- Opinion

- 25 Jan 22

The Happy Hunting Ground Of All Minds That Have Lost Their Balance.

If it’s not too fanciful – and he does it himself, so it’s fair game - one can find some Homeric parallels in the career of Daniel Mulhall. He’s spent years travelling the seas of the world, buffeted by the winds of international diplomacy, serving as Ireland’s ambassador everywhere from Malaysia to Berlin - there were tsunamis of different stripes in both locations - to his current posting as our man in America. Ireland has always been his Ithaca, however, and the literature of his homeland a constant companion on his travels, with a special fondness for Yeats, and a near-obsession with the work of one James Joyce. Perhaps he sees something in the wanderings of Bloom that speaks to his own travels, or perhaps he just likes a good yarn wrapped in a complex puzzler.

With expert timing, given the fast approaching centenary of the publication of Ulysses in Paris in February 2, 1922 – Joyce’s 40th birthday - Mulhall has presented a book report gleamed from a life spent with Joyce in his suitcase. The Ambassador comes across as a very pleasant fellow throughout and proves an excellent guide through daunting terrain. Here’s his novel approach to the novel; simply skip over the difficult parts to get to the good bits. This might be greeted as heresy in some quarters – and cause several academic heart attacks – but it seems like a capital idea to me

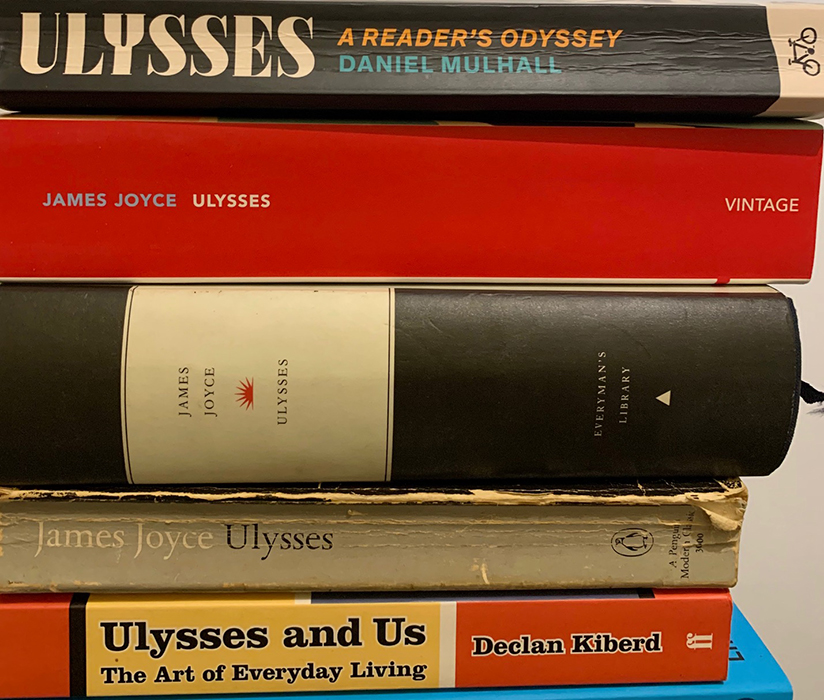

As an undergraduate out in UCD, there was no getting around Ulysses so I steeled myself and went in. Stephen Dedalus chats to his mates, then he goes to have a word with the headmaster of the school where he’s temporarily working, all the while feeling guilty about his Ma’s passing and how he acted. Hold on, this wasn’t so bad, what were they all going on about? But then you get to the 'Proteus' episode, where it all goes a bit “ineluctable modality of the visible”, and the head scratching starts. Mulhall relates a similar experience the first time he had a go too, as does Anne Enright in her introduction to the latest Penguin/Vintage reprint of the book itself. “The first two episodes – all fine. Surprisingly easy,” she writes. “Then the book unlooses itself entirely in the mind of Dedalus and starts to dream.”

I suspect it’s at this point that most sensible people put the book back on the shelf with a promise to come back to it and get on with their lives. Avoid this scenario, says Mulhall, by reading these first two chapters, referred to Homerically as ‘Telemachus’ and ‘Nestor’, then skip to ‘Calypso’ (4), ‘Hades’ (6), ‘Lestrygonians’ (8), ‘Cyclops’ (12), and then the big finish with Molly in bed in 7 Eccles Street for ‘Penelope’ (18) These will, in Mulhall’s estimation, give the reader a flavour of Joyce’s achievement and perhaps encourage them to tackle the trickier sections, and they are trickier than a magician's manual. Anyone who tells you otherwise is taking through their straw boater or has never gone near the yoke in the first place.

As soon as Mulhall lays out his shortcutting map – an easier notion that Bloom’s crossing Dublin without passing a pub conundrum – you know you’re in the hands of someone who takes the whole thing seriously, but not too seriously, which is, if I had to hazard a guess, an approach that Joyce himself would have approved of. That being said, the ambassador wades in, and tackles each chapter as they come up, offering insight and erudition, without being afraid to throw his hands up the odd time and mutter a whispered "Ah, Jaysus!”

Advertisement

The Tower Of Babble

The Tower Of Babble"A Little Pretentious"

If you have managed the admirable feat of making it through all 780-odd pages of Joyce’s behemoth - and, as Enright points out, it’s acceptable to feel both brilliant and “a little pretentious” as a reward - then this retelling will bring it all back to you and set the head gears cranking. I wish that I too had a few bob on Throwaway in the Ascot Gold Cup and the gag based around Bloom and his newspaper he gives to Lyons is a good one. Who is the “lankylooking galoot” in the Macintosh at Paddy Dignam’s funeral? “Who is the third who walks always beside you?... wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded,” asked T.S Eliot in The Waste Land, published that same year. I may be getting slightly carried away here.

Does Stephen Dedalus' theory about Hamlet, as expounded in the National Library, where Shakespeare is the father's ghost, hold any water or, and here’s my two cents, is Bloom Joyce’s Danish prince, a man who knows he has been wronged – Blazes Boylan’s ‘visits’ with Molly Bloom – but spends far too long thinking about it rather than acting? In fact, as Mulhall points out, he seems, in the ‘Sirens’ episode, to be almost worried that Boylan might miss his appointment with Molly – “Has he forgotten? Perhaps a trick.” Surely he should, when he sees his rival in The Ormond, take him to task, but he muses on it instead. Later, in the ‘Nausica’ episode, after his own cock has crowed for Gerty, he’s reminded, three times over, of his cuckold status by a near-by cuckoo clock, after he has written ‘I am a’ in the sand, lest the reader still be in any doubt.

That theory could be just as windy as Stephen’s, and extracting anything out of ‘The Sirens’ is tiring work. “It took Joyce five months to write’ Sirens’ and it could take five months to come to terms with it,” says Mulhall, warning the reader to not expect much and referring to Joyce’s pal, the poet Ezra Pound, who, in response to this section of the novel, asked Joyce if he “got knocked on the head or bitten by a wild dog”? For critic Hugh Kenner ‘Sirens’ is “the advent of engulfing stylistic idiosyncrasies” and that the Blazes/Molly tryst sends the wandering Bloom into ‘freefall’. In other words, if you thought Ulysses was tough going up to this point, then we have bad news for you.

Advertisement

Before the book descends into a total head-buster altogether, the episode that Mulhall identifies as a favourite takes place in Barney Kiernan’s pub on Little Britain street. ‘Cyclops’ is perhaps the most enjoyable and re-readable section, and it's here, in the pub, that Bloom becomes the everyman hero, the Irishman as he should be, declaring against violence, racism, nationalism and all the rest of it, and voting for something better.

“-Force, hatred, history. All that. That’s not life for men and women, insult and hatred. And everybody knows that it’s the very opposite of that that is real life.

-What? Says Alf.

-Love, says Bloom. I mean the opposite of hatred.”

Love loves to love love.

The Mighty Dead

As already pointed out, Mulhall is refreshingly realistic about the difficulty of swimming through Joyce's treacle, and when he refers to the ‘Oxen And The Sun’ as “a beast of an episode” you can take his word for it. Joyce himself called it the book’s most difficult section “both to interpret and to execute”. ‘Don’t be afraid to hit the skip button,” advises our guide, and he’s right, it’s hard work. Here’s another hair-brained theory from this corner. The episode takes place in Holles Street Maternity Hospital, Joyce said the organ that pertained to this section is the womb, and it’s presented in nine sections – as in months – each one written in an English prose style, from the Anglo-Saxon era up to Joyce’s time. Taking all that into account, is Joyce presenting his own work as the birth of the new thing, as it undoubtable was/is? The nine months/sections present the stages the English language had to get through to give birth to him, the birth of the new word. In the ‘Oxen Of The Sun’ section of The Odyssey, the boat is struck by a thunderbolt and only Odysseus survives. Is Joyce the thunderbolt here, striking literary history, leaving Ulysses as the only survivor? Where could literature go after this except to drift untethered in the Anna Livia Plurabelle river of madness that is Finnegans Wake, or is it all just spilled seed on Sandymount strand? "Nonsense!" you cry from the back, banging your mug on the wood. "Have you nothing better to be doing?" You're probably right, I’m only speculating on a few hypotheses, and sure aren’t errors volitional and the portals of discovery?

This is one of the things that’s so marvellous about Ulysses; Joyce managed the miraculous by condensing all human life into one Dublin day and it allows you to indulge in this kind of harmless speculation and theorising. As Enright quite correctly points out, going in without a guide could be an act of arrogance, and if it hadn't been for the Cliff Notes and Professor Declan Kiberd, I'd still be out in Belfield. If all this anniversary talk has prompted you to consider having another go, then Mulhall is a good man to have in your camp. He concludes with a mention of Adam Nicolson’s enjoyable 2014 book The Mighty Dead: Why Homer Matters and quotes Nicolson's summing up of what was special about the blind bard, “the ability to regard all aspects of life with clarity, equanimity and sympathy, with a loving heart and an unclouded eye.” Mulhall reckons “that’s our Leopold” but I’d argue it sums up Joyce himself, the man whose endlessly fascinating work, to borrow a phrase from Stephen Dedalus, is veined with “the eternal affirmation of the spirit of man”.