- Opinion

- 04 Jan 24

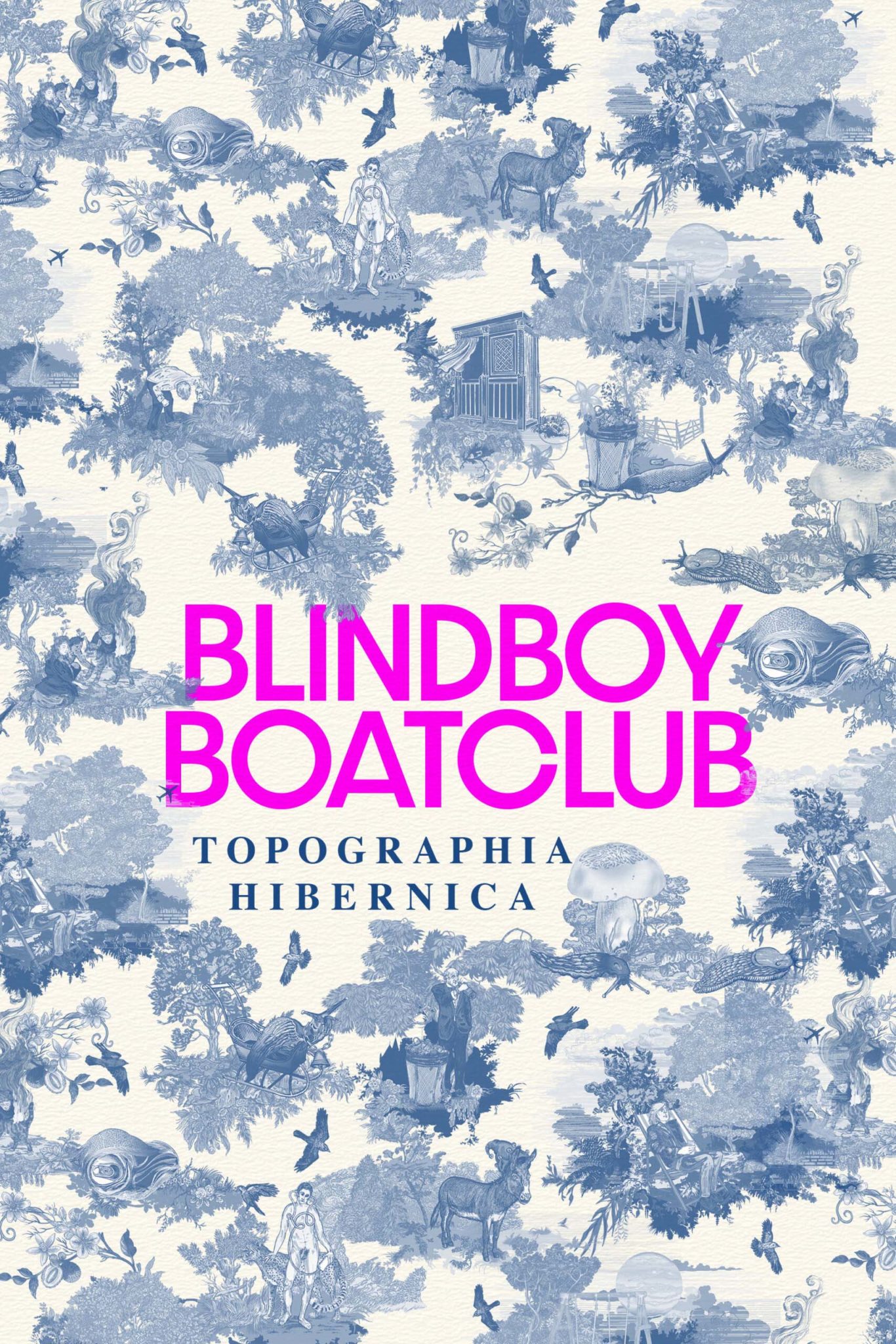

Blindboy: "There’s a childhood curiosity that we’re all born with, and that never left me"

Podcaster, author and all-round cultural phenomenon Blindboy is back with his third book, Topographia Hibernica. He catches up with Jess Murray to discuss Flann O’Brien, Gaza, Cypress Hill, colonialism, neurodivergence, and their beloved hometown of Limerick City.

My first introduction to the work of Blindboy was over 20 years ago, in the infancy of the Rubberbandits. At this point, the plastic bags and indeed their faces were unknown, but everyone my age in Limerick had a burnt CD-R of hilarious prank phone-calls made by the duo.

Since then, Blindboy has gone on to become a best-selling author and internationally renowned podcaster, with over a million worldwide monthly listeners.

His third book Topographia Hibernica is a brilliant collection of wild short stories, showcasing his unique brand of dark humour and his vibrant creativity.

“It was really tough writing it, because I got a bad auld dose of writer’s block over the whole lockdown period,” he says. “When you’re stuck inside at home and all you’re looking at is the same four walls, it’s actually quite difficult to create an imaginary world in your own head.

“What got me out of it was re-reading The Butcher Boy by Patrick McCabe. Reading that again reconnected me with everything I love about writing – the fun and the playfulness.”

This being his third collection of short stories, has he ever considered writing a novel?

“I’ve started thinking about my podcast as an on-going auto-fiction novel,” he says. “I adore short stories and I prefer them to something more long-form. It’s the musician in me. Short stories feel like songs. A short story collection feels a little bit like making an album.

“The fun with an album is that you can be like, fuck it, I might do a reggae song or I might have a country song. You can play with all these different tones.”

This short story collection is full of violence, animals and humanity, all tinged with Blindboy’s imaginative lyricism. It’s like Roald Dahl meets Aesop’s Fables for over 18s. Topographia Hibernica takes its name from a twelfth-century English manuscript which dehumanised the people and culture of Ireland to facilitate domination.

“They sent a fella called Gerald of Wales over to Ireland,” says Blindboy. “He actually came over with King John, who built King John’s castle in Limerick. When the Brits were colonising Ireland they had to have a reason and a rationale. You can’t just go into a country and take it.

“So Gerald wrote this book where he looked at Irish folklore and Irish traditions and basically said, ‘These people are animals, they’re not properly human’ and he came up with all these mad bullshit stories. He said that the King of Limerick, in order to become a king, fucked a horse and cut the horses body up and then made a giant soup out of the disembodied horse that he just rode.”

This very story features in the final short story in the collection, also titled Topographia Hibernica.

“The Pope at the time happened to be English so the Normans could go to the Pope and go, ‘These Irish here, they’re not really Christian’,” says Blindboy. “I always think of it like, when the US was invading Iraq and they were like, ‘Oh they’ve got weapons of mass destruction.’ There were no fuckin’ weapons of mass destruction, they didn’t exist. But all you need is an excuse. So the excuse to colonise Ireland was – these people are animals, they fuck animals, they live with animals, they’re not fully human. So we need to civilise them – basically dehumanising the Irish people.”

Themes of biodiversity collapse and folklore, and the boundaries between human and animal, feature heavily throughout the book. Based on two feral cats, the second short story ‘The Pistils Of The Dandelions’ is an emotional rollercoaster that really exemplifies his talent as a writer.

“When you write about two stray cats and you look at Limerick or the world from a stray cat’s eye view, very quickly you get Blade Runner,” says the author. “Living in an industrial estate is post-apocalyptic, it’s Mad Max when you go right down to their level and I loved that.”

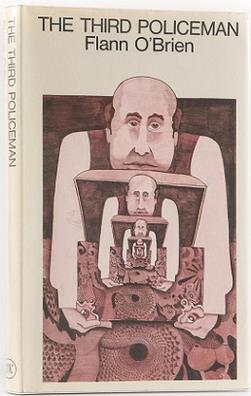

Celebrated Co. Tyrone novelist and playwright Flann O’Brien was a big influence on the Limerick native.

“I love Kate Bush, Tom Waits and Bob Dylan, but Kate Bush is English and Tom Waits and Bob Dylan are American, so I couldn’t really fully relate to them,” says Blindboy. “But when I opened Flann O’Brien and particularly The Third Policeman, I’m like, wow, this is as genius as Bob Dylan, but this fella thinks and talks like me because he’s Irish, so it helped me to find my creative voice.

“All I’ve ever done my entire career, there’s a Limerick-ness there. I’m not trying to be anybody else. I never am. I’m always trying to find the art in the people around me and the city. That’s my unique artistic voice. Flann O’Brien helped me to get that.”

My Happy Place

Throughout the book, Blindboy’s writing is extremely imaginative and strikingly visual.

“I started off painting, I went to art college and studied how to paint,” he reflects. “Sometimes when I’m writing prose, in my mind I’m actually painting. I got diagnosed as autistic about two years ago and it really helped me to understand neurodivergence, the way that my mind works.

“I’m fairly handy across multiple different artistic mediums; music, painting, writing. They all come quite naturally to me and that might be as a result of my autistic brain. I’ve no bother hearing music as writing – I’ve no bother whatsoever seeing a painting as music. These things come to me very easily, as mad as that sounds.”

I ask what he was like as a kid and he admits that the fourth story, ‘The Cat Piss Astronaut’, is almost autobiographical. Based on an autistic six-year-old, it tells of how the boy ended up being attacked by another child’s mother in a local playground.

“I would have been horsing into encyclopedias back then,” recalls Blindboy. “I had this desire for knowledge and wanted to know everything and anything about the sun and the stars. But I had difficulty understanding people. I just started talking to them out of nowhere, ‘Did you know the sun is going to expand and everything’s gonna end?’ This seemed to upset the mother.

“She had never thought about the concept of cosmic apocalypse. She beat me like I was an adult. There was no one around, just her and her daughter. She beat the absolute fuck out of me. I lost the ability to speak after it for about a day.”

This traumatic event didn’t deter his quest for learning. Does Blindboy’s insatiable thirst for knowledge get in the way of sleep and being able to mentally switch off?

“This is the difference between a neuro-tyopical brain and a neurodivergent brain. I don’t know any other way. This is my comfort zone, I love it,” he enthuses. “There’s a childhood curiosity that we’re all born with, and that never left me. My happy place is just being stuck inside my head thinking about things - I love it! What’s stressful for me is being at a party and having to make small talk.

“I was fuckin’ shit at school, I failed my Leaving Cert. Loads of people say to me, ‘Jesus, how did you fail your Leaving Cert, you’re pure smart?’ But what’s really difficult for me is trying to learn in a social environment. That’s very stressful for me.”

Blindboy has developed his own ideal set of circumstances for learning.

“I pace around back and forth, and listen to heavy mental music at the same time. As a neurodivergent person, that’s actually how I learn. I’m flying it when I do that. I’m just someone who is eccentric and strange but now, a psychologist said, oh that’s actually autism.”

An early diagnosis would have helped him as a young lad. Teachers weren’t very nice to him.

“There was no way of getting approval or winning, because everything I did was wrong or bad or disruptive. Eventually I just started identifying with the disruptive part because it’s fun and it’s craic. I failed my Junior Cert too.”

He may have failed his Junior Cert, but he aced his Agricultural Science exam.

“I got 100%, so they brought me up to the office in school saying, ‘What the fuck is going on here? You’re cheating!’ When I was 14, all I gave a fuck about when I was Cypress Hill,” he continues. “I would listen to them all day long and all they’d rap about was cannabis. I didn’t really know what cannabis was, so I wanted to find out.”

Cypress Hill. Credit: Daniel Hastings

Flicking through the pages of his older brother’s FHM, he stumbled across an ad on how to grow marijuana.

“This book was a really solid manual for botany, so I used to spend all day pacing around listening to Cypress Hill, reading everything and anything about how to grow marijuana,” says Blindboy. “Because of that, I sat the Ag Science exam and got 100%. Once I can set the terms for my own learning, I can fuckin’ fly it. I can fly it like a laser.”

Blindboy’s main motivator in all his work is a feeling of meaning.

“Kids love to play and it’s a lot of fun, but when you get to a certain age, you kind of stop playing and creating,” he suggests. “When I’m connecting with a feeling of flow, when art is coming out of me, I’m 100% the happiest I can be. There’s nothing else I want. If I can earn a living while doing that, then I’m successful and I have meaning.

“I’m not motivated by being popular or anything like that. I don’t want to end up in a job that doesn’t provide me with meaning because that would be very, very upsetting for me. Meaning comes from the process.”

Social Media Can Be A Nightmare

There’s no doubting Blindboy’s integrity as an artist. There are layers and layers to this man. You could pick his brain about absolutely anything and he’d give you thoughtful insight. Through his podcast he’s covered diverse topics such as Enya, nuclear war and toxic masculinity. We discuss his consumption of news and how he stays in the know.

“I have the utmost respect for journalism,” he says. “It’s a cornerstone of democracy and it needs to be supported 100%. But there’s journalism and then there’s the business of news media, and that’s about maintaining fear and attention. I have to set up boundaries of keeping myself well-informed, but not ruining my life, because I’m focusing on whatever terrible thing is happening too much.

“I need to keep those boundaries without keeping my head in the sand and it’s tough, it’s daily work. Social media can be a nightmare. I don’t want to come across as selfish, because it’s a position of privilege for me to decide how much about Gaza that I learn. People in Gaza don’t have that fuckin’ privilege, they’re living with it.

“If I’m in a constant loop of terror and fear, and anxiety is gripping me, I’m in a state of shock and I’m no good to anyone. I always place my mental health first, because only when I do that am I of any service to anyone else.”

Knowing when and what to post can be tricky. If people keep quiet on important issues, they can be accused of not caring at all.

“I don’t know how useful it is anymore to speak about serious things on social media,” he considers. “Social media is a platform that’s designed by billionaires – exclusively for us to have incredibly reactive emotions and to polarise opinions and cause us to fight. Because when we do that, the social media company can harvest money from our data. Social media has polarised everything into turn and response combat.

“That’s how the system is set up. So we should all ask ourselves as a civilisation, is this the forum for these really serious discussions? Can I not just post a photograph or a nice cat instead?”

Racists Don’t Care

Our conversation turns to Blindboy’s oldest love, music. As Hot Press has curated the current Pogues exhibition at EPIC, the Irish emigration museum, we chat about the late Shane MacGowan and being Irish in England.

“What I love about Shane MacGowan is how unapologetically Irish he was at a time when to be Irish meant apologising for it,” says Blindboy. “He was doing that stuff at a time when being Irish meant being called a terrorist. For The Pogues’ music to be coming out in the ‘80s was a brave thing, and it represented to the world how important our art is. Shane MacGowan is a legend, he’s amazing.”

While life in England has changed dramatically for Irish immigrants, everyone has stories of bigotry and discrimination throughout the ‘70s, ‘80s and into the ‘90s.

“The British press was calling us all terrorists,” he says. “An Irish accent was something to be hidden on public transport. Even when Gerry Adams would speak on the BBC,they had to give him a voice actor. We were really vilified in the way that Palestinian people are being vilified right now. That was us back then. Racists don’t care.

“They don’t care if someone is Muslim or Sikh – they’re just brown people. It’s important for us to never, ever forget that’s part of our history, and to express it as solidarity with people who are going through it right now. People are very quick to forget. Quick to forget and quick to become the oppressor.”

Limerick Creativity

One constant thread throughout all of Blindboy’s creative output is Limerick City. The book is littered with lovely Limerick-isms for locals to enjoy.

“I love that as a Limerick person you’re finding that. That’s just a little treat for us,” he says. “When I’m being authentic to myself, then my imagination comes out. With writing, what I’m trying to do is control dreaming. Dreams are writing that you don’t have control over.”

Blindboy’s love and loyalty for our hometown is really important, and greatly appreciated by many Limerick natives. Along with our music and sporting achievements, Blindboy has put Limerick on the map for all the right reasons.

“We’ve seen an explosion of creativity in Limerick from about 2018 onwards,” he says. “Denise Chaila, MuRli and God Knows, the Rusangano Family, you had the PX Music lads, Hazey, Citrus Fresh and Strange Boy. We had this explosion of Limerick creativity in the latter part of the 2010s and I think the reason we had that is because of Music Generation.”

Hazey Haze. Credit: Peter O'Hanlon

Hazey Haze. Credit: Peter O'HanlonThe recession hit Limerick hard, but Music Generation kept some local musicians in employment, while at the same time nurturing the talent of the future.

“What you had there was older musicians in their twenties not having to emigrate,” notes Blindboy. “Teenagers coming up learning how to make beats, how to perform and how to make music, and the fruit of all that is the explosion of Limerick talent. It’s proof on a 10-year scale of what happens when you actually invest in local art for kids.”

While we may not have had Music Generation growing up in the ‘90s, we did have Todds (since re-named Brown Thomas) to congregate outside. Every weekend, hordes of teenage music heads, mainly goths, would religiously meet outside the landmark store on O’Connell Street.

“I miss that so much,” admits Blindboy. “Like, I was one of them goths, I used to hang out there. We called it the black door of death! When I got to about 16, all I cared about was music. All I wanted was to be around other people who cared about music as much as I did. We didn’t have social media, so all I could do was walk around in this Slipknot hoodie and hopefully see someone else in a Slipknot hoodie.

“I don’t know who the fuck they are, they’re from a different part of town, they’re from a different school, but because we’re both wearing Slipknot hoodies we’re gonna talk to each other. That was how I learned music, finding people with the same t-shirt as me. Your sense of identity and self, you had to wear it on your school bag, you had to wear it on your t-shirt to express it. You get community from that.”

Limerick people still regularly have to defend the reputation of their city to people who know nothing about it.

“When people say Limerick is a shithole, it’s because they heard someone else say Limerick is a shithole,” says Blindboy. “They’ve been fed a lie. I did a podcast about the wonderful Limerick photographer that is Brian Cross, B+.”

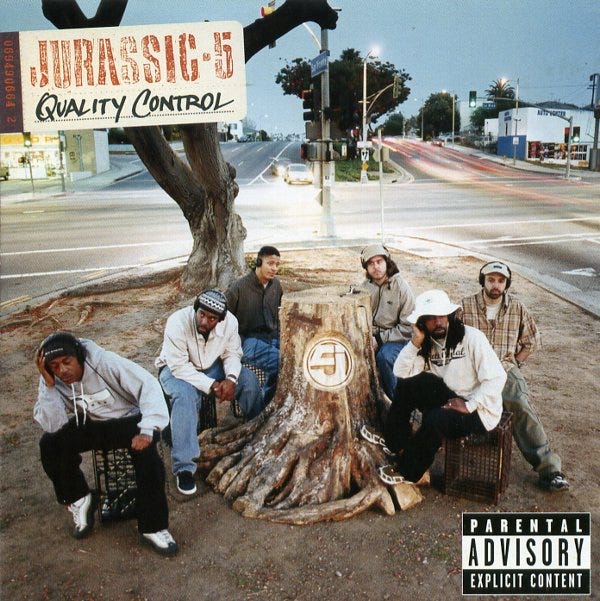

The legendary Limerick photographer moved to Los Angeles in 1990 to study photography at the California Institute of the Arts. Since then, he has done an estimated 100 album covers for artists including Eazy E, Jurassic 5, DJ Shadow, David Axelrod, Warren G, J Dilla, Build An Ark, Cut Chemist, Damian Marley – the list goes on.

Cover of Jurassic 5's Quality Control LP. Photography: B+

“Brian Cross told me the history of why Limerick got called Stab City,” Blindboy continues. “He said in about 1977, there were a bunch of Libyan military pilots out in Shannon, something to do with Aeroflot I believe. They went out in Limerick one night, good looking lads, and one of them shifted some girl. Her boyfriend had a problem with it, so he stabbed the Libyan guy in the eye with a screwdriver. In 1977, violence like that was very rare.

“Because he was a military person, the media just took this idea that Limerick is exceptionally dangerous. This mythology grew from there and we’re still living with the consequences. I still have to defend Limerick all the time. The best thing we can fight it with is our art. We punch above our weight with art, with music in particular. I’m going to keep talking about Limerick and keep representing it as the beautiful, wonderful city that it is and hopefully that Stab City shit will be in the past.”

My Creative Heart

Blindboy is a big supporter of Irish artists. He namechecks April, Ezra Williams, The Mary Wallopers, Kojaque and Sign Crushes Motorist amongst his favourites. The Irish music scene for young artists has blossomed since we were teenagers.

“Making it back then meant – can I do a gig, maybe up in Dublin, and there may be A&R people there, looking to be signed by a US or English label,” he reflects. “The pressure of that, the pressure to be ‘international’ meant that you’d have a band from Dublin or Limerick singing like they were American, or with a bit of British twang. But now, I don’t think these young artists in Ireland are looking for a record deal. I think the fact that there’s no future for musicians in Ireland has freed up the capacity to be very Irish in what you do.”

There’s certainly no shame in singing in an Irish accent anymore.

“I love The Mary Wallopers right, but I’m old enough to remember The Saw Doctors,” he continues. “I think The Saw Doctors are incredible songswriters, I don’t give a fuck what anyone says. The standard of pop songwriting is up there with Prefab Sprout, but The Saw Doctors weren’t cool.

“To sing with an Irish accent was mortifying. Scary Eire were rapping in Irish accents back in 1991. People were mortified! People would leave the venues with red faces, because the lads up on stage think they’re Yanks, they’re rappin’?! Now, all of a sudden it’s cool. The Mary Wallopers are brilliant and they deserve every bit of respect that they’re getting, same with Lankum. Thirty years ago they would have been cringe as fuck.”

The Mary Wallopers at the Troubadour, L.A. Monday October 30. Copyright Riley Glaister-Ryder/hotpress.com

While the creative landscape for Irish musicians is rich, making money is a constant struggle.

“No one is earning a living,” says Blindboy. “Musicians have to present themselves as more successful than they are. That’s part of the brand and the self-promotion. But how do they do that and at the same time say, ‘I’m also not earning any money, can I have some please?’ It’s a dichotomy.”

Blindboy is an adept musician, producer and songwriter in his own right. Over lockdown he wrote over 300 songs while playing video games, livestreaming on Twitch. Does he have an ambition to release his own music?

“The odd time I’d think about it,” he acknowledges. “I would do it if I had the time, but what I’ve got to do is follow my creative heart. Creatively where I’m at right now is writing books.”

But with his musical mind and his way with words, it seems a shame to keep his songwriting potential locked up. Would he consider writing lyrics for say, The Mary Wallopers?

“Jesus, I’d love that,” he enthuses. “I’d love to write for an R&B artist because I adore R&B. To have someone with a class voice singing over my melodies… I would love that if I had the time. When I was 20, I wanted to end up as a producer like Max Martin. One of these people that nobody knows but they’ve written every song in the world.

“Somebody who stays in the studio writing songs and producing for other artists, but no one knows who the fuck they are. Because I don’t really enjoy performing and I don’t really enjoy the spotlight. I just enjoy the creativity."

• Blindboy Boatclub’s latest book Topographia Hibernica is available now via Coronet.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 17 Dec 25

The Year in Culture: That's Entertainment (And Politics)

- Opinion

- 16 Dec 25

The Irish language's rising profile: More than the cúpla focal?

RELATED

- Opinion

- 22 Dec 24

The Year In Culture: From Brat Green to Feuds Created and Abated

- Opinion

- 21 Dec 24

The Best Books Of 2024

- Opinion

- 21 Dec 24