- Opinion

- 17 Sep 20

Just as Van Morrison’s ‘60s masterpiece, Astral Weeks, had been inspired by his native Belfast, it took a trip back to Ireland to conjure up his seventies highpoint, the magical Veedon Fleece. Pat Carty follows the trail.

To clarify : Van Morrison is the greatest artist of any kind ever to emerge from this island.

- Declan Lynch

By April 1971, Van Morrison was living in Marin County, just outside San Francisco, and it was here that he would build his own studio. This idyllic house on the hill, with surrounding redwood trees was a long way, literally and figuratively from his native Belfast, as the troubles flared, and an escape from the Woodstock that he felt had become a tourist attraction in the wake of the success of movie of the festival. Morrison settled in with his family, and the album released during this period, Tupelo Honey, reflected this apparent domesticity. That record’s top-thirty hit ‘Wild Night’ is always worth a spin, as is its marvellous title track, which expands on the melody of Moondance’s “Crazy Love’, and would be built on again with ‘Why Must I Always Explain?’ in 1991. Of the many cover versions, the curious are directed to turns by Dusty Springfield and Cassandra Wilson.

For most critics, and for many fans, Astral Weeks and Moondance remained high water marks. The next record, 1972’s Saint Dominic’s Preview, was clearly his best since the aforementioned pillars, combining the soul of one, with the musical questing of the other. The lyrics for the title track, a song that may well be the finest example of ‘Soul Man Van’, nod at everyone from Hank Williams to W.B. Yeats in a stream of consciousness, a technique he was not unfamiliar with if Astral Weeks is anything to go by. After the song was finished, legend has it that he saw a story about a peace mass for Belfast being held in St. Dominic’s Church in San Francisco, which informed his decision to use it as the album’s title. One of his most famous songs, ‘Jackie Wilson Said’ opens things up – and go looking for the single’s B-Side ‘You Got The Power’ - but it is the music which closes the record’s two sides that both harks back to where he had been, and hints at where he was going.

‘Listen To The Lion’ and ‘Almost Independence Day’ both stretch past the ten-minute mark. Bruce Springsteen has often been accused of ‘borrowing’ from Van, and it is hard to imagine him coming up with something like ‘New York City Serenade’ with having heard ‘Almost Independence Day’; but it is ‘Lion’ that is the album’s true golden moment. The acoustic, cymbals and bass lead texture does recall Astral Weeks, but, as the song progresses, the singer abandons language altogether, howling, moaning, searching his soul, whispering, screaming, and growling a belief in his own soul as a guide, swimming further and further into waters that only he knew were there at all.

Advertisement

One Irish Rover

Saint Dominic’s Preview was a proper hit record, giving Morrison one of the highest US chart placings of his career – he wouldn’t top it until 2008’s Keep It Simple - but the follow-up, Hard Nose The Highway, didn’t feel as driven or as focussed. There’s nothing wrong with the ambitious ‘Snow In San Anselmo’ or ‘Warm Love’, but it’s hard to understand the inclusion of a cover of the Joe Raposo-penned Kermit The Frog song ‘Bein’ Green’ while leaving out material as great as ‘Madame Joy’ or ‘Contemplation Rose’? Or maybe that’s just me: ‘Bein’ Green’ has been covered by a host of major artists, including Frank Sinatra, Buddy Rich, Tony Bennett, Diana Ross, up to Cee Lo Green an Imelda May. And if his hero Ray Charles could do it, then why not Van?

‘The Great Deception’ – a song beloved by Grian Chatten of Fontaines D.C. – doesn’t really do it for me, and that was the abiding impression of Hard Nose The Highway: it’s high points notwithstanding, it felt like a way-station rather than a landmark.

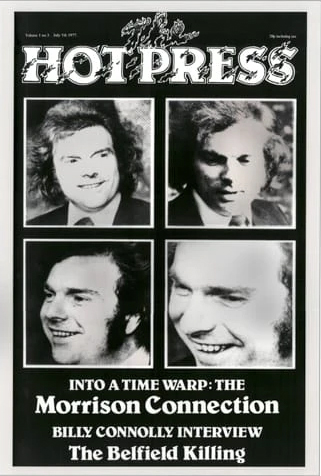

With that album out there and the touring done for now, Van decided it was time for a break, and returned to Ireland. He first lodged in Sutton with his friend Donall Corvin, where interviews were held, with the possibility of a book in mind: the interview would eventually appear in the fourth issue of Hot Press, in July 1977, with Morrison on the cover.

Van then took a hired car around the country, from Wicklow to Cork to Killarney, and also made an appearance on an RTÉ show called Talk About Pop. Before he left, he allowed himself to be photographed with a pair of Wolfhounds in the grounds of Sutton Castle. Along the way, he also wrote a few songs.

Advertisement

Before the world got to hear this new Celtic vision, there was the not-small-at-all matter of the live record. Van had put together one of his greatest ever bands in the Caledonia Soul Orchestra, a magical crew of jazzers, rockers, and string players, and the shows they played, from The Troubadour in Los Angeles to London’s Rainbow Theatre remain justifiably legendary. Though Warner Bros had previously denied him the luxury of a double album, they went with it this time around, so that it might properly reflect the extraordinary gigs he had been doing.

It’s Too Late To Stop Now is, in many ways, the early culmination of ‘Soul Man Van’, taking the R&B he had perfected on songs like ‘Caravan’ and ‘Into The Mystic’ and applied the same method to jazzier fare like ‘Cyprus Avenue’. He also found room for the likes of Sonny Boy Williamson’s ‘Help Me’ and Sam Cooke’s ‘Bring It On Home To Me’. At the centre of the whole thing was that voice, surely in the running as the finest white soul shout of them all.

As Daily Telegraph and former Hot Press man Neil McCormick replied to me recently, “he climbs right out of those songs and onto another plane.” He’s never looked cooler than he did on that cover either.

One last thing: Morrison insisted on no fiddling after the fact. There are no overdubs on It’s Too Late, unlike, say Lizzy’s Live And Dangerous. It is what it is, and this may, in part, account for its vibrancy. The story goes that ‘Moondance’ was left off because of a bum note that Morrison refused to correct. Good man.

It’s monumental. As live albums go, It’s Too Late To Stop Now is right up there with the very best of them. In fact, it might well be the best of them.

Advertisement

Avalon Of The Heart

This was from the before though, Morrison had already disbanded The Caledonia Soul Orchestra before taking that Irish trip. When he got back to California he set about recording these new compositions with a very different musical framework in mind. As It’s Too Late To Stop Now was being made ready for release, Van was already somewhere else. He worked first in his own Caledonia Studios – the Latin term for Scotland obviously fascinated him as there’s an early ‘70s outtake that goes on for seventeen minutes called ‘Caledonia Soul Music’. The acoustic, mostly one-take nature of these sessions reminded Soul Orchestra survivors David Hayes (bass), Dahaud Shaar (drums), and Jeff Labes (keyboards) of Astral Weeks, with tracks being put together on the fly. Labes added further Astral textures with inspired string and woodwind arrangements. ‘Bulbs’ and ‘Country Fair’ originated during the Hard Nose sessions, and ‘Come Here My Love’ was written during the recording. The rest of songs on the record had travelled back with him from Ireland.

Ever the contrarian, Van decided the record needed something else, and fresh versions of ‘Bulbs’ and ‘Cul de Sac’ emerged from a separate session in New York. ‘Twilight Zone’, which would have fitted nicely on Fleece, and was added to the re-mastered CD, and a song called ‘Street Theory’, which may have morphed into ‘The Street Only Knew Your Name’, were most likely recorded at the time, but left off the album. The original version of ‘Street’ is included in the very good indeed outtakes collection, The Philosopher’s Stone (1998), and is far superior to the take released on Inarticulate Speech Of The Heart in 1983.

Morrison delivered the album to Warner Brothers, and then headed back to Europe for a few live shows. The record company, anxious to give It’s Too Late its moment in the sun – it met with universal critical acclaim and strong sales – held the new album over until October 1974, or perhaps the just didn’t realise what they had on their hands.

Side one of Veedon Fleece is twenty-five of the finest minutes in the history of recorded music. “What about Astral Weeks?” you might howl. And here’s your answer: Morrison takes the atmosphere of that record and improves on it, building on its unique song-writing style. Delicately brushed drums, a dancing double-bass, acoustic guitar and piano are all that’s needed to carry Van’s remembrance of the blue lakes of Killarney in ‘Fair Play’, as he walks across meadows and down streets, taking in the architecture, man-made or otherwise. His love fills his head with Poe, Wilde and Thoreau; he’s come out the other end of marital breakdown reborn. You can hear it in the way his voice – that voice – skips joyfully through the song, his lover’s hand in his.

Labes’ first string arrangement combines with the piano and bass for a breath-taking swell of sound just after the hero of ‘Linden Arden Stole The Highlights’ takes the law into his own hands, and the heads off the lads who followed him to San Francisco, with a hatchet. Linden Arden can never rest easy again. The loneliness of living with a gun links this and the next song, ‘Who Was That Masked Man’, which explores the aftermath of violence through Van’s falsetto. You can’t trust anyone, and the ghosts come at night to drive you mad, as the acoustic guitar and strings swirl around the protagonist’s head like flies around a naked bulb.

‘Streets Of Arklow’ has Van and party again walking in Ireland – “God’s green land” - their “heads filled with poetry”. It appears that the visit to his homeland has cleansed his soul when he needed it most, as the persistent woodwind and swooping strings move about him like the spirit of the land he so badly needed to reconnect with.

Advertisement

The Philosopher’s Stone

The record’s centrepiece, ‘You Don’t Pull No Punches, But You Don’t Push The River’ closes side one, stopping just short of nine minutes. Lebes’ arrangements reach their apogee here. It begins as a love song before we head west to “get down to the real soul”. The champion of the imagination, William Blake, and his eternals are there. One presumes Morrison is more on the side of Blake’s Orc, who was the spirit of freedom, over Urizen, who pushed religious dogma as a chain of the mind. What is a Veedon Fleece? Morrison would claim in a later interview that it was just a name, but in the context of this song, and in Morrison’s work overall; it must mean something else. In some interpretations of the Greek myth, the golden fleece had powerful healing properties and Morrison’s idealised fleece must possess a similar charm, offering an artistic healing, a key to the real soul.

The song’s title, repeated at its end across the range of Morrison’s voice, has been taken as a reference to the book Don’t Push The River (It Flows By Itself) by Barry Stevens, which deals with Gestalt therapy. This form of psychotherapy focuses on the now, rather than what has or might have happened, freeing individuals from anything that might impede their satisfaction or growth. Perhaps the addition of the phrase ‘You Don’t Pull No Punches’ indicates a reluctance to just let things happen, yo just let the river wash over him? Whatever its meaning, it is song like no other, and a line can be drawn from ‘T.B. Sheets’ through ‘Madame George’ and ‘Listen To The Lion’ directly to this point. It is the purest expression of his Celtic soul vision.

Could the other side of the record live up to what’s gone before? Well, no, not quite, but then very little else has either. ‘Bulbs’ was the jaunty, country-tinged sole single released from the album, and it was backed by ‘Cul De Sac’, a ballad in ¾ time that wouldn’t have been out of place on a James Carr record. They shift the mood on Veedon Fleece, leading me to wonder would ‘Twilight Zone’ have worked better than one or the other.

The alternative take of ‘Cul De Sac’, from the original sessions, might also have been a better fit, the arrangement being more akin to the rest of the record’s mood. That’s not to question the merits of either track, however. Van could really do no wrong when a mood like this was on him.

‘Comfort You’ returns slightly to the sound of the first side and is a beautifully building thing, which none other than Nick Cave mentioned recently as one of this ten favourite love songs, and he knows what he’s talking about.

Advertisement

As for ‘Come Here My Love’, it could certainly have slotted in on Astral Weeks without anyone spotting the join, and ‘Country Fair’ takes Morrison back to Ireland again, as the sound of a lone recorder beckons Van and his love out into the cool night air of the sweet summer time, the album finishing in a similar reverie to the one with which it started.

Roll With The Punches

Even music critics get it wrong sometimes, with almost everyone panning the album when it did finally appear, with that Sutton Wolfhounds photo on the cover. Both Warner Brothers and the public reacted coolly too. There was no hit single: perhaps people were hoping for more R&B Morrison, after the success of the live album. But Van wasn’t a man to be swayed. He knew what he was doing.

There were exceptions. Nick Kent, at the NME, called it Van’s “most intriguing project since Astral Weeks.” Gradually, the album’s beauty and depth of purpose worked its spell. Clinton Heylin, in his 2002 book Can You Feel The Silence?, called it Morrison’s “great lost masterpiece.”

But, of course, it wasn’t lost. When Hot Press set about the Herculean task of getting 75 Irish artists to record Van Morrison songs, it’s striking how many gravitated to Veedon Fleece. All of the songs, bar one, were snapped up quickly; some of these versions will likely be seen as stand-out moments from the whole endeavour.

Following on from its release Van took a break, and by the time his next record appeared, 1977’s A Period of Transition, his new Celtic dawn had passed. That moment of transcendence is still available to us, however, every time we drop that needle on Morrison’s greatest achievement, his beautiful vision.

It ain’t why, it just is.

_________________________

Advertisement

The Hot Press 'Rave On, Van Morrison' Special Issue is out now. Pick up your copy in shops now – or order online below: