- Opinion

- 16 Jun 22

Eoin Ó Broin: A Future Housing Minister Speaks

Sinn Féin are on a high – legal of course – in the wake of the Party’s historic poll-topping victory in the Northern Ireland local elections, and soaring poll ratings south of the border. Against that backdrop, Hot Press visits Leinster House to talk to Eoin Ó Broin, the Sinn Féin spokesperson on housing about how to get houses built fast, making religious orders pay what they owe to the State, the National Maternity Hospital, the rise of the Alliance Party – and the prospect of a border poll.

South County Dubliner Eoin Ó Broin is a considered, well-informed and highly articulate man, who looks younger than his 50 years. Representing his party as TD for Dublin Mid-West since the 2016 general election, his CV includes spells at Blackrock College, a degree in Cultural Studies from the University of East London and an MA in Irish Politics from Queen’s University Belfast.

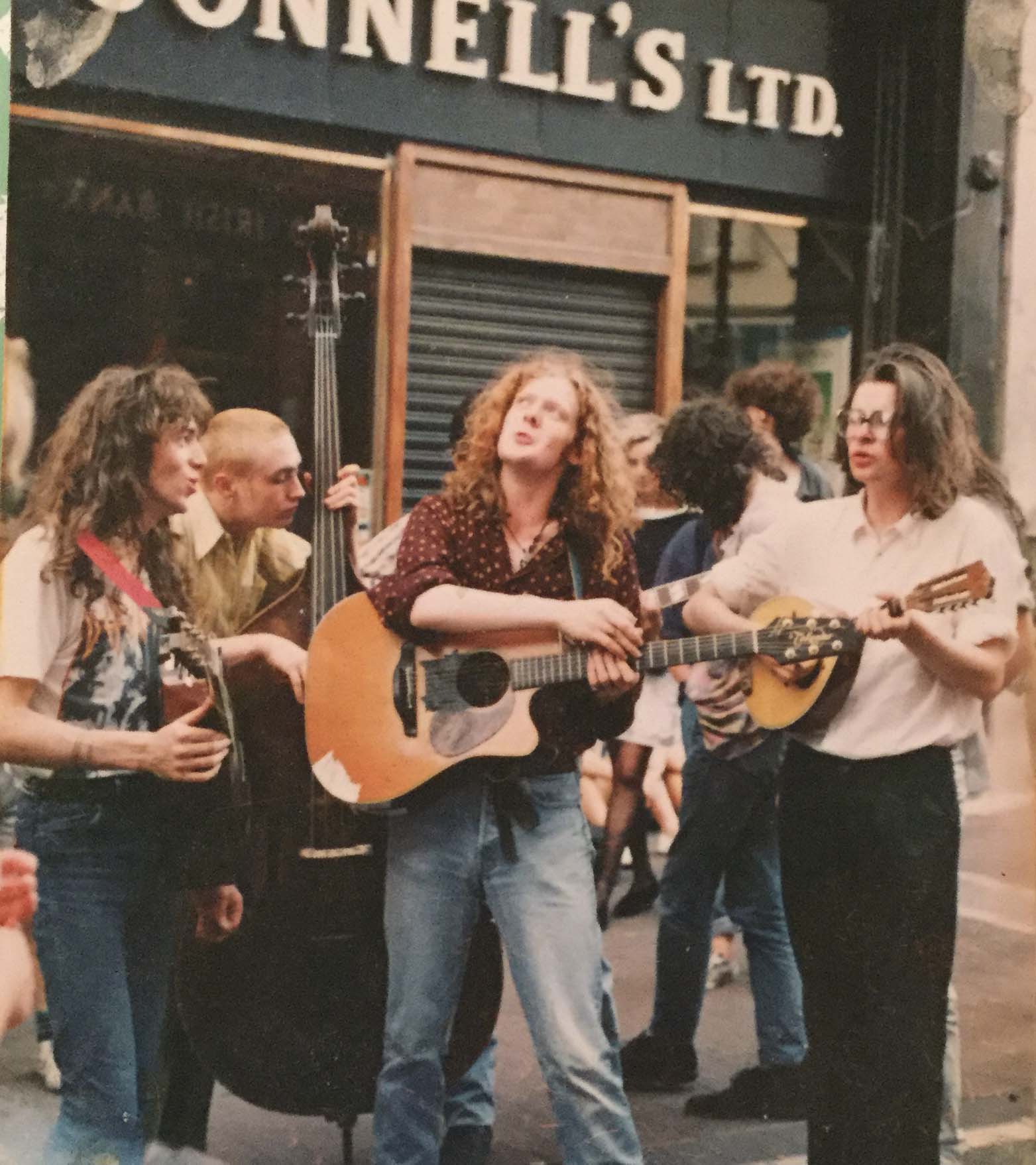

He also served time on Belfast City Council, was the National Organiser of Ógra Sinn Féin and his party’s Director of European Affairs in the European Parliament in Brussels. He’s also worked as a journalist and published several books. In the 1980s, he was a dreadlock-bedecked bassist with the band The Four Men, and has busked with Glen Hansard. During his short musical career, he dabbled in drugs, and told the Belfast Telegraph. “A lot of hash and weed would have been smoked, and at some point I am sure there would have been a little bit of speed. I was part of that culture… it’s not something I regret.”

A young Eoin Ó Broin

Ó Broin also says he was “very lucky” to have been born into a comfortable family “and at no stage during my upbringing did we want for anything.” In 1997, he had his collar felt by the Nordy peelers for climbing onto the roof of Belfast City Hall while protesting with Saoirse, the republican prisoners’ action group. He is widely – and rightly – regarded as one of the stars of the Sinn Féin front bench.

Sinn Féin is on a high, having become the biggest party in Northern Ireland, and leading opinion polls in the south. I wonder might that be hard to sustain until the next election down south?

“Unlike the other parties,” Ó Broin reflects, “many of whom only make contact with their constituents come election time, we knock on doors three times a week every week, so we do the groundwork well. I think we’re developing a reputation for having very, very credible alternative policies over a whole range of areas, from housing to healthcare to child care, as well as advancing Irish unification. I think that combination of ideas is succeeding.”

I have the impression that there’s a less strident tone coming from Sinn Féin.

“I don’t think it’s a question of being less strident. The thing we learned after the bad local elections of 2019 is that in opposition you have to do more than just express anger and frustration. You have to outline what would you do to make things better. Maybe it’s not so much a difference in tone – it’s about spending more time outlining what the alternatives are and how we would fix the problems created by 100 years of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael.”

Parties in opposition often seem to have all the answers, but when they get into power they frequently do no better.

“We’ve been quite unusual in this State,” Eoin says, “because we’ve had the same two parties leading government for a century with very little policy differences between them. We’ve had this bizarre situation re housing where Fianna Fáil, although propping up the Fine Gael government, were technically in opposition until 2020. But their policies were no different. So it’s no surprise that when Fianna Fáil took over the Housing area there was little change – and the few changes there were took us back to the bad old days of developer-led policies of the Celtic Tiger era. I do see a challenge for Sinn Féin, in that we have never had a government in this State led by a party committed to fundamental transformation of social, economic and constitutional realities. The capacity for that has been tested before, because of the Tweedledum-Tweedledee nature of Fianna Fáil-Fine Gael.”

Having played on the Dublin scene when The Frames were emerging, Eoin is friendly with Glen Hansard...

“We are,” he nods. “I was quite active in the Dublin music scene in the late ’80s and was a close friend of Mic Christopher too. The band I was in, The Four Men, played on a Rory Gallagher bill at the Mean Fiddler in London as part of Vince Power’s big Irish festivals around ’88 or ’89. We also supported Something Happens at the SFX.”

Pictured with Glen Hansard

At the Bob Dylan-Neil Young show in Kilkenny a couple of years back, Glen made a plea for a change of government. He also made the point we’d had either of two parties in power since the beginning of the State...

“You have to put those comments into the context of Glen’s increasing activism in the areas of Housing and Homelessness,” Eoin offers. “Glen isn’t a party-political person, and he wasn’t known for expressing political opinions. Like a lot of people he’s appalled by a wealthy country like Ireland having such a housing crisis. Today, the Irish Mirror is reporting another death of a homeless man on the streets of Dublin. I think that’s motivating him and driving his desire to seek political change. I think he’s right.”

Housing is a huge issue now. So what’s the bottom line?

“If Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael continue to control housing, then housing policy is never going to change. The recent Daft.ie report is the worst in five years. Rents are spiralling out of control. The number of rental properties available has plummeted by 77% over the last 12 months, and the government is providing far too few social houses and virtually no affordable rental or purchase homes. Without putting words into Glen’s mouth, it’s not that he’s just bored with Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, but like a lot of people he’s outraged that we have 10,000 men, women and children in emergency accommodation. We have the highest house prices and rent in the history of the State and virtually no public housing to meet people’s needs.”

LAND. MONEY AND RELIGION

Hot Press may be more concerned about this than others – but there’s a huge amount of land, in Dublin in particular, in the hands of religious orders and other Catholic church interests. I ask if it’s acceptable for them to drip-feed this onto the market and to make vast profits in the process? Would Eoin want to stop that?

“Yeah,” he says. “And there’s another story in the Irish Mirror today on the back of a parliamentary question I put a couple of weeks ago, that those religious orders that were to provide either cash or land from the most recent redress scheme (from which) over €200 million hasn’t been paid. But for me the single biggest thing that has to change is that the government must play a much bigger role in delivering large numbers of non-market housing. We have huge tracts of public land already available. We have 90,000 vacant homes across the State, maybe 20,000 vacant homes in Dublin. So not only do we need to build far more public homes, but it’s cheaper and it’s quicker and more climate-efficient to acquire existing structures and renovate and bring them back into use. So the religious lands is part of it…”

I’m curious about the so-called charitable vehicles that are used by religious institutions to avoid paying Capital Gains Tax. Would Eoin change the law to ensure that all religious interests would pay CGT on the sale of land?

“This isn’t something specific to religious organisations,” he points out. “The use of various forms of trusts or vehicles for the legal avoidance of Capital Gains Tax is a problem and needs to be addressed. Probably the most egregious example of this is our Real Estate Investment Trusts and other institutional investors. The legislation that was introduced in 2013 for those explicitly exempts them both from tax of rental properties and from Capital Gains Tax.

“We’re very clear,” he adds. “There’s no set of circumstances where a corporate entity that is engaged in real estate transactions and land development or residential development on a commercial basis should be exempt from CGT. There’s exemptions for young people selling a family home to buy another, that’s all fine. Commercial entities, whether they’re Real Estate Investment Trusts funded by the national pension fund or the property holdings of religious institutions – which are essentially commercial properties – should be subjected to the full rates of CGT. But what I would say first is that those religious orders who still owe government either cash or land for the redress schemes need to pay up.”

I don’t understand why they aren’t made to pay up, in the same way anyone has to, if they owe taxes to the State.

“That’s my point exactly,” he says. “My parliamentary question was intended to force the issue onto the agenda. The other issue is that there are large volumes of public land in the hands of local authorities. My own local authority has significant tracts of land. Public agencies such as the HSE or others have land lying vacant. So we need the government to increase capital investment with local authorities. But you’re right about money owed to the State by religious orders. They should be forced to pay it.”

People will be wondering if – in Government – Sinn Féin would force them to pay what they agreed to pay?

“Yeah. Absolutely. My view is they entered into agreements to pay. You would have to go back to look at the legislation and ask if the legislation needs to be changed to force those payments, but those agreements should be honoured.”

Whether interest could be charged at the usual punitive rate would depend on the detail of the existing legislation...

“I’d have no hesitation at all in arguing for that,” he says. “Keep in mind, the redress payments that were agreed were very modest, particularly given the land holdings etc. In fact, my preference would be, because land is such a valuable asset, if the land that was residentially-zoned, I’d prefer to see land instead of cash because the value of the land to the public is far, far greater than any amount of money.”

He makes the point that from now on, every government is going to be judged on housing.

“Even if the government meets its targets it’s nowhere near enough,” he says. “We haven’t a single affordable home to purchase delivered for a decade. We had 65 affordable homes for rent delivered last year. Any party that presides over a worsening housing crisis will lose seats in the election afterwards.”

A lot of land was given to religious orders to carry out charitable activities that have long since ceased. There’s something immoral surely in those orders trying to profit hugely by selling that land?

“Where I live in Clondalkin village, the Sisters of Charity had a wonderful convent building on a large tract of land. It had been gifted to the parish centuries ago by landowners but for the use of the public. Of course, their congregation is dwindling. The Sisters in their wisdom engaged Bartra (a privately-owned property company) to develop a really large commercial nursing home, which we don’t need in that area as we already have two or three – and where we need other things, like community facilities, housing etcetera. The local community led a huge campaign to try to get the religious order to withdraw from the deal with Bartra and sit down with the community to discuss what is really community land. All of the political parties supported that campaign. Yes, the community doesn’t own it. It was gifted to the parish. But surely we could have a dialogue around the best use of it, including if the Sisters needed some of the land on which to house their elderly sisters. That would be fine. But they wouldn’t meet us and the nursing home is now being built.”

CPOs AND THE NATIONAL MATERNITY HOSPITAL

There was a strange schemozzle in the Dáil a couple of weeks back when a Sinn Féin motion calling on the Government to secure full public ownership of the National Maternity Hospital was passed – but had no effect because it was ‘non-binding’...

“The National Maternity Hospital is another classic example,” Eoin reflects, “where a religious institution should have done the right thing in gifting that land for the State’s use, to ensure that the NMH would not only be publicly-funded, but built on publicly-owned land. Instead they’ve entered into this byzantine contractual arrangement to retain ownership of the land, therefore not only having clinical influence over the hospital but also ownership of the asset itself.”

It baffles me why the Government didn’t use a Compulsory Purchase Order to acquire the land for the National Maternity Hospital.

“Compulsory Purchase Orders are used regularly by government when they want access to land for roads, or to bring back derelict properties into use. We keep asking: ‘Why during the negotiations over the last nine years didn’t you ask the owners of the land to gift it to the State?’ I’ve listened very carefully over the past few weeks to Micheál Martin but he’s never answered that. They could easily have threatened the use of a CPO.

“We see really egregious examples of the State entering into long-term leases with private developers at enormous cost to the taxpayer and without lifetime security of tenure for social housing tenants. You could ask them, ‘Why did you enter into that complex and expensive lease agreement? Why didn’t you just buy?’ If the owner didn’t agree to sell then you threaten a CPO.”

National Maternity Hospital

I wonder if Sinn Féin would use Compulsory Purchase Orders in such situations?

“Absolutely. Without question. One thing we’ve said in our housing policy is that we would like to see an average of 20,000 new homes built every year for at least five years. At least 20% of those would have to be from existing buildings. It’s quicker, cheaper and more climate-efficient. Some would require CPOs, some merely the threat of a CPO, and some just negotiation.”

The approach of the Church to land ownership and use is something that needs to be highlighted more effectively.

“I remember having a conversation,” Eoin says, “with a senior director of development in a Dublin local authority who was responsible for managing the local authority’s land-banks. I remember him saying very clearly that the people who employ the best lawyers drive the most aggressive strategies in terms of land acquisition and land maintenance, and they’re the religious orders. But they only do that if government allows them. Go back to the redress scheme. I don’t think government has done anything to ensure that those religious institutions have met their obligations. But if organisations have entered into agreements to provide funding, that should be enforced.”

Sinn Féin’s plans to tax unused land might become very relevant here.

“We would tax unused land and vacant properties,” he says, “to dis-incentivise people sitting on it or hoarding it or, as you say, drip-feeding it into the market. We do have a bigger problem in our cities and towns with vacant properties that are simply being left for speculative purposes. If you walk, for example, into Blessington Street (in Dublin) or George’s Street, you’ll see whole blocks of beautiful buildings left idle. That’s prime real estate. Those buildings are structurally in good condition, if not necessarily ready to move into now, and they’re sitting on those properties effectively cost-free. Hoarding property and land during a housing crisis is like hoarding food during a famine. It should not be allowed.”

How would Sinn Féin deal with that?

“With property taxes, effective vacant land taxes, not the vacant land levy we have at the moment, and there would be supports to ensure that if you inherit an old property you could effectively bring it back to use, or rent it or sell it or give it to the Council for social housing or whatever.”

That could make a huge difference when there’s over a thousand families in emergency accommodation.

“The bulk of whom are in Dublin,” he says, “where we have 20,000 vacant properties. Some of them are three or four years in emergency accommodation which has huge psychological and health impacts on them and their children. There’s something obscene that, in a country with money and with properties, the government won’t take the necessary action. If there are people who have land that is residentially zoned, that land can and should be used for housing. And the same applies if there are vacant properties, whoever owns them, whether it’s a religious institution, a charitable institution or a government agency.”

THE IMPACT OF CUCKOO FUNDS

Religious orders, of course, are not the only offenders in relation to hoarding land...

“Land and the Church is an important issue, but we have a much bigger problem in Irish society,” the Sinn Féin man says. “Like land holdings by NAMA, private investors and institutional investors. As part of that – because when it comes to land and the Church, religious institutions are operating as commercial entities – what we need to make sure in our public policy is that private land, whether it has been granted the gift of residential zoning or planning permission, is used appropriately. The biggest tracts of unused residentially-zoned land are in the State’s hands. There should be punitive taxes on those properties, not to raise revenue but to force those properties into use.

“A lot of the land that religious institutions currently own is not zoned for housing,” he adds. “One of the really interesting things in the recent Dublin City development plan and the Dun Laoghaire development plan, is that some religious institutions did seek for that land to be rezoned as residential and they were refused. I think that was a good thing, because if you just rezone it you give the owner a huge uplift in its value.”

He argues for a pragmatic approach to the use of land owned by different State bodies.

“My strong view is, in the first instance, public land should be transferred from one public agency to another, like lots of HSE land. There’s also public land that’s not being used right. Take Donnybrook Bus Station. It’s in the wrong place for a bus station in the 21st century. Our buses now run from one end of the city to the other. Pearse Street Bus Station is exactly the same. These are huge prime sites for good quality residential development. So the State should step in and negotiate arrangements with Dublin City Council for a land swap, say, for a new state-of-the-art garage on the other side of the M50 and transfer those two pieces of land to Dublin City Council.”

Eoin believes that big mistakes were made after the banks collapsed that have fuelled the rent crisis.

“One of the big shifts in recent years is the arrival of the big international institutional investors, the vulture funds or cuckoo funds,” he observes. “Tax legislation was introduced by Michael Noonan (former Fine Gael Minister) whereby institutional investors not only pay no tax on their rent roll, but they pay no Capital Gains Tax when they sell their properties. We’ve created this system whereby very, very powerful global financial interests are able to enter the Irish market, and pay way over the odds for residentially-zoned land. They inflate the value of the land, which then inflates the all-in costs of the development units, making them much more expensive.”

By way of example, he cites the Johnny Ronan group.

“Structured as one of these institutional investment groups, with international investment finance, they paid about 25% above the guide price for the Poolbeg Strategic Development Zone, with about 3,800 homes to be built there. The cheapest units they’ll deliver there will be half-a-million euros and the upper end will be €650,000. There’s a legally-binding commitment regarding that zone, agreed by Dublin City Council unanimously with the community, that there should be about 550 affordable, purchase homes there. There’s no way in hell you can deliver that.”

What’s the definition of affordable?

“I have a very clear definition,” he insists. “You start by asking who are the people who are not eligible for social housing. You look at their income. They’re generally people whose gross income might be about €40-45,000. There’s a general rule of thumb of affordability is about 30% of net take-home pay. My view is that it should be a bit lower than that, maybe down to 27% or 28%. The rent for a 1, 2 or 3-bedroom home would then be about €700-900 a month and for purchase for anything from €180,000 to €250,000.”

THE NATIONAL MATERNITY HOSPITAL AND MENTAL RESERVATION

The government has decided to press ahead with plans to co-locate the National Maternity Hospital with St. Vincents. But there are still fundamental problems with the proposition – and a number of hurdles to be crossed. Eoin Ó Broin asks a simple question that is also troubling campaigners for a fully publicly-owned hospital ...

“People cannot understand,” he says, “if the Sisters (of Charity) said initially that they wanted the land to be a gift to the Irish people, why don’t they gift the land to the people? The government is using tactics to say this will delay the hospital by 5 or 10 years, and Holles Street Maternity Hospital isn’t fit for purpose and we need a state-of-the-art maternity hospital for Dublin. We don’t want this delayed. But if Micheál Martin is telling the truth, that a 299-year lease at a tenner a year is effectively public ownership, then just gift the land to the State?”

Given their failure to keep their word in relation to redress, would Sinn Féin trust the bona fides of the religious in relation to the National Maternity Hospital?

“Our position has been crystal clear from the start of this,” he says. “We want that land in public ownership. We want the National Maternity Hospital in public ownership and we want to ensure that all of the legally-permissible maternity services, and other legally-permissible gynaecological services, are provided in that hospital in perpetuity. So owning the land is the best way to guarantee that.”

Hot Press has called on the Government to insist on the publication of all of the correspondence between the Religious Sisters of Charity and all of the other religious interests, either lay or secular – including the Papal Nuncio.

“We have already called for it,” he says. “Sinn Féin spokesperson on Health, David Cullinane, before the meeting last week of the Cabinet that was going to make a decision on this, called for all of the documentation to be published and be made available to the Oireachtas Health Committee and for the Minister to come in and be scrutinised on it. Because there was some concern from some women members of cabinet, the government deferred their decision. They published some of the documentation, and that documentation has caused some increased concern. For example, it has the phrase, ‘all legally-permissible and clinically-appropriate services will be provided.’ But there’s no definition of ‘clinically-appropriate’. You also have this business about the default increase in the rent from €10 a year to €850,000 a year, which has caused a lot of concern as well. We want full transparency, full accountability, but more important than that we want the land gifted to the State.”

Hot Press has made the point that the real problem is that Church representatives believe they answer not to the State, but to the higher authority of the Vatican – and that the doctrine of mental reservation allows them to say one thing and then do whatever they consider in the interests of the Church or the religion...

“I have no idea. I’ll be very honest, I’m an atheist. I have very little time in my life to ponder questions of other people’s theology. I’m trying to find solutions to the housing and homelessness crisis. I’m far more interested in addressing the pressing issues for my constituents. I don’t understand the question so I won’t try to answer it.”

What about the argument that there was an element of Mental Reservation in the way Sinn Féin politicians dealt with sexual abuse within the ranks of the IRA – for example in relation to Máiría Cahill?

“First of all, I know Máiría Cahill personally,” he says. “We were in Sinn Féin Youth together and I’ve met her on many occasions. I’ve publicly said that republicans could have done much more to ensure that her experience of sexual abuse and the aftermath was dealt with in a more appropriate way. The challenge, I suppose, is that Máiría Cahill came forward at a time when we were still at the tail end of an armed conflict. The relationship between the police and the wider republican community was still enormously problematic. The types of procedures that are thankfully now in place in SF and society in general in the North, in terms of a relationship with the PSNI, weren’t there then.

“That doesn’t excuse or justify Máiría's experience,” he adds. “I think we could have done much better, and I think we’re in a much better place as a party and society. That’s in part due to people in SF and other places who tried to bring about an end to the conflict and create a more normalised, peaceful society. There are many parts of the conflict which, with the benefit of hindsight, on reflection, we could have all handled better. That’s definitely the case in terms of Máiría Cahill’s experiences.”

Officially, the IRA has been disbanded – is the memory of the connection between Sinn Féin and the IRA always going to be there to haunt everyone in the party?

“I don’t see it that way,” he says. “If you take my own constituency, myself and Mark Ward took 40% of the vote. Lots and lots of the people who vote for us didn’t support the IRA, and didn’t support Sinn Féin’s political position during the conflict in the North. They know where we stood then, they know where we stand now in the context of the Peace Process. But they vote for the party, and I think that’s because Sinn Féin has rightly got recognition, along with others, for the part we played in bringing the conflict to an end and for the peace we now have. I also think the overwhelming majority of voters are voting for the future and not for the past. I think we’ve convinced people that whatever one’s views of the conflict and Sinn Féin’s political positions during that period of time, or the relationship then between Sinn Féin and the IRA, people are voting for the party because of what we’re proposing in terms of political, economic and social change into the future.”

ON THE CALL FOR A BORDER POLL

There is a concern that if we push too hard now for a united Ireand, we might end up with some kind of a bloodbath. If that were to begin, it’s be hard to see the IRA not re-emerging in some form.

“I don’t see any set of circumstances in which the IRA will re-emerge,” he states. “The IRA no longer exists. We had a peaceful transition into a new political dispensation. I don’t see a bloodbath is likely to happen. I lived in North Belfast for 11 years in an area that was heavily controlled by the UDA, so I appreciate more than many people the depths of support for the Union among a wide range of people in the North and legitimately so.”

He emphasises that Sinn Féin don’t want to impose anything on anybody, or generate or create further levels of conflict.

“If there is going to be a United Ireland, and I passionately believe it would be better for people North and South, how we get from here to there is through dialogue, through persuasion, and through a democratic process where no matter what the outcome is, we’ll accept it. I think that’s possible. So it’s not that I am naïve about the potential disruptive effect of small groups of loyalists who are still involved in paramilitary activity. But some people of a certain age will remember the loyalist opposition to the Anglo-Irish Agreement being able to bring the State to a standstill.

“Those days are gone. What we have to do, to move from where we are today to the point where we get a referendum, is to engage with people, and say, ‘OK, if you don’t want a United Ireland, but if it were to happen, how do we make sure that your social, your economic and your political and cultural rights are fully protected, that you don’t become a minority or feel that it’s a cold house either for unionists or others?’ If there’s a referendum and we lose it, Sinn Féin will accept that. Of course we’ll continue to argue our case, as the Scottish National Party does (having lost their independence referendum). But if it’s open and transparent and democratic, I think that limits the possibility of violence.”

Does he really believe that we can rule out the possibility of violence on the loyalist side?

“Obviously I can’t speak for loyalism, but what I can say is, for example, with the protocol and the negative fallout from Brexit, we’ve had all sorts of threats from loyalist politicians – but the actual level of violence from those connected with loyalist paramilitarism has been very small. That doesn’t mean it’s not significant – in fact it’s predominantly affected loyalist communities themselves. Of course you have to factor that in and deal with it. But we have to engage with those communities, and with their community and political representatives. We have to ensure that there’s a public debate, and people have to feel that they are included in all that. “But ultimately, if we’re democrats, we have to accept the outcome. That’s not to be triumphalist about it. I was elected in a North Belfast that saw a quarter of all fatalities that occurred as part of the conflict. I was there during the loyalist blockade of Holy Cross School (in the Ardoyne area), so I’m not in any way naïve about those kind of realities. But I do think it’s possible to design a democratic process where the overwhelming majority of people should be able to accept the outcome.”

Does he welcome the growth of the Alliance Party?

“Yes. For me it’s a really exciting thing. I know there’s been a big debate about it, but Belfast City Council just appointed a new Alliance Party mayor and he opened his speech in Irish! He’s not a Gaelgoir. He doesn’t come from a nationalist background. He’s from East Belfast. I was a Belfast City Councillor for the first election when the unionists lost their majority. We had a phrase which we used from then on, ‘Belfast is a city of minorities’. And that’s a good thing, because minorities have to work together. I think the growth of that other space, as we call it, means there’s a growing number of people who are open to all sorts of conversations about a whole lot of things.”

Belfast City Hall

He mentions an opinion poll recently that asked Alliance voters, if there was a referendum tomorrow how many would vote – for unification, for the union, or were ‘don’t knows’.

“They were split three ways,” he says. “So any signs of people being willing to open and explore other options is a good thing. I see it as a huge opportunity for us. But I also see it as a sign of the North itself moving forward.”

Some people would say very slowly...

“One of the lessons of the last 20 years is that it would be a mistake to see things as monolithic and never open to change. I always use this analogy. Look at the very ornate late 19th century tombstones in Belfast Cemetery with inscriptions like “The Very Reverend William Bingham – Loyal servant of the Queen – Proud Orangeman and true Irish patriot.” There was a moment in time when unionists, a little like for Scottish folks, were able to combine their sense of Irishness with a sense of loyalty to their cultural traditions and their attachment to the monarchy. Obviously from the end of the Home Rule period through independence and partition, all of that changed. But cultural identities and constitutional affiliations are not fixed forever. It’s all about persuasion, it’s all about dialogue, it’s all about convincing people about the merits of one course of action over another. People’s views change. If we are to secure Irish unification, we have to do more than convince some others. We have to convince as many people as possible. Clearly, a 50% plus 1 referendum is a democratically-valid vote, but 60% is better for its democratic integrity and stability.”

Whither the DUP after the recent election – and their refusal to participate in forming a Government?

“Jeffrey Donaldson had a very bad election. But the seats he lost weren’t won by Jim Allister and the TUV. They were won by the Alliance. And I think the lesson for Jeffrey Donaldson is that people want the Assembly up and running. No matter what our differences are on the constitution, people want politicians working together on the two big issues facing the North at the moment: the cost of living and the health crisis. I think if Jeffrey Donaldson and the DUP continue to delay the restoration of the Assembly, particularly as those two big issues deepen, if there’s another election, I suspect an even larger number of small u-for-unionist voters – people who just want to get on with their lives – will punish the DUP for their failure to do what they were elected to do.

“Ultimately, people want good employment,” he adds. “They want affordable comfortable housing, a good health service that works. They want their kids’ lives to be better than theirs. That’s where the North is moving.

Historically, Sinn Féin is identified as Catholic nationalist. Does the party need to disentangle itself from the notion that you’re somehow connected to that Catholic background?

“Sinn Féin doesn’t have any connection to the Catholic Church any more than we have a connection with all faith-based communities. In fact, they’re our biggest critics and have been for the last 30 or 40 years, whether it’s our position on abortion or whatever. They’re still critical of us from the pulpit. It has had no impact on our electoral success. We’re very clear that all government policy treats everybody equally, irrespective of their religion, cultural background, race, gender or class.”

North and South, Sinn Féin were slow to support a woman’s right to choose.

“We were slow in relation to taking a very strong position on reproductive rights. On women’s rights, Sinn Féin were probably far ahead of most parties in relation to having gender quotas. In the recent election, 56% of our elected representatives are women. But you’re right: as long as I’ve been in the party, there was a group of us who were pro-choice, and some, such as Peadar Tóibín who left the party, were anti-choice. The people in the middle were probably more reflective of Irish society in general. I think the role we played in the referendum on the 8th Amendment was really positive. I think the party ended up in the right place. I’m very comfortable with that.”

So is the party committed to a secular society both North and South?

“Yes. Government legislation and policies and public services have to be provided to all people equally. There are big challenges to that both North and South. Education is probably the biggest challenge in terms of denominational control and negotiating a way into a system where parents have real choice in non-denominational education. When Martin McGuinness was Minister for Education (in the North) he was enormously supportive of integrated education to ensure that parents had that choice. We’re very, very supportive here (in the South). But we have to recognise that large numbers of parents want to send their children to denominational schools. That is a challenge. For me, the best way is to give parents choice.”

Are there any aspects of policy that would have to be treated differently in the South compared to the North?

It’s not that aspects of policy would have to be treated differently. The key issue is that the North doesn’t have revenue-raising powers and the North currently doesn’t have the kind of legislative powers we have in the South. Therefore, achieving some of the objectives we want to achieve islandwide is not necessarily possible through the same route North and South. So for me it’s like your question around education – it’s always about giving people choice and access to services irrespective of differences, religious or otherwise.

FAIL TO PREPARE, PREPARE TO FAIL...

There has been another curious shift recently, with Sinn Féin less vociferous in calling for a border poll. Or is that a mistaken impression?

“We’re not fixated on the date. Mary Lou McDonald made that really clear in interviews after the election. What we want is the preparation. A good way of thinking about it is this: a hastily-called referendum that is badly prepared for could be hugely divisive. Brexit is the best example of that. We don’t want a referendum like that.”

Mary Lou McDonald and Michelle O'Neill of Sinn Féin

Is that because you think it might not be passed?

“Whether you win or lose, English society in particular is deeply divided on the other side of a hastily-called, poorly-prepared-for referendum. Whereas if you look at Scotland’s independence referendum, it was a completely different arrangement, with three or four years of preparation, and detailed publication of research and documentation on what was mostly very reasoned and thoughtful argument and debate. A vote was taken and Scotland was no more divided the day after than it was the day before because everybody accepted it. For me, and for the Party, the most important thing is to get the preparation right, then you can work out the date. Besides, we don’t get to set the date. It’s the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, unfortunately, who does that under terms set out in the Belfast agreement.”

So what can you do now?

“We can make sure that we do the groundwork. We think the Office of the Taoiseach, for example, could do far more. What are the vast majority of people going to want to know as part of this debate? What’s our health system going to be like? And our education system? What’s the tax regime going to be like? What are the protections for cultural identity and diversity? Most ordinary people are going to ask those kind of questions. So are we going to dissolve the NHS into the HSE? Will we have two parallel health systems with different rules? Or will we transfer both into a single system? These are big issues. I think the public will want a lot of research data. Two years before the referendum the SNP published a white paper, I think it was about 300 pages long, setting out their view on Scottish independence. Of course we would rather see it sooner rather than later, but right now the process is more important than the date.”

Given his absurd unpredictability, and his need for regular diversions from the chaos he creates, might Boris Johnson decide to call a poll now?

“Nobody ever knows what Boris Johnson is going to do, but I would be surprised if that idea was anywhere in his thought processes. A far more important thing would be for us to have an all-Ireland Citizens’ Assembly. I think we need an Irish Unity unit within the Department of The Taoiseach, producing all that research and preparation. I think we need at every level, from the informal, to the semi-formal, to the formal – from the local to the regional to the national – the promotion of those debates and conversations. For me, that’s really important right now.”

What about the view that Sinn Féin bringing up the issue of a poll destabilises politics in the North?

“What I’d say is that everybody has the right to advocate peacefully and politically for whatever political change they’d like to see. It should come as no surprise that Sinn Féin will continue to advocate for Irish unity as one of our core political objectives. And unionists arguing for partition doesn’t destabilise the nationalist community. Unionists have every right to campaign and advocate their case for the union. Of course they do. The whole point of the post-’98 settlement in the North is that everybody has the right and the entitlement and the political space to argue for how they would like the future of our country. We’re not trying to strongarm anybody, or shoe-horn anybody.

“Just imagine, when Hot Press were campaigning for a more liberal Southern state,” he adds “if somebody said to you, ‘Oh, be careful there, you might destabilise a section of Irish society that is uncomfortable with that’. I’m sure you’d have said, ‘I’m sorry, we have a democratic right to campaign for the future of our country, so long as we do it peacefully, democratically and respectfully’. So if unionists have a problem with us doing that, then I think unionism has a problem. We make no apologies for wanting a 32-county democratic socialist republic that treats all citizens of the nation equally.”

Sinn Féin are seen as being on the brink of government. What is the legitimate army of the Republic, to which you and members of Sinn Féin owe your allegiance?

“There’s only one army to the State, and that’s the Irish Defence Forces. Whether SF is in Opposition or Government, we recognise the Irish Defence Forces as the army of the State. There’s no question or concern about that. What I will say is that we had an armed conflict in this country for 30 years. We had almost a century on and off of conflict, particularly in the Northern state. Violence was for too long a feature of Irish society: violence by the British state, loyalist paramilitaries, republican groups. Thankfully, we’re not in that place anymore. I lived in Belfast for 11 years, I was an elected representative there during the final years of the conflict and peace process years. Thankfully, because of the considerable work of large numbers of people – often people who were directly involved in the use of violence or had experienced violence themselves – we’ve managed to build a peace process. Society is moving inexorably towards a transformed future and that’s to be welcomed.”

Does Sinn Féin owe any allegiance to the modern, Provisional IRA?

“First of all, the Provisional IRA doesn’t exist. It was disbanded a number of years ago according to their own spokespeople. There is no Provisional IRA so the question doesn’t make a lot of sense. We’re in a post-conflict situation. We’re in a situation where thankfully, for the first time in the history of the island, since 1998 all sections of society can legitimately pursue their political aims through peaceful and democratic means. That wasn’t the case in the North unfortunately because of British government policy there. The only people I owe allegiance to are the electorate, who have given me the incredible honour of being a politician in my own constituency – and obviously to the party activists who work hard to help me get elected and return me to the Dáil.”