- Music

- 05 Jan 24

Thurston Moore: "I can see that Cork gig so remarkably clearly in my mind"

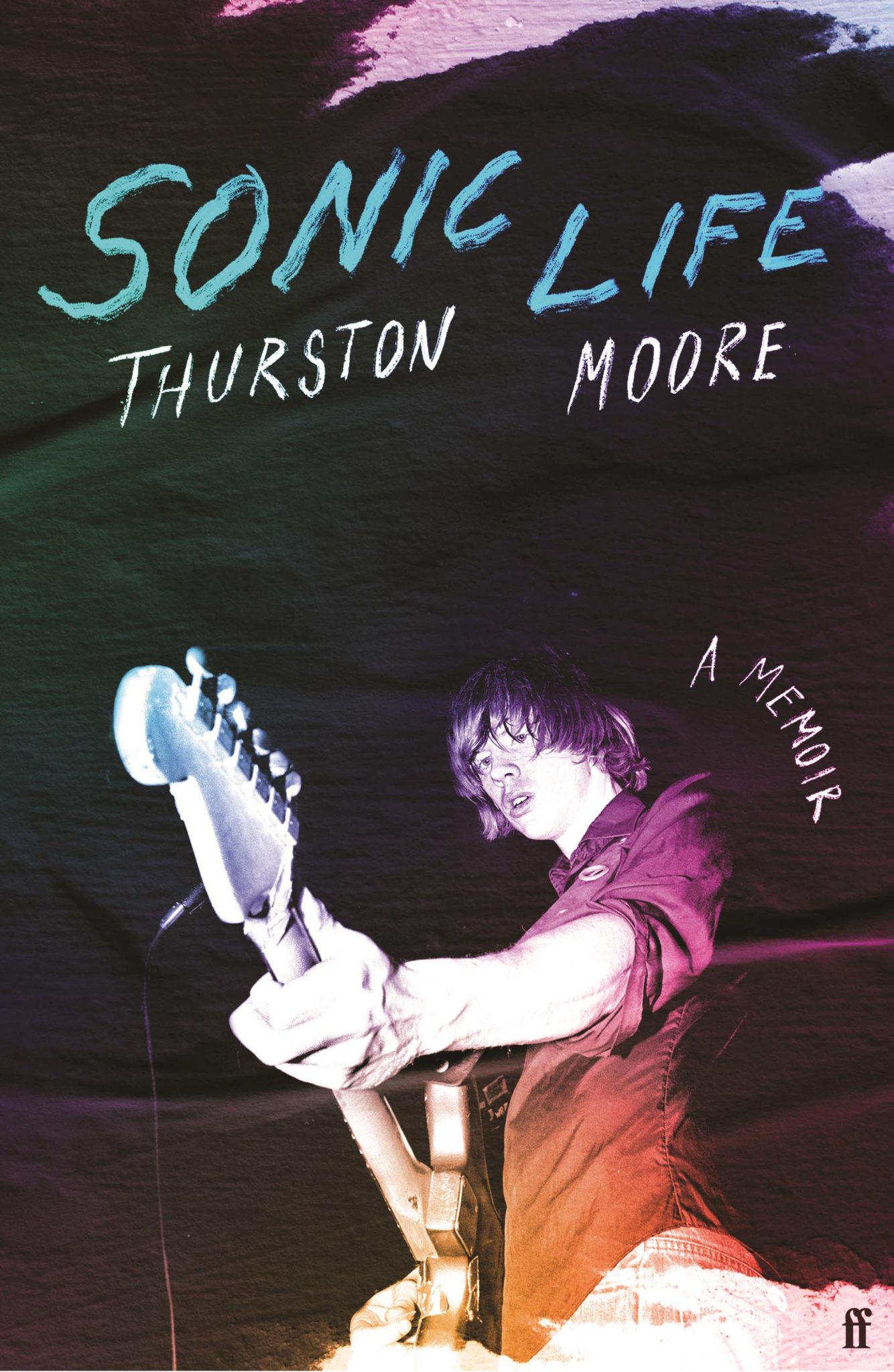

Having recently published his instant classic memoir Sonic Life, legendary guitarist Thurston Moore discusses no-wave, Irish punk, star-studded Hollywood parties, Nirvana in Cork, and playing Bowie’s 50th birthday bash.

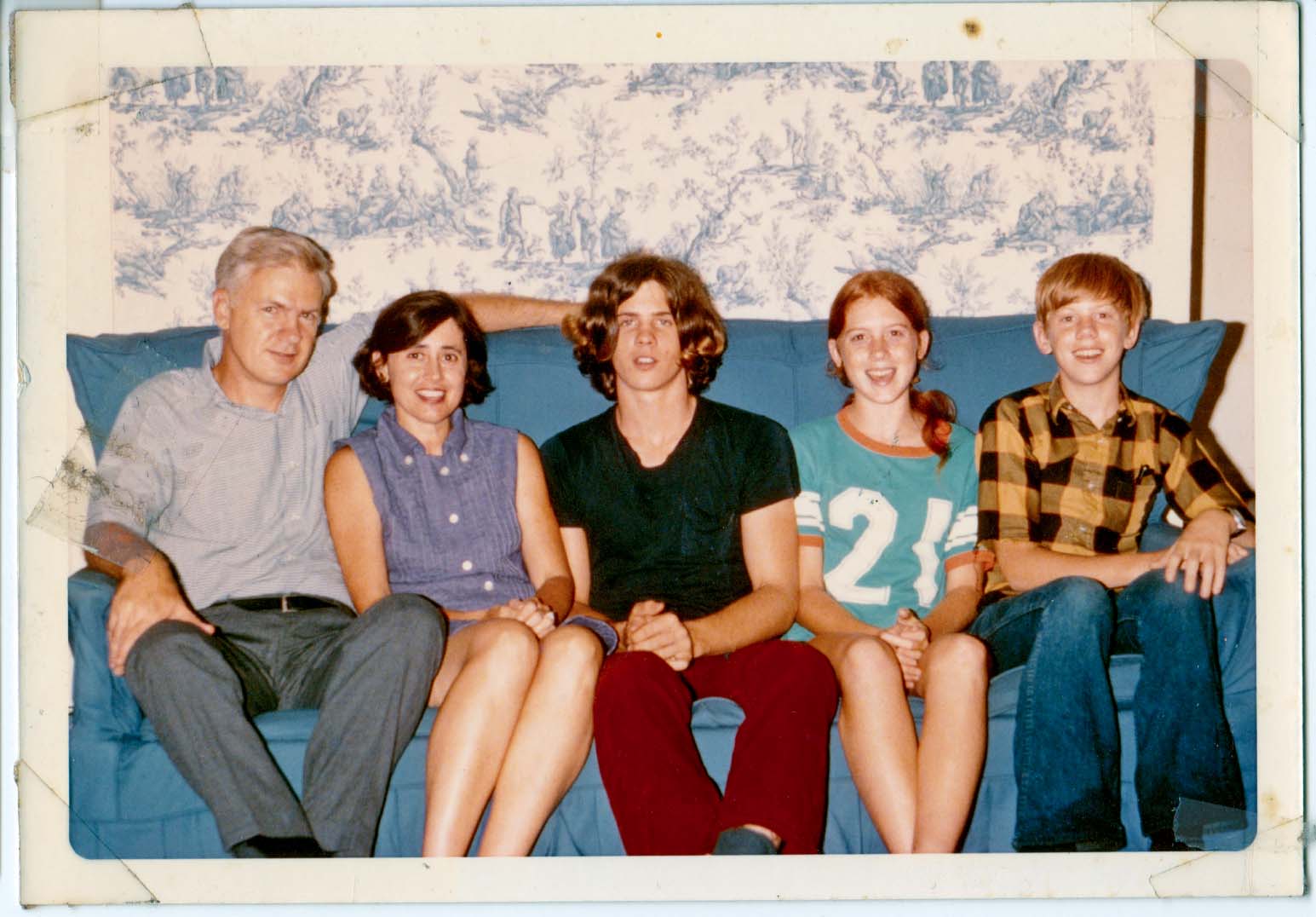

As a connoisseur of rock bios, I don’t take it lightly when I say Thurston Moore’s memoir Sonic Life is one of the best music books I’ve ever read. Now 65, the celebrated guitarist reflects on a remarkable life that started with a middle-class upbringing in rural Connecticut, before he moved to New York and formed legendary alternative noiseniks Sonic Youth. The tale is by turns insightful, wildly entertaining, occasionally hilarious and ultimately quite moving.

Also comprised of Moore’s life partner Kim Gordon, guitarist Lee Ranaldo and drummer Steve Shelley, Sonic Youth would eventually become doyens of alternative culture in the ‘90s via cult classic albums like Bad Moon Rising, Daydream Nation, Goo and Dirty.

Mentors of Nirvana, beloved of everyone from David Bowie to Radiohead, Sonic Youth in that decade defined a certain brand of New York cool in the way bands like The Velvet Underground, The Ramones, Blondie and Talking Heads had for a previous generation.

With the golden couple of Moore and Gordon at the helm, the band inhabited a New York that seemed almost like a grungier version of the Gilded Age, populated by friends and collaborators like Harmony Korine, Chloe Sevigny, Spike Jonze, Sofia Coppola, the Beastie Boys and Public Enemy.

Life being life, of course, there would eventually be a flipside to the roaring ‘90s in NYC. Like a no-wave version of a Flaubert novel, the Moore and Gordon union eventually unravelled in 2011, bringing an abrupt end to Sonic Youth. Previously, Gordon had outlined the whole painful episode in her own memoir, 2015’s superb Girl In A Band. These days based in London, Moore has been dealing with other issues of late.

In the month after our interview, the guitarist cancelled the US tour for Sonic Life, and revealed to The New York Times that he has been living with a heart condition for several years. “But this year, it became slightly concerning,” he told the paper. “I was finding myself at times to be so weak I could hardly walk around the neighbourhood.”

Although urged by his doctor not to fly, thankfully Moore noted that the “prognosis is very good”, and he was able to complete scheduled events in the UK. Having interviewed Moore several times before, it was a pleasure to catch up with the characteristically affable musician over Zoom, and hear his erudite and often humorous take on the Sonic Youth story.

Filled with socio-political tumult even as it midwifed punk, hip-hop and disco, the ‘70s New York Moore portrays at the outset of Sonic Life has only become more mythologised in pop culture as time has gone on. In recent times, the blockbuster Joker and John Wick spin-off series The Continental are but two examples to use the New York of that period as a backdrop.

Moore was among the artists to have experienced the moment in real time, as was Martin Scorsese, who famously captured the dark underbelly of ‘70s NYC in his masterpiece Taxi Driver.

“It’s funny you mention that movie, because I remember when it was first released in ‘75 or ‘76,” reflects Moore. “I saw it with my friend Harold, who figures quite prominently early in the book - we pal around and discover things together as teenagers. I remember going to see Taxi Driver and thinking so much about how New York City was so alluring, even in the decayed state of chaos that film shows.

“But Scorsese always had this underlying spiritual nature about life in the big city, and these conflicts of morality and how to survive them - or not. I was really drawn to that. Just that narration by the De Niro protagonist about the rain washing away the scum of the city, it had this very religious connotation. It struck me in my youth, and drew me towards wanting to be in that environment, as opposed to the safe, rural family world I was in.

“For some reason, it drew me towards wanting to be in this subversive place, and I don’t know why. One of the reasons I wrote the book is I wanted to investigate why anyone who’s in a zone of comfort - a middle class white kid in rural Connecticut - would want to go into New York City. For me, there was a creative world there; it was somewhere I could express the creative impulse I was feeling. So a movie like Taxi Driver was really significant.”

It seemed like the darker aspects of the city found their expression in the nihilism of no-wave, which had Sonic Youth at the forefront, and which would also be documented in the Brian Eno-curated anthology, No New York.

”Oh, for sure,” nods Thurston. “I had an older brother and it was a musical household. We were listening to the typical stuff: Beatles, Jefferson Airplane, Creem, Rolling Stones. But I think I mention in the book - and it’s not even a conceit I came up with - that in ‘75 and ‘76, there was this idea of not escaping to the country. Not going to Woodstock, and meeting the expectations of society to be straight, and support the US in Vietnam and all this.”

The antidote would eventually emerge with the New York punk scene kickstarted by the New York Dolls, fronted by the brilliantly charismatic David Johansen, recently the subject of the Scorsese documentary Personality Crisis.

”You had this idea of the New York Dolls actually enjoying life in the city,” Thurston continues. “The city had never been cool. The Stooges or The MC5 being Detroit bands and very urban, that wasn’t considered hip. I think it was just considered an aberration in youth culture in the late ‘60s - these people would not leave the city and they were really antagonistic. They were holding guns in the air and saying, ‘We’re gonna fight in the streets.’ Those bands then became models for The Ramones.”

KEY MOMENT

In pinpointing a key moment in the development of Sonic Youth, Moore highlights downtown arts venue The Kitchen.

“It was really interesting, because it was an experimental music and video laboratory,” he recalls. “Rock music was brought into it with the clientele kicking and screaming! But that really changed everything and that’s where we come in around ‘78/’79. Rhys Chatham is probably the most important person in that scene, in allowing it to happen.

“And then he himself was radicalised by seeing The Ramones as this great moment of minimalism. He’s coming out of the minimalist music of Philip Glass and Steve Reich - not people The Ramones were talking about! The Ramones are one of the most curious musical constructs in the history of rock and roll. They weren’t intellectuals, they were these kids who came across this idea that was actually incredibly high concept.

“We’ll dress the same, we’ll take the same last name - on one level it was really cute, and on another, it was astoundingly effective.”

On a personal level, I was delighted to see Hot Press get a mention in Sonic Life, with one-time HP contributor David Donohoe producing a South Bank Show special on the no-wave scene.

”When David presented it, it seemed like a great idea,” says Thurston. “We were at the age where any kind of attention like that made sense. For me, Ireland was its own world of excitement and energy. It was significantly separate from what was going on in England. I figured that out when I first saw the documentary Shellshock Rock. The filmmaker of Shellshock Rock had brought those reels to New York City when he made it and showed it at Club 57.

“I saw a flyer and went to see it. I remember being completely engaged in that film at the time, and then for years, I would mention to people, ‘Have you ever heard of this film about the Irish punk scene?’ Nobody knew about it. I mean, it was literally about 20 years later that you’d finally read about it, when Mojo was starting. Now everybody knows about it, cos I think it got a DVD release, but it always stuck with me.

”It informed me a lot about the sensibility that was so loyal to itself, and a community that felt already divorced from the democratic world out there. It certainly had its own internalised struggles and celebrations, and the music itself was incredible. Then you had characters like Terri Hooley, where it was just like, ‘Wow.’ There was one scene where he was like, ‘Ireland has the vision’, and these kids were jumping around holding his shoulders. It was incredible.”

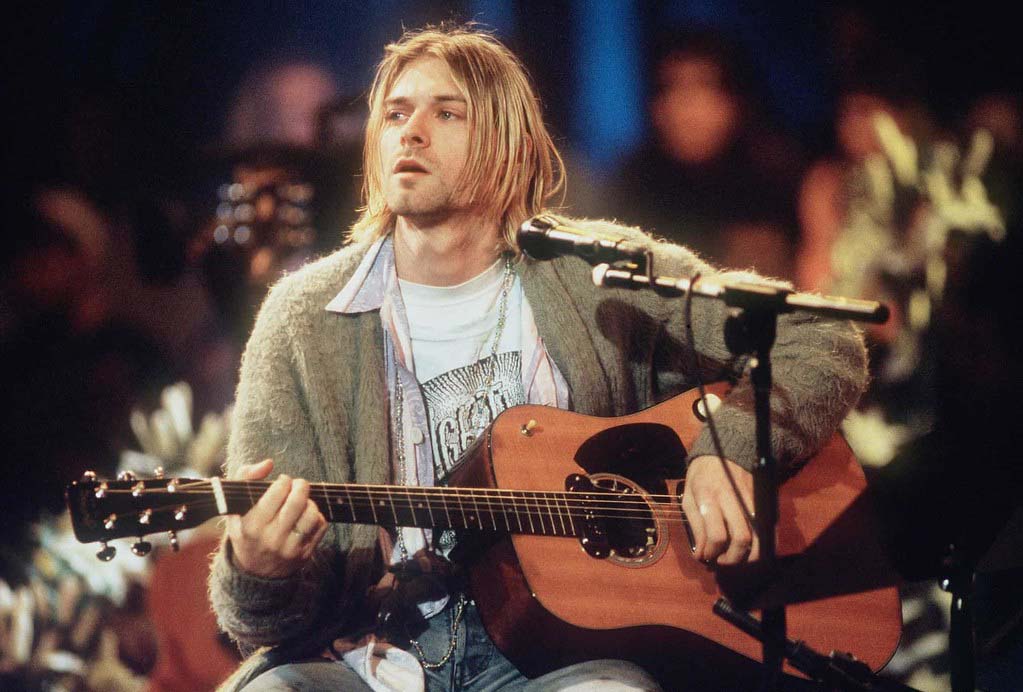

One of the roles Sonic Youth most became famous for was giving up a leg-up to a nascent Nirvana. The Seattle band followed Sonic Youth’s lead in signing for the major label Geffen, and Thurston and co. would also take Nirvana out on tour in the build-up to Nevermind in 1991. That tour kicked off with what are now probably two of the most famous Irish rock gigs ever, at Sir Henry’s in Cork and the Top Hat in Dun Laoghaire.

It marked the first time Sonic Youth met Nirvana’s new drummer, Dave Grohl, just days after Kurt and co. had shot the video for ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ in Los Angeles. With this year being the 30th anniversary of Nirvana’s darkly magisterial masterpiece In Utero, I recently revisited the ‘Heart Shaped Box’ video. Though directed by Anton Corbijn, the clip’s warped fairytale vibe was all Cobain’s concept - yet another example of his remarkable all-round artistic flair.

“He was an artist,” says Thurston. “We did a record that was only available in Australia and we used some of Kurt’s art on the front. He also did a drawing on the back, of Courtney Love and Kat Bjelland arguing with guns. But the picture on the front was a baby doll sitting in the corner. I remember asking him about using that work, and we shared management.

”At the time it was Danny Goldberg, and John Silva - who facilities everything to this day - was working with him. I remember Danny saying, ‘It’s really good you’re using that, because in some ways, I think Kurt would really like to be seen as more than just some guy with a guitar playing songs. He goes home and writes and does paintings.’ He was expressing himself in different ways.

”The idea of fame and celebrity when you’re barely out of your twenties, it’s sort of in conflict with the stability of what you should have in a life like that. Of course, that became really manifest for him, because he had his own issues with addiction etc. It ultimately killed him. But when I think of him, I think of him as more than who people know, as the guy who wrote ‘Teen Spirit’.”

NIRVANA IN CORK

As Moore elaborates, Cobain’s visual talents brought another dimension to Nirvana.

”The guy who you see making a video like ‘Heart Shaped Box’, there’s a lot going on there,” he continues. “It’s not like he was some overly intellectual punk rock kid. He had a great vision, but he wasn’t the only one. There’s a lot of people who got into that scene because they had visionary impulses. He was able to transcend that by the quality of his transmission, which was basically his voice and his physicality.

”The way he sang, I knew right away that his voice - that sandstorm - would turn them into something more than Jesus Lizard or Mudhoney or whatever. There’s something inside transcending this model that’s very normal: it’s straight ahead punk rock in a way. But there’s a je ne sais quoi that you can’t replicate. Or you can replicate it, but it will never be exactly that.”

Moore, meanwhile, has vivid memories of Sonic Youth and Nirvana’s Irish dates.

”In the book, I talk about that first Irish show I played with them in Cork,” he says. “That’s become this legendary show, but I can see that gig so remarkably clearly in my mind. I always remember when they first went onstage, and Kurt sang a song acapella, and then Dave came in. But I remember standing there thinking, ‘Nobody in the audience knows who this band is.’

“Maybe there were one or two kids who were hip enough to have the first record, but I don’t think so – they’re waiting for us. But Nirvana come out and within two minutes, everybody is there; it’s over. Everybody is like, ‘This is as good as it gets, this is what we want in our lives. Here it is: it’s being delivered to us and it’s happening right on this stage.’ I was standing there thinking, ‘This is everything that we can offer.’”

Ultimately, Sonic Youth’s ‘90s adventures would see them mix in the rarefied world of superstar celebrity. Staying in LA to attend the MTV Movie Awards, as part of the supergroup for the Beatles-themed film Backbeat - which also included Grohl - Moore inadvertently ended up hosting a party in his hotel room that was akin to a Gen X last supper.

With attendees including Quentin Tarantino, Winona Ryder and Billy Corgan, back in New York, a sheepish Moore was contacted by his management to inform him that the hotel bill had run to $40,000.

”It was the very first MTV Movie Awards, they were breaking out of being a music monolith,” says Thurston. “They were getting into movies and it was like, ‘Oh god, MTV is ruling the universe.’ And then we were in this bacchanalia! We were recording the Backbeat soundtrack then, and I always remember, it was at a point where we were being completely and utterly catered to.

”It was something that was unusual for us - it was even unusual for Dave Grohl. Because everything had happened so quickly in his world, and then Kurt dies, and he’s sort of like, ‘What now?’ Then we were doing this project, and I always remember they said, the movie company will rent a car for each of you so you can get to the studio. I said, ‘Okay, we want four convertible Mustangs’. It was kind of a joke - and that’s what we got! They were there in the studio parking lot.

”I always remember Grohl saying, ‘Did you ask for four convertible Mustangs?!’ I went, ‘Yeah, why - did we get them?’ It was like, ‘We can do whatever we want!’ Even to this day, I realised there are bands who have that in their world, and they’re really young. They snap their fingers and they have this thing. I certainly don’t have that in my world anymore, and I probably only had it for a second right around then, but I knew that it was really dangerous. It was like, ‘I don’t ever want to be there actually, to tell you the truth’.”

BOWIE’S 50th BIRTHDAY

Finally, I come to Sonic Youth’s appearance at David Bowie’s 50th birthday bash at Madison Square Garden in 1997. As part of a bill of alt-rock Galacticos that included Lou Reed, Robert Smith, Frank Black and the ubiquitous Grohl and Corgan, Sonic Youth’s slot saw them prevailed upon to deliver an apocalyptic take on the Bowie deep cut ‘I’m Afraid Of Americans’.

”That’s what he wanted us to do,” says Thurston. “It was sort of obvious from the start. I remember going to the studio to hear the song and he welcomed us there. I immediately got it with him, because it was like, ‘Oh, he knows how to make everybody feel comfortable in a room, while being the most imperious person in a room, without trying.’ He was smiling and welcoming, but it was, ‘I’m in charge here.’

”At the same time, he was explaining his new music on Earthling and saying how, since he had found jungle music, it was a completely open palette for him to be everything he wanted. I remember sitting there going, ‘What the fuck are you going on about - jungle music?!’ (laughs). No offence to jungle, it has its merits and I get it, it’s cool, but that is not the be-all and end-all of who David Bowie was.”

Still, the Dame’s love of the new form was infectious.

”There was something really sweet about the fact he was so enthused about this new genre,” continues Thurston. “He’s always been somebody who would take genre and recalibrate it to his own vision. Jagger does the same thing in the context of The Rolling Stones. It was like, ‘We can either play Muddy Waters riffs forever, or we can play some disco.’ Keith can roll his eyes all he wants in his book, but Jagger knows how to transcend their own music with his voice and Keith’s playing.

”So there’s a certain brilliance to that. In a lot of ways, I think Bowie really studied Jagger growing up. Jagger’s really important in that respect, because he’s so smart. But I remember sitting there thinking, ‘You’re not gonna sell me on this.’ It was like, ‘We’ll play it, and I know what you want us to do.”

But at the same time, when we did play onstage at that concert, I remember thinking, ‘There’s no way we can actually do what you want us to do - be these Americans destroying this song - because you’re band has so much firepower right now with their amplification and we do not.

”There’s a limitation to what we’re doing, so we’re almost here theatrically in a way.’ So I remember thinking, Oh, we were somewhat defanged.’”

Having listened to that performance umpteen times over the years, I’m going to disagree with Thurston here - I think his guitar playing during the song is like a nuclear detonation.

“That’s good!” he beams. “The fuzz-boxes were cranked as much as possible, because I knew we had to get over. Reeves Gabrels was effortlessly dominating the soundscape! It was cool and a fantastic experience, but I remember thinking, ‘Wow, 50 years old - what are you going to do now?!’ Looking back as a 65-year-old I’m like, ‘Wait a second – what do you do now?!’”

- Sonic Life is out now.

RELATED

- Music

- 12 Feb 25

Backstreet Boys announce Las Vegas Sphere residency

- Film And TV

- 09 Sep 24