- Music

- 27 Jul 18

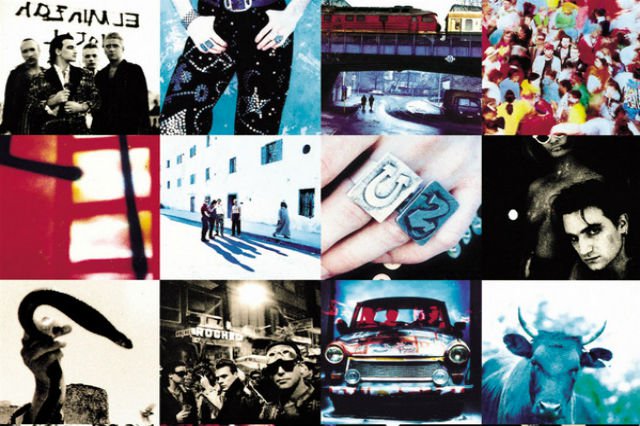

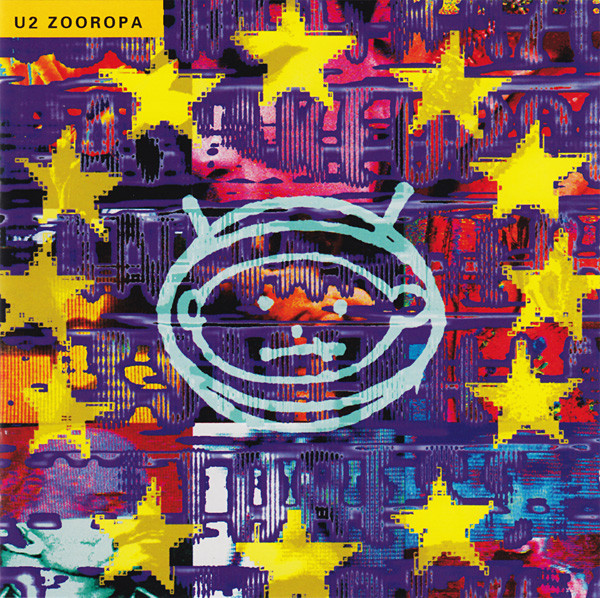

U2's Achtung Baby, Zooropa & The Best Of 1980-1990 Remastered on Vinyl

U2's two most famous '90s albums, and their definitive 1980-1990 greatest hits album, have been remastered and pressed on 180gsm double LP black vinyl. Relive the original Hot Press reviews here.

'Even better than the real thing…'

Released tomorrow, July 27, Achtung Baby (1991), Zooropa (1993) and The Best of 1980-1990 (1998), remastered and pressed on 180gsm double LP black vinyl - https://t.co/KB4EGM8OaH#realthing #achtungbaby #zooropa #vinyl pic.twitter.com/06XDJzjCsx— U2 (@U2) July 26, 2018

Achtung Baby U2 Niall Stokes [originally published in 1991]

There is no question about it. He may look as if he's been dipped in a bottle of red ink, but it is Adam who stands there bollock naked before the camera and the world on the back sleeve of the latest, long playing opus from the band whose name begins with U and ends with 2. And is that Eve who hovers topless behind Bono on the front?

It's a long way from the palpable innocence of Boy, this seething odyssey into the dark underbelly of inter-personal exchange, signalled on the cover by a series of images of shameless lust for low-life and the exotic. It's a long way too from the clarion-like conviction of those early years, best characterised in the religious dedication of 'Gloria'. “I try to speak up”, Bono sang back then, if you remember, “but only in you am I complete. Gloria in eo Domino.” And the guitars rang and the angels sang and the heavens rejoiced. Rejoice! I cannot think of a more alien concept to Achtung Baby.

Instead we are confronted here with a world of intense uncertainty, a world in which bearings have been lost, in which cruelty and betrayal, lust and infidelity walk hand in hand – a world in which the metaphors of religion have quite clearly given way to the metaphors of sex. “If you want to kiss the sky, Better learn how to kneel,” Bono sings on 'Mysterious Ways', and in another context it might have been taken as a reference to prayer. But here humility gives way to humiliation, as he interjects with the authority of a dominatrix: “On your knees, boy”.

Pleasure and pain. The desire to deny those to whom we are closest the freedom we crave for ourselves. Confronting the terrible truth that in love there are no rules – these are the kind of themes that refuse to be ignored when all your own assumptions of certainty and security and fidelity are blown apart on an intensely personal level.

Achtung Baby is not U2's Blood On The Tracks but at the very least it is a distant cousin of that epic saga, full of pain, hurt and resentment.

It opens on an appropriately disorientating note. Like a machine it splutters into life with ugly slabs of industrial noise. Larry picks up a harsh techno beat and Bono's dehumanised voice comes in over the top, offering itself up to chance. “(I'm) ready for the shuffle, ready for the deal, ready to let go of the steering wheel, I'm ready, ready for the crush!” There is an undercurrent of impending violence here, a thread of anxiety that runs throughout 'Zoo Station'. But there is also a sense of fearlessness that comes from recognising the animal in all of us. “In the cool of the night, in the warmth of the breeze,” Bono sings. “I'll be crawling around on hands and knees.” But he's ready to say that he's glad to be alive all the same. Voices reassure us that “It's alright, it's alright, it's alright” – but they sound more like riot police trying to control a demonstration which has exploded in panic than anyone genuinely capable of pouring calming oil on troubled waters.

Achtung Baby is loaded with these kinds of paradoxes. In many ways it is the bleakest U2 album, but it also contains some of their most obvious singles – pop songs which are deceptively accessible while dealing in harrowing emotions, the illusion of something throwaway masking the search for a deeper truth. Achtung Baby at once evokes the spirit of T. Rex and Scott Walker, The Beatles and the Stones, Bob Marley, Al Green and Leonard Cohen. It is trashy, ambitious, subversive and profound. It sounds less like the U2 that we know than anything they have done before and yet it is unmistakably them, their signature indelibly inscribed into the grooves, from the Edge's first guitar colourings on the opening track onwards.

It can seem gratuitous, after a brief acquaintance with a record, to identify highlights because as every critic knows, where music is concerned, colour and shading and emphasis shift with time and sometimes it's only after months that particular songs insinuate themselves into fullness. But there are cuts here whose potency defies equivocation. On first hearing, and still one week later, 'One' seems transcendant, a magnificent synthesis of elements: words and music, rhythm, instrumentation, arrangement and intonation combine to create something that speaks a language beyond logic, the definitive language of emotional truth. “Well it's too late tonight,” Bono sings, “to drag the past out into the light…” and anyone who doesn't understand, well, they haven't been there.

Whoever chose the organ here was a genius – or maybe, as is so often the case in recording, it simply fell into place. The melody evokes the ghost of Led Zeppelin at their finest. The mocking vocal undercurrents are brilliantly reminiscent of The Rolling Stones circa Sympathy For The Devil. Are these things accident or design? And who chose to add a touch of strings where sax would have been the obvious choice?

'One' looks back to Bob Marley, it recalls the euphoria of 'Angel Of Harlem' from Rattle And Hum and on the final magnificent 4-chord trick of the outro, Al Green looms large behind Bono's vocal performance. Among all these elements it's impossible to say what makes this so utterly inspirational, but it is just that, soul music that avoids the obvious clichés of the genre and cuts to the core. It would, it seems to me, be a certain No. 1 hit – as if that accolade should mean anything! But of course it does, when you imagine the dark brooding mystery of this song being resolved over and over again on mainstream radio.

But then Achtung Baby is full of both potential hits – and dark, brooding mystery. 'Even Better Than The Real Thing' is pure pop, The Beatles of Revolver, and Marc Bolan joined together to culminate in a soulful plea à la Sly Stone. Except that here the appeal to “take me higher” feels utterly and explicitly sexual, rather than spiritual in its intent.

The use of voices is crucial throughout Achtung Baby. Nothing is ever as it seems to be – and where you think that it might, here they come, the voices, buried in the mix, rising and falling, a running ironic commentary on the main theme. 'Until The End Of The World' offers a doomy narrative of decadence and indulgence, reminiscent of Leonard Cohen, which takes on a psychedelic surrealism in the instrumental section before bowing out on pounding drums and a mounting babel of voices, like some medieval vision of the Apocalypse, transported into a rock'n'roll context.

There are times when the record seems to have been recorded underwater, in a black tunnel, or through a long (long) dark night of the soul. The bass on 'So Cruel' is sub-aquaesque like a baby's heartbeat on a foetal monitor. "I gave you everything you wanted", Bono declares. "It wasn't what you wanted". And in the background the voices moan, a kind of mock chorus incapable of taking the personal tragedy in the song too seriously.

A ghost, whose presence is palpable through all of this, weaves in and out of focus – the woman who moves in 'Mysterious Ways'. There is an impression at times of a conversation between band members, or that the theme involves all women, or indeed all the subjects (or the objects) of our love, male or female. And the conclusion is that even love itself, shrouded as it can be in rhetoric, equivocation, pose and dishonesty, is not to be trusted.

It would be wrong to take any or all of this as autobiographical – there is certainly more of the Edge in the lyrics than on previous U2 albums, and doubtless Bono is acknowledging dark elements – or elements that might conventionally be seen as dark – in his own psyche. But there are personae adrift across the landscape of Achtung Baby also.

To what extent is the lead singer in a band an actor, donning masks, adopting stances and expressing emotions which are only partially his own? Or to frame the question differently, are we the audience not also actors, pretending to be something which we are not but which gives us the illusion of a place in this world? There is a sense here of a band not so much on the run as on the slide, their grip loosened if not lost, opening themselves up to the teeming risks of life on the edge – and revelling in that new definition of freedom.

It’s a tightrope act, acknowledging that everything we feel and do is conditional, in which there is always, always, always the possibility of disaster, of being exposed, of being uncovered as a fraud and a whore. “I must be an acrobat to talk like this and act like that”, Bono acknowledges in 'Acrobat' a song which for some reason sounds to me like a message to Sinéad O'Connor with its final plea – “don't let the bastards grind you down.”

But in the end Achtung Baby is so magnificently contrary that if effectively redefines freedom on its own terms. The thread may be ripping, as Bono attests in the final Scott Walker-esque ballad 'Love Is Blindness', the knot, indeed, may be slipping, but those strange illogical reassurances with which the album is littered do indeed finally make sense.

Achtung Baby plunges into the rich complexity of adult experience, the spiritual, the cerebral and the sensual all clashing in a cauldron of ambition, insecurity and desire. Ostensibly decadent, sensual and dark, it betrays a seam of optimism reborn out of personal, social and political chaos. It is a record of, and for, these times.

Achtung! It's dangerous because it's honest. Or maybe, being honest, it truly isn't dangerous at all…

Zooropa U2 Bill Graham [originally published in 1993]

Usually, the road makes you (and U2) more manic. Since “Rattle and Hum” was their most frantic, scattershot album, you might expect “Zooropa” also to be tinged by all the volatile experiences of touring. If so, it’s expertly hidden. Without its own “Helterskelter”, U2’s latest is no roller-coaster. The major surprise is that it’s a far more measured, coherent record than “Achtung Baby”.

“Zoo T.V.” may have been dramatised as a circus of media overload and misinformation, but “Zooropa” dives beneath all that surface chaos and static. Instead it distils the music and makes the decisions that were delayed at the several crossroads of “Achtung Baby”.

That album occasionally suffered from an air of contrivance, as if they felt under pressure to prove themselves. But once your ears have unlocked the codes of “Zooropa”, you’ll find it wins by its consistency of tone and scale. Nothing here screams ‘hit’ like “One”, but neither are their tracks when you wonder if U2 are second-guessing either their audience or radio programmers.

The key shift occurs in The Edge’s role. Credited as co-producer, he’s less a guitar hitman than their sound effects handyman. If not totally dismissed, the glam/noise/R’n’B tumult of “Achung Baby” has been sent to the back of the class. And if you want a convenient access route to “Zooropa”, it can sometimes sound like the progeny of the lush, undulating atmospherics of “The Unforgettable Fire”, crossed with Bowie’s “Low” albeit – and very much albeit – proceedings from the sadly undervalued contribution of the Alomar/Davis/Murray rhythm team to that project.

“Zooropa” also flags U2 at their most purely musical. Really Bono’s lyrics can’t be pinned down. European foreign and agricultural ministers can sleep easy; if Bono’s got any views on the CAP and on the Bosnian crisis, he’s keeping them for his table talk. Instead he’s transformed himself into a set of ciphers, a strangely hazy and often mystified quest, a road movie at 30,000 feet above the arteries of Europe, a series of dreams in a twilight zone where you’re never entirely certain if U2 are playing at sunset or just before the dawn.

Long ago U2 used to somewhat shamefacedly accept they were the gang who couldn’t dance straight. And yet far more than “Achung Baby”, this record opens up new vistas for white European dance rock. Again U2 are masters of disguise since there’s no riff that sends me dashing to the Seventies section of my record collection, inwardly muttering my suspicions of crass larceny.

As with “Achung Baby”, Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen step forward as the indispensable facilitators of the other two’s imaginations. Check out how they pare “Babyface” down to the bare essentials. Or how Adam lubricates “Some Days Are Better Than Others”. Now U2 put up their own funk; they don’t need to pilfer any mouldy leavings from the vaults.

Gaining their own good groove, U2 have also ceased to heckle. The first single, “Numb”, casting Edge as a Kraftwerk replicant, is poker-faced cheek, a track that proves the fundamental but usually forgotten fact that Rap is anything you can get away with, so long as you get the rhythms tied to the floor.

It also shows how U2 now cast themselves as the Rorshach not the Dalton Brothers. Sometime in the future, “Numb” may evolve into Edge’s comic “Louie Louie” turn but here it’s his counter part to Bono’s own role-playing. “Stay (Faraway, So close)” places itself at a crux of paralysis and disorientation – “up with the static and the radio” – where “with satellite television, you can go anywhere/Miami, New Orleans, London, Belfast and Berlin”. Even in heaven, you can hear the holograms howl and Bono, as either (or both) star or lover, can only describe the distance where “if you listen, I can’t call…if you shout, I’ll only hear you”.

Too evasive? Does this self-proclaimed action painter want to have it every way? Possibly on the most literal levels of meaning but after “Zoo T.V.” you also have to envisage Bono’s lyrics as skeleton scripts to be fleshed out later on stage, themes for future theatric(k)s. These songs are so depictive. On a superficial reading, “Babyface” could be the record’s warmest, most affectionate track, a song to suit any love match between any couple of kooks- unless you’ve been previously alerted by Bono’s interview with Joe Jackson, where he’s instead insisting the song’s about the seamier juvenilia of satellite porn.

But move over Silvio Beriesconi and tell Rupert Murdoch the news! At its best, “Zooropa” is Sky-funk, music from a band who, permanently or temporarily, have renounced the old folkways for the new airways to declare that white men, they speak with digital tongue. So “Lemon”, the most graceful cut, stretches casually off into the firmament, due witness that U2’s music is most intoxicating when its rhymes soar with awe.

Then there’s the patchwork quilt of the opening title track. Almost a trilogy, it uncoils from a lengthy Gothic intro of Edge and Eno treatments into a blurred ascent through the clouds before the guitars shudder in for the finale. Again mystification is its mode, Bono volunteering “I have no compass and I have no map”. The music alone supplies the fuel for the flight before the freefall to a deserted aerodrome where the imagination is chalked as contraband.

Europe remains clouded in mist, a continent too disparate for any recent myths, a store house for artistic plunder where they can mock-classical intro from a Soviet collection of “Lenin’s Favourite Songs” to open “Daddy’s Gonna Pay For Your Crashed Car”. Then, for once, they don’t speak in microchip undertones as the rhythm loop hammers brutally on the anvil. “The First Time”, on Bono’s testimony originally written Al Green, gets transformed with a Velvets touch while “Dirty Day” is Bono with a touch of bitters: “If you need someone to blame/throw a rock in the air/you’re bound to hit someone guilty”.

Finally “The Wanderer” with Johnny Cash: after all the deceptive impressionism of the preceding nine tracks, Cash’s imperturbable but awkward granite integrity bounces the mood. The theme of questioning is confirmed but the record has somehow moved uncomfortably from the stratosphere to streets where an angry man might force a showdown. Till now, U2 have been avoiding, dancing round the point and dodging the bullets but even if they swathe Johnny Cash in synthesisers and Edge throws in some spaghetti Western guitar lines, Cash is more Frankenstein than Clint Eastwood and I think I still need to digest this one.

Another movie in a new cinema? Perhaps, but then the other nine tracks of “Zooropa” succeed because of, not despite, their illusions. Far more musically focused than its two studio predecessors, “Zooropa” may be the album where U2 discovered a mature style; where their lyricism found its feet on the dancefloor and they finally located a suitable basecamp to explore new horizons.

“Achung Baby” had its moments of cross-purposes but “Zooropa” blends as U2’s music becomes seamless once again. But as it shimmers, a nice bunch of guys gets confused, amused, refused, defused, bemused, used, abused and subdued by a nice bunch of girls – all dreams, I take it, for the next im(media)te point of departure.

RELATED

- Music

- 08 Apr 24

U2 digitally re-release 'Discothèque' with mixes and b-sides

- Music

- 14 Mar 24

U2 wrap up groundbreaking run at The Sphere in Las Vegas

RELATED

- Music

- 12 Dec 23

Ready For The Deal: U2 Inside The Sphere

- Music

- 05 Dec 23

U2 add 4 new dates to their Sphere run due to high demand

- Culture

- 01 Oct 23

The Vegas Job: U2 At The Sphere

- Film And TV

- 14 Aug 23

Bono charms Sarajevo Film Festival with a rendition of Bob Marley's 'Redemption Song'

- Culture

- 15 May 23