again. The pages are being thrown in front of me as we speak. How might we fit these five into four? Is that headline alright? Did we ever find those pictures? Where should we look for the ones that are missing? Are we happy with the cover? I’m not sure if we’re going to fit that interview in! Do we run those two album reviews together or separately? These need to be chopped! That ad copy hasn’t come in. Did somebody mention lunch? What the fuck time is it and will we ever get finished this afternoon? What about this evening? Sometimes even I – especially I – don’t know the answer. But I pretend.

Everything’s gonna be alright. You have to believe that, don’t you? Say it slower. Everything is going to be alright. Even when it’s not true. Even when you get the news that someone in the wider family is dying. When it is only a matter of days or even hours till the sun finally goes down irretrievably on one more brave pagan soul. You travel to wherever it is you have to go, to say a last goodbye. Outside it is raining. Buckets of rain, buckets of tears. People talk quietly. Make it family only. No priests. Ashes to ashes. Dust to dust. We all hit an all-time low in the end.

Everything is going to be alright. You have to believe it, even when it’s not true. Even when you know it’s not true.

Advertisement

Like someone looking out the window now in Kyiv, Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv or Lviv. Waiting with their breaths held. For the next outrage. The next strike. The next drone, coming at you all the way from Iran, via the Kremlin. Hoping blindly that it will hit elsewhere. Not here. Not this house. Not this room. Not me or my children.

And if it does, the terrible thought that it would surely be best if it took us all. Not a thought you ever imagined would enter your head. I do not want to survive if you are taken away from me. Or you, my children, to be left alone to fend for yourselves. If it is going to happen, let it all happen at once. How has it come to this?

That is perhaps the biggest mystery of all. How can it be that we have descended so deep into the pit again? Across the world the alarm bells are ringing. The pendulum swings this way or that. But the arc these past ten years has been downwards.

Oh, mama, can this really be the end? Just for now, though, there is no time to contemplate that particular question. There are dykes that need fingers for putting in. The day grows short. Ti-i-i-ime is not on our side. A cold winter beckons us on.

Hopefully not into the abyss.

LEAVING HOME

Surrender begins with a gory scene. It is Bono at his best. “So here I am,” he says. “Mount Sinai Hospital. New York City.”

Advertisement

I am immediately impressed with his ability to make a sentence out of three words. No verb. Twice. The opening chapter of Surrender, Lights of Home, is thrillingly, powerfully written. It tells a story that people close to the U2 singer knew of. It had been advertised as something that couldn’t or wouldn’t be discussed, not till later anyway. There had been a brush with the grim reaper, but our man survived. This much we knew, but the details had been effectively kept under wraps. Even if it was just to preserve the scene, true crime style, so that it could be written about here first, any recalcitrance is proven more than justified.

The old rules still apply. Go in strong. Knock ‘em dead with the opening riff. A weak beginning and you’ve lost the crowd. Start with a single.

“I was born with an eccentric heart.”

You can tell straight away not just that Bono is a writer but that he is writer who knows what is doing. The narrative in the opening gambit flips back and forward in time. It moves between straightforward narrative and hallucinatory dream reveries. It is punchy here, reflective there. Visceral, visual and descriptive by turn. And it deals with the biggest question of all.

“Now this man is climbing up and onto my chest,” Bono writes, “wielding his blade with the combined forces of science and butchery. The forces required to break and enter someone’s heart. The magic that is medicine.”

It packs in both facts and feeling.

“I know it’s not going to feel like a good day,” the writer continues, “when I wake up after these eight hours of surgery, but I also know that waking up is better than the alternative.”

Advertisement

He not busy being re-born is busy dying.

Feeling and needing. Different things. But complementary.

“I’m so cold,” he complains, a few pars further on. “I need to be beside you. I need your warmth, I need your loveliness. I’m dressed for winter. I have big boots on in bed, but I’m freezing to death.”

In the opening section alone, there is pathos and poetry. There is his father Bob; and his lover Ali. There is music. There is self-revelation. There is bad language. “FUCK OFF,” Bob says. There is popular culture, the surgeon becoming confused with the crazed villain in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Three names for God. Psalm 32. Patti Smith. There is U2.

Bono with the love of his life, Ali Hewson (from the Hewson family archive)

“We are men who bear some scar tissue from our various struggles with the world,” he says of Larry, Edam, Edge and the other fella, “but whose eyes are remarkably clear considering the vicissitudes of playing stadiums for thirty-five years.”

Advertisement

This is him reflecting on the first night of the Innocence + Experience Tour in Vancouver, Canada.

“I have my fist in the air as I walk to the stage,” he recounts, “as I get ready to step inside the song. I will try over the next pages to explain what that means. But after forty years, I know if I can stay inside the songs, they will sing me and this night will be not work but play.”

And so we are off, stepping back in time to ’The Miracle (Of Joey Ramone)’. Bono is back in that moment when it all began. He is walking away from his house in Cedarwood Road. Heading to an early rehearsal with three other young North-side Dubliners.

“I am leaving home to find home,” he says. “And I am singing.”

A FUCKING GREAT BAND

That was a very good example of how it shouldn’t be done. It’s a friggin’ book you’re supposed to be writing about, you dingbat. Reviewing, is that the word they use? To think or talk about something again. Or to take another look. Well, there are 40 chapters in Surrender. That’s 606 words you’ve written on the first chapter alone. To devote the same space to each one we’d need 24,240 words in all. Amateur hour that!

Then again, the book is huge. Almost 600 pages, when you include the 24 glossy ones of pics from the Hewson family collection. It’s got Bono’s own handwriting, captions scrawled onto the snaps. Me, Iris, Bob, Norman, Butlin’s Mosney, Swimming pool, Co. Meath 1971. Bob is wearing shades and swimming trunks. Examine it at a certain angle and it is as if someone has transposed Bono’s head onto his father’s shoulders. Our genes are our destiny. But only up to a point. After that, obstacles notwithstanding, we are what we make of ourselves.

Advertisement

You don’t need to read Surrender to know that, but it helps. Because this is the story of someone who always wanted to be bigger – he jokes that this is true literally as well as metaphorically – better, doing more, reaching higher (and higher and higher).

So many imponderables. Near misses.

Often, as we know, with U2 that mission has meant reaching out to a higher power. We are told the story of the near-breakup of the band in 1981, when Edge’s Christian beliefs, and the desire to be part of the solution rather than the problem, seemed to get the better of him. “There are so many messy, complicated problems out there in the world,” Bono recalls Edge saying, “and maybe running away with the circus is not what we’re being called to.”

Larry, Bono, Edge and Adam. Photo by Colm Henry

Leaving the circus seemed like a good idea to Bono – or so he convinced himself, driving home in his Fiat 127.

“You tell yourself everything is ok because you’re doing the honourable thing,” he remembers, “and that such sacrifice is a measure of the seriousness of your commitment.”

Advertisement

And then he changes gear. “Maybe today we’d use the word indoctrinated,” he muses. “Perhaps that was the case, although none of us knew it.”

The plan to call it a day and get more involved in doing the Lord’s work is scuppered when the band’s manager Paul McGuinness – introduced to them by Bill Graham of Hot Press – argues that God couldn’t possibly want them to renege on contracts he has signed on their behalf to undertake a tour. In print, in the cold light of a completely different day, it doesn’t seem like such a strong argument. But there is self-deprecatory humour in the line Bono attributes to Adam that – as the band’s only non-Christian – he deserves an access-all-areas pass through the pearly gates just for the fact that he is in a band with Bono.

But it is Larry’s line that is most telling.

“I don’t want to be in a fucking Christian band,” Bono quotes him as saying. “I want to be in a fucking great band.”

Over the next 40 years or so they would have a good go at that. As we know. A very good go.

SOME KIND OF DYSFUNCTION

It’s a long story, and that’s only the start of it. There is great stuff in Surrender about what it is to be in a band. To be a songwriter. To be the frontman. The one who has to get up on stage every night on tour and open his mouth desperately hoping that the words will come out in the right order.

Advertisement

Sometimes artists make it look easy. That was never exactly U2’s way. They never minded being seen to be trying. The tours are disassembled here, and all of the anxieties and pressures are reflected. The big mistakes they made. And the rush of something else, something transcendent that uniquely comes from standing up in front of 60,000 people and letting fly.

Touring is tough. It takes it out of you. Things can and do go haywire. It was on tour that the band almost split up again. November 1993. U2 had released Zooropa, the follow-up to Achtung Baby, in July. But they were still on the Zoo TV tour, a fiercely original excursion, which had seen them adopt a whole new set of onstage strategies. This was the world of The Fly, MacPhisto and Mirror Ball Man. Of monster video screens, prank calls, flashing text messages and hanging Trabants. They had subjected themselves to a punishing schedule, taking in a total of 157 dates. Their Sydney gig was due to be shot for a Live Concert film. And then disaster struck.

“Having overshot the runway with drink and drugs, Adam ended up in the company of some party people whose job was to keep him at the party,” Bono recalls. It is the beginning of one of the most dramatic episodes in Surrender. You could argue that Adam is one of the real heroes of the book. He is a remarkably decent, kind, good man – which anyone who reads the book will appreciate. But this was the moment when he hit rock bottom. One of the great strengths of U2 as a thing is that the spirit of the three musketeers has found a new home. It is all for one and one for all. They stood by Adam and that faith was rewarded.

“I have come to see the band as a relay race,” Bono says, towards the end of what is a powerfully written chapter. “There are times when one member of the band seems to be striding forward faster than anyone else. Adam had it in the beginning, by far the more advanced. By Sydney he ran out of road, but he also started a new one.”

He describes it as Adam’s steep climb to recovery. “Adam surrendered to his higher power,” he says. And a little bit further on he muses: “It’s an extraordinary thing, the moment of surrender. To get down on your knees and to ask the silence to save you, to reveal itself to you.”

Frequently, Bono is hard on himself in Surrender.

“I had to ask questions of myself too,” he remembers of that moment at the end of the Zoo TV tour. “What was my drug of choice?

Advertisement

“This envelope pushing, where was that coming from? Was it some kind of dysfunction? That I don’t know when enough is enough? Was I singing to myself in a song like ‘Lemon’ from our 1993 record Zooropa?”

In the end, he concludes that the game is indeed worth the candle. The subtext says: as long as you don’t burn it at both ends.

SINCE WE WERE TEENAGERS

It is getting late. Darkness is falling outside. There is so much else that I could try to tell you about this book. That it isn’t perfect. That there are obvious gaps. That there are things that are missed. That there should be more on this, that or the other.

But this is someone else’s life. All 60-odd years of it. There is so much to be covered. Because it is about as far from an ordinary life as you could possibly imagine.

It is not just the story of a rock star. Or of a band battling its way across every rapid, all hands to the pump, and manifesting an almost unparalleled determination to stay in the moment, and remain – no, that’s not the right word – and be relevant.

Or of a songwriter, searching for the holy grail of words and music that somehow transcend the moment, that can live in the hearts and minds of audiences now and potentially forever into the future. Or of the collaborators – people like Steve Lillywhite, Brian Eno, Daniel Lanois, Flood and more – who help to chase the bones of songs and ideas into something that is ready, yes, to be put out there as the latest statement from a band that cares deeply about what it does, how it is seen and what impact it has – or might have – on the world of music, but also on the wider world of human interactions and affairs.

Advertisement

Bono, The Edge and Brian Eno at Slane by Colm Henry

Surrender offers unique and often enormously compelling insights into all of that music making and shaping. Into the art. Into the commerce behind the art. Into the contradictions and compromises. Into the whole goddam enchilada.

If that was all that had occupied Bono, then he would have had a packed life. But then there is the activism. The truly exceptional commitment he has shown to doing everything he can to make a difference to the lives of ordinary people across the enormous continent of Africa. The litany of leaders he has met, all the time thinking ahead and seeing who he might bring on board and how. There are great first-hand accounts of meetings and greetings with Bill Clinton, George Bush, Nelson Mandela, Barack Obama, George Soros, Steve Jobs, Warren Buffet, Mikhail Gorbachev, Vlodymyr Zelenskyy and dozens more in the higher echelons of politics and world affairs, in pursuit of another holy grail, that of debt relief.

Often in Surrender, Bono portrays himself as a pain in the arse. A guy who suffers from imposter syndrome. Who feels out of his depth. But he isn’t. He keeps pushing. Picking up the phone. Jumping on planes. Working. Talking to what some people at least will think of as the devil. He knows that there are occasions when you must sleep with the enemy. Notch by notch, he and the team in ONE and RED and DATA make ground.

All of this is fascinating stuff, and what Bono-bashers will most resent – but are unlikely to acknowledge – is that his grasp of all of the issues surrounding aid, trade and debt is finely tuned.

And then there are the celebrities, the friends and the people who are just passing through. In Surrender, you get a glimpse of a life that – by any standards – is enormously privileged. He knows this and acknowledges it. This is the gift that the fans of U2 have bestowed on him and on the band, and for the first time he opens the door into that world here, in a way that is frequently entertaining or – in the case of a tragedy like the deaths of Michael Hutchence and Paula Yates – heartfelt and moving.

Advertisement

He paints marvellously affectionate portraits of Edge, Adam, Larry and, with some grit added, Paul McGuinness. And of the other kids from Cedarwood Road he grew up with. Of Lypton Village. Of Gavin Friday and Guggi. But it is in relation to family that he is most emotionally revealing.

In Surrender, Bono – for the first time – lets the world in on the secret that his old sparring partner, his father Bob, had an affair with his wife Iris’s brother Jack Rankin’s wife, Barbara, and that they had a son. In a sense, this is a not-untypical story of modern Ireland, where a knock on the door can reveal a hidden past that no one had reckoned with, except perhaps in the hidden chambers of – or blisters on – their hearts. When his brother Norman – another strong presence in the book – called Bono to reveal the news, Bono already knew. He told Norman that Scott Rankin was their brother.

He wonders if this was something that he had figured out instinctively a long time ago. And that he had – unconsciously – held the apparent betrayal of Iris against Bob. And that this might explain not only the fractious relationship he always had with his father, but also the anger and anxiety and need to prove himself that have, at least to some extent, driven every aspect of his life.

It is big question and the best way of answering it is probably that this is human life. And that we are all flawed creatures.

Surrender is dedicated by Bono to his beloved Ali, whose calm presence is a marvellous constant throughout the book. In the penultimate chapter, Landlady, he is just back from the band’s most recent tour. He wakens up in bed in Temple Hill, in Killiney.

“I can hear Ali breathing,” he says, “and even with my ears dulled by the roar of the crowd and the noise that comes with putting up and pulling down a rock ’n’ roll show, this is better than silence...

“The noise of the tour and its kinetic energy now replaced by the soft crashing of the waves and the murmurings of the woman I have loved since we were teenagers.”

Advertisement

Now, there’s a statement. Surrender is a life story brilliantly told.

It is by a fella called Bono, of whom you’ve probably heard.

The end.

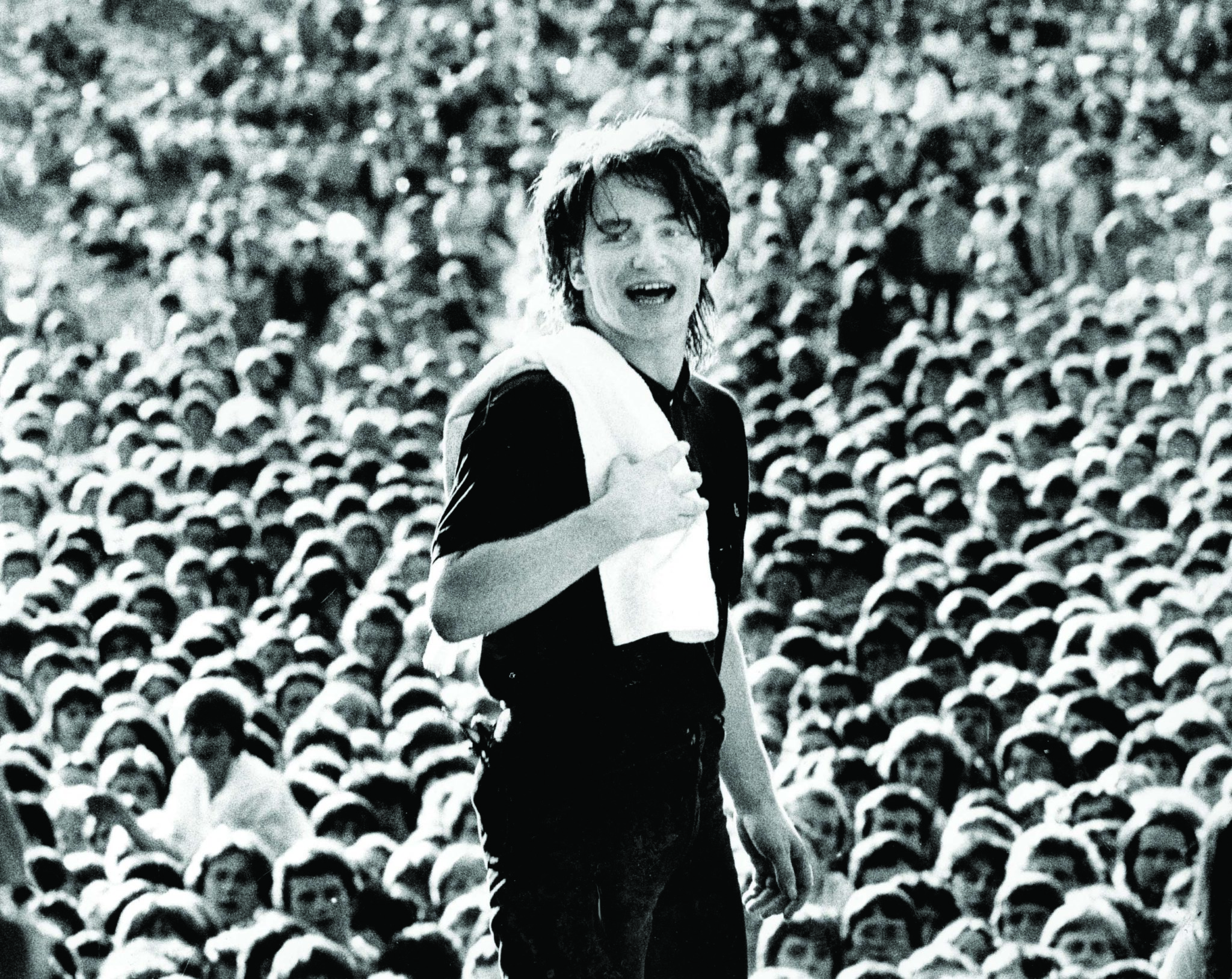

Bono live at Slane, 1981. Photo by Colm Henry

The new issue of Hot Press – featuring cover star Bono – is out now. Inside this special issue, you’ll find a mischievously funny and revealing Q&A with Bono, an exclusive extract from Surrender, and the handwritten text of a Bono-penned article for Hot Press, also dating back to 1980.