- Opinion

- 21 Aug 24

From the Archives: 14, Irish, Raped, Pregnant, and a Prisoner

It was one of the most shocking outcomes of the introduction of the so-called 'Pro-Life' 8th Amendment to the Constitution in 1983, that a 14 year-old girl was prevented from travelling to the UK for an abortion, necessary as a result of statutory rape by a neighbour. The judgement to prevent her having the procedure carried out was delivered by the High Court in February. It was appealed to the Supreme Court, which announced its verdict on 5 March 1992. In an article that we made the cover story of our issue on 27th February, Nell McCafferty reflected on a controversy which convulsed the nation, and suggested that, in time, the option of abortion – difficult as it might be – would have to be made available to Irish women. It took until 2018, when 66.4% of Irish people voted to repeal the 8th Amendment, enabling abortions to be carried out legally in Ireland...

AND IT got worse. At the end, the nation was locked out, while five men met in conclave to decide what would be

done with her. No-one will ever know what was said in secrecy in the Four Courts about her, as her life hung in the balance.

Not the church, not the state, not even the female to decide her fate: she wasn't there, nor required to be there, and if she

had insisted on being there, she would not have been allowed to speak. At the end, her human person was merely academic. Her

very gender was taken from her. In the published banns of the court she was listed as "X", a subject of adversarial discussion

between men.

The men walked into X's womb, took a stroll around X's brain, stretched X's body on an international legal rack and took measure of how X might stand the strain of that. A butterfly was tested on a wheel.

Beyond the Irish Four Courts, the rest of the entire European Community waited, for upon the contents of X's womb, this raped child's womb, rested the fortune and fate also of France, Germany, Portugal, Greece, Italy, Belgium, Holland, Spain,

Luxembourg, Denmark and the United Kingdom. These countries, with Ireland, had designed an agreement at Maastricht that would bind them together, one for all, all for one, and that agreement contained a protocol which endorsed Irish ways and Irish laws on abortion.

The original Hot Press feature in 1992

The original Hot Press feature in 1992Were the Supreme Court to uphold the child's constitutional internment, and force her to give birth, the subsequent signing of the Maastricht protocol on behalf of other European people would mean that they, too, endorsed her crucifixion. Were the Supreme Court to set the child free, the Maastricht protocol, having international superiority, would over-rule that decision, and oblige all of Europe to support further Irish efforts to chase and detail other raped, pregnant, girls.

The other countries of Europe have indicated their aversion to such cruelty. They are poised to expel Ireland, to put it beyond

the pale. Ultimately, then, no matter what the Supreme Court decides, it will come down to a vulgar discussion of which

matters more: the headage payment for pregnant ewes, or the preservation of a human female's forcibly fertilised ovum. Signs

are that the sheep will be deemed of greater value. Signs are that abortion, in some restricted form, will be legalised in Ireland and interim freedom to travel abroad for abortion will be welcomed by the Irish people.

Not the church, not the state, the animal farm will dictate our fate. The gadarene rush began when the government pleaded with the family of the raped girl to take the money and run back to court.

LESS THAN SIX MINUTES

I saw an abortion performed In a clinic in North Queensland, in Australia, in 1985. The conclusion of the Kerry Babies tribunal had just been published. Asked to inquire into how guards had wrongly proferred a charge of infanticide against a woman, Judge Kevin Lynch found that the woman was to blame. In Australia, people were wondering how he had come to that decision. They wondered, also, how we had come to decide by referendum that a fertilised ovum had equal status with women and girls.

Australians professed not to understand these things, though they too had their own problems. They had just convicted a woman of infanticide, and poured legal scorn on her explanation that a dog was to blame. The Dingo Baby case was a source of anguish to them. And in Queensland, where I was, the state was in uproar over abortion.

It was legal, but not available in hospitals, and moves were afoot to have it made illegal in private profit-making clinics. Many of these clinics were under picket siege by anti-choice fundamentalists. The governor of the state gave it as his public

opinion that abortion in any circumstances was murder. (He was later indicted for bribery and corruption, which just goes to show that none of us is perfect).

Feminists in the town where I saw the abortion performed were caught between a rock and a hard place. They had a visceral dislike of the doctor who ran the private abortion clinic. They worried about counselling women to go to him for

pregnancy termination.

How did he treat them? What was his attitude to these women? And what could they do about it, since his was the only clinic serving a geographically huge area? The doctor had refused to discuss their concerns.

At first sight, the doctor was a legitimate source of worry. For some confusing reason, he had been appointed my host on this

leg of a speaking trip, and he had come to meet me at the tiny airport and his appearance was an exact caricature of the

demonised masters of abortion-mills, beloved of fundamentalists. He wore a floral shirt, unbuttoned to the waist. A gold

medallion nestled in the abundant hair on his chest. Gold rings and a gold watch glistened about his hands. He drove an open-topped red sports car.

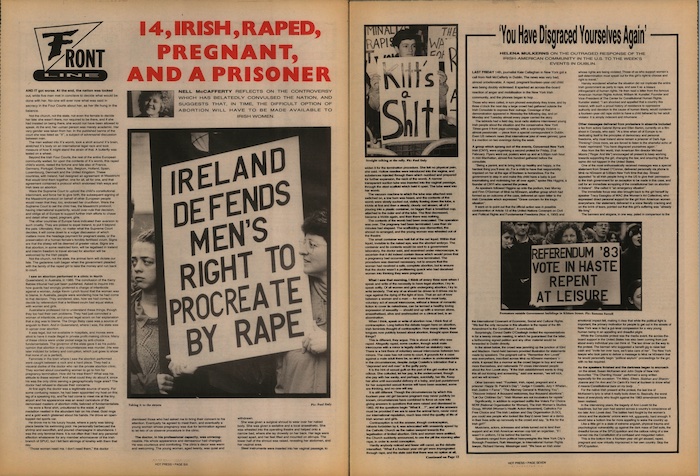

Talk it to the streets / Pic: Paul Daly

Talk it to the streets / Pic: Paul DalyHe drove me to his luxury house, where a party was taking place beside his swimming pool. He personally barbecued the

shrimp and swordfish, and poured champagne in abundance. I was the only feminist there. It is not often that I feel any personal

affection whatsoever for any member whomsoever of the Irish branch of SPUC, but I felt faint stirrings of kinship with them that

day.

"Those women need me. I don't need them," the doctor dismissed those who had asked me to bring their concern to his attention. Eventually he agreed to meet them, and eventually a young woman whose pregnancy was due for termination agreed to let two of us observe the procedure in the clinic.

The doctor, In his professional capacity, was unrecognisable. His whole appearance and demeanour had changed.

He was courteous and comforting. The clinic's decor was warm and welcoming. The young woman, aged twenty, was quiet and withdrawn. She was given a surgical shroud to wear over her naked body. She was given a sedative and a local anaesthetic. She

was wheeled into the operating theatre and helped onto a narrow bed, where she lay drowsily on her back. Her legs were

spread apart, and her feet lifted and mounted on stirrups. The lower half of the shroud was raised, revealing her abdomen, and

her vaginal area.

Steel instruments were inserted into her vaginal passage, to widen it for the termination procedure. She felt no physical pain, she said. Hollow needles were introduced into the vagina, and substances injected through them which numbed and prepared

for further expansion, the neck of the womb. A narrow transparent suction tube was inserted into the vagina passage, through the steel scaffold which held it open. The tube went into her womb.

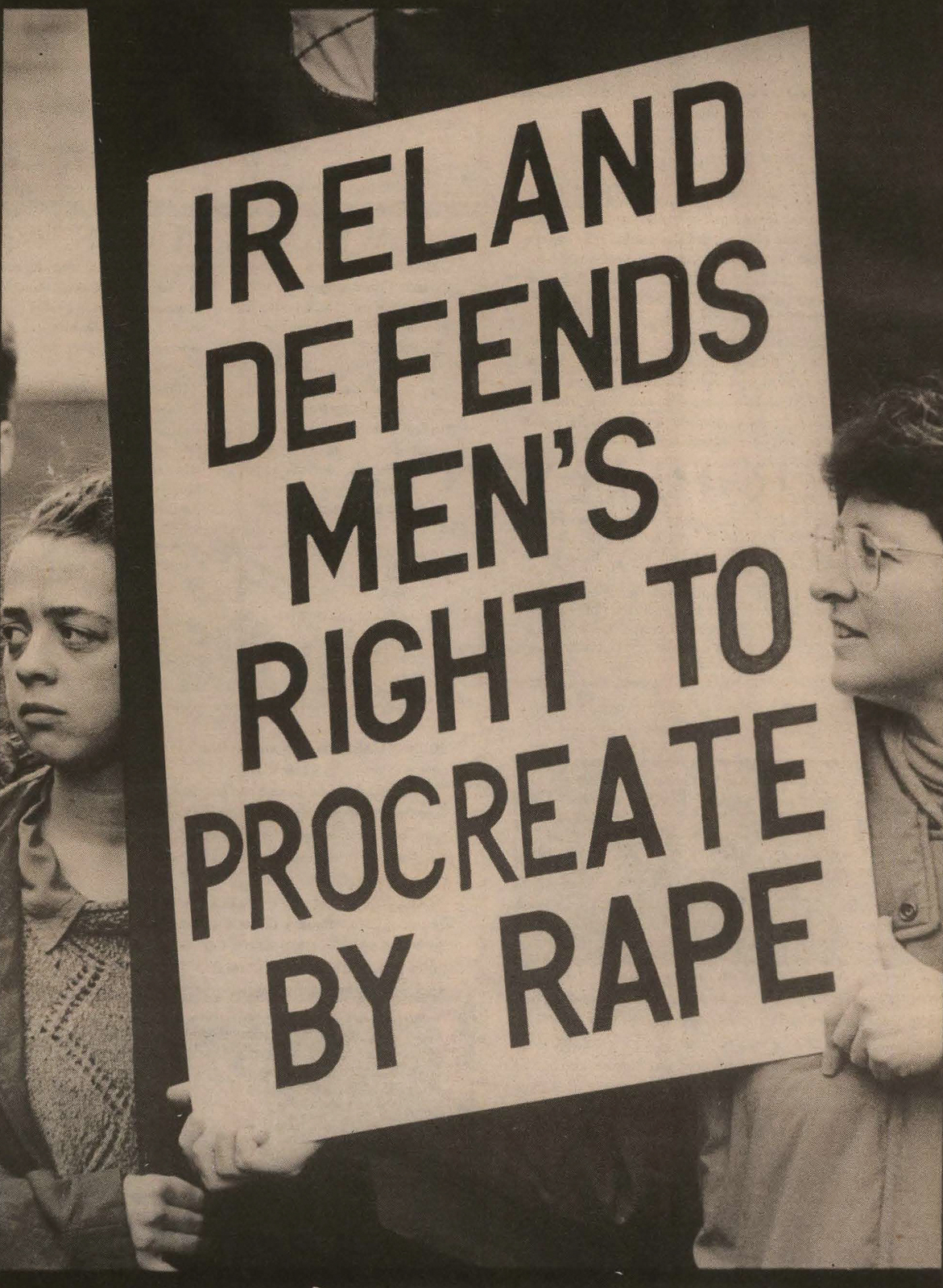

Straight talking at the rally / Pic: Paul Daly

Straight talking at the rally / Pic: Paul DalyThe vacuum machine to which the tube was attached was switched on, a low hum was heard, and the contents of the womb were slowly sucked out, visibly flowing down the tube, a trickle at first and then a steady. cloudy red stream, all of it pouring into a plastic container, no bigger than a breakfast cup, attached to the outer end of the tube. The flow decreased, became a trickle again, and then there was nothing.

The contents of the womb had been evacuated. The operation was over. The pregnancy had been terminated. Less than six

minutes had elapsed. The scaffolding was dismantled, the shroud re-arranged, and the young woman was wheeled out of the theatre.

The small container was half-full of the red liquid. Within that liquid, invisible to the naked eye, was the aborted embryo. The

container and its contents would be sent to a government laboratory, the doctor said, and examined under microscope, to ascertain that it did indeed contain tissue which would prove that a pregnancy had occurred and was now terminated. The procedure was deemed necessary, not to ensure that the woman had received a safe, complete abortion, but to ensure that the doctor wasn't a profiteering quack who had deceived women into thinking they were pregnant.

The original Hot Press feature in 1992

The original Hot Press feature in 1992FORCED IMPREGNATION

What I saw that morning, I think of every time now when I speak and write of the necessity to have legal abortion, I try to speak softly. Of all women and girls undergoing abortion, I try to write tenderly. That any of us should be driven to it drives me to rage against the dying of the light of love. That an act of love between a woman and a man - for even the most lusty,

voluntary act of sexual intercourse, without a tissue of romantic fiction to cover its nakedness, can be termed a healthy loving expression of sexuality - should end up with a woman alone, anaesthetised, alive and enshrouded on a clinical bed, is an

abomination.

When I think, speak or write of abortion now, I think first of contraception. Long before the debate began here on abortion,

Irish feminists thought of contraception. How many others, their tongues now publicly loosed about abortion, thought upon these

things?

This is different. they argue. This is about a child who was raped. Allegedly raped, some caution, though adult male intercourse with a minor is legally defined as statutory rape. There is a hint there of voluntary sexual intercourse between two minors. The case has not come to court, if grounds for a case against a male adult there be, so strict caution is understandable in the circumstances, despite Judge Costello’s intimation in the High Court that a "depraved and evil man" is the guilty party.

It is the hint of sexual guilt on the part of the girl-mother that is odious. She colluded, let her pay, is the undercurrent, though she pay with her sanity, and perhaps, suicidally, her life. Keep her alive until successful delivery of a baby, and just punishment for her suspected sexual license will have been exacted, some are thinking, and no-one will say.

It is still different. Though the circumstances by which this fourteen year old girl became pregnant may never publicly be

known, circumstances have combined to force us now into giving answers to questions that were raised and dismissed in 1983.

All the questions begin "'What if .. ?", and all the answers must be provided if we are to save the animal farm, never mind

our international reputation, much less mind the quality of life of Irish women and girls.

Contraception is not the answer, though contraception, hitherto forbidden by it, was advocated with unseemly speed by the Catholic Church as the nation swayed towards the legalisation of limited abortion. Girls and Woman were entitled, the Church suddenly announced, to use the pill the morning after rape, in order to avoid conception.

Hardly anybody noticed and fewer still cared, as the debate intensified. "What if a fourteen year-old girl were impregnated through rape, and the state said that there was no option at all,

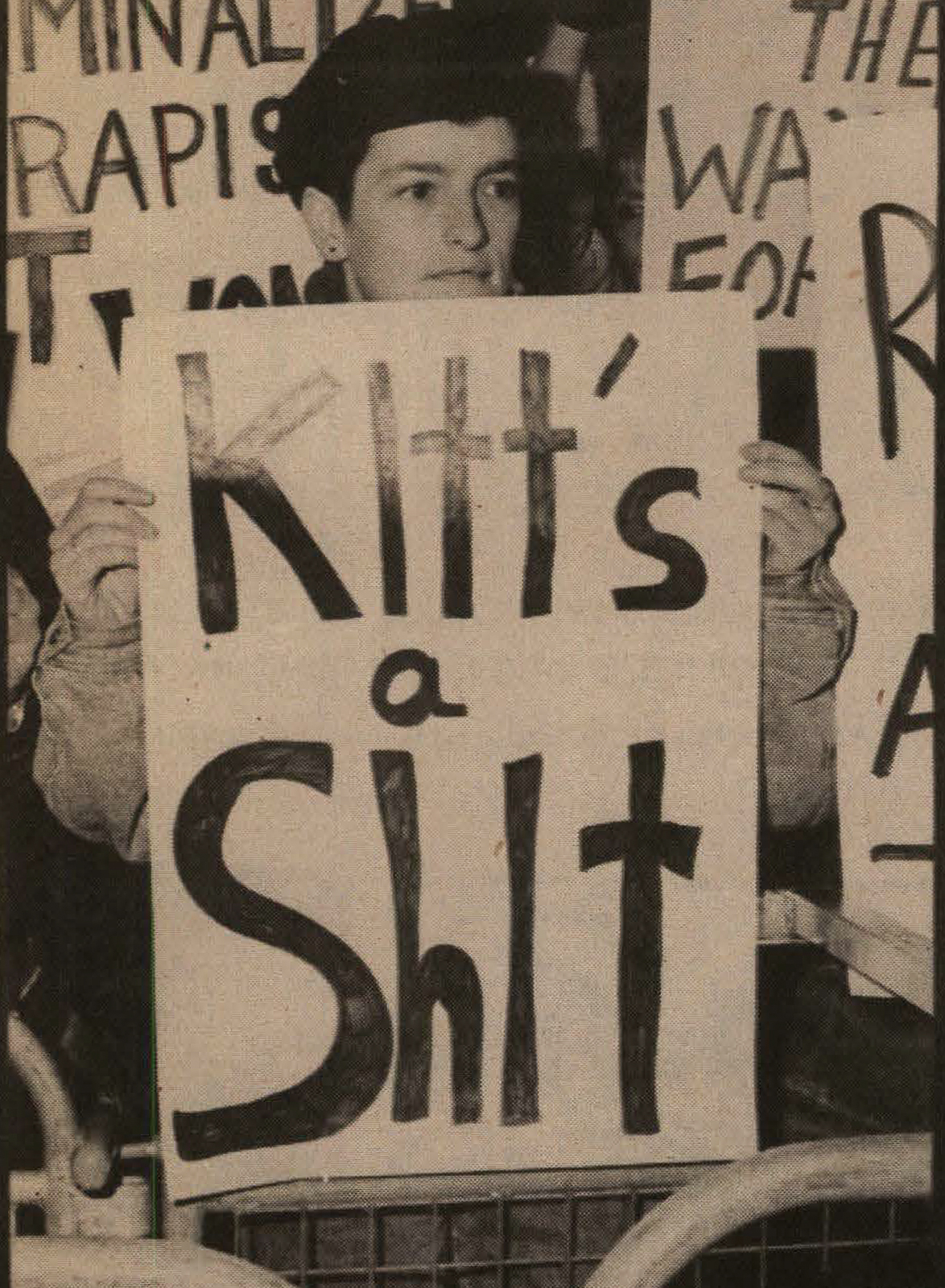

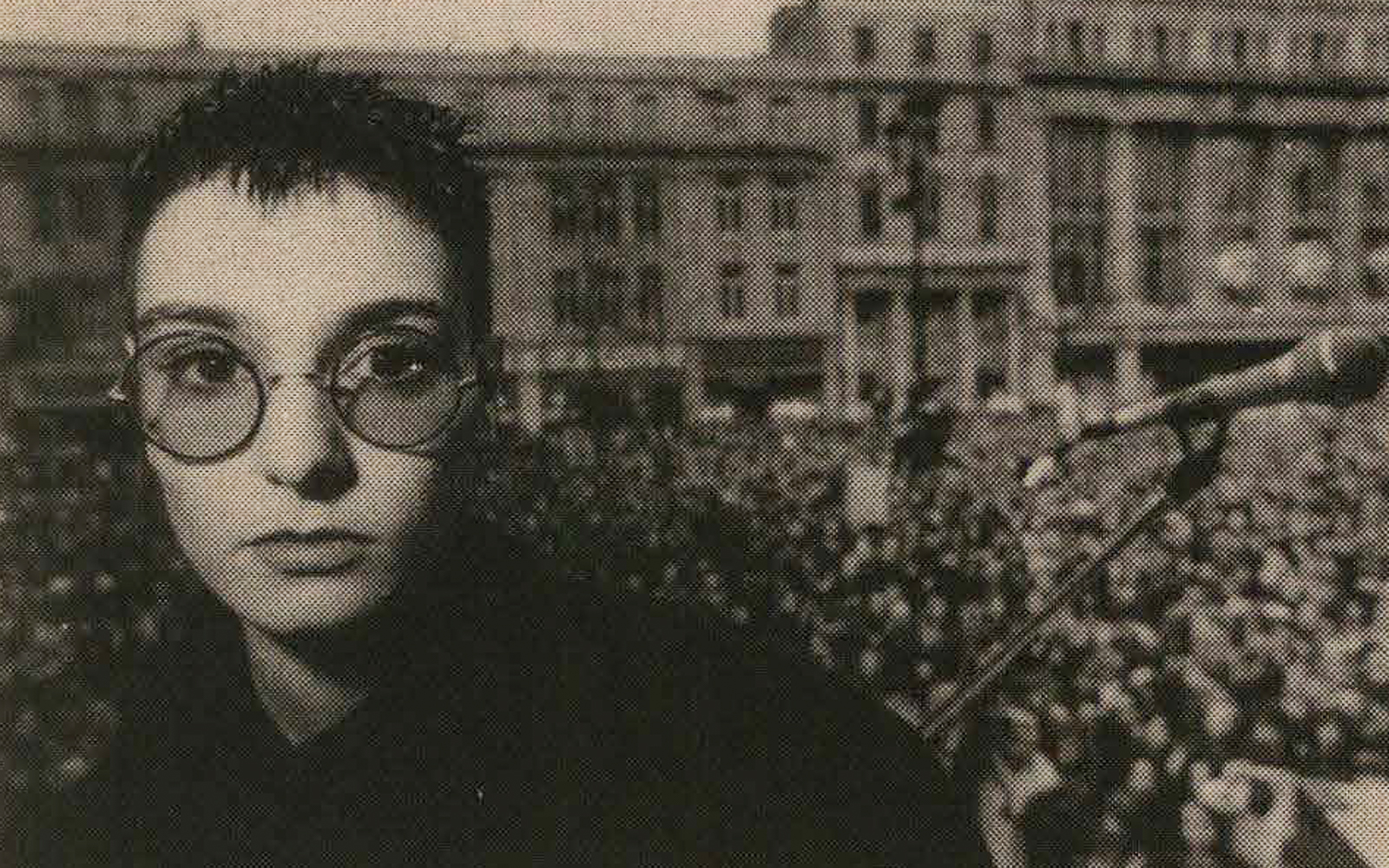

Sinead O'Connor at the recent rally in Dublin in support of the 14 year old rape victim / Pic: Paul Daly

Sinead O'Connor at the recent rally in Dublin in support of the 14 year old rape victim / Pic: Paul DalyIrish girls have been raped and impregnated, long before 1983, long before England provided merciful salvation through legal abortion in 1967. There were 49 births arising from sex with minors here in 1955, the first year they were counted officially.

Were they all little Lolitas? Was there no known forced impregnation of the young, through rape or incest, in Ireland, until Friday morning, February 7th, 1992, when the Attorney General went into court and sought an injunction against the girl called X?

A HOLDING OPERATION

In 1990, It was established in our courts that three individual girls under the age of 15 had been raped and impregnated, and convictions against the rapists were obtained. The government knew, successive governments have known, of these matters. So did doctors, TDs, churchmen – so have most of us. As all have known of the flight into England.

Now the world knows, and anti-choice fundamentalists were among the first to shamefully cry out that it was never meant to happen this way, that they didn't try to stop minors in flight out of Ireland. Not us, they said, and not a blush on them. There's hardly been a blush in the land, as people come forward to imply they'd never realised before, never thought before, what it must be like to be raped, and pregnant, at 14, and denied abortion.

What an unimaginative people, how incapable of thought, we have turned out to be. How close to the ground, we have shown, were our knuckles in 1983, when we walked about, beat about, the bush. How sly we proved to be, might prove to be again, as the country un-furrows its neanderthal brow and posits a single answer to all 'what-if' questions regarding the female of the species: a scratch under the constitutional armpit, accompanied by a legal grunt from the Supreme Court, would be understood by those in the know, the inhabitants of the EC subsidised Irish animal farm, to mean what it does not say it means. Freedom to

travel would mean abortion.

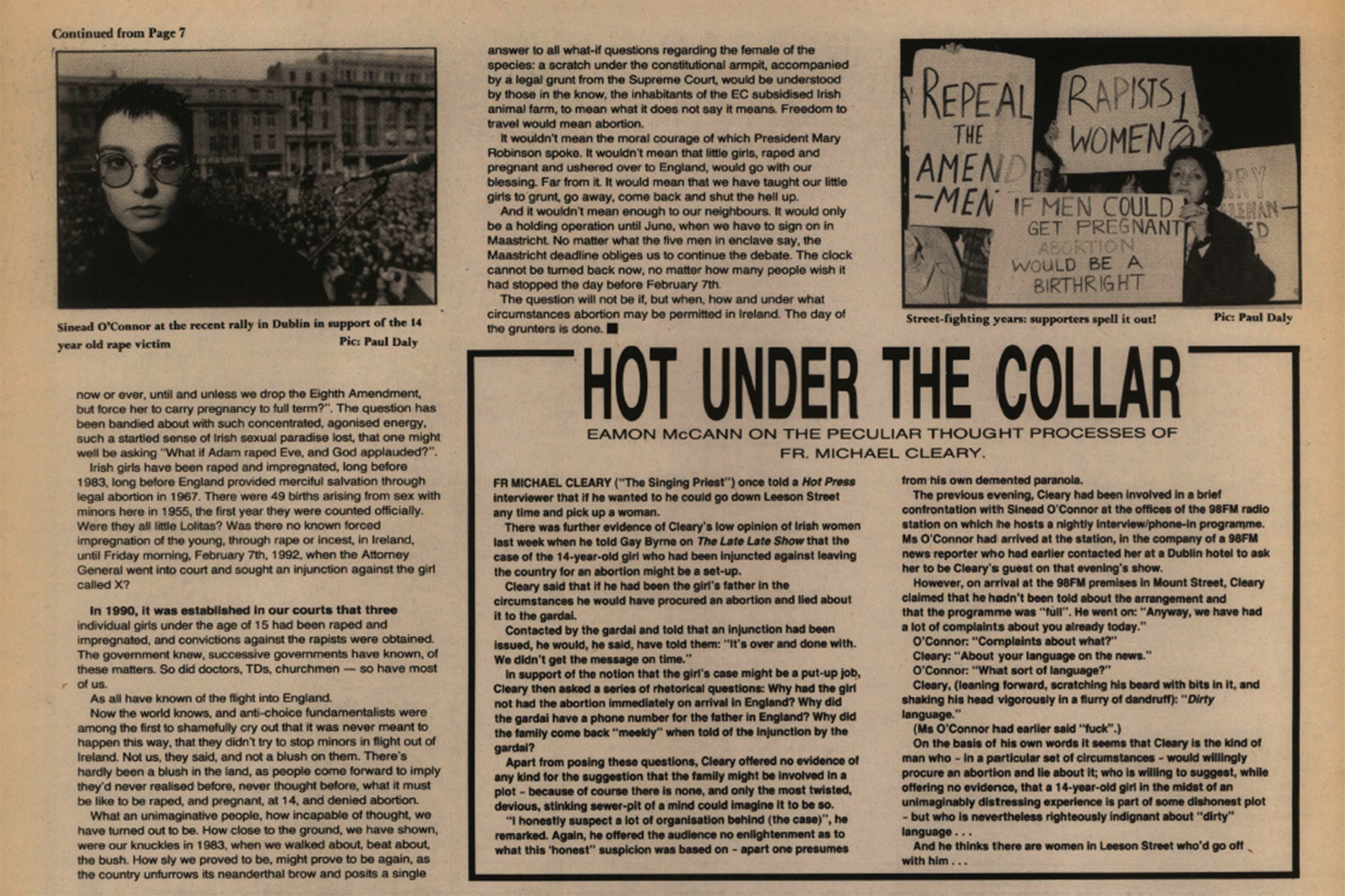

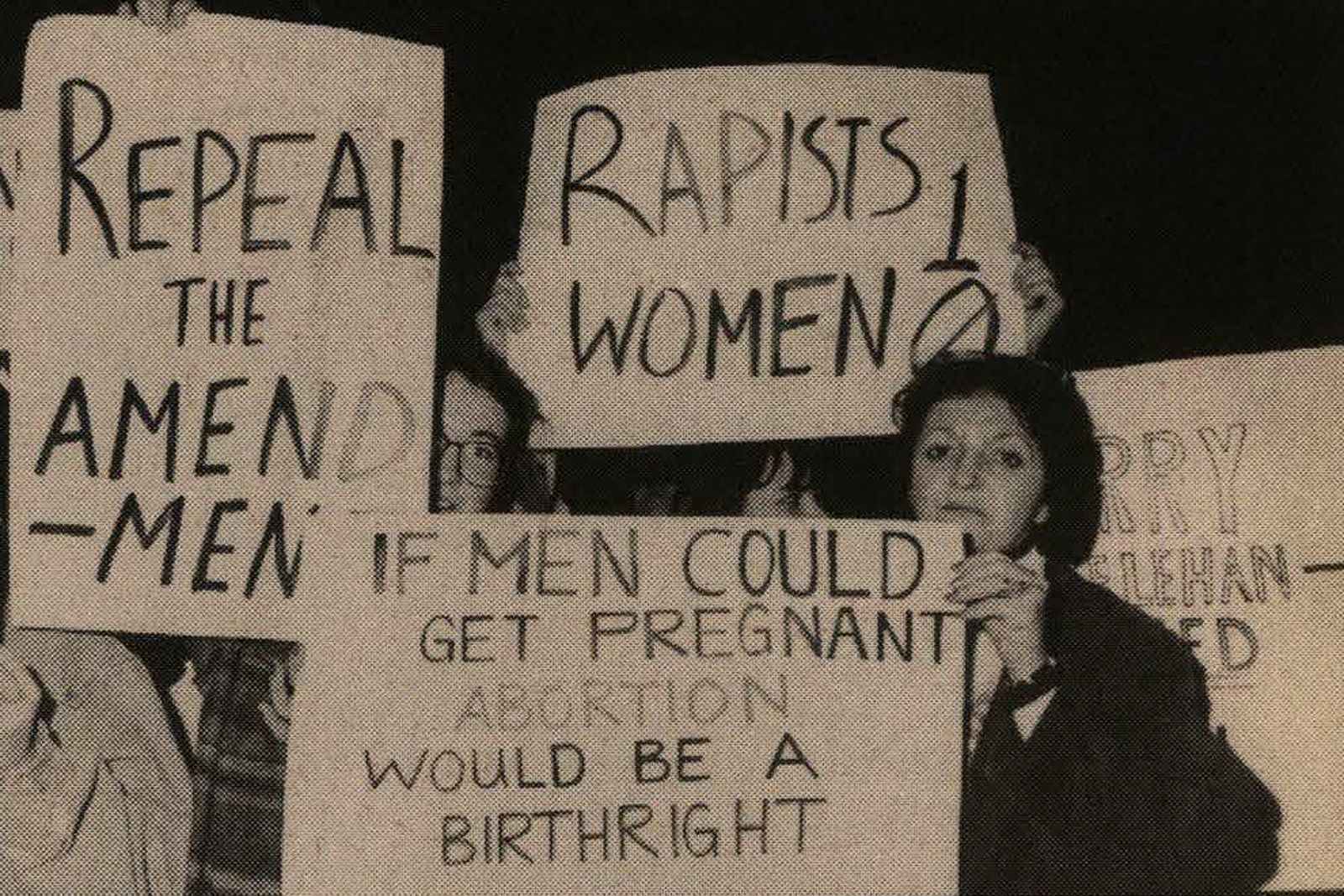

Street-fighting years: supporters spell it out! / Pic: Paul Daly

Street-fighting years: supporters spell it out! / Pic: Paul DalyIt wouldn't mean the moral courage of which President Mary Robinson spoke. It wouldn't mean that little girls, raped and

pregnant and ushered over to England, would go with our blessing. Far from it.

It would mean that we have taught our little girls to grunt, go away, come back and shut the hell up. And it wouldn't mean enough to our neighbours. It would only be a holding operation until June, when we have to sign on in Maastricht.

No matter what the five men in enclave say, the Maastricht deadline obliges us to continue the debate. The clock cannot be turned back now, no matter how many people wish it had stopped the day before February 7th.

The question will not be if, but when, how and under what circumstances abortion may be permitted in Ireland. The day of the grunters is done.

- This article was originally published in Hot Press 16.04, 27th February 1992. Where relevant, the captions are the originals from the 1992 article.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 03 Sep 24

A Word to Students: On the Legacy of Nell McCafferty

- Opinion

- 21 Aug 24

Nell McCafferty: A tribute to "The Ultimate Irish Feminist"

- Opinion

- 21 Aug 24

Tributes continue to pour in following death of Nell McCafferty

RELATED

- Opinion

- 21 Aug 24

Feminist campaigner and journalist Nell McCafferty dies aged 80

- Opinion

- 28 Jan 26