- Culture

- 19 Oct 21

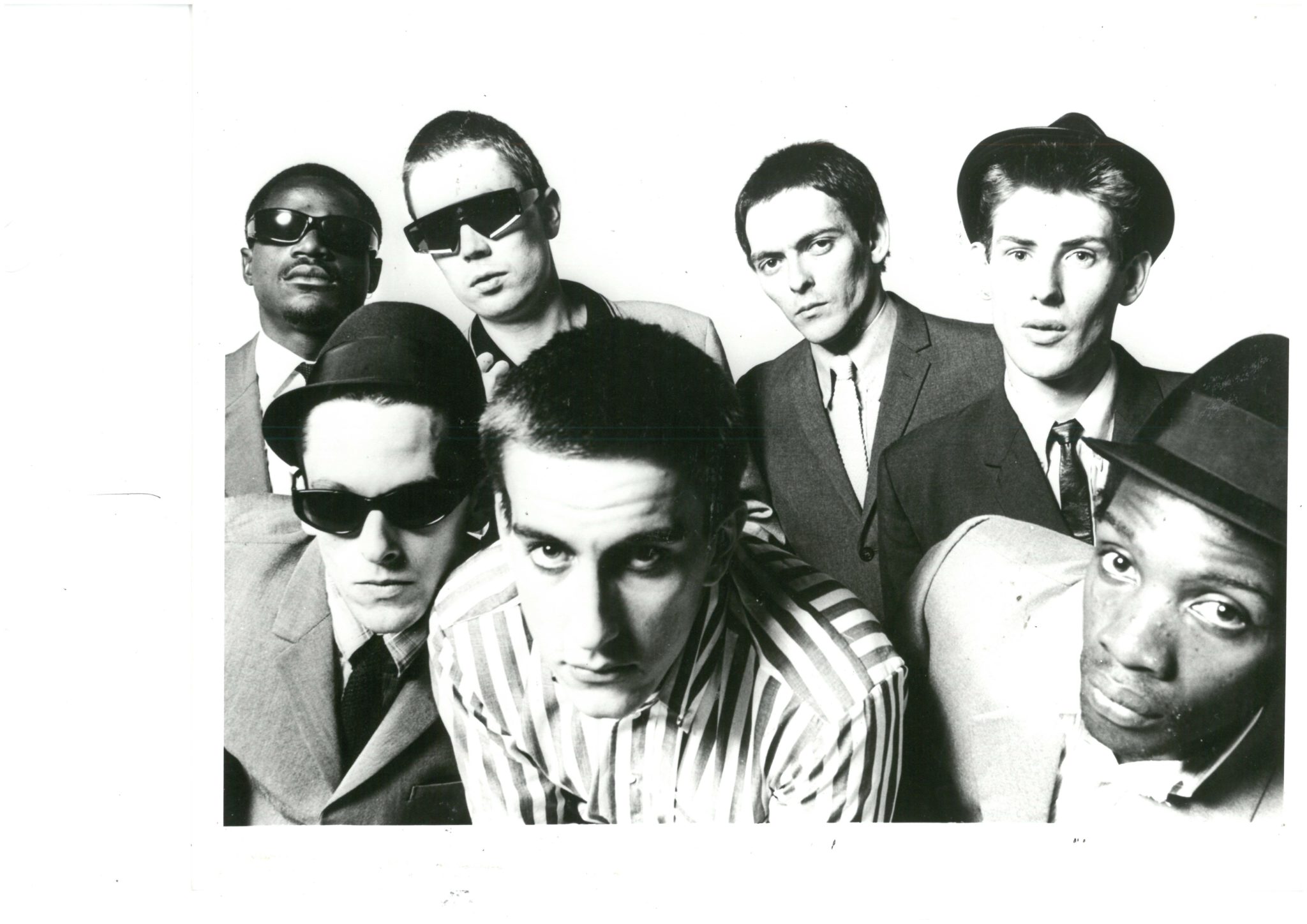

With The Specials having just dropped the urgent and timely Protest Songs 1924 – 2012, bassist Horace Panter talks politics, Irish memories, supporting The Clash, and the legacy of the classic ‘Ghost Town’.

Ska legends The Specials have returned with Protest Songs 1924 – 2012, which contains covers of songs by artists such as Bob Marley, Leonard Cohen and Frank Zappa.

At the outset of last year, the group intended to make an album of original material, but the sociopolitical tumult of summer 2020 prompted them to move in a different direction.

“In early February 2020, we talked about the idea of making a reggae record and kicked a few ideas around,” explains Specials bassist Horace Panter, Zooming from his home in the English midlands.

“But then Lynval and Nikolaj, our keyboard player, got this kind of flu thing, which knocked them for six for a week or two. And then, before you know it, there’s this thing called coronavirus. Lynval goes back to his house in America, Terry’s stuck in his house in London, and I’m up in the midlands, and we’re not allowed to go outdoors.

“So that was the end of that! But then 2020 became the year of protest, and all this stuff happened. I think that paranoia about the worldwide plague fed into it all – there was this perfect storm of people being unhappy, unsettled and dissatisfied. This worked with it, really – I don’t think we looked at it and said, ‘What the world needs is an album of protest songs!"

Advertisement

“What we needed to do was get back together and make a record for our sanity, and we chose to make an album of protest songs in order to do that. It was much therapy as it was a public statement.”

The Specials have taken an imaginative approach to the album, choosing tracks – such as Cohen’s ‘Everybody Knows’ and Talking Heads’ ‘Listening Wind’ – not usually noted as protest songs.

“We didn’t want to go for the obvious choices,” says Horace. “I mean, I will put my hand up and say, ‘Yes, there is ‘Get Up, Stand Up’ by Bob Marley.’ But I like to think the way we’ve approached it has been different. Yes, it would have been easy to do a version of ‘Give Peace A Chance’ or Barry Maguire’s ‘The Eve Of Destruction’. But we thought, let’s dive in and make it a bit more obscure, almost like you’re doing a thesis or something.

“So we’d research the background, which I actually found really interesting: going back and reading about the songs, where they were recorded and where they came from. We ended up with something like ‘My Next Door Neighbour’, an insane blues tune which was on an album called Songs Of Protest And Complaint, which was issued by the American Library of Congress. The song was recorded in 1955 and the album was released in ’77.”

There were other revelations for the group.

“When it came to Malvina Reynolds, I’d known the song ‘Little Boxes’,” Horace continues. “It was on the radio when I was eight, and I’d always known Pete Seeger had sung it. But I didn’t know it was written by Malvina Reynolds, and I certainly didn’t know she’d written all these other tunes that are extraordinary. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard her, but she’s got this extraordinary whiny voice; it’s like there’s a Martian singing, not that I’d know what a Martian sounds like! But what incredible songs.

“So again, it was kind of weird stuff that we wouldn’t normally listen to, and stuff that was recontextualised. The Specials would get a song like ‘Monkey Man’ and turn it into a protest song, because it was about the bouncers. Or ‘A Message To You, Rudy’. We had that track record, so we could do something like Leonard Cohen’s ‘Everybody Knows’ and make it a protest song, or a fantastic Chip Taylor tune like ‘Fuck All The Perfect People’, which was just made for Terry to sing.

Advertisement

“I think I personally learned an awful lot about music in choosing the songs and recording them.”

Ever since their early days in the punk movement in the late ’70s, there’s been a political element to The Specials’ music. I’m not surprised they turned to it in summer 2020, which was definitely the darkest period in the world in my lifetime.

“Me too,” nods Horace. “Above all, I was just concerned. I’m nearer 70 than I am 65, and I was recently handed a granddaughter. I’m perhaps concerned about the world that she’s going to grow up in, but we shall see. I do agree with you though, it was just awful.”

POLITICAL COMMENTARY

The recent 20th anniversary of September 11 of course prompted recollections of that dark and tragic time, when the sense of dread was suffocating. I’d hoped never to experience that feeling again, but in the early days of Covid it returned – except this time stretched over several months.

“Yeah, that whole lockdown period,” Horace reflects. “We’d recently moved out of Coventry – we now live in the countryside, so in a way the first lockdown was lovely! The weather was great and whatever, but during the second lockdown, the weather was miserable and so were we. It wasn’t much fun, and then you had the machinations of Brexit, blah-blah-blah.

“And also the arguments about vaccinations and everybody being at each other’s throats… It was weird, really strange. But I do remember where I was on September 11, and where I watched the TV and saw that shit happening.”

It’s quite incredible that exactly 20 years later, the Taliban are taking over in Afghanistan again.

“It’s funny, my mother was born in Peshwar, which is now in Pakistan,” notes Horace. “My father was an army schoolteacher, and I remember my mother saying to me, ‘Your grandfather would have violently disagreed with people going into Afghanistan. You should leave people alone.’ The one thing we learn from history is that we never seem to learn from history.”

Advertisement

Given the sharp level of division in the world recently, The Specials’ brand of political commentary feels more relevant than ever.

“Yeah, what happened?” muses Horace. “Where’s the band that does what The Specials did? I have asked this question, Paul, for decades. Where’s the band we can hand our baton over to? There may very well be people who are doing this, but I think it’s probably the fact that I don’t listen to a great deal of contemporary music. Perhaps I’m missing them, perhaps they are out there – it’s just I don’t subscribe to their YouTube channel or whatever.”

Certainly, lot of the great bands around currently aren’t operating anywhere near the mainstream, and it’s difficult to imagine a song like ‘Ghost Town’ getting to number one these days.

“Sure,” agrees Horace. “But I think that’s as much to do with how music is contextualised, and how important it is in a social strata. When I was at school, you get beaten up if you bought a Deep Purple song. I don’t know if music has that cache nowadays – perhaps a new pair of trainers means more than if you like a particular kind of music. I don’t know, I find it weird.

“People can sell out arenas and I’ve never heard of them – but I’m not 14 and on Snapchat or whatever, do you know what I mean? I really don’t know who Dua Lipa is. I’m sure she’s wonderful, but I’m divorced from all that. I would not like to be in my teens with a load of good songs and a guitar. But there is always that amazing thing when you get a guitar, and you put your fingers on the fret and go, kerrang! The noise and the effect that it has, that’s always going to be there.

“In that respect, I have great belief in the power of music; that young people can learn instruments and interpret music. It’s a great form of expression. Apart from it being an enormous amount of fun, you can actually use it to say something. Music will change the world – Horace Panter says that!”

Horace may say that in jest, but as someone who grew up listening to bands like Nirvana and The Sex Pistols, I have to say they did influence my political and cultural outlook to a remarkable degree.

“Well, music is something you can nail your cultural colours to,” considers Horace. “Going back to getting beaten up for having a Deep Purple album, in the ’60s you were a mod or a rocker. The music defined who you were, because there wasn’t as much choice. You either dug Gentle Giant or you liked T-Rex. If you liked T-Rex, you knew what sort of person you were, the same with Motörhead. I don’t know, I think I’m disappearing up my own arse here a bit, Paul!”

SUPPORTING THE CLASH

Advertisement

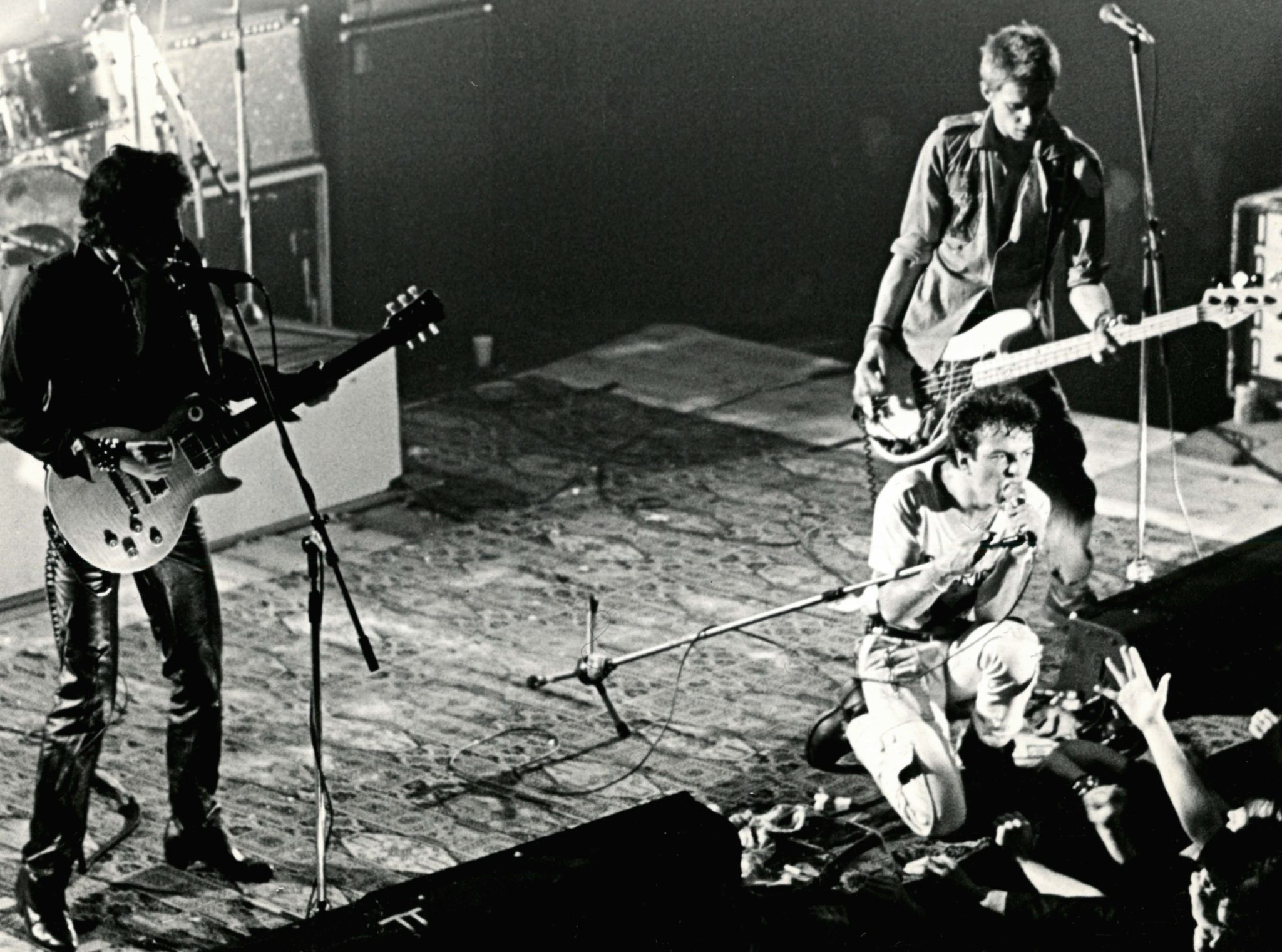

Not at all, Horace! To delve deeper into the punk era, in their early days, The Specials – who formed in Coventry with the mordantly witty Terry Hall as frontman – supported The Clash on tour, which is as tasty a bill as you’ll ever come across.

“Up until that time, that was the greatest thing that had ever happened to me in my life,” Horace enthuses. “I always say that in 1978, we started that tour as civilians, but ended it as a group. It was our rock and roll boot camp – it was great fun, absolutely amazing. I think we made 12 pounds each for the whole tour, but it was fantastic.

“Everyone goes on about ska, The Skatalites, Bob Marley & The Wailers, 2-Tone and The Specials, but we owe an enormous amount debt to The Clash, because they showed us how to present a show. You go onstage and you give 110 percent every night, all night. That set the bar for The Specials, and then the next year, we came out and did ‘Gangsters’. We went on tour, and played a lot of the places we had played as support for The Clash. It was quite an achievement. I was very upset when I heard that Joe Strummer died. That was another of those ‘Do you remember where you were?’ moments.”

With The Specials having visited Ireland quite a bit over the years, I wonder if Horace has any particular memories of playing here?

“I’ve always enjoyed it,” he replies. “I have this art career that goes in parallel with the music stuff, and I exhibited in a gallery there called E-Bow at one point. That’s always been good fun, to get something other than just the music going over in Dublin. We also had this thing called The Specials Mk2, which was Neville, Lynval, Roddy and I, and we would do Midnight at the Olympia on a Saturday. That was wild, absolutely amazing.

“We’d load in after The Pirates Of Penzance or something at half-past 10. They’d open the doors at 11 and every drunk in Dublin would arrive! We would go onstage at about half-12 or one in the morning, and it was absolute mayhem, it was lovely. I remember a security guy standing down the front looking at us, going, ‘Play a ballad! Play a ballad!’ But we’d just be like, ‘Sorry mate’ and do ‘Concrete Jungle’!

“Afterwards, we’d load up the coach to drive back to Dun Laoghaire, and there’d be a half-mile queue for taxis at about 4.30 in the morning. It was wonderful.”

Advertisement

SPECTRE OF GREATNESS

Finally, I ask Horace about the legacy of ‘Ghost Town’, the suitably eerie dub tune which soundtracked a particularly fraught time in Thatcherite Britain, when the social fabric was seriously starting to fray. Topping the charts in summer 1981, it is unquestionably one of the greatest ever UK number ones. What does Horace think of it now? And has he seen its famous use in Father Ted?

“Loads of people have mentioned it,” he laughs, “but I haven’t seen it! I think I know what happens, cos all these people have told me. In terms of when it was released…the band were falling apart when we recorded ‘Ghost Town’. Just the fact it was recorded was actually a miracle, but it was a triumph of the will. It was not a good time, so in that respect it’s not a great memory. But it was a fantastic piece of music. I love the fact that it was recorded in a tiny little basement, in an eight-track studio in Leamington Spa.

“And then it was produced on four-track in the producer’s front room in Tottenham. That was a time when other people were going to the Bahamas and recording on 48 tracks – it was all that extravagant, waste-of-money, music business stuff. And yet, we go to our reggae roots and record something very primitively. But it was a great song and a great idea.”

Horace still takes notable satisfaction from the song’s achievements.

“I am very proud of how it was manufactured, definitely,” he says. “Hindsight has made it a lot more important than I think it was at the time. When it first came out, I was sitting in my flat in London Road in Coventry, and watching the TV and seeing all these riots in Bristol, Liverpool, London – and this was at number one. It was very scary, it reminds me a little it of what we were talking about earlier, about 9/11. It’s like, ‘What the hell?’

“My song was the soundtrack to this, and it was kind of weird. But you’re right – it wasn’t entertainment in a way, it was a social comment. It was more than music, I think. I don’t think pop music has captured that again. I’m sure someone will prove me wrong!”

Advertisement

I make the point to Horace that it’s amazing how, so often, great art – whether it be a song, a movie, a TV show – arises out of the most difficult of circumstances.

“Yes, groups are always about people skills,” he says. “When people say, ‘Oh, they left because of musical differences’, they’re lying. But that’s the thing – you go through all these extraordinary emotional highs together. Performing is an incredible thing, it’s an aphrodisiac; you can leap tall buildings with a single bound because of all the adrenaline. And then someone gives you some drugs… Terry said one time, ‘Cocaine turns a wanker into an even bigger wanker.’ I thought that was really cool.

“You become a different person to who you were, when you didn’t have anything and wanted to be in a group. Some people change a lot and some people don’t change that much. If you’re a bunch of drunks before you get in a band, it’s no big deal. But if you weren’t a drunk before, and somebody becomes more of a drunk, those things highlight it. You just fall out of love with people. And there’s all the other stuff as well, like how the drummer’s girlfriend might fall in love with the singer! That’s what happens.”

• Protest Songs 1924 – 2012 is out now.

Read the Hot Press verdict of the album here.