- Opinion

- 07 Jul 21

A Conversation Between President Michael D. Higgins and Denise Chaila: "You Cannot be a Tourist of The Revolution"

"I knew how I didn't want to write this piece: 'A rapper and the President of Ireland walk into a pub – what happens next will shock you!' A gag."

“I define a republic as a community of vulnerabilities recognised. That’s my definition of it. That a republic is a community of vulnerabilities adequately recognised.”

It’s May 2021 and President Michael D Higgins is talking politics. Except not quite. He’s talking poetry and humanity and principle, and allowing that to be his politics. I strive to operate intimately with words; to open them up, learn how they work and use them better. Sometimes that means doing some research about the history of a word. It reveals a lot more than Merriam-Webster might.

For example, the word ‘toxic’ has more to do with archery than poison, there’s a hilarious relationship between avocados and ‘testimonies’, and the word poetry comes from a Greek word meaning ‘to create’ more than it means to write verse.

This word, ‘vulnerable’, it comes from a Latin word which means ‘wound’.

Understanding this, I believe vulnerability means, to bare your wounds to someone trusting that you will not be further wounded. That you will not be attacked. This is what we do when we submit to medical care, when we submit to the necessary violence of a surgeon’s knife knowing that though the process is painful, the intention is to save our lives. The mortifying ordeal of being truly known in service of community care.

“The business of being able to put yourself in the space of the other, this is what actors can do,” President Higgins says. “This is what great singers can do. And the risk is that it might not work for you sometimes in relation to the performance and so on. But that is the intention.”

I sat with Jafaris in the National Concert Hall last September and I remember talking about big dreams. Skip a few months and he featured on a remix of ‘Anseo’ talking about “if I could get Michael D on the phone, I’d tell him ‘fair play’...”. Things manifest in surprising ways because it’s May and here I am sitting with the man himself, on a Friday afternoon, exchanging books. Exchanging honesty and fire.

Interviews are trust falls. Trusting that you will be held fairly within the lens of another person’s perspective is vulnerability. Trusting that they will not declaw you, sterilise your intent, and censor you is vulnerability. Trusting your convictions as a writer, knowing you are leaving yourself on the page, as much as the other person, is also vulnerability.

Something he says about the difference between knowledge, education and wisdom strikes me. “I could give statistics about the famine but it’s more interesting what is meant in the way I’ve handled it, and the questions you have wanted to ask.”

In this, we are both revealed.

Denise Chaila with President Michael D Higgins. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Denise Chaila with President Michael D Higgins. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.The Fifth Pillar

I’m not sure what I had been expecting. Maybe to be greeted by a courtly statesman and have a careful bureaucratic conversation where we danced diplomatically around incendiary topics so as not to wake sleeping dragons.

Let me be candid. I knew how I didn’t want to write this piece: “A rapper and the President of Ireland walk in to a pub – what happens next will shock you!” A gag. Uninteresting caricatures. No ma’am. But I knew what I was hoping for it to be. A meeting that perhaps would be as edifying as it is interesting. My intention entering this was to encounter a person; not a meme. And it was to be present as a person, not a single song.

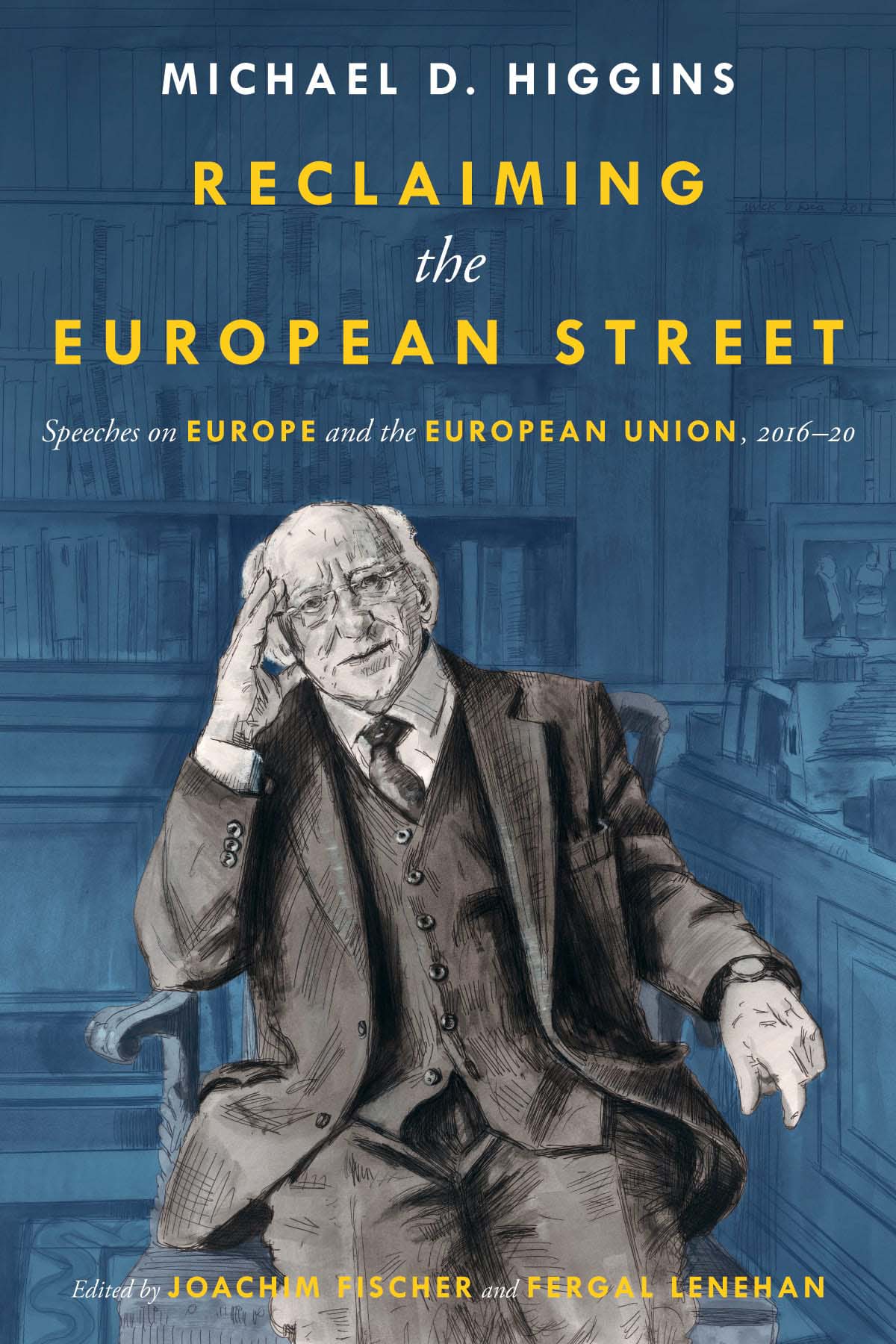

As I read President Higgins’ new book, Reclaiming The European Street, I was struck repeatedly by its urgency. By its passion. It is a book that wants to be accessed, not merely intellectualised. It is pressing, the language is simple and direct. This project began as a series of speeches and is intended to continue as conversations about who we are. What exactly must we claim back? What are we entitled to claim in the first place? As citizens? As Europeans?

I cannot pretend to have ever had to carry the level of responsibility for representation that he does, but it surprised me just how much common ground we share. Perhaps it shouldn’t have. Especially considering that over the last year I feel I have sometimes occupied a representative role for an idea of ‘black Irishness’ in ways that have felt deeply uncomfortable because these things are not monolithic. Claiming a mantle as a representative when you were not elected by a community to occupy it is... inadvisable at best.

All these things were on my mind as I had entered the Áras carrying a white and purple orchid in my hands, thinking about the day I was naturalised as an Irish citizen and how much has changed between then and now. Thinking about how few people in the communities I am part of, consisting of Irish people who are black or migrant, feel entitled to political engagement. How few of those feel as though their government truly serves them or sees them. How by giving myself permission to be a part of this place and this conversation, already I have reclaimed and healed something in my own psyche that constantly asks whether entrance and personal advocacy in these places is even permitted.

The day we spoke, I placed my phone on the table, put on my lo-fi, anti-anxiety playlist and wondered what titles to use to address him. I’m not in the habit of meeting presidents and wasn’t sure what ceremony to stand on. I forgot this anxiety quickly, because good conversations rarely give you time for self-consciousness. He asked me about doing English and Sociology and I sheepishly explained (as I usually do ) that I gained a lot from it and the Politics and International Relations one I did before it, but didn’t finish either of them.

“I have three unfinished PhDs because I kept coming back to politics,” he said with a half smile. “I actually was very far on in my one about migration but I came back to stand for the Labour Party. There was no one going to stand from the west of Ireland, so I stood in 1969.”

I ended up talking to him about the process of breaking out of the form of the academy. Of taking your discipline and running off the page with it to bring it to another audience. To breathe life into texts and live them, trial them, use them. We spoke about his life. His time in Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria.

“I went to a minefield and became an honorary Sahrawi in the dessert. My Sahrawi companions, they hadn’t had a white person do this. We would go to a non-drinking well and they would pour water over me as a way of keeping me safe.”

He took me through his time in Salvador and Chile, walking through favelas, in Turkey by the Black Sea attending a citizens trial, watching other migrants swap stories and photographs and forging bonds of trust. Breaking down the walls of the academy to have what he calls a ‘promiscuity of experience’.

“Lying there outside the tent, and looking up at the sky. The clearest view I’ve ever seen in my 80 year old life of all the stars because you’ve no pollution. I often say, I think that they were more important experiences for me than if I had locked myself in my study at university.”

My journey into Hip Hop is like this to me. A real attempt to smash the walls between the academy, the pragmatics of my life and my needs as a person. To claim the underpinning philosophy. At their collective heart, rappers are street philosophers. Sociologists, rogue poets engaging the world and transforming it by vulnerability or aspiration or confidence. Whatever you may think of their individual philosophies.

‘Knowledge’, few people know, is the fifth pillar of the five tenets that make up the cultural tradition of Hip Hop. This art began as an act of reclamation in itself, for a group of kids in the New York who divested from popular music to reclaim their streets, by creating music which centred their voices before they were heard.

Denise Chaila, Murli and God Knows with President Michael D Higgins. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Denise Chaila, Murli and God Knows with President Michael D Higgins. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.Real Community

In 2017, I would hop on hellishly long (but blessedly cheap) busses from the Netherlands, where I was studying at the time, to... basically anywhere I could in Europe. I remember feeling the weight of discussions of imperialism and nationalism I’d had in class truly start to take shape as real truths which impacted my body and psyche. Viscerally. It’s one thing to experience something you have no name for. It’s another entirely to know exactly what is happening and why, and find yourself unable to shake yourself from the nightmare of it..

Even then, funnily enough, I considered myself Irish, but never truly European until I got to Customs & Immigration at the airport. My subject position makes this entire topic very difficult to consider. It’s not an easy conversation by any means. Thinking about ‘Reclaiming the European Street’ is an exercise in radical and revolutionary ideals regarding the way I am received as a human being on the territory which is the throne of imperialism and colonial thought.

Here I am in an empire which has not truly addressed its historical implications in colonised nations, and how this affects trade, the economy and debt today. Adopted by a nation who have by turns been racialised and have achieved whiteness in a way that speaks to historical amnesia. Having my roots in the empires it ravaged. Asking what it means to be European.

“And this, I say in the book: one of the things which upset some of the diplomats, is when I said of the European Union, ‘You have managed to have an accommodation with your memory yourselves by assuming that everyone has forgotten [the facts]’.”

Africa has not forgotten, Latin America has not forgotten he stresses.

“Hannah Arendt – why did she not forgive Martin Heidegger, who had been both her teacher and her lover, but also had such [a] horrific collaboration with the fascist regime? She couldn’t get to begin the point of forgiveness with Martin Heidegger because he never would begin to acknowledge the fact of what had happened.”

Coming to a consensus about the historical facts in a way that umbilically connects us to truth, and not a safe or anodyne version of it, is the call at the very soul of this text. Refusing to accept that we cling to false narratives is shielding us from the necessary work of accepting truth. This prevents us from building real community and real relationships with one another and fragments us in every way. To think about the connections between these things, we must begin to remember Leopold with the same eye we remember the atrocities of Hitler. To think about the connections between these things. To think about what it says of the way we value human life that these connections aren’t made.

“Tut-tutting about racism isn’t enough,” he says, firm. “It has to be identified, opposed. And not just opposed, eliminated.”

And in doing so we create precedents for moral standards (ones which lead to action not more rhetoric), which pave the way for empathy, and community care. And community is what ultimately makes this worth it, what makes the journey bearable when cynicism or frustration or disappointment come knocking.

“The companionship of those who have been rattling the cage with me has been beautiful,” he says. “I’ve made great friendships. The only thing about it always was leaving the situation.

“Stalin and his ilk ruined it for the rest of us,” he adds casually. And I’m reminded of the Edward Said book beside my bed, the Adrienne Marie Brown quotes in my journal, the gallery of decolonisation and socialism I have curated my Instagram feed to be in the last year.

We discuss the grace of Leonard Cohen’s performances, he quotes me Sinéad O’Connor and gives me Emma Dabiri’s book What White People Can Do Next: From Allyship to Coalition. He tells me how he referred to it while writing a speech about the famine. We discuss the book How the Irish Became White by Noel Ignatiev. We build bridges.

We discuss the demonisation of certain kinds of music in Ireland— fiddle music as “the Devil’s music” and how the church forbade the playing of Jazz on the grounds it was “low African rhythms.” ‘No blacks, no dogs, no Irish again,’ I think to myself.

“What we’re dealing with is a long, unaddressed history of inequalities accepted and defined as culture. And prejudices and exclusions that were allowed,” he finishes my thought without knowing that he does. The bulk of my own work has been this. Returning to history and discovering what has been lost, omitted or discarded in order to support this notion that a cultural identity is something which is not only in stasis; it is in direct opposition to the rest of the world. It is not enough that it is good, it must be better. In order for it to be better, something must be worse. In order for something to be worse we must create an Other. And our gaze is not directed where it ought to be: towards misogyny, white supremacy and imperialism, classism, ableism, homophobia or any number of things.

It is directed at the foreigner. The migrant and nomadic. Often because they are unable to speak back and define their own narratives. This is the path of least resistance. This is also the path of identity crisis. Of this nationalism the President says: “It’s something that people haven’t faced up to. What a very thin, weak, light egalitarianism was within Irish nationalism. Be it in relation to the poorest, be it in relation to women, be it in relation to those who didn’t obey the law.”

Denise Chaila. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Denise Chaila. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.No One Should Inflict Humiliation

Sitting in a room surrounded by the portraits of his predecessors, I found myself grateful that it was President Higgins I encountered. That I had found myself before a poet, a philosopher, an intellectual who seemed more concerned with finding ways for us to speak truth with each other than with ‘doing an interview’.

“I have to tell you, Denise, people aren’t so comfortable hearing this from me” – he is opening a bottle of Ballygowan for me because I can’t manage it, for the life of me, while having a conversation like this. “They say, ‘that’s the kind of thing Michael D goes on with’ but this I have to do.”

And it seems counterintuitive. How do meditations about the famine converse with a discussion about Black Lives Matter and Trans Liberty? What is the common denominator here between the freedom of Palestine, unification with the North, class, ableism and environmental justice?

In the end it is simply that these things are not and have never been as brutally divorced from each other as we would like to make it seem. I might discuss this as intersectionality. Some call it egalitarianism. What we are all saying, very simply, is that to commit to fighting one injustice you are committing to fighting them all.

“You cannot be a tourist of the revolution,” President Michael D. Higgins says. “You cannot be a tourist of any of these issues. I keep saying to people you can’t cop out. You have to push yourself towards understanding. I say about the famine, for example, there’s no point in saying that this is something we shared as an experience, we didn’t share it as an experience. It was imposed. It was avoidable. It was the outcome of a set of assumptions and of assumptions about superiority, one people over another.”

It is impossible to pick and choose an issue. If we do, we will forever be treading water, failing to understand that attacking random tentacles does nothing but enrage the Kraken further without striking a killing blow. We must choose holistic integrity. We must choose justice as the pursuit of pleasure, dignity and actualisation for all within our communities. Here – within these communities – we answer who we are, why we operate in the ways we do, and who it ultimately serves: these are what draw us closer to truly reclaiming elements of our humanity that we have lost to capitalism and the idolisation of our bottom line. In President Higgins’ words, “We’ve paid a very high price for artificial hierarchies, patriarchy, and insensitivity.”

And reclamation goes much further than conferences, task forces, empty promises to ‘do the work’, diversity quotas or being woke. It begins with personal challenges that penetrate and permanently alter the way we live. It goes further than using the word ‘hope’ as an empty placebo where the word ‘justice’, ‘structure’ or ‘organisation’ should be.

“You have to do much more than just starting to count people. Saying ‘we have so many men, so many women, so many people of colour’. You are stopping very far short of co-existence. If you begin at the other end and say for example ‘we all realise that something has to happen in relation to planetary change’ – something has to happen, in fact, in relation to the way we’re managing our connection between the market and society. And the fact that we’re sharing these projects means we can call ourselves what we like. You can say ‘I’m a hip hop person’ now and change in the next ten minutes. That’s where it has to go.”

However, to do this we must come to mutual understandings about who we actually are as people, as citizens, as individuals. What this means for us as a community, as a city or as a nation.

“I did a meditation on home. I did a more recent one on humiliation. I was in Palestine and it was yet another ineffectual visit. I had been meeting NGOs and it was about the time of the wall [on the West Bank, which Palestinians call the ‘apartheid wall’] and I saw things. I saw, for example, a young Israeli soldier. And I saw a very old Palestinian woman standing there with her bag of vegetables. And he takes her papers and he disappears for two or three hours. Her stuff is perishing and all of this and – this is all humiliating. I was talking to somebody afterwards and I looked at a study on trauma that showed that in relation to children, they actually suffered more from witnessing their parents being humiliated than they did from the death of either parent. To me, in my life, in a way I know what that was like because there were circumstances, where I saw that. What is there to compromise about in the end? Nobody should inflict humiliation on any person ever. And also, respect involves work.”

Denise Chaila with President Michael D Higgins. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Denise Chaila with President Michael D Higgins. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.Make Peace With The Truth

This work is difficult. Nothing is done without risk. No truth is spoken without acute awareness that speaking leaves you vulnerable to embarrassment, mockery, abuse, threat, and even the loss of certain freedoms. And yet, this is the point. Somehow, while meeting opposition, we throw a spotlight on discussions and ideas which harbour demons whose names we must speak aloud to exorcise.

I am reminded of Kwame Ture.

“I knew that I could vote,” he said, “and that that wasn’t a privilege; it was my right. Every time I tried I was shot, killed or jailed, beaten or economically deprived.” This is a knowledge we must embrace. An understanding that when the law of conscience is in conflict with the law of government, we have tools and methods through which we may protect each other. Fearlessly even. According to that higher law, by knowing our rights and our responsibilities within the systems we already exist in.

Before policy, beyond policy, we are a polity. A nation, a city. Comprised of many lives, dreams, wounds. And all of us in this polity, in this city, are political. Everything you do and the way you behave is political. Therefore everything you dream and every way you try, always matters.

A community of vulnerabilities recognised.

And we were vulnerable. The kind of vulnerable that comes with real truth telling. That comes with telling our respective stories.

“I was born in Limerick,” he told me. And I smiled, because though I only discovered this recently enough, my friends had known. Limerick had absolutely not forgotten, and I had come to him with messages and gifts from people who wanted to send him the work of their hands, their blessings, their love. CDs, shirts, a photo book, vinyls, chapbooks, a letter from a seven year old called Charlie, and a lot of good will.

“I left Limerick when I was five. See this was my life. My father’s health broke down. I was born in very comfortable circumstances briefly on the Ennis Road. And then my father’s business begins to fail, and then he’s drinking and then his health is breaking down. My elder twin sisters are a year and a half older than me, my brother is a year younger than me. So you have four children under six years of age. And then you have an aunt and they’re in County Clare in Newmarket-on-Fergus, and we were meant to go out on the farm temporarily.”

But it wasn’t temporary. He describes a personal migration story full of grief and compassion that echoes stories I hold inside me too. I say to him it must be difficult to hold space to acknowledge that you hold multitudes (fire, tears, rage, great joy) when it seems people only ever wish to receive you at your most benign. I’m received with the empathy of someone who has lived this reality much longer than I have.

“If you only knew! All these images and tea cosies and things like that. And if they want to do that, that’s fine but actually, I have great lonelinesses in myself.”

His words resonate with me. I’m sure to some extent they do with all of us. Without exception, this year has been the hardest I’ve ever lived through, privately or publicly. This is a shockingly difficult thing to say. It’s hard to accept that in a world which has waltzed with my dreams for the better part of a year, my heart is often so burdened with weight it can be difficult to live in moments of joy. And yet, if I do not call out the tension and sit with it here I would be a liar.

This has been difficult. To grapple with a new public identity in quarantine has been difficult. To live with the tension and joy of a completely transformed life while nursing the grief of losing freedom, and watching family members buried over Zoom calls (plural) is hard. Occupying a space where the unequal dissemination of vaccines to ‘developing countries’ is an economic debate in the west, but directly affects whether people I love receive life-saving care, is a nightmare.

And I’m certain that I will have to remain vulnerable within these wounds and make peace with the truth that the story of my life and my dreams will not be what I thought it would be. And this is ok. This is also revolution. Not to destroy, but to create anew. To build and rebuild with integrity. Because while not fluffy or sweet or easy, it is meaningful and real and there is time to heal and rest.

“I only wish I had several decades more,” he speaks evenly, clear eyed. “In a curious way I’m actually moving into the more concentrated, succinct, part of my work between philosophy, which I’ve returned to, and social theory, and economics.”

Speaking of Hope

Even as I reflect on the conversation we had, I am conscious of how much space has been created within me for more hope. For real hope. Hope that relies on people like this continuing to be fearless and hold space for us to work this out together.

“As long as you’re still curious there are possibilities,” he says as we speak of grief, of depression, and ultimately of hope. “And all the possibilities can be shared.”

I believe him.

• Reclaiming the European Street: Speeches on Europe and the European Union 2016-2020 by Michael D. Higgins is published by The Lilliput Press.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 02 Mar 26

'No War On Iran' protest to take place in Dublin this evening

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 23 Feb 26

Online and side-line abuse: "Nobody is safe. The monster never sleeps"

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 22 Feb 26

Manchester Disunited: Toxic, far-right rhetoric needs to be condemned in the strongest manner possible

RELATED

- Opinion

- 26 Jan 26

Education Special: Expand your horizons through these creative courses

- Opinion

- 26 Jan 26