- Opinion

- 08 Nov 21

All Against Racism: That Has To Be Our Ambition

It is just over 100 years since Ireland established its independence from the UK. Sadly, the ideals of the Irish revolutionary period were badly betrayed in the way the State subsequently evolved. But over the past 30 years, extraordinary advances have been made, which offer the possibility that Ireland might yet become a world leader in promoting human rights and equality, and in eliminating racism. As our 100 Voices Special confirms, there is no better time to start than now...

It is just over 100 years since the establishment of the Irish Free State. It was a complicated moment in Irish history, in which decisions were taken that would have an enormous and horribly lasting impact on Ireland – and on what it means to be Irish.

The decision, taken by Michael Collins and his fellow negotiators from the Irish Republican Brotherhood – of which Collins was President – to sign the Treaty with the British that would end the War of Independence, and to accept the partition of the island of Ireland, plunged the country into what was a particularly gut-wrenching form of civil war, which pitched brother against brother and tore families apart. The Sinn Féin party split down the middle. So did the old IRB. Former comrades in the struggle to defeat the British forces took up arms against one another. It was bitter and bloody, with thousands dying. Just about no one came out of it well.

With the benefit of hindsight, those who signed the Treaty might have acted differently. Certainly, they would not have willingly chosen the bloodshed and mayhem that erupted; the personal vendettas which saw many of the leaders of the Republican movement murdered or executed; and the deep-seated enmities which would define Ireland’s political culture for generations to come.

Undeniably, the outcome was, in very many ways, a betrayal of the spirit of the independence struggle, which had been building momentum through the previous decades in Ireland. It wasn’t just that it enabled the creation of a corrupt, sectarian, apartheid-style regime in the six counties of Northern Ireland, the control of which was left to the British government. What happened south of the border was no exemplar either. Far from it.

In the Free State, women were quickly shunted off the political stage. The pro-Treaty wing of Sinn Féin became Cumann na nGaedhal, and later Fine Gael; they retreated from any form of radicalism, willingly conspiring in the creation of a depressingly insular, confessional State in the south.

Gradually, the influence of the Vatican seeped into every pore, turning Ireland into a deeply conservative, fundamentally theocratic, sectarian State in which women were effectively debarred from public life and Roman Catholicism became, more or less, the only religion. Anti-semitism was rife. Outside influences – other than those emanating from the cloistered, male-only whispering rooms of Rome – were treated with suspicion if not downright hostility.

In fairness, we were dealing with a corkscrew post-colonial legacy. During the economic war in the 1930s, the Brits turned that screw. Whatever attitude we might have taken to the Nazis, as Hitler’s demented mob flexed their muscles ever more ominously through that decade, was complicated messily by the fact that we had been in open conflict with the UK government.

We avoided the sinister embrace of fascism. But the risk was real that, if the winds had blown in a a slightly different direction, the Catholic hierarchy, in Rome and in Ireland, might have more than willingly facilitated a link-up between the Irish Blueshirts and the fascist Catholic dictatorships that seized power in Italy, Spain and Portugal. There were dangerous, anti-democratic forces at work right across Europe.

We escaped the noose they were fashioning and – for better or worse – stayed out of World War II. What emerged in the aftermath of that immeasurable, man-made catastrophe, here in Ireland, was a hopelessly small-minded, and bitterly parochial sense of what it meant to be Irish. We were, for the most part, a white, male-dominated, religion-obsessed, self-consciously pious, repressed, suspicious, shame-filled, and in many ways poverty-stricken people, incapable it seemed of building a society that could provide for its seed, breed and progeny. It was of necessity that we were a nation of emigrants. And yet, we bullied and beat our children. Women were treated like dirt. We watched the population dwindling.

My parents taught me to be proud of being Irish. In truth, there wasn’t a lot to be proud of.

Seán Lemass

Seán LemassThere are those now, who want to return to that blinkered sense of narrow, deferential isolationism. Who believe that there really was a viable version of what it might mean to be Irish forged in that putrid cultural wasteland of toxic authoritarianism. Well, fuck ‘em.

Anyone sane would look back at that world and ask: how did we screw things up so royally? How was it that the ideals of the Republic had been so utterly twisted out of shape during the ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s? How could women – having played their part in the independence movement – have been so brutally and successfully excluded from positions of power and influence in Irish life? And why were the people of Ireland so willing, for so long, to turn a blind eye to abuse – and to live in a state of miserable, paranoid fear, about what might happen if we engaged properly with progressive, rational forces in the outside world?

Much of this toxic, guilt-riddled culture can, of course, be put down to the pervasive and deeply insidious influence of the Roman Catholic Church. The political regime here, forged under yoke of Rome, was a pernicious one. Irish politics, especially at local government level, was an arena for far too many gombeen men and hucksters, who waltzed into the proverbial parlour, with cries of “Ya boy ya” ringing in their ears and brown envelopes loaded with corrupt payments sticking out of their arse pockets.

But the grid was shifting. And gradually, the feeling crystallised: that something really must be done. That Ireland would have to move on – politically, morally, philosophically, economically and in terms of sexual freedom. That there was potentially a better life to be led, if only we could muster the courage to go there.

The old shibboleths had to be cast aside. It dawned on us, or enough of us at least, that Irish society could be liberated from the covert machinations of the hierarchy; from the ignorance and absurdity of censorship; from homophobia; and from the insidious oppression of women. It dawned on us, too, that our creative energies might finally be channelled into achieving things. And that if we properly asserted the right to stand tall on our own behalf, then the world would be far more likely to listen.

As Taoiseach, during the 1960s, the Fianna Fáil leader Séan Lemass had abandoned the policy of protectionism. The world around us was changing. Technology was opening things up. On the radio, Irish people tuned in to AFN, Radio Caroline and Radio Luxembourg, as well as BBC. With the arrival of RTÉ television, UK TV channels became much more widely available here.

It was only a matter of time before the citizens of Ireland would begin to realise that the great, big, beautiful world out there was far more diverse, colourful, interesting and stimulating than the self-styled island of saints and scholars. And so it proved.

In 1972, 83% of those who voted embraced the new when Ireland chose, in a Referendum, to join what was then called the EEC (European Economic Community). Just about no one knew how profound the impact of that decision would be. In becoming part of Europe we also bought into its growing commitment to freedom of movement, to human rights, to women’s right to reproductive integrity and to a variety of positive and empowering environmental and social principles.

The Irish government had effectively signed the death knell of the old authoritarianism here. It didn’t mean that we now had abundant reasons to feel proud to be Irish. But we had, at least, taken a significant step in that direction.

Later, our membership of the EU meant that we would happily open our doors to people from all over Europe, who – anytime of the day, week, month or year – could come here to learn, live and work, and be treated as equals.

The effect in the 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland was profound. Gradually, what had been a relatively poor, mono-cultural place was transformed. Economic output has since exploded. Similarly, from a low of 2.8 million in 1961, the population of the Republic has increased to over 5 million in 2021 – and rising.

It hasn’t always been one-way traffic. Government policies in relation to housing, addressing disadvantage and alleviating poverty have often been woefully inadequate. We hit a major iceberg when the banks collapsed. There is undoubtedly an argument that the EU can be blamed for the socialisation of private debt that occurred then, as Governments scrambled to keep banks open and the political show on the road – and ordinary citizens suffered disproportionately.

But, however you mince it, the underlying reality is that Ireland has been one of the top performing economies in the world over the past 20 years and more. Broadly speaking, we are in a much better place than at any time previously in our history.

In 1990, we elected our first female President and all over Europe they stood back and applauded. Then we elected our second. In music, literature and film, strictly on merit, Ireland has claimed it place among the great nations of the world, emphasised by the global success of U2, Enya, Sinéad O’Connor, Bill Whelan’s Riverdance, The Cranberries, The Script and Hozier, among many more.

In sport, we delivered to an extent we’d never even imagined possible – in football, rugby, boxing and later cricket, rowing and hockey. In science and technology we made undreamt of strides. It would be entirely wrong to suggest that we were, or are, ar mhuin na muiche. But we have got a lot of things right – and the other bits can be fixed if we have the collective determination.

On the ground, meanwhile, a subtle transformation was taking place.

From all over Europe, new citizens were arriving here. Gradually, the complexion, and the identity, of people on the streets of Dublin and of Ireland were changing. Children of the Windrush generation were coming in from the UK. From France, second generation North Africans were joining us in the big cities, or wherever multi-nationals headquartered themselves.

A new breed of educational entrepreneurs began to see the potential in teaching English to students from all over the world. There was a particularly strong take-up from Brazil. That ushered in a new phase. Many of those born in Brazil are entitled to passports from Italy, Portugal, Germany and elsewhere in Europe. Many of them have become European citizens and can stay indefinitely in Ireland. And they have done just that. It is one of the great, quiet revolutions.

The new Irish have come too from different parts of Eastern Europe, notably from Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Romania. They have also arrived from Nigeria, Libya and other countries in Africa. Four of the 2021 Hot Press Munchengladbach squad are from Mexico. Current estimates say that approximately 17% of the population of Ireland are from a non-Irish background.

Our horizons are expanding. Our streets are becoming more colourful. Our music is becoming broader and more inclusive. There is a feeling of energy and excitement about the place. We are on a roll...

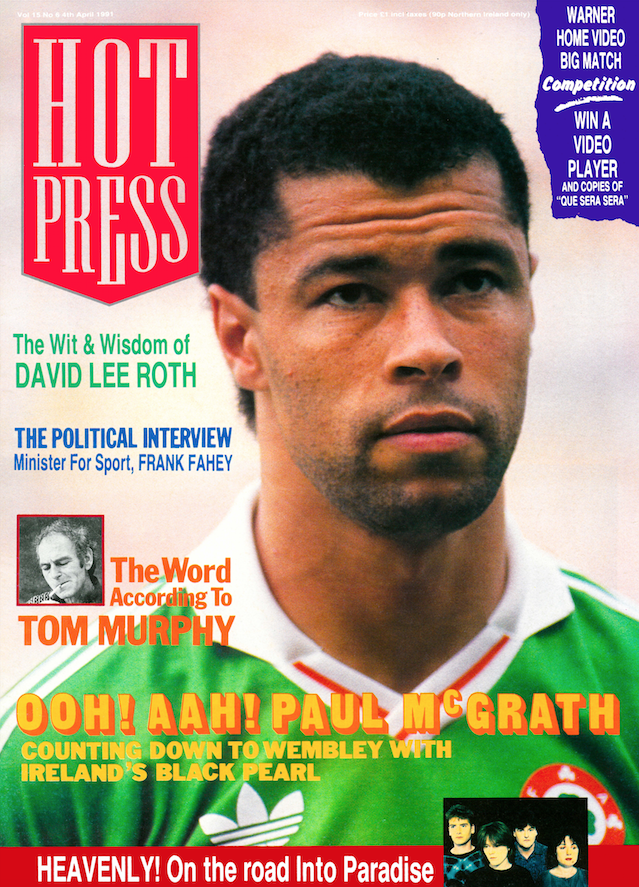

So how are we treating the new Irish? We always imagined ourselves open and generous – as Ireland of the thousand welcomes. But does the cap fit? Historically, we could point to the fact that Philip Lynott and Paul McGrath became national heroes, that they were embraced and loved by people all over the country.

That’s true, but it only tells us so much. It was easy to behave openly when the numbers of Black Irish people were tiny. Can we now do the same thing, as circumstances change and the numbers grow? How do those people who might be considered new to these shores feel about the way in which Irish society meets, greets and treats them? Is there a difference between the way we respond to Eastern Europeans, Africans, Brazilians or people from China or other Asian countries? And where do our own best known ethnic minority, Travellers, fit into all of this? And what about the baneful impact of social media, where mobs can be stirred so easily to hate?

These were just some of the questions that we wanted to explore when we joined forces with the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission, to work on the #AllAgainstRacism campaign.

We do know first-hand that there is racism in Ireland. I am still mad enough to go out every Saturday, to play in the legendary purple of Hot Press Munchengladbach. Our squad is a powerfully multi-cultural one, more so than any other side we play against in the AUL. There are, we have learned, tens of thousands of footballers actively involved in the game who couldn’t care less where the players they are lining-up against come from, or how the colour of their skin might be characterised.

Then there are the others. Small in number, for sure, but all the more vocal for that. Our players – from Mexico, Portugal, Nigeria, Brazil, Tunisia and elsewhere across the continents – have experienced numerous instances of racism. I have written about it before in these pages and so I won’t plough through the details again. But the current season is no different from last year or the year before that.

Racism, when it happens, is most overtly directed at our black players. But not exclusively. Badly bruised in a reckless, late challenge, our Brazilian goalkeeper appealed to the referee for protection. “I have to work tomorrow,” he said. “Yeah, for Deliveroo,” one of the opposition said with a snigger. Against a more volatile collective than ours, an incident like this – which left our man black and blue for a week – could easily have escalated into something very ugly.

Having been through that sort of provocation, it has been fascinating to talk to people and to read the various contributions for our 100 Voices Special, as they winged their way in, from people all over Ireland, including Northern Ireland.

A few things became evident. There seems to be an element of fatigue among some black artists, who feel that they made a statement around the Black Lives Matter protests and that they now want to move on. There is also an element of caution. Some artists and sports people told us that they hadn’t experienced racism – or not in what they considered a meaningful way at least – but that they didn’t want to risk undermining the testimonies of those who did.

Others acknowledged that there is a fear of social media and the poisonous way in which sustained attacks are mounted against individuals, whether on Twitter or Facebook, by the still small but now more organised knuckle-dragging right-wing generally ‘nationalist’ racists who are active online. And in that context, some artists and sports people alike, expressed a concern about their own mental health, even, in some cases, preferring to remain out of the picture in order to stay as free as possible from anxiety attacks or depression brought on by social media assaults.

Alicia Raye

Alicia RayeWhat emerges in 100 Voices: All Against Racism, in spite of these concerns, is hugely revealing, but also encouraging. The voices of those who have experienced racism need to be heard. This is especially so in relation to those who have come through the Direct Provision system, and who have therefore felt the brunt of institutionalised racism to the greatest extent. Their anger is understandable, as we will read again in a lengthier contribution from Alicia Raye in the next issue of Hot Press.

But there are other, more positive twists to this story and how the narrative is being re-shaped. First, there is the evident solidarity, and mutual respect, which is expressed over and over again, by so many of the artists and activists we spoke to, across all musical, cultural and socio-economic groupings. We could have filled an entire issue of Hot Press with the words of musicians of Irish origin, welcoming their multi-cultural brothers and sisters to the local musical playground. That is wonderful to see.

It is also notable that this spirit of inclusiveness extends to the Traveller community, who are identified by a number of contributors as being the original – and sometimes the primary – target of racism in Ireland.

Finally, there is the recognition, expressed by a number of the contributors, that – compared to places like Hungary, Poland and even the UK – Ireland seems to be heading decisively in the right direction. And there is the belief, expressed by some, that this country can potentially become a world leader in advancing the cause of human rights and equality, and in eliminating racism.

That has to be the ambition. And there is no better time to start than now. But first, we need to agree on a definition of what it means to be Irish – one, hopefully, that we can all genuinely be proud of.

#AllAgainstRacism. That’s the one. And it can be done...

The 100 Voices: #AllAgainstRacism special issue of Hot Press is out now – and available to order online below: