- Opinion

- 08 Dec 22

Bono – Stories of Surrender in Dublin: "Why would he put himself through this? Now we knew…"

At first it was impossible to avoid the niggling thought: he doesn’t need this, so why is he doing it? And then – gradually – we were drawn into the orbit of a powerfully personal psychological, emotional and musical excavation that, by the end of the night, reached depths and attained heights that very few shows of its kind can ever even aspire to. It was, by any stretch, an extraordinary performance by the son of Bob Hewson – better known as your man from U2.

There was more than a crackle of excitement and anticipation on Dame Street. The words of a Bob Dylan song sprang to mind: “There’s something happening here / And you don’t know what it is / Do you, Mr. Jones?” We didn’t know. Not yet. But the adrenalin was pumping, even in the cold outside. Think what it must have been like, at that precise moment, backstage.

Breathing deeply. A huddle maybe. Or even a prayer. Though that’s a ritual from another time, another place, another outfit.

The 3Olympia Theatre has seen some grand premieres and big, star-studded nights – as well as a few different names! – since it first opened its doors in 1879, in the guise of The Star of Erin Music Hall. Charlie Chaplin, Laurel & Hardy, Noel Coward, John Gielgud, Marcel Marceau, Billy Connolly, the late Dermot Morgan, David Bowie, R.E.M. (on a five-night run when the great band from Athens, Georgia were in their pomp), Radiohead, Nick Cave, Sinéad O’Connor, Kris Kristoferson, Tom Waits, Michael Bublé, Hozier and Jedward – the latter in the traditional Christmas panto! – have all graced the ancient stage here, among dozens of globally renowned artists, actors, performers and comedians.

This is where a different kind of history was almost made, on 5 November 1974, when a girder collapsed stage-wards while West Side Story was being rehearsed. Luckily, it happened during lunch break and there was no one in the orchestra pit to be decapitated.

It’s where, in 1987, Irish thespian Alan Devlin blurted out a tortured, entirely unscripted “Fuck this for a game of soldiers” before flouncing dramatically off stage, in the middle of a performance of HMS Pinafore.

Big nights. High drama.

But the build-up to this one was right up there with the biggest and the best.

The President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, was on his way with his wife, Sabina. The Taoiseach, Micheál Martin, was coming too. The Tánaiste Leo Varadkar. Musicians Glen Hansard, Dermot Kennedy, Liam Ó Maonlaí and Barry Devlin were all filing in. Adam Clayton of U2 was spotted. Tom Dunne. Dave Fanning. Roisin Ingle. Brendan O’Connor. Sinéad Crowley. Film director Jim Sheridan. Playwright Conor McPherson. Old Virgin Prunes Guggi and Gavin Friday. I could go on. It was a groovy first night crowd to match the grooviest. The only problem was that there wouldn’t be a follow-on. Because this Dublin gig really was For One Night Only.

Which made the sense of occasion even more palpable. Whatever was going to happen was the beginning and the end of it. Even if someone – who shall remain nameless – screwed up royally, there’d be no room for redemption. This is it. Or would be it.

A GAME OF SOLDIERS

Inside there were familiar faces left, right and centre. And that was just in the audience. When the lights finally dimmed, Jacknife Lee, a spectral blond presence, materialised stage right, facing away from the audience. Gemma Doherty of Saint Sister emerged rear-right to take up position beside the harp. Kate Ellis, equipped with a cello, was located stage left. Down the middle there was a space for the man of the moment to sashay into, which he did a few moments later, a curious mixture of star, and mere human, vulnerable and maybe a little bit self-conscious, parodying the way a star might walk purposefully into the spotlight.

Bono. Him. At it again, as the fella said. And so… we were off.

We still didn’t know what to expect, not exactly. But what even the completely uninitiated could see straight away was that this would be no mere reading from The Good Book. There was a set-up front left of stage, with two chairs positioned in a way that suggested the possibility of an interview or conversation. Elsewhere, there were plain wooden chairs and a matching table. Behind and above Kate Ellis was a screen on which words could be impressed as they were spoken or read. It looked like the set-up for a performance. A one-man show.

There were lapel mics. And there were mics. It was his gig, and so Bono could traverse the stage in whatever way took his fancy, take up positions, climb on chairs and mount the table – and still be heard. U2’s sound magician Joe O’Herihy was at the desk down the back. It all came through crisp and clear.

To anyone who had read Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story, the territory was familiar. Bono spoke aloud passages from the book, recalling the early days in Cedarwood Road, the brutally shocking death of his mother Iris, three men left to make things work – or not – together. How so much was, in a very Irish way, left unspoken. How much was, along with Iris, buried. Deeply buried.

A guitar bequeathed to him by his brother Norman. Trying to play it. The note pinned by Larry Mullen on the noticeboard in Mount Temple school. The first rehearsal in Larry’s house. The shapes that were thrown and the way in which the different personalities of the band members began to assert themselves. A first encounter with the beautiful Alison Stewart.

In a single week, Bono recalled, he joined the band that would soon call themselves U2 (or U-2 as it was styled in those early days) and dated – if that’s the right word – the woman who would become his inspiration, muse and guiding light, the one and only, the Sweetest Thing.

Ali.

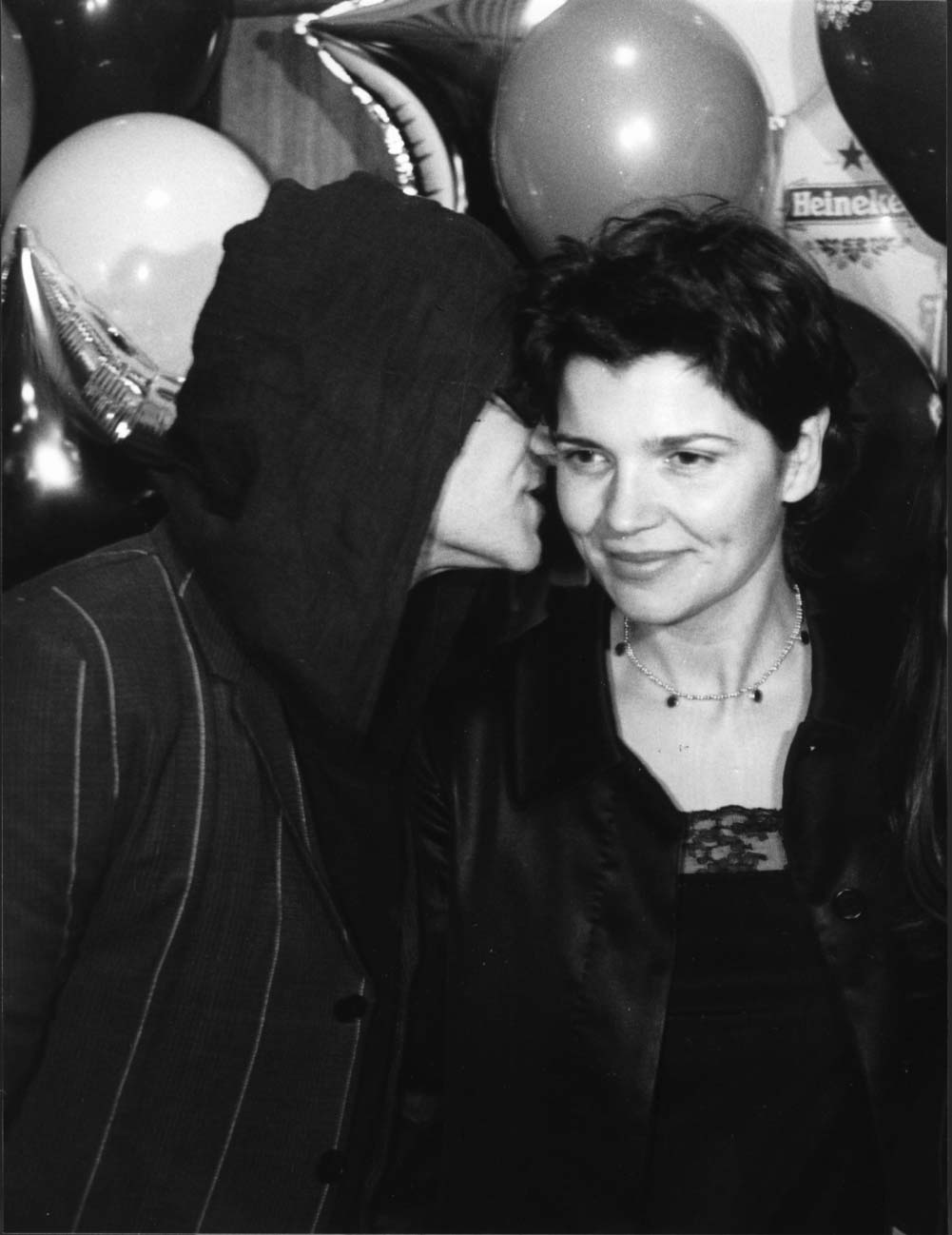

Bono with Ali Hewson

Early on in the show, there were acrobatics. Mount Sinai Hospital. The immortal line “I was born with an eccentric heart…” And with that the speaker started to clamber up onto a chair, and then further up, onto the table, bent over, mimicking the actions of the surgeon as he sawed through the ribcage of the lead singer and frontman of the Irish band U2.

In the book, this tautly written passage is like an arrow hitting the bullseye or splitting the apple on someone’s head. Here, the impact was entirely different.

Beside me, Mairin was empathising in a slightly defensive way. He doesn’t need to do this. So why is he putting himself through it?

I was having a similar feeling, except I could sense the ghost of Alan Devlin hovering. But it was Bono I imagined uttering the forever line: “Fuck this for a game of soldiers” – after, in my mind’s eye, falling off the table and onto the floor, in a cacophony of outlandishly clanging noise. What would health and safety say? Would the insurance cover it?

Man Falls Off Table at 3Olympia Premiere. One Injured. No One Dead.

There were other moments in the early part of the show when Mairin worried: was it going to work? Where I worried. Where Ali, in particular, must have worried. And what about Bono himself? Was he worried? Or was he so far into the moment that there was no room for worrying? Following the breadcrumb trail. Passing the signposts. Only 80 minutes to go. Only 60. A long dark tunnel. Nowhere else to turn. Nor to run. Just… keep... going...

As the monumental scale of the ask, and the ambition driving it, became clear, one thought rose above the welter of competing emotions.

“He’s a brave fucker.”

Paul Hewson.

He really is. Taking on a task as vast and as risky as this when he could be at home sipping a glass of the good stuff. Walking the tightrope without a safety net. Nearly two hours up there. No Adam. No Larry. No Edge. Carrying the can every step of the way. On his own.

CONFESSION BOX RAW

Alright, not entirely on his own. With the brilliant Jacknife Lee in charge of triggering samples, banging percussion and generally stitching things together, Kate Ellis getting down and funky on the cello and Gemma Doherty sprinkling melodic magic over the mix, he had a Gang of Three behind him on the songs. They played against expectations, making the tracks woven into the story sound as un-U2 like as possible, while also retaining the ineluctable core that makes them what they are: U2 classics.

But he had to carry the narrative. Remember the sequence. Tell the story. Strike the right poses. Make people laugh. And then do all the singing and dancing as well.

‘City Of Blinding Lights’ and ‘With Or Without You’ were held up to the light and made to look different and it worked. No karaoke tonight, thank you.

Bono doffed his cap to The Ramones and described what it was like, pushing past the outside of the envelope to write a song called ‘Out Of Control’. It was all new then. He captured the machinations of being in a band – he used U2 manager Paul McGuinness’ phrase “a baby band” with the hint of a wry chuckle – and the fierce intensity that drives young people, thrust together in a rehearsal studio.

Him getting stroppy. Tearing strips off his compadres. Asking Edge to make a noise that sounded like a dentist’s drill. Then grabbing the guitar in frustration off a bemused Edge and plugging away at one or two strings. De-n-n-n-n-n-n-n-n-n-n-n-. Edge taking the piss. Keep going. It really does sound like a dentist’s drill!

U2

Bono laughing now at Bono back then and us lot laughing at him laughing. And then it happened. The dentist’s drill turned into something else, as the cello picked up the rhythmic thread. And – the anxiety for the main man’s health, well-being and sanity being shunted into a siding – we were in the moment too, the inexplicable power of a noise fabricated and arranged in the indescribably right, most spookily compelling way transporting us out of the running commentary and into the slipstream of the now. Here she comes: ‘I Will Follow’ in all its hormone-fuelled teenage urgency.

“A boy tries hard to be a man / His mother takes him by his hand / If he stops to think, he starts to cry / Oh, why?”

Not a bad question for an 18-year-old to ask. And then the chorus, which always gave the impression of being a half-formed thing, made up on the microphone, a version maybe of speaking in tongues. “If you walk away, walk away / I walk away, walk away / I will follow”...

“What’s it about?” we asked each other. Bono talking. I seem to remember him saying “I don’t know what it’s about.” With a question mark superimposed at the end. A statement that was really a query.

He wasn’t finished yet. I had chased this detail down in The Stories Behind The Songs Of U2. Now, I was back in that moment.

Remembering how Bono had said – sometime back in the early days – that the song was a sketch about the unconditional love a mother has for a child. In a way, this was like following a wisp, but that was the point. Me speculating that there is more to it than the mother loving the boy. That there is a palpable yearning in the lyrics that seems to have more to do with the flip-side of the coin: the boy loving the mother, and what that child feels when his mother walks – or is taken (By what? By whom?) – away from him.

Sometimes the key lines in ‘With Or Without You’ are where it is really at: “And you give yourself away / And you give yourself away.” A writer doesn’t always know what is being said, or not fully, because language has a way of sneaking meanings in, that speak of backstories that are buried in the subconscious. That word ‘word’. In this sentence. How?

What a child feels when his mother walks – or is taken – away from him. An urge to follow that could possibly be described as what? The thought crystallised. As suicidal maybe. I’m fucking outta here.

“The song is a suicide note,” the onstage Bono said.

Suddenly, here in the 3Olympia Theatre, we had been drawn into a whole other world of pain and emotional vulnerability. We could see – he’s been standing there in front of us, not fifteen yards away from where I am sitting – just how alone he really was, and how out of anything that might be described as his comfort zone.

There is an even greater sense of exposure, of emotional nakedness, when this deeply personal stuff – this self-reflection, this “digging down in the depths of your spirit” – is articulated onstage rather than on the page. Here, tonight, it felt extra raw. Wrestling with yourself raw. Hearing what’s coming out of a confession box raw.

Why is he putting himself through this?

A second’s thought only now. Then it was gone.

“What no one in that rehearsal room, including me,” he said, “had thought about was Iris Hewson resting under the ground not a hundred yards from where we were playing. In all the time we rehearsed there, I never thought about it, or even once visited her grave. My mother was dead. Literally, but also emotionally, to me. So I thought.”

That second’s thought is gone, because it is clear now that he’s been searching. Down all these days. The point of taking this leap into the unknown is to see what can be found in the depths of your own – his own – spirit. And to see what might be reclaimed from the rubble of the past, the import of which too often eludes us all our lives.

SECTARIAN TENSIONS

You could posit the idea, I suppose, that – as he stood there on the 3Olympia stage, following the breadcrumb trail – the singer wasn’t entirely alone in another way too. That the Hewson paterfamilias was there to help him through this soul mining.

Well, sort of there.

The chairs, it turned out were for him and his father Bob, who died in 2001. In front of us, Bono sat down in Finnegan’s Bar in Dalkey. His father began the conversation – as he did every time he met Bono – with a question: “Anything strange or… startling?”

It’s a question my own father also used to ask. Maybe it came from a movie. “Anything strange or… startling?” Except Bono was intoning it now, in his father’s best nearly posh Dublin accent: “Anything strange or… startling?” Half looking down his nose. Giving the other fella a semi-beady eye. Who is the real boss here?

Bono is a good mimic. That much we knew but only in a casual sense. I had no inkling that he’d be able to turn that ability into the basis for a hilarious comedy routine, spun out in front of more than a thousand people, that would lend a brilliant thread of humour to what – it was now becoming clear – was a proper, full-scale, emotionally courageous, highly theatrical and often brutally honest one-man show.

Paul asking his father if getting a call from the greatest singer in the world, Lucianio Pavarotti, might count as strange or startling? His father’s grudging interest. A hint of desperation in B's desire to impress the man without whose loins he’d never have seen the light of day.

1996. We were back in Finnegan’s then, in the Sorrento Lounge, as – for the benefit of his father – Bono launched into re-creating a brilliant impersonation of the great Italian tenor, in full persuasive mode, as he tried to track down the man he called ‘Bono, Bono, Bono’, and to persuade him, and his fellow U2-ers, to play a show in Modena, Italy in support of the War Child charity.

All of this behind-the-scenes mockery of self – and occasionally of others, including mimicking his fellow band members to laugh-out-loud effect – is even funnier onstage than in the book, most notably in this instance because Bono clearly has the great Luciano down to a T.

His description of Adam and Larry’s preference for hiding from Luciano when he pops into the U2 recording studio unannounced had the whole room in stitches.

The guy is a fucking comedian.

It went on. Bob the father in Modena. Invited to say 'hello' to Princess Diana, but refusing to have anything to do with royalty. Until the Lady herself steps into the room and 800 years of oppression melt away. Her charitable endeavours acknowledged by the da. With just the right amount of gravitas.

Astute observations about Ireland are peppered throughout Stories Of Surrender. That the best way to understand the Irish mind is to imagine it as a pub. The sectarian tensions. The Roman Catholic who drinks Bushmills – a Protestant drink. And then there is the build-up to ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’, rightly identified as the stand-out song on War. In the book, Bono describes the drums as providing the hook, but it is performed here without Larry and retains its visceral power. It reminds us all of the reality of the island we lived on for almost 30 years, from the beginning of the 1970s till almost 2000: a place torn apart by violence, murder, butchery and bloodshed.

“There’s many lost,” he sang, “but tell me who has won / The trenches dug within our hearts/ And mothers, children, brothers, sisters torn apart / Sunday Bloody Sunday.”

He sang ‘Where The Streets Have No Name’, ‘Pride In The Name Of Love’, ‘Desire’ and ‘Beautiful Day’ in ways that amplified the yarns or gave them context. Even ‘Vertigo’ – a song that hangs on its powerful opening and big bass and guitar riffs – was re-imagined in a way that worked in this stripped-down theatrical context.

We heard about the journey to Ethiopia in 1984 with Ali. Live Aid. Bob Geldof. “He is the most articulate man I’ve ever met,” Bono said by way of tribute. He described campaigning to convince wealthy nations to Drop the Debt. Bono perfectly mimicking Geldof in full-on demand mode. “Give us the fucking money!”

Bono beside him. “I had the easy part,” he said, or words to that effect. “All I had to do was say… (in a little boy voice) ‘Please?’”

Credit: Ross Andrew Stewart

TEARS BEING SHED

In the book, the rise of ONE and RED is a long story of horse-trading, getting to see powerful men and Presidents, and some increasingly powerful women. Making the case. Sitting down with the enemy. Talking. Pleading. Persuading. Getting lucky. Winning.

Here he established the distinction between charity and justice and got down to brass tacks quickly, the screen to the left ringing up the facts and the numbers. 100 billion dollars in aid from the United States of America. As he says in the book, in a humorous rebuff to his friend Warren Buffet, who had accused him of selling out for a plate of lentils: “That’s a lot of lentils.”

There were moments when it seemed like the emotional weight of doing this show in Dublin might almost be too much. Where he had to pull back from a brink, beyond which there were tears lurking. In particular, when he openly declared his love for Ali, who is the real hero of both Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story and Stories Of Surrender, it seemed like they might come rushing out – in which case we'd all be in real trouble. But he managed his breathing. Held his equilibrium. And pressed on like a true thespian in pursuit of the final curtain.

The arc of the story was lovingly and movingly shaped to bring it back to Finnegan’s and to Bob. And to the baritone who thinks he’s a tenor. Bono has a theory that when his father died, he handed on a gift to the son who had brought him to see Pavarotti. In the months afterwards, Bono felt his voice change. The baritone who thought he was a tenor started to hit the higher notes in a different way. His voice became richer. He started to sound like his father. Or maybe even just a little bit more like Luciano himself.

One of the most beautiful moments in the stage show came when the divine sound of Pavarotti singing ‘Miss Sarajevo’, which of course was originally released as a track by Passengers rather than U2, wafted from the speakers – and with it the realisation of just how close that extraordinary, timeless track came to not happening. The story of how Bono and Edge (but not Larry and Adam) made it to Modena – and implicitly how the record did finally get made – is at the heart of Stories Of Surrender.

As is the growing awareness, the epiphany, that, as a singer, you are permanently in search of that ecstatic moment when you are not singing the song, but – by surrendering yourself, and your ego to it completely – you are in the song and it is singing you.

By now, there were tears being shed in the 3Olympia Theatre, by numerous members of an audience that had been treated to one of the most remarkable, individual, honest and personal one man shows it would be possible to imagine.

There was one final flourish, as Bono took on the role of Bob, stepping up to deliver a soaring performance of ‘Torna a Surriento’ – or ‘Come Back to Sorrento’. Dating from 1902 – or maybe even earlier – the song has been recorded dozens of times, including by Enrico Caruso, José Carreras, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Placido Domingo and, of course, Luciano Pavarotti. Here, the U2 lead singer joined that illustrious company as an equal, finally it seems coming to terms with the complicated legacy of his relationship with his father, Bob Hewson.

Why would he put himself through this? Now we knew…

A FINE CAREER AHEAD

In the street outside there was a crackle of a different kind in the aftermath. “Absolutely astonishing,” Barry Devlin of Horslips said. “There are guys who’ve been doing this all their lives and he just steps up and does it. Only better.”

“Amazing, really,” John McColgan, director of Riverdance: The Show, said. “I had no idea he’d be able to carry that off but he did it brilliantly.”

The compliments were flowing. Everyone sensed that it was a privilege to have been there. For One Night Only indeed.

Around the corner, a gathering was taking place. Jackknife Lee, starting to relax, chatted amiably. “That was fantastic, wasn’t it?” Glen Hansard said. “That has raised the bar for the rest of us. We’re blessed to have him.”

Ali was as serene as always, the very public acknowledgement by her teenage boyfriend of a deep love that has lasted over 40 years notwithstanding. “I’m like one of those football managers you see on TV,” she laughed. “After a good result, it’s like ‘I’ll take that’.”

Bono was beginning to relax too. “It’s true,” he said about the nagging feeling we'd had at the start, that he didn’t need to do this. “I didn’t need to, but I wanted to.”

I couldn’t get the line that had occurred to me fifteen minutes into the show out of my head.

He’s a brave fucker! This Paul Hewson, son of Bob and Iris; brother of Norman and Scott; husband of Ali; father of Jordan, Eve, Eli and John; and member of the once little-known Dublin four-piece U2.

“The character that people see,” he said, “you know and Mairin knows, that’s not me. I wanted to reclaim my humanity. I wanted to be me.”

And he succeeded. The real Bono stood tall. No one who saw it can have been left in any doubt. No one who reads Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story should be either. To echo Ali, as a football pundit might say, “That was different class.”

On the basis of what we’ve seen so far, Bob Hewson’s son has a fine career ahead of him. If he sticks at it...

Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story is out now.

Read our recent Q&A with Bono here.

The special festive issue of Hot Press is out now, featuring cover star Dermot Kennedy – who discusses his new album Sonder, the hard graft behind the fame, his newfound confidence, Glen Hansard, Bono, Inhaler, and loving football “as much, if not more, than music...” Pick up a copy in shops now, or order online below:

RELATED

- Opinion

- 16 Dec 25

The Irish language's rising profile: More than the cúpla focal?

- Opinion

- 13 Dec 25