- Opinion

- 21 May 20

Bob Dylan: What Can We Expect From Rough and Rowdy Ways?

We’ve heard three new songs from Bob Dylan in advance of the release of his new album, Rough And Rowdy Ways. The extraordinary power of the three tasters suggests that something very special is in the offing…

As the world shakes in the grip of a global pandemic that has killed hundreds of thousands of people, and continues to dictate the way we must live our lives now, music fans all over the world have taken comfort and pleasure in concerts by favourite artists. From living rooms and outdoor gardens, in solo performances or accompanied by their isolation companions, in organised benefits streamed by venues on YouTube and Instagram, musicians have brought us as close to live music as we can be in these sad dark days and nights. The summer festival season will not happen in 2020; tours have been rescheduled for the coming winter, or scrapped altogether. Some new albums, meant to be launched in conjunction with those tours, have been shelved for now.

Not Bob Dylan’s. Although his tours of Japan, the United States and Canada, slated for April and this summer, have been canceled and rightly too, his new record, the double album Rough And Rowdy Ways, will be released on June 19. It will be Dylan’s first record of original songs since Tempest (2012).

Fans on the principal Dylan internet site ExpectingRain.com are already abbreviating the title, taken from a Jimmie Rodgers song, as RARW. Will it be indeed a barbaric yawp, in the celebrated Walt Whitman phrase, or something more crooney and gentle, as has been the idiom on Dylan’s last three records of ‘American songbook’ covers? Based upon the three new original songs released in the past month-and-a-half that will appear on RARW, and upon the pages of history, I’m going full-tilt with the yawp.

DYLAN LIKES LAYERS

Early in the morning of March 27, while we were sleeping, Bob Dylan dropped a seventeen-minute song into our dreams. ‘Murder Most Foul’, a song that literally circles around the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy on November 22, 1963, provided an immediate place to put our fear, frustration, rage, sadness, and hope all at once. These are, indeed, the times that try men’s souls. Work is hard to concentrate on and hard to hold onto, if you have it. Our poisoned planet fights back with rising seas and new disease; creeds are outworn; governments flail and fail to govern and defend us; parents are terrified for children and vice versa.

Since he was a youth, Bob Dylan has had the phrase “voice of a generation” hung about his neck like the Ancient Mariner’s albatross. I’ve always wondered, though: what generation? Dylan speaks and sings for the people who loved him back in 1962, who’ve come a long way since then — and for those born long before, as well. With ‘Murder Most Foul’, he leaves no question that his voice is, quite simply, ours: Boomers and ZOOMers and folks in between, all of us terrified, angry, and wanting to help and heal and survive. The murder of John F. Kennedy shattered America to pieces; it remains a country still broken. The American Dream, that popular phantasm coined by F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1930 or early 1931, in a short story revision (Fitzgerald applied the phrase, perhaps inevitably, to a desirable girl): did it ever exist? If it did, un-ironically, Kennedy’s assassination swept away that phantasm’s last traces.

Apple Music’s tracklisting for RARW shows that ‘Murder Most Foul’ concludes the double album: a song sixteen minutes and 59 seconds long at the end of an album that will take 70 minutes and 33 seconds to listen to.

Dylan likes to end a record with long songs: ‘Desolation Row’ (11:21), ‘Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’ (11:23), and ‘Highlands’ (16:31, until last month Dylan’s longest known original song) conclude Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde On Blonde and Time Out of Mind. Musically, 'Murder Most Foul’ is as simple and slow in tempo and construction as are these other long compositions. A more elaborate tune would shift the emphasis to the instruments, and not the singer’s voice. Dylan wants you to understand what he is saying.

Though there was speculation upon its release as to when ‘Murder Most Foul’ was recorded, it seems clear, now, that it and its fellows were recorded very recently indeed. Neither Dylan’s voice nor the instrumentals on any of the three recent songs match with the early 2012 sound of the Tempest tracks. At BobDylan.com, where word of ‘Murder Most Foul’ first broke, Dylan’s own statement says “This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting.” For him, “a while back” could mean anything. Remember, this is the man who wrote the line “I have no sense of time.”

The ballad is among the earliest song forms, along with the short lyric and the sung epic poem. Certainly one can call ‘Murder Most Foul’ a ballad, but Dylan is taking the epic for his models these days: Shakespeare, Homer, Virgil, and those more recent masters of the epic and mock-epic, Lord Byron and Walt Whitman. The rhyming couplets of ‘Murder Most Foul’, 'I Contain Multitudes’ and ‘False Prophet’ make them all feel epic, as they are delivered in Dylan’s precise phrasing. He’s always been a superb rhymer, and has always appreciated poets who turn the best rhymes — not for nothing did he inscribe a gift of Byron’s poems to Suze Rotolo “Lord Byron Dylan,” and give his firstborn son the poet’s title as a middle name.

Think of the way Shakespeare delivers almost a body blow with those seemingly simple, rhymed couplets, that say such vital things in the course of a play. Look at Hamlet, from which Dylan takes the title of ‘Murder Most Foul'. The quotation is from Act I, scene V, and is spoken by Hamlet’s father’s ghost, the murdered King Hamlet, as he tells his son of his killing at the hands of his own brother, Claudius: “Murder most foul, as in the best it is; / But this most foul, strange and unnatural.” After a wild and tormented end to the scene after Hamlet receives this knowledge, he says to his terrified friends: “The time is out of joint: O cursed spite, / That ever I was born to set it right.” This couplet is the theme of the rest of the play. The rhyme makes it fix in your head; the words are short and simple and straightforwardly said, making them all the more intense. Dylan does this with his rhymes in all of the new songs.

'Murder Most Foul’ begins with brutality, repeating a story too well known and never to be forgotten. The lullaby comfort in the second stanza of “hush, little children” comes thanks to music: The Beatles, arriving in America in February 1964, and singing five songs including ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ on the Ed Sullivan Show. The comfort doesn’t last, though: ‘Ferry Cross the Mersey’, Gerry and the Pacemakers’ 1965 hit, and the lovefest 1969 ‘Aquarian Exposition’ called Woodstock, give way to the disastrous ‘Woodstock West' of the December 1969 Altamont Speedway Free Festival, at which chaos reigned and Meredith Hunter died. JFK’s murder not only never goes away, it foreshadows the assassination of his brother Bobby, also mentioned here — among many literary and classical allusions that do nothing to detoxify the horror, but rather intensify it.

The movies provide a lead-in to music history, particularly a movie that, in Dylan’s youth, everyone had seen and knew: Gone With the Wind (1939), with Rhett Butler’s last line to his wife, Scarlett O’Hara Hamilton Kennedy Butler, making an altered appearance. What’s New, Pussycat? (1965), Woody Allen’s first-produced antic screenplay with the theme song that Tom Jones made famous, starring Peters O’Toole and Sellers, Romy Schneider, Capucine, and every popular celebrity of that year; and Tommy (1975, based upon The Who’s 1969 rock opera record by Pete Townshend) are both in the song. I love the reference to Terry Malloy, Marlon Brando’s battered longshoreman hero from On The Waterfront (1954), based upon Budd Schulberg’s novel which was, itself, based upon Malcolm Johnson’s Pulitzer-Prizewinning stories Crime on the Waterfront, written in 1948 for the New York Sun.

Dylan likes layers of reference like these; they’re akin to the lessons he shared with us in his Theme Time Radio Hour from 2006 to 2009. The Dylan persona narrating TTRH was similarly didactic, wry, sly, capaciously learned about music and poetry, as apt to pull a quotation from Edgar Allan Poe, Shakespeare, or an old commercial jingle as from a classic song. The TTRH narrator reminded some of Wolfman Jack, who along with his trademark howl is name-checked in ‘Murder Most Foul’ — but he, and the singer of these three new songs, reminds me more strongly of narrators, and singers of songs, from earlier days. The “I” in Dylan’s new songs is a very capital-R Romantic “I”, born of a straight and sinuous literary line running from Byron to Whitman to W.B. Yeats, to Allen Ginsberg to Seamus Heaney to today.

'Murder Most Foul’ concludes with a long litany of commandments. The singer tells you what to play, and sometimes why, in what seems again a harkening back to the style of the shows of TTRH. From ‘Deep Ellum’, or ‘Deep Elem’, Blues to Bobby Darin’s ‘Goodbye, Charlie’; from Elvis Presley’s long black Cadillac to My Fair Lady’s ‘The Street Where You Live’, Dylan’s playlist is one of comfortable familiarity. He’s not out to hit you with new things, but to cheer you up with 20th century popular standards, old American hymns, and classical favourites — ‘The Old Rugged Cross' and Beethoven’s 'Moonlight Sonata’ are here too. 'Murder Most Foul' ends with the recommendation to play itself: the song wraps back into itself, a snake eating its tail, a circle that will be unbroken.

PITHY, WITTY SONG

Dylan’s second midnight special arrived at 12:06 a.m. EST on April 17. It was announced six hours earlier on Twitter, with the hash-tagged phrase “#IContainMultitudes.” Tipped off this time, music and poetry lovers — the phrase famously comes from Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself 51 — stayed up and received another song of litanies, strong orders, and a lot of self-revelation on the part of the singer.

Like Whitman’s poem, this song revolves around the “I” who is the singer. As a longtime literature professor, I’m well trained not to equate this “I” with the author; however, the more Romantic the writer, the harder it is to separate them from the autobiographical elements you wish, as a critic and as a fan, to find in the work. Yet even a confessional poet has some separation between the speaker of a poem and themselves — and Dylan has always been slippery, to put it mildly, when engaging in autobiography.

“Follow me close, I’m goin’ to Ballinalee / I’ll lose my mind if you don’t come with me / I fuss with my hair, and I fight blood feuds / I contain multitudes.” It would be lovely to find Bob Himself in this first stanza. Surely he does like Ireland, regularly touring in the country, and having been a fan and then friend of Liam Clancy, with connections to Van Morrison, Steve Wickham, Bono, Shane MacGowan, and other Irish-born or based musicians. ‘The Ballinalee’ is The Pogues’ most rollicking instrumental performance of them all; remember it on RTE’s The Session in 1987, with Andrew Ranken’s powerhouse drums and Spider Stacy’s untouchable tin whistle? Surely, Dylan fusses with his hair; we’ve seen him do it. He regularly tugs at it and smooths it in concert. Dylan’s hair — what Joe Ezsterhas memorably called “an airborne jungle” — is part of his cultural image. But the blood feuds? Well, it sounds appropriately dramatic and beholden to classical drama, Elizabethan and Jacobean revenge tragedies, and the Wild West — and, of course, it rhymes with multitudes.

Dylan paints landscapes and nudes, he has owned red Cadillacs and had a black moustache, he wears rings on his fingers, and for all we know he plays Beethoven’s sonatas and Chopin’s preludes on his piano(s). Surely, too, he is “A man of contradictions / I’m a man of many moods[.]” Beyond this, and even within this, it’s hard to force him into his own song. The ominous, edgy, challenging lyrics, and the snarly persona delivering them, have most in common to me with the narrator/singer of ‘Pay In Blood’, one of the Tempest songs Dylan has often performed live since 2012.

Speculation about ‘Murder Most Foul’ and ‘I Contain Multitudes’ has included the suggestion that both these songs were recorded in Ireland in 2017. Dylan and his band were in the Dublin area for the better part of a week, and spent a few days at Ardmore Studios in Bray. Maybe so. However, in January 2020 social media posts by or about Dylan’s bandmates revealed that Matt Chamberlain (drummer), Charlie Sexton (guitar) and Tony Garnier (bass) were all in Los Angeles, all in a recording studio. Chris Shaw, the Texas-based GRAMMY-winning engineer, mixer, and producer who first worked with Dylan on Things Have Changed (2000) and regularly since, tweeted in January that he was in LA, “Working on a record now and after throwing 40 mics worth about 200k on everything 90% or the overall sound is coming from a Neuman Binaural head and a 47.” If that’s not a Dylan album being recorded, you just tell me what is. Only the official RARW release will tell which tracks were recorded when, where, and with whom as personnel.

This said, ‘False Prophet’, the third new song, which was released just after midnight on May 8, sounds unlike the other two. And, quite honestly, it’s my favourite of the three. ‘I Contain Multitudes’ and ‘Murder Most Foul’ have a silky, swoony sound, driven by gentle and skilful keyboards — a sound that they share with the background instrumentals for Dylan’s recorded Nobel Lecture in Literature, recorded in June 2017. ‘False Prophet’, on the other hand, is a grindy old blues number with a shuffly, stripteasy, sexy beat. You have to think Dylan knows J. Cole’s ‘False Prophets’ (2016), with its visceral lyrics about artistic creation: “Writin' words, hopin' people observe the dedication / That stirs in you constantly, but intentions get blurred / Do I do it for the love of the music or is there more to me?” He knows Van Morrison’s 40th studio album, The Prophet Speaks (2018). And, of course, Dylan knows his world religions, whence comes the concept of false prophet in the first place.

The song is a denial of being a false prophet, while the speaker makes prophecies throughout. Paradoxical, surely, and also powerful: who and what do you believe? The singer is rather like that of ‘Early Roman Kings’ in his sassiness, seen-it-all-ness, and cocky surety. But hang on, emphasise that seen-it-all-ness for a moment: the tune is taken straight from Billy “The Kid” Emerson’s ‘If Lovin’ Is Believing’ (Sun Records, 1954). In ‘Murder Most Foul’, Dylan tells us what to listen to; in ‘False Prophet’, he literally has us listening to Emerson all along. All his career, Dylan has liked to use traditional or earlier tunes as receptacles for his own lyrics — from Dominic Behan’s ‘The Patriot Game’ underlying ‘With God On Our Side’ to Muddy Waters’s epic and oft-sampled riff from ‘Mannish Boy’ driving ‘Early Roman Kings’.

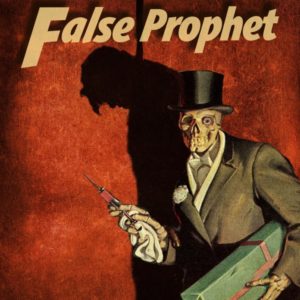

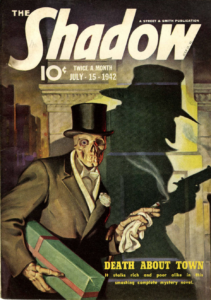

The cover of an issue of Shadow, from 1942, on which the design of False Prophet is based

Dylanologists were quick to find lines from the song in other sources, from the Egyptian Book of the Dead (“I opened my heart to the world and the world came in”) to British Labour politician Aneurin Bevan, who in 1948 said he had created the British National Health Service by “stuffing the doctors’ mouths with gold.” As interesting as it may be to know what Dylan is reading or has read, or what phrases may have stuck in his head and made their way into a song, it is — as ever — what he makes of what he takes that is compelling. This pithy, witty song, throwing off sparks and strangling up your mind, is the most recent and, I hope, most accurate taste of the forthcoming album.

A RECORD FOR THE AGES

What will the rest of Rough and Rowdy Ways be like? That’s easy to say, if you base your expectations on the other original-song albums Dylan has made recently, and the pattern of his past recording. Expect a lot of music history and American history, literary and classical and cultural allusion, and all of it melded and held together with tremendous originality and genius. From the beginning of his career, Bob Dylan has recorded albums of covers prior to intense outbursts of personal creativity. Bob Dylan (1962) featured only two original songs — and then the young singer-songwriter blazed comet-like for a decade. Regrouping and returning to traditional touchstones on Self Portrait (1970), he went on to Planet Waves, Blood On The Tracks and Desire. Once more returning to old folk songs and ballads, the true and familiar and time-tested, and his most important roots on Good As I Been To You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993), Dylan then released the highly regarded original albums Time Out of Mind and Love and Theft.

Rough and Rowdy Ways arrives in the wake of not one, not two, but three (five, if you count all three records in Triplicate) albums of “American songbook” standards. It arrives at a time in the history of the United States of America, and of the world, which is full of fear, pain, confusion, and death. If the pages of Dylan’s own recording history and its reception prove right, Rough and Rowdy Ways will be a record full of comfort and solace, and of lashing, Swiftian saeva indignatio, in equal measure.

It will be a record for the ages, and for all time.

The image accompanying I Contain Multitudes (see above), incorporates a photograph by Andrea Orlandi, Salzburg, July 1996.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 03 Apr 24

The Pogues: 'Dark Streets of London' – 40 Years On

- Opinion

- 20 Nov 23

Album Review: Nealo, November Medicine

RELATED

- Opinion

- 13 Oct 23

Album Review: The Breath, Land of My Other

- Opinion

- 12 Oct 23

Album Review: CMAT, Crazymad, For Me

- Opinion

- 12 Oct 23

Album Review: The Mary Wallopers, Irish Rock N Roll

- Opinion

- 06 Oct 23

Album Review: Reevah, Daylight Savings

- Opinion

- 06 Oct 23