- Opinion

- 01 Mar 19

Brazil: How has it come to this?

It has been said that an alt-right, misogynist, racist, homophobic, pro-torture, dictatorship-praising populist has been elected as President of Brazil. Is that a fair representation of what Jair Bolsonaro is all about?

IN January, Jair Bolsonaro, began his reign as President of Brazil. His election followed a bitter campaign, which has left the country fiercely divided – and many living in fear. Bolsano promised “liberation from socialism, inverted values, the bloated State and political correctness.” So what does that mean to people in the artistic community?

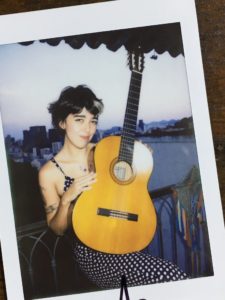

Mariana Romano is a musician, signed to Selo Risco, a Brazilian record label. She lives in Rio de Janeiro.

“On the day of the election, when I saw the results, I cried hysterically,” she recalls. “I live in a very artistic, hippy-like neighbourhood in Rio and I thought somebody else was going to win here at least. But no, the majority in my own neighbourhood voted for Bolsonaro. It was devastating.

“It has left me thinking,” she adds, “who are my neighbours? Who are these people I see every day? I’m struggling to come to terms with the fact these people elected someone so incredibly racist, misogynistic and homophobic. Nowadays, nobody knows who to trust. The country has become divided left and right. It almost feels like everyone is the enemy. We barely recognise our country.”

There are reasons for women in particular to feel threatened by the drift backwards, which Bolsonaro’s election represents. The 38th President of Brazil has a long history of insulting women, as well as the LGBT+ community, black people, refugees, and other minorities.

“I’ve got five kids,” he said. “Four of them are men, but on the fifth I had a moment of weakness and it came out a woman.”

About the possibility of his children dating someone of colour or coming out as gay, he was equally crude.

“I don’t run the risk,” he said. “My children were very well raised.”

His hatred of gays is well known.

“I would be incapable of loving a homosexual son,” he said crudely. “I’d rather my son died in an accident than showed up with some bloke with a moustache.”

And in a bizarre 2013 interview with the writer, comedian and actor Stephen Fry, Bolsonaro claimed that “Homosexual fundamentalists” are brainwashing children to “become gays and lesbians to satisfy them sexually in the future.” And he proclaimed: “Brazilian society doesn’t like homosexuals.”

Fry later said that the interview was “one of the most chilling confrontations I’ve ever had with a human being.”

Meanwhile, in relation to immigration, Bolsonaro said: “The scum of the earth is showing up in Brazil, as if we didn’t have enough problems of our own to sort out.”

A COUNTRY IN PERPETUAL CRISIS

So how did this retired army officer, who had largely been a marginal figure in the Chamber of Deputies since 1991, become President of the fourth largest democracy and ninth largest economy in the world? To which the best answer is probably: my, what a tangled web we weave.

Attempting to understand Brazilian politics is not for the faint-hearted. There are 27 political parties represented in the Chamber of Deputies, covering all shades of left and right, across the 26 self-governing States that make up the entire of the country. Brazil was controlled by a military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985. The end of the dictatorship was followed by a period of hyper-inflation and instability, before relative economic calm was established in the 1990s. When the Worker’s Party (PT) acceded to power in Brazil in 2002 – Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva was elected President, winning 46.6% of preferences in the first round and 61.3% in the run-off – the hope was that inequality and discrimination would finally be challenged effectively.

Things may have gone well initially, but the party was plunged into crisis following a series of corruption scandals. These included a housing scandal, in which R$100 million went missing; an electoral scandal, in which cash from PT State funding was used to buy a dossier containing material for use in attack ads against other politicians; corruption accusations, involving slush funding and bribes for votes, which led to resignations and defections from the Party; and further accusations of corruption and money-laundering which have led to a series of arrests (including – as recently as 2018 – the former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva himself).

All of these setbacks notwithstanding, the Brazilian economy continued to grow at a prodigious rate, and incomes soared. After two terms and eight years as President, da Silva was followed by his anointed successor, Dilma Rousseff, elected as President in 2010 and again in 2014. However, Brazil’s first female President was impeached in 2016 for “criminal misconduct and disregard for the federal budget.”

And so it is not hard to understand why Brazilians were left feeling deeply disillusioned and searching for something different when the 2018 election came around. Apart from corruption, endemic violence has been getting worse in Brazil’s major cities for years. Meanwhile the health system has been in a state of near collapse. Its extraordinary economic potential notwithstanding, Brazil has been in perpetual crisis.

And into the breach stepped Jair Bolsonaro.

THE ROLE OF FAKE NEWS

Bolsonaro successfully exploited the anti-Worker’s Party sentiment which had gripped Brazil. He painted the PT, and other leftist parties, as communists, who were responsible for all Brazil’s ills. And he struck the right populist chord when he promised to “lock up” crooked politicians.

None of that would, in the past, have been enough to propel him from 20% in the ratings to eventual victory. As with many recent elections across the globe, however, he was assisted greatly by the proliferation of fake news.

Brazilian’s love WhatsApp. Most people are part of numerous WhatsApp groups – often with hundreds of participants. As has been demonstrated at a terrible cost in India, it is the perfect breeding ground for fake news.

It is important to acknowledge that fake news was being generated by both left and right in the Brazilian election. But one outlandish story in particular made a huge impact. It claimed that the Worker’s Party candidate, Fernando Haddad, had equipped creches with erotic baby bottles shaped like a penis; and that he had supplied ‘gay kits’ to teach homosexuality in schools. It was utterly preposterous.

“Bolsonaro put very little money into the campaign,” Mariana Romano says, “but it was fuelled by the internet – mostly WhatsApp. How did a person who is so incompetent build an image based on thin air? It was through WhatsApp and social media. It was a phenomenon.”

The newspaper Folha de S.Paulo revealed that 156 pro-Bolsonaro businessmen had, between them, paid millions of dollars to companies, who used foreign telephone numbers to bombard people with anti-Haddad messages, employing lists of WhatsApp users that had been obtained illegally. As with Brexit in the UK, electoral laws were flagrantly breached.

There are of course, similarities to another populist leader of the Americas. Bolsonaro, is often labelled “Trump of the Tropics.”

Romano believes the comparisons are fair.

“His plan for government was like a PowerPoint that didn’t have more than 100 words. Their way of thinking about fixing problems is so naïve. They only think about the next step, not two steps ahead. Their thinking is: ‘We have security problems, let’s put guns in everybody’s hands’. It’s crazy.

“Even Marine le Pen doesn’t like Bolsonaro. What does that say about the man, if even the shitty people don’t like you?”

Given his desire to loosen gun laws, it is hardly surprising that Bolsonaro has suggested the country return to the hardline politics of the 1964-1985 military dictatorship. We may yet see him, like the repulsive Erdogan in Turkey, make a move to establish a dictatorship.

“We have never had as much military in politics,” Mariana says. “Even more than when we were a dictatorship, which is super scary. These people are not trained politically. Just like many other places in the world, people in Brazil seem to be praying for the ‘olden days’. It’s a kind of crazy, misguided nostalgia that makes no sense.

“Bolsonaro just announced an anti-crime package that makes it easier for policemen to kill people on the job and not have any consequences,” she adds. It is against that background that Mariana, her friends and her family are thinking about leaving Brazil for good.

“I am really considering emigrating,” she says. “I was just talking with my friend who lives in Portugal, and she was telling me about life there.

“Here in Rio, every day I see people with guns, people getting robbed,” she says. “I think to myself: what am I going to do here? I want to live my full life and now we are faced with four years of things going further and further downwards.

“For the future, I have no expectation. Every day is a new tragedy in Brazil. We hope for the best, but expect the worst.”

Pictured above: Mariana Romano

RELATED

RELATED

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 11 Nov 22

World Cup Preview: "Head on the block time: we’re backing Tite to fix the lingering problems in his team"

- Opinion

- 02 Sep 20

Deliveroo Rider Thiago Osorio Cortes Killed In Hit and Run In Dublin

- Sex & Drugs

- 16 Dec 19

Quotes of the Year 2019: Highlights from our conversations with politicians

- Opinion

- 26 Jun 19

Milton Nascimento Takes Flight at Paradiso, Amsterdam

- Opinion

- 28 Jan 19