- Opinion

- 12 Aug 21

Amnesty for Those Guilty of Appalling Crimes During the Troubles is an Insult to Families of Victims

There was widespread anger North and South of the border in recent weeks, when the British government announced that it was planning to introduce what the UK Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, termed a Troubles Amnesty. It wasn’t only the families of victims of violence at the hands of the British Army who protested. Victims of loyalist and republican violence were equally dismayed…

An amnesty, implicitly, sounds like a good thing. But, of course, it is not always so. And especially when the UK Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, is involved. So let’s step back for a minute and consider the context.

A rude awakening awaits anyone who thinks the Good Friday Agreement is ancient history. The 100th and 50th anniversaries of various national events that helped to shape the modern Irish state are coming thick and fast. What does that tell you?

Yes, they are of the past and yes, indeed, we shouldn’t live in the past. But neither should we forget that time and distance lend perspective and greater clarity. We could do with a bit more of that right now.

Approached in the right enquiring spirit, the past lays bare the present and, in that way, helps to shape the future.

What has been done cannot be undone. We all know that. But getting behind the myths to understand the reality of what the main players did, and why, might just allow us to address the challenges that we face now, and into the future, more effectively.

Those who forget to remember – or who remember selectively – condemn us to an endless cycle of evasion and irresolution.

INNOCENT CIVILIANS BUTCHERED

Which may well be the legacy of the British Government’s proposed Troubles Amnesty – if it gets the go ahead. The proposed mechanism is a Statute of Limitations. Its introduction would end any potential involvement of the courts in all Troubles-related activity, including criminal offences, civil actions and inquests alike. It would extend equally to security forces and to paramilitaries.

To be clear about it, this is what the UK government intends.

The Tories want to pack up the Troubles in an old kit-bag and smile, smile, smile. Pop the lot into the archive boxes and let historians unpack them page by page, whenever they get around to it.

But, of course, there is more to it than that, with Boris Johnson, as ever, playing to the gallery of chauvinistic knaves in the right-wing Tory press. He craves the applause that will follow any decision which will ensure that British army soldiers remain above the law, no matter how murderous, prejudiced and belligerent their actions might have been. But he is also protecting the politicians who knew about, and who approved – either officially or otherwise – the shoot to kill policy on which the army embarked.

In short, this amnesty is a further establishment cover-up by any other name.

Meanwhile, fresh milestones are coming into view on this island. Immediately, there’s the anniversary of Operation Demetrius in Northern Ireland. Better known as internment, it began early on Monday 9 August 1971 and continued, incredible as it now seems, until December 1975.

Only a handful of those interned during Demetrius were senior IRA members. Most were political opponents of the Unionists, members of People’s Democracy and the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, trade unionists and, inevitably, individuals who were victims of mistaken identity.

The British Army’s 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment waged war on civilians in the Springfield Road area of Belfast during Operation Demetrius, killing ten. It’s known as the Ballymurphy Massacre and it was an outrage on a scale that is hard to compute at this distance. But then, that’s true of so much of what happened in Northern Ireland, during the Troubles.

In 2021, the coroner’s report found definitively that all of those killed in the massacre were innocent – and that the killings were “without justification”. This atrocity was carried out by the British Army, in Belfast – which is claimed to be part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. And it was whitewashed for 50 years, in a way that never could have, or would have, happened if the same events had taken place in Manchester, Glasgow, Newcastle or London. The current British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, subsequently apologised for the deaths in a phone call to the then First Minister in Northern Ireland, Arlene Foster, and the Deputy First Minister Michelle O’Neill.

But there was no public apology.

December 4th 2021 will be the 50th anniversary of the bombing of McGurk’s Bar in Belfast by the UVF. Fifteen people, including two children, were killed and seventeen injured, the highest death toll from a single incident in the North’s biggest city during The Troubles.

It was monstrous in itself. But what made it immeasurably worse was that the security forces said it was caused by an IRA bomb that had exploded prematurely.

It wasn’t. And they knew it. This was disinformation. In the same way that the innocent civilians butchered in Ballymurphy were besmirched entirely in the wrong by accusations that they were carrying weapons at the time, the RUC and the British Army diverted the attention of the world and misled everyone by pointing the finger of blame at the IRA.

THE NARRATIVE MUST EVOLVE

In this instance, truth did eventually out. In 1977, UVF member Robert Campbell was sentenced to life imprisonment for his part in the bombing. He served fifteen years.

Six weeks later, on Bloody Sunday, 29th January 1972, the 1st Parachute regiment continued where they had left off in Ballymurphy and shot 26 unarmed civilians in Derry, killing fourteen. Scenes from that brutal, bloody day are etched forever into the psyche of those who were old enough to understand what had taken place. Thomas Kinsella wrote the epic ‘Butcher’s Dozen’ in response. In a poem that is well worth reading in full, he imagines the ghosts of those that were murdered stepping forward to give their accounts of what happened.

… A phantom said:

“Here lies one who breathed his last

Firmly reminded of the past.

A trooper did it, on one knee,

In tones of brute authority.

That harsher spirit, who before

Had flushed with anger, spoke once more:

“Simple lessons cut most deep.

This lesson in our hearts we keep:

Persuasion, protest, arguments,

The milder forms of violence,

Earn nothing but polite neglect.

England, the way to your respect

Is via murderous force, it seems;

You push us to your own extremes.”

At that time, in places all across the Northern counties, the people on one side of a historically divided community felt it was facing an existential threat. And they were: the vast resources of the British state had been mobilised against them. The objective was to shore up Unionist dominance. But at local level, in any conflict, existential threats abound; and, in the heel of the hunt, atrocities are committed by all sides.

So, did those atrocities justify massacres at the Abercorn Hotel, the Enniskillen cenotaph, Warrington, Birmingham or in the centre of Omagh? There is only one possible answer. NO.

Did the Reavey and O’Dowd murders In January 1976, warrant the Kingsmill massacre of eleven Protestant workers by Republicans? NO!

The list is very long and if I tried to get through it, we’d be here till the middle of next year. Tit for tat, tat for tit: that’s how it went for decades. Reading the reports again now, despair, anger and recrimination rise again, as they did before.

These were no innocents, the men and women – they were, of course, mainly men – who ran those sordid terror campaigns. But a lot of innocents died or were injured or threatened. And that’s where memory matters and why we can’t forget to remember.

Many of the innocent still await answers. Vows of silence serve the powerful. In some communities, and that term includes regular and irregular armies, people forget to remember because the culture continually reminds them to remember to forget.

In his contributions to the decade of commemorations President Michael D Higgins has repeatedly stressed the importance of two necessary courtesies.

Firstly, we must include and recognise the voices that were marginalised, disenfranchised or excluded as the grand narratives were being written. Secondly, we must be open to the perspectives, stories, memories and pains of the stranger.

Who chooses what should be remembered? Or forgotten? Or forgiven?

What is memory? How is it constructed and how does it work?

We know it’s fallible, to say the least. Indeed, as Oliver Sacks tells it in his wonderful valedictory collection The River Of Consciousness, we are continuously editing and ordering our memories, often unconsciously or even sub-consciously. We make them fit the story we want to tell.

Nobody, ever or anywhere, has perfect recall. When it comes to the grand narratives the best we can hope for is broad consensus. But even here the risks of an abuse of power; of group-think; and of exclusiveness are vast. Look at Catholic Ireland in the 20th century. Look at Eastern Europe today.

We tell ourselves stories to cement our common identity, our bonds with one another and with where we live: that is, with our place and our people.

But peoples disperse. The Irish certainly did. Others may take their place. This is entirely normal and healthy. So, the narrative must evolve.

In telling ourselves these stories we want to be accurate, of course; but there is a pressure also to be ‘faithful’. Faithful, that is, to our place and our people and therefore to the shared narrative.

All too easily, however, this impulse to be faithful can ossify discourse, and poison politics and culture alike. In turn, those who question the sacred cows are othered, seen as apostates, as traitors…

WE REMEMBER TOM OLIVER

And so it goes. Where it started no one knows. But the outcome is, in most cases, the same. The powerful, the dominant, are always advantaged in shaping the grand narratives.

This is a moment to stop and think. When we mention power, we think immediately of the wealthy, the educated; of oligarchs, rulers, mandarins and clerics.

In so doing, we often forget those with other, no less dangerous, powers: the ones with weapons and mobs at their disposal; with armies of bots; with virtual battalions, ready to do the masters’ bidding. There is covert power too: the quiet persistence of class, codes, faiths, implicit understandings, whispers, the things that need not be said because everybody who is on one side of the argument – or of history – understands…

So this is not the time for what the British government calls “moving on”. The wounds were, and still are, too deep. And the rank injustices – perpetrated by all of the factions that were involved in killing people in the North – were, and still are, too foul for us simply to forget.

Rather, we must continue to search. To uncover, literally where the bodies of the disappeared are concerned, what lies beneath the surface. To keep challenging what has been said and, of equal importance, what has not been said. Because we need to know the truth, as far as it can be divined.

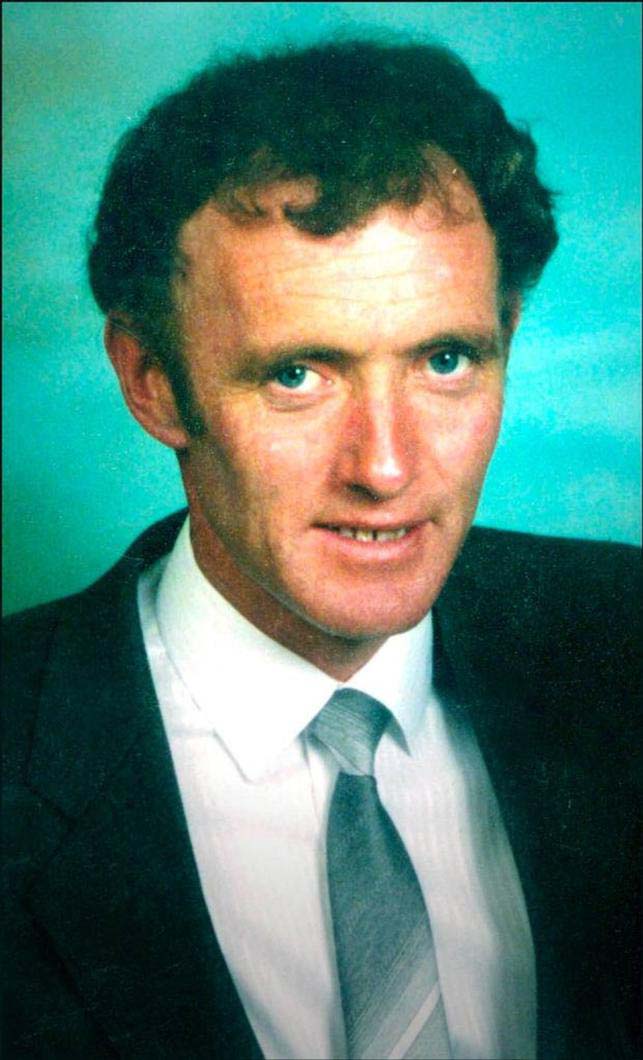

So, we remember Tom Oliver, a quiet farmer from Cooley who was abducted, tortured and murdered by the IRA, thirty years ago this summer. That might seem like a long time. But it isn’t.

Tom Oliver

Tom OliverHis family want to know the truth about that shocking and shameful crime. And they have a right to know. If possible, they want those involved in committing the crime to be prosecuted. They have a right to that too.

They speculate that sufficient time has elapsed and that it might now be possible for those with knowledge of what happened to come forward. And, of course, there are people out there who do know. Many of those with first-hand knowledge are in Sinn Féin. Some of them may even be in positions of prominence in the party.

The Oliver family’s solicitor, Darragh Mackin had this to say: “Tom’s case is the prime example on why there can be no limitation in time for investigating a murder. The family’s grief has no limitation, and neither can truth, justice, or accountability.”

Does anyone in the British government disagree with that? Or in Sinn Fein? Perhaps they do.

What Daragh Mackin says applies to all of those who died or were injured during the Troubles; and it applies especially to the ones who never carried a gun, who never set out to hurt or maim, who were innocents, sucked into a brutal and murderous conflict that was not in any way of their making.

Rather than close the book with a statute of limitations there should be a renewed push to reveal the truth while memories are intact, even if no prosecutions are realised.

Look at how far back we reach with mothers and babies and clerical abuse. That was the right thing to do: to drag the past out into the light, in a way that enables us all to understand just how badly ordinary people were abused by those in authority.

And so, no matter how much it suits those who want secrets to stay buried, we must not allow it. We know from the Mothers and Babies homes that we can’t credibly claim that it is okay to forget to remember.

A decision to pack up the Troubles in an old kit bag and smile, smile, smile, smile is a case in point. It says that, as far as the Government of Boris Johnson are concerned, these people don’t matter.

But they do.

RELATED

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 27 Jan 22

The Whole Hog: The 10 Big Issues We’ll Wrestle With In 2022

- Opinion

- 30 Nov 21

10 Things I Really Want For Christmas This Year

RELATED

- Opinion

- 22 Feb 21

Covid-19: England to begin easing lockdown in two weeks

- Opinion

- 13 Jan 21

The Hog: Climate Change – The End Really Is Nigh

- Opinion

- 24 Dec 20

The Eu And The UK Agree Brexit Trade Deal

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 22 Dec 20