- Opinion

- 19 Oct 23

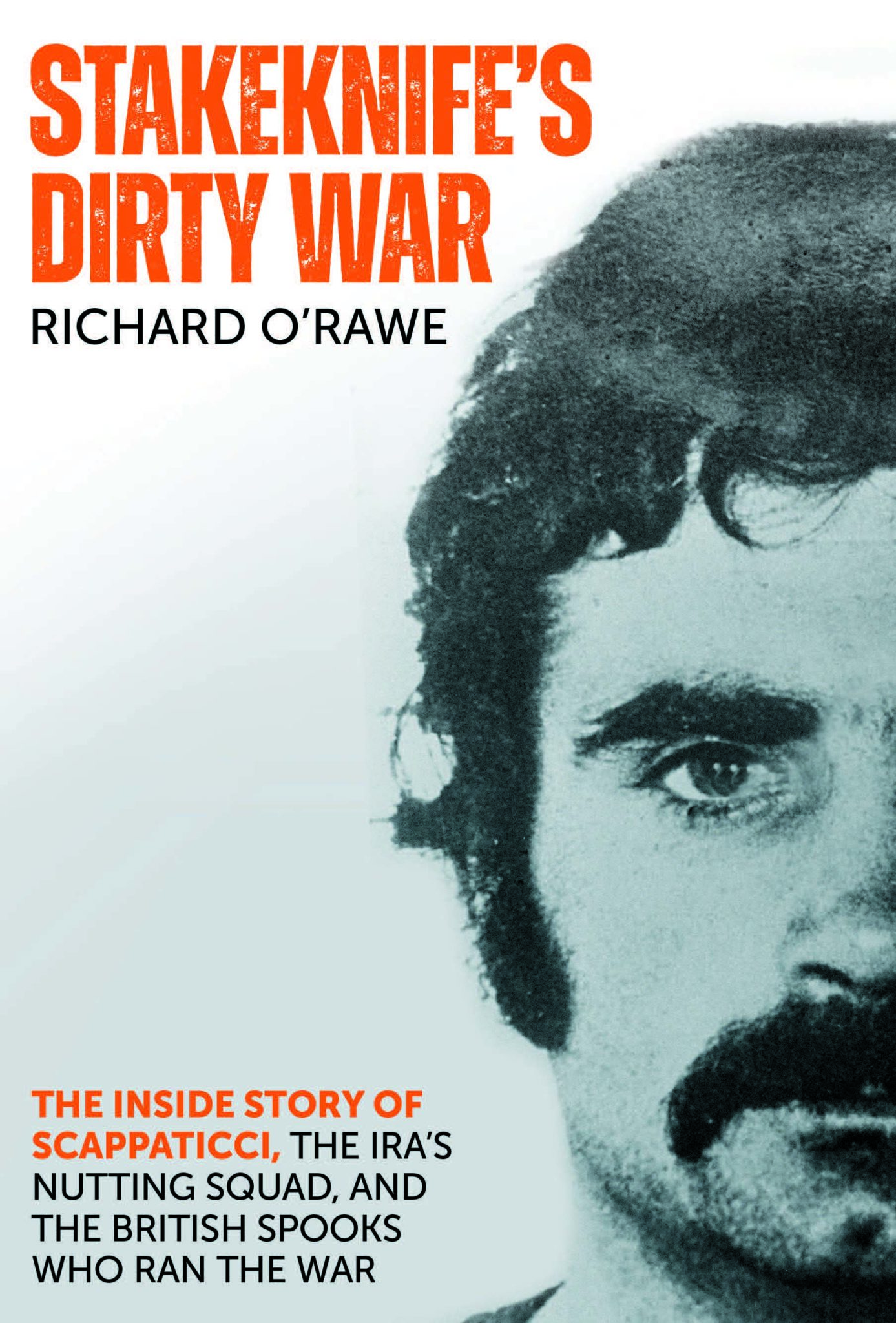

In his new book, Stakeknife's Dirty War, ex-IRA prisoner turned author Richard O'Rawe examines the story of Freddie Scappaticci, the one-time member of the IRA's so called Nutting Squad, who was sensationally revealed to be a British agent. And there may be more explosions to come...

Richard O’Rawe is a one-time IRA hunger strike prisoner turned bestselling author. In his new book, Stakeknife’s Dirty War, O’Rawe considers the strange case of the titular figure, Stakeknife, aka Freddie Scappaticci, a member of the IRA’s notorious Nutting Squad - a group of senior IRA operatives who had been tasked with rooting out, punishing and murdering informers.

In 2003 this top-level IRA insider was sensationally revealed to be a British intelligence agent.

Naturally, this carried all sorts of implications for the British government’s involvements in the Nutting Squad’s activities, which as yet remain unanswered. But all of that may change soon, with the release of the Kenova Report - commissioned by the PSNI and led by former Chief Constable JonButcher - into instances of kidnap, torture and murder led by Scappaticci and potentially colluded in by the “members of the British Army, Security Services or other government personnel.”

FEROCIOUS TEMPER

Advertisement

When did O’Rawe first meet Scappaticci?

”It was 1973 in Long Kesh,” he recalls in Dublin’s Brooks Hotel. “It was my second time being interned. When I say I met him, I was in cage three and he was as in cage four, and we were nodding acquaintances. That was basically it. I didn’t really know Scappaticci in the proper sense. And even when I got out, it was the same thing. I never had a pint with him or anything.

“I always thought Scap was a very solid IRA man. I’d been aware he’d been a very senior figure. He got out in March ‘73 after going in back in ‘71. He then went on to become Brigade OC in Belfast, the most important job in the city. So I thought of him as a very serious IRA man.”

Consequently, O’Rawe must have been shocked when the revelations about Scappaticci emerged.

”I couldn’t believe it,” he acknowledges. “He was eventually outed in 2003. and the whole of the North was absolutely knocked out. If you’d have said to me, ‘Who’s the last person you’d have imagined was going to be a British agent?’ I’d have said Freddie Scappaticci.”

Nonetheless, Scappaticci had something of a murky background, with allegations of domestic abuse and sexual violence. In the book, O’Rawe speculates as to what might have turned him into a British agent.

Advertisement

”There’s about six or eight different proposals, some of which I think don’t work,” he considers. “One is that he was involved in a major tax scam and that left him vulnerable to a long prison term. The other is that he was involved in a charge concerning a sexual encounter with an underage girl. Neither of those have been proven. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if it was the latter, and there was some sort of sexual element to it. But there’s no evidence.”

Didn’t he end up in prison for possessing extreme pornography?

”He didn’t end up in prison,” O’Rawe in corrects. “In 2018, the Kenova inquiry into Stakeknife raided his home and they lifted a video, on which there was something like 340 images of pornography involving animals, and he ended up in court for that. He got a fine. He was watching bestiality on his computer.”

O’Rawe speculates in the book that blackmail may have been what turned Scappaticci.

“With the likes of Special Branch, their currency is blackmail, that’s how they operate,” he says. “If they catch you with a gun, they say, ‘We charge you and you get six years, or you come work for us’. I think Scappaticci was too strong an IRA man to be a walk-in, and I don’t think he went in for revenge. I think his motivation was blackmail - in some form or other, that got him working for them.”

Psychologically, he seems to have been a particularly twisted character, with O’Rawe noting his ferocious temper - and his sly, somewhat deranged viciousness.

”His favourite trick was to put a brick inside a sock and batter you over the head when you weren’t expecting it,” he says. “If you crossed him, you wouldn’t have known a fight was going to start. He’d hide the brick behind his back, then when you were looking the other way, he’d go over and smash your head in.”

Advertisement

NUTTING SQUAD

At the time, did you feel the activities of the Nutting Squad were necessary?

Advertisement

“I have to tell you straight,” says O’Rawe. “At the time, I didn’t give it a good deal of thought. When I was an IRA volunteer, I believed - just like Michael Collins - that informers and spies deserved to die. It never crossed my mind to even question that, and I don’t think it crossed any republican’s mind.”

So there was nothing throughout this long period to indicate Scappaticci was a British agent?

“Well, you have to refer back to South Armagh,” says O’Rawe. “He was questioning a suspected informer there, an internal security guy called John Joe Magee. They broke him and he was just waiting to be executed. Scappaticci did the first thing he always did, phoned up his (British security) handlers and said, ‘This guy’s going to get shot dead, he’s in such and such a house.’ But the cops hit the wrong house.

”South Armagh fellas are very sharp. They’ve got their wits about them, and they didn’t like the line of questioning that Scappaticci was taking. They sent word up to Belfast - and they just ignored it. Scappaticci just went on as he had before.

”He was totally trusted. He was on the court of inquiry into the Loughall massacre. There was talk he was on the court of inquiry into Gibraltar, when three volunteers were shot dead. There was talk he was suspected in 1991, but nothing happened.”

The chaos being sowed by the British government was incredible.

”It only looks like chaos,” counters O’Rawe. “When I started the book, I had no idea what I was getting into. I knew Scappaticci was dirty, everybody did, but I had no idea about the UK's Tasking and Co-ordinating Group. Every time he gave them an opportunity to intervene, and save that person’s life, they didn’t do it. I didn’t know how dirty the British government was. I knew the IRA was totally infiltrated, but I had no idea how utterly filthy the whole of them were.

Advertisement

”I mean, I was a fucking idealistic IRA volunteer. I had no idea this other world of espionage and fucking subterfuge was so prevalent, and that innocent people were being killed and sacrificed, to make sure other people had positions of power. The British government was running everything.”

Do you feel any regret over the republican struggle?

“I regret the whole thing, that there ever was a struggle,” says O’Rawe. “The struggle didn’t work. We still live in Great Britain! The struggle was actually unfinished business from 1921, from the War of Independence and the North being left out of the republic, or the Free State as it was then.

”The nationalists in the North were treated like shit by unionists. The whole fucking State was gerrymandered to make sure there would be perpetual unionist control. Nationalists never had the levers of state, they had no representation or constitutional way forward.”

HIGHLY CONTENTIOUS

Advertisement

What about the argument that the North is now a more equal society, less oppressive to republicans and Catholics?

“The reality is there are more Catholics now in the North,” he says. “Nationalism can only grow. The time will come when it will grow to such an extent, there will have to be a referendum. I think the south has come back to its nationalist roots in many ways, and that’s a good thing. But we’re going to see it all through non-violent means. There’s no room for armed struggle.

”Because I was part of it, I can understand why it was so attractive in 1969. There being no alternatives, you say to yourself, ‘Well, first of all, the Provisional IRA was a defence force, it wasn’t an attack force’. But the more oppressive the British became, the more the IRA responded, so there was a cycle. And I was okay with all of that. But at the end of the day, the armed struggle didn’t work. We’re still part of the UK, it failed.

”I do not applaud failure, and therefore I am sorry there was ever an armed struggle.”

In the book, you examine the highly contentious question of whether Martin McGuinness was working for British intelligence.

”It’s very prevalent among IRA people,” says O’Rawe. “Ultimately, I don’t think there’s enough evidence to say it. That’s a different thing to saying, ‘I don’t think he was an informant’. In the book, I write about Frank Hegarty, a Derry informer who McGuinness cultivated. He brought him up to the position of quartermaster, which is very damning of McGuinness. This guy, Hegarty, had been in the IRA and was dismissed because he was going with a UDR man’s wife, and he was a suspected tout.

“Then he came back and McGuinness absolutely embraced him, which he should never have done. The IRA in Derry were going fucking spare that this guy was back in play. Hegarty went from being a private to virtually top of the tree in terms of the IRA staff structure.”

Advertisement

Did you like McGuinness?

“I didn’t know him.”

But did you like his public persona?

“I did, aye,” says O’Rawe. “The book isn’t so much critical of him, and I’m not critical of him. I lay out the facts and let the reader make up their own mind.”

But surely he would have been a total failure for British intelligence, given what he did for the cause of republicanism?

“Not if you’re undermining the struggle at every chance,” he says. “It’s like two faces. One is saying armed struggle is the only way forward, and the other is saying, ‘You’re not allowed to work on operations unless I say so’. It’s the spying game again. I don’t know if you’ve seen the tape, The Secret Army. There’s McGuinness putting a bomb into a car, and he’s showing kids in Derry guns. That tape was sent to London to be processed every night.

“MI6 was checking on those tapes to see if anything was of intelligence interest. There’s McGuinness, the OC of Derry, putting a bomb into a fucking car - that should have been 20 years. What happens? The tape disappears until after he’s dead. How does that work out?”

Advertisement

What’s the current Sinn Fein take on Scappaticci?

“They don’t say anything. It’s still very embarrassing that a guy of this calibre was turned. I’ve never heard Gerry Adams talk about it and Mary Lou’s certainly not going to talk about it. I’ve never heard anyone pass comment within the republican movement.”

POLITICAL NOUS

It’s a mad story.

”It’s a fucking crazy!” O’Rawe says. “The point is, this is only the start of it. In October, the Kenova report’s coming out. If he backs up what I said, that Scappaticci told his handlers beforehand, the place will go nuts. The political fallout will be enormous.”

Advertisement

I remember the Guardian’s late Northern Ireland correspondent, Henry McDonald, saying he found Gerry Adams psychologically unfathomable. What’s your take on him?

“Big Gerry’s a strange guy,” says O’Rawe. “There are traits that he shows at times which some people refer to as ‘sociopathic’. Sometimes he’s nutty. He talks strange and all that. And sometimes he shows great political nous. He’s a conundrum. A lot of (IRA) people didn’t talk to me after Blanket Men. Adams never stopped talking to me.

”Me, my wife and two kids went to Shane MacGowan’s 60th birthday party in the National Concert Hall. I didn’t know Adams was behind me, and the next thing he says, ‘Hello Richard! How are you?’ He talks to you, and I get on okay with him. But who’s the real Gerry Adams?”