- Opinion

- 20 Jan 23

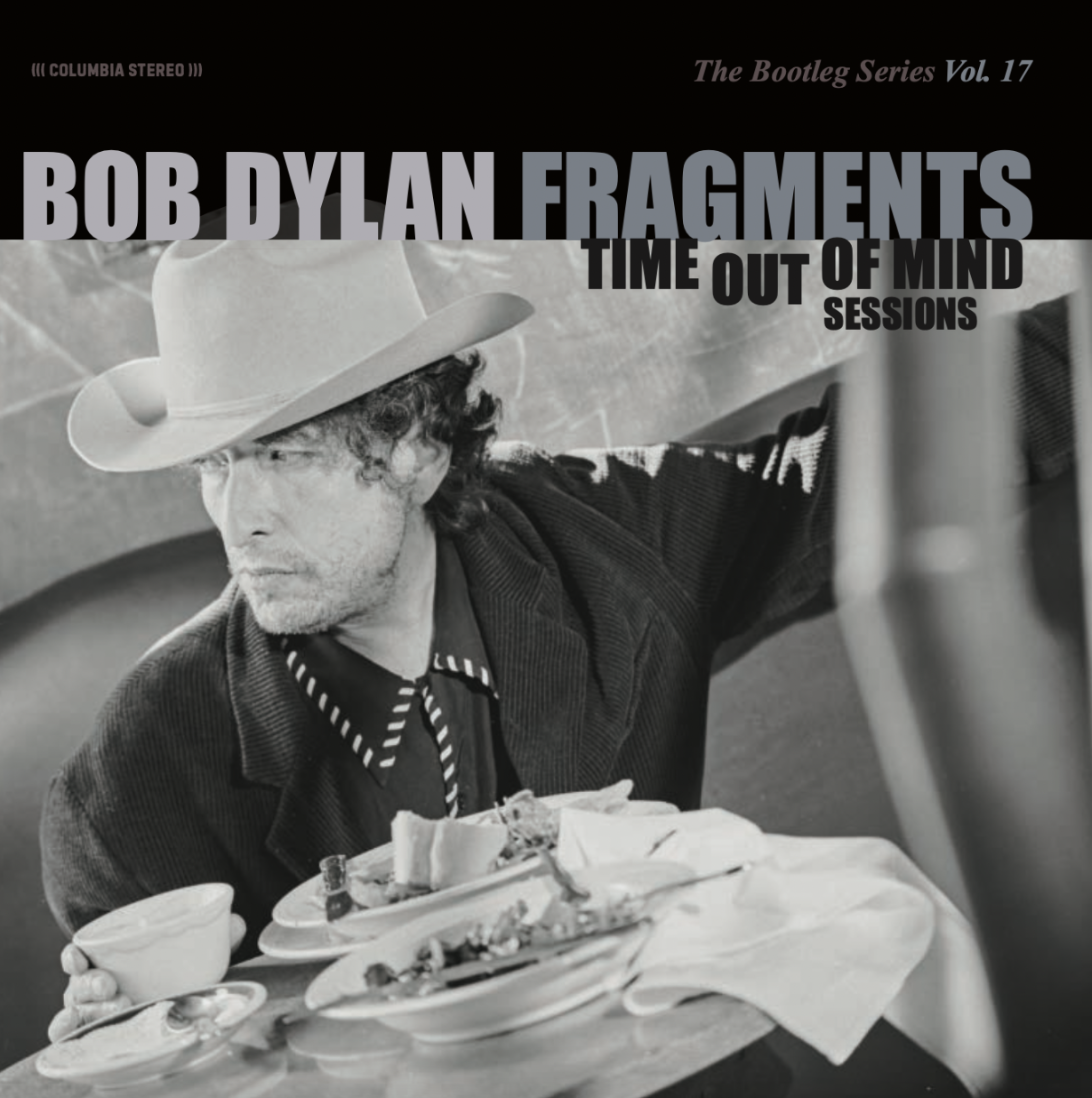

Exclusive Review: Bob Dylan’s Fragments – Time Out of Mind Sessions 1996-1997

Hot Press takes an exclusive, detailed first listen to the extraordinary Fragments, Bob Dylan’s new release in the “official bootleg” series – which casts fresh light on the very process of songwriting.

….his predecessors from time out of mind had always customarily carried the wand….

—Parliament Rolls of Edward I, C49 69 (1302)

It means before memory. Time out of mind is the time people cannot recall, of which there is no oral or written record, of even pictographs on cave walls cannot enable those living, even centuries later, to look back and say yes, I remember.

Once upon a time, not out of mind but long ago, now, Bob Dylan starred in a movie called Don't Look Back. On his 1997 record Time Out of Mind, he kicked that concept to the curb and revelled in retrospect, returning to the ballad form he’d long loved (‘Not Dark Yet’ and 'Highlands’), stricken blues ('Love Sick’, ‘Dirt Road Blues’ and ‘Till I Fell In Love With You') and the 1950s rockabilly rock and roll he was raised on as a boy in Hibbing, Minnesota (‘Million Miles’ and ‘Cold Irons Bound’).

Time Out of Mind was Dylan’s first record of original songs since 1990 and his first double album since 1975, thanks largely to the near-seven minute length of several songs and the 16 and a half minutes of ‘Highlands’. It was awarded the GRAMMY for Album of the Year, Best Contemporary Folk Album, and for ‘Cold Irons Bound’ Dylan won for Best Male Rock Vocal performance. In the twenty-five years since its release, Time Out of Mind has risen to and remained in many listeners’ lists of top Dylan albums, and is generally regarded as his brilliant comeback album after the critically dismissed decade and a half since Infidels (1983).

Fragments—Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997): The Bootleg Series Vol. 17 (January 27) is one of the most anticipated in Dylan’s “official bootleg” series. Not only does it contain new versions of the album’s songs, stripped down and remixed by Michael Brauer, and alternate versions of those songs, but studio outtakes of songs like ‘Mississippi' (one of Dylan’s finest, recorded for but not ultimately included on Time Out of Mind), a host of versions recorded live in concert, and some—both live and studio material—previously released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: Rare and Unreleased 1989-2006 (2008).

Dylan’s reminiscences of working with the Canadian-born musician and producer Daniel Lanois, recommended to him by Bono in the 1980s, on his 1989 album Oh Mercy are one of the most memorable sections of his autobiographical Chronicles Vol. 1, both because of Lanois and his methods, and the steamy dreamy New Orleans setting. Dylan’s character sketch of Lanois on a first impression is for the ages: “He was noir all the way — dark sombrero, black britches, high boots, slip-on gloves — all shadow and silhouette — dimmed out, a black prince from the black hills.” In concluding the chapter about recording Oh Mercy, Dylan wrote, “Danny and I would see each other again in ten years [eight, actually] and we’d work together once more in a rootin’ tootin’ way. We’d make a record and start it all over, pick up where we left off.”

Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.

Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.Dylan wrote and revised the songs for Time Out of Mind in 1996 and 1997, and drafted some with melodies under construction in 1996 in an old Mexican movie palace called the Teatro in Oxnard, California, with Lanois and two members of his touring band at the time, longtime bassist Tony Garnier and drummer Tony Mangurian. In 1997, for the album recording sessions at the legendary Criteria Studios in North Miami, Florida, many more musicians joined in: drummers Winston Watson, Jim Keltner, Brian Blade, and David Kempner; Duke Robillard, Bob Britt, and Bucky Baxter on guitar; Jim Dickinson on keyboards; Augie Meyers on organ and accordion; and Cindy Cashdollar on slide guitar. Fragments showcases both the spare sparseness of the Teatro sessions, where Dylan’s voice is the star, and the rich breadth and depth of all the instruments available in the Criteria sessions. I love and respect the Criteria recordings, which are, after all, the basis for the Time Out of Mind as I’ve known and loved it for decades. The Teatro tracks are completely mind-blowing, though, and it is such a gift to feel like you’re sitting in a room with just a handful of men, all listening to that slightly grainy, sometimes nasal in the old Woody Guthrie way, soaring and swooping, emotional and elegant voice leading the way.

Tonight when I chase the dragon

The water may change to cherry wine

And the silver will turn to gold

Time out of mind

—Steely Dan, ‘Time Out of Mind’ (1980)

********

Fragments’ first side contains Brauer’s masterful remixes of Time Out of Mind. For those who have complained in the past about Lanois’s original production, with too much mood and too many clouds distracting from Dylan’s voice — this despite the good popular reception of the record and the awards it won — rejoice. You want to hear Dylan’s voice stand out? Here you go. It’s both pleasant and an interesting exercise to listen to these tracks with entirely different emphases and possibilities. In this sense, these songs are previously unreleased, at least in this form.

The next two discs are all outtakes and alternate recordings. Disc Two begins with the only song not by Dylan, and one of three in a row, from the Teatro sessions, that will knock you down. ‘The Water Is Wide’ flows down from an old Scottish folk song through Ireland, and across that wide water to America. Pete Seeger sang it in the late 1950s, and Liam Clancy soon after. Paul Clayton, Carolyn Hester, Joan Baez, many artists in the Greenwich Village folk scene into which Dylan arrived in January 1961 performed this song. He learned both the songs and the styles in which to sing them from all these people, particularly, I increasingly realise, Liam Clancy, a matchless master of delivery and phrasing.

Dylan sang it with Joan Baez during the Rolling Thunder Revue in 1975, and last performed it live once in the summer of 1990. At the Teatro, rippling guitars from Lanois, Dylan, and Garnier back Dylan’s sad voice, with the brush of drums joining in on the broken oak tree stanza. It’s a song from time out of mind in the purest sense of the phrase.

‘Dreamin’ of You’ (later soldered in part into ‘Standing In the Doorway’, which sounds nothing like it) follows, with a zingy, sparkling start that you can almost see, like a spinning disco ball, despite Dylan’s leadoff statement that “The light in this place is really bad.” About 'Red River Shore’ — well, I’ll save that for the last.

‘Love Sick’, though Dylan has performed it 916 times to date, remains well known as the song he performed with his road band at the 1998 GRAMMYs, when performance artist Michael Portnoy, shirtless and with “SOY BOMB” painted on his chest, sprang on stage after the third verse and began gyrating to the music. Dylan didn’t miss a word, and Larry Campbell— whose contributions on many of this album’s live versions are diamonds and gold — strode flawlessly into his electric lead as Soy Bomb was removed by security.

‘Love Sick Version 1’ slow-walks you on the guitars into Dylan’s first lines about walking. The way the instruments, every one, follow Dylan like His Master’s Voice is something musicians on his records, and in his bands, haven’t done since Blonde On Blonde in the studio, and The Band live. Honestly, musicians haven’t done it again until the current band, now on a brief (Deo volente) hiatus from accompanying Dylan on his Rough And Rowdy Ways tour. ‘Love Sick Version 2' is thumpier, with the sound of an old-fashioned watch winding at the start. Dylan’s voice is much stronger, with the instruments tagging along in little interjections, like scurrying creatures in the alley down which the singer is walking.

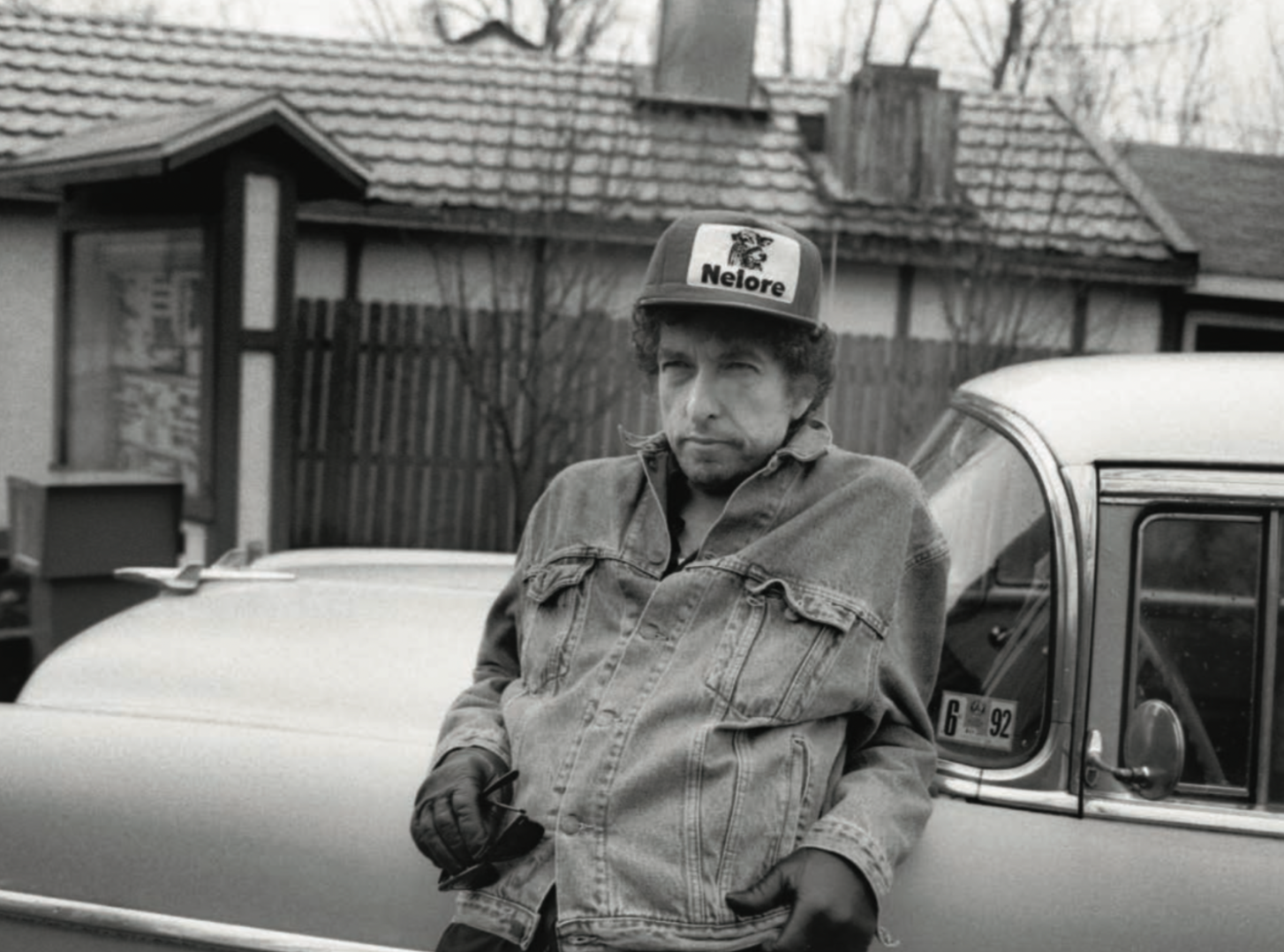

Bob Dylan. Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.

Bob Dylan. Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.How do you leave the magisterial ‘Mississippi’ off a record? Maybe Dylan felt protective of his listeners, and wanted to spare us the emotional blast of the lengthy double feature of ‘Mississippi’ and ‘Highlands’. Remember, too, that this is the man who left 'Blind Willie McTell’ off an album. Now, you only think you don’t need to listen to six versions of ‘Mississippi’. You absolutely do. I was lucky enough to hear it repeatedly when it was in Dylan’s set list from 2001 until 2012, and wouldn’t trade a single evening. I wish with all my heart this song would come back — all the way — to live performance.

'Mississippi Version 1' is a surprisingly sprightly thing that sounds a little like ‘The Mighty Quinn’. It’s a honky-tonkin’ toe-tapper, with skiffly drums and twangy little string riffs. The mule’s kickin’ in the stall, but almost no other lyrics are changed, though he shuffles over a few. His vocal is ablaze. This is easily one of my favourite tracks on Fragments. I’d have given a whole lot to hear Bob and Levon Helm sing this version in a trading-verses’duet, with Levon manning the drums. “Mississippi Version 2' is a slow, preachy rocker with a one-two beat. The pretty standardised lyrics on these versions don’t show the massive amount of work Dylan put into the song, as manifested in his handwritten archival drafts.

Those drafts are plentiful for ‘Highlands', too —even more so. He really spent a lot of time over that scene in the Boston restaurant and the Eliotic conversation with a waitress. Yet there are only three versions here, perhaps because of its length: the remix, a version from the Criteria Studios sessions showcasing the slides and steel glides of Bucky Baxter and Cindy Cashdollar, and a live recording from Newcastle, Australia, 2001.

‘Can’t Wait’ is generously set forth on Fragments. ‘Can’t Wait Version 1’ has a quiet, tickle of a stringed start, Dylan’s voice spare and barely accompanied at first. This punches out the sharper, more personal words. Then the other instruments start, and veer into edge and roughness, with the exhausted yet sinister drums keeping pace with the singer.

“I can’t wait, wait for you to change your mind

I can’t wait, wait for you to walk the line.

Ya ever feel just like your brain’s been bolted to the wall

All the screws were tightened and you’re cut off from it all

I don’t know, maybe for you it’s not that late

But as for me, I don’t know how much longer I can wait.

It’s got to end, everything about it just feels wrong

I’ll pretend being close to her is where I don’t belong

Well, my back is to the sun because the light is too intense

I can see what everybody in the world is up against

That’s how it is when things disintegrate

But I don’t know how much longer I can wait

Skies are gray, life is short and I think of her a lot

I can’t say whether I want the pain to even end or not

I’m trying to stand on my own two feet

And not have to lean on everybody that I meet

I’m breathin’ hard, I’m trying to concentrate

But I don’t know how much longer I can wait.

The trees are shakin’, I’ve rode in through the stormy weather

My heart is breakin’, but I’m holdin all the parts of it together

My hands are cold, the end of time has just begun

I’m gettin’ old, anything can happen now to anyone

Well I got one heel in front of me and the other one behind

I’m strollin’ through the lonely graveyard of my mind

I thought somehow I would be spared this fate

But I don’t know how much longer I can wait.”

An alternate lyric emphasises even more both the lonesomeness and the beloved’s bad actions:

“Loneliness around me, diggin’ in me like a rake

What a piece o’ work she is, to cause my heart to break

I thought somehow that I’d be spared this fate

And I don’t know how much longer I can wait.”

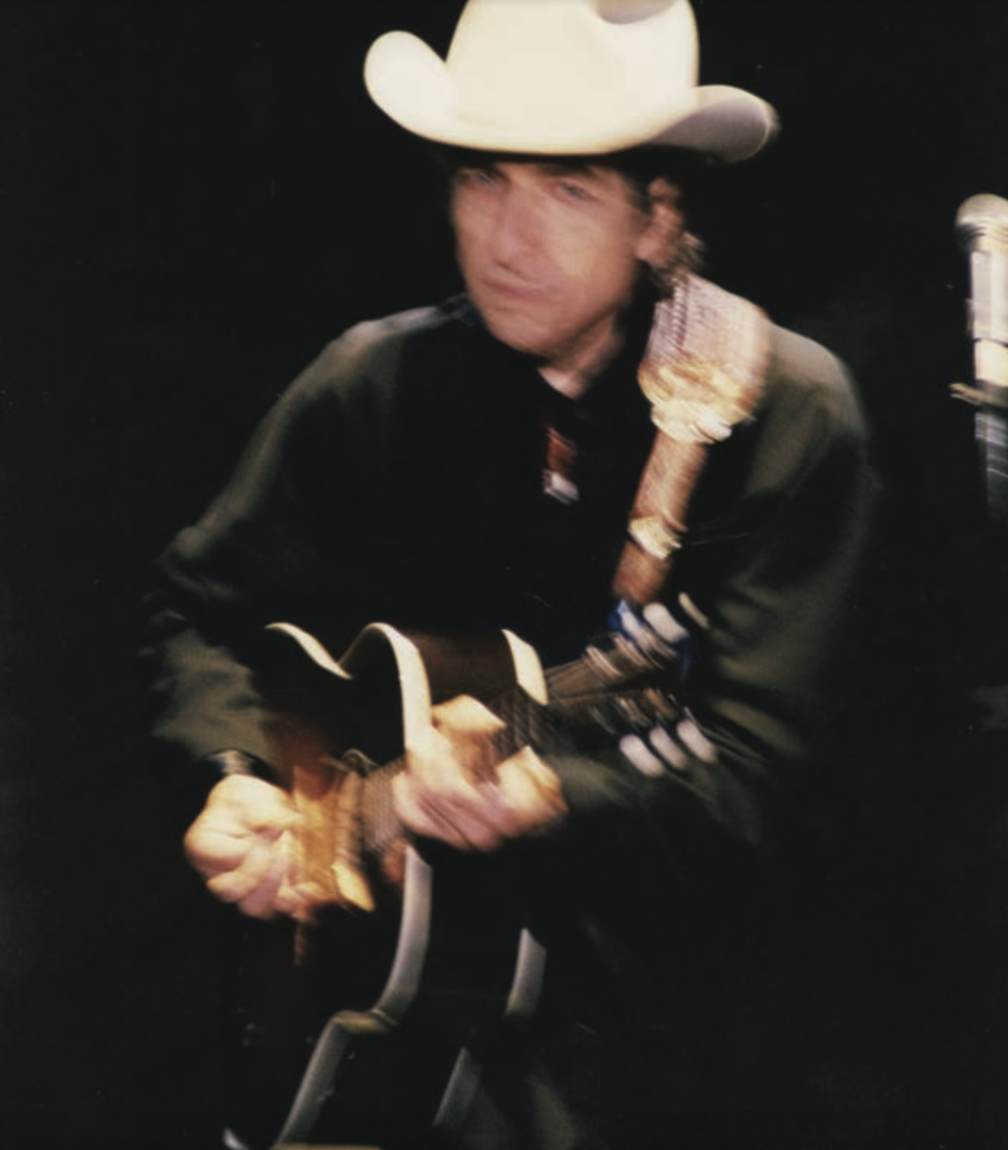

Bob Dylan. Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.

Bob Dylan. Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.'Can’t Wait Version 2’ is almost a slow funk dance, though truly not a song you’d ever want to dance to. A ghostly muffled yell shakes you just before the words begin to fall.

‘Marchin’ To The City’ is a quickstep march into who knows what, but it’s better than the circumstances of lost love in which the singer finds himself—lost love as the second notable theme of Time Out of Mind, after ageing and mortality.

The couplets make you reflect on all these things: “Loneliness got a mind of its own / More people around, more ya feel alone.”

“My house is burnin’ up to the sky / I thought it might rain but the clouds passed by / Sorrow and pity rule the earth and the skies / I’m not lookin’ for nothin’ in anyone’s eyes.”

“I just don’t know what I’m gonna do / I was all right til I fell in love with you.” He wants to get to that city fast, and get her out of his head, if that’s a thing that can ever happen—and I don’t think it can. Dylan retooled this song into ‘Till I Fell In Love With You’.

'Make You Feel My Love’ has become the most covered song on Time Out of Mind. Dylan last performed it live in 2019, and has sung it a modest three hundred or so times, but others have taken it and run with it. Billy Joel’s version was actually released the month before Dylan’s. Adele’s has sold millions of copies and is one of her most recognised covers, with fans insistent that she wrote the song. ‘Make You Feel My Love (Take 1)’ is delicate yet insistent, with the pedal steel or slide guitar propelling the track. Slight changes in the lyrics are mostly added words:

“When the rain is driftin’ in your face

And the whole wide world is on your case

I could offer you a warm embrace

To make ya feel my love.”

Some are more major:

“The storms are ragin’ on the rollin’ sea

And on the highway of regret

The winds of change are blowing wild and free

You ain’t seen nothin’ like me yet.”

‘Dirt Road Blues’ may have a snappy beat, but the words are bleak. Dylan loves a good blues, and has sung as well as written many from his earliest days on a stage. The wah-wah rise and fall from major to minor key and back might sound danceable, but no, this is an abandoned-love, blood in the eyes, trapped and I have to get out of here song. It is akin to 'Cold Irons Bound’ and ‘Love Sick' and the burn-it-all-down of ‘Standing In the Doorway’, though a truer old-style blues than any of them.

The previously unreleased versions of all these lost-love songs are stunning. Dylan gives good lost love. ‘Cold Irons Bound’ is one of his best songs of the end of the last century, always electrifying in concert. The track on Fragments from the Criteria sessions is ominous and stirring, the verses shifted in order and some of the lyrical changes shock: “Reality for me got too many heads” and "Well, there’s so many stones in a pathway hurled / It’s so easy to be corrupted in my corner of the world.”

‘Standing In the Doorway Version 1’ is a swingy bop that, like ‘Dirt Road Blues’ and some of the other sonically upbeat songs, carries hard words new to your ears: “Too many silver spoons / Too much salt in my wounds.” “I know this horse I’m ridin’ could throw me but he don’t.” “Don’t pass me by / Give me liberty or let me die.”

Bob Dylan. Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.

Bob Dylan. Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.To go on would be a disservice, really. Listening to songs I thought I’d known all my grown-up life with ears made new is such a treat. Find the surprises yourself, compare and contrast, revel in them. Take your time with Fragments. These fragments Dylan might have shored against his ruins in 1997 now sound much less like the intimations of mortality that critics took them for back then.

They’re far more intimations of immortality, in Wordsworth’s conception of the phrase. When the great Romantic poet celebrated, in that most famous ode of his —“Intimations of Immortality From Recollections of Early Childhood” — the way in which “The Clouds that gather round the setting sun / Do take a sober colouring from an eye / That hath kept watch o'er man's mortality[,]” Wordsworth had his finger on the same pulse beating in Bob Dylan’s art nearly two centuries later.

The songs of Time Out of Mind, and from its sessions, have on Fragments a freshness and creative spirit we’re able to hear, thanks to the numerous versions and variants, listening like flies on the wall as the songs are being made. That’s the joy of these “official bootleg” albums, after all.

********

O, then, I see Queen Mab hath been with you.

She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comes

In shape no bigger than an agate-stone

On the fore-finger of an alderman,

Drawn with a team of little atomies

Athwart men’s noses as they lie asleep;

Her wagon-spokes made of long spiders’ legs,

The cover of the wings of grasshoppers,

The traces of the smallest spider’s web,

The collars of the moonshine’s watery beams,

Her whip of cricket’s bone, the lash of film,

Her wagoner a small grey-coated gnat,

Not so big as a round little worm

Prick’d from the lazy finger of a maid;

Her chariot is an empty hazel-nut

Made by the joiner squirrel or old grub,

Time out o’ mind the fairies’ coachmakers.

—William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, I.iv.54-67 (1597)

********

‘Red River Shore Version 1’, from the Teatro sessions, is the only song I stopped and listened to many times in a row before going on. It is with this throwback song, perhaps Dylan’s best tribute to the old Western cowboy plaints, that this essay on a first listening to Fragments concludes. Here’s why. Dylan’s Mexicali-blues-ridden voice, with his Guthrie intonation and his clear joy in spinning out the story that sounds like it came from well before Modern times, and in the words themselves and the tune, is such a pleasure to hear.

This is a man who loves what he does, clearly takes pleasure in the company in which he plays music in a studio or on stage, and so values those who have kept the old songs alive for centuries — just as his will be kept alive in time not yet come to mind.

Anne Margaret Daniel.

Bob Dylan. Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.

Bob Dylan. Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.Credits

Fragments—Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997): The Bootleg Series Vol. 17

Bob Dylan

Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment

Produced by Jeff Rosen and Steve Berkowitz

Time Out of Mind (1997)

Produced by Daniel Lanois

Personnel

Teatro sessions, 1996:

Bob Dylan: vocals, guitar, and piano

Daniel Lanois: guitar and organ

Tony Garnier: bass

Tony Mangurian: drums and percussion

Criteria Studios, 1997:

Bob Dylan: vocals, guitar, piano and harmonica

Daniel Lanois: guitar

Duke Robillard: guitar

Robert Britt: guitar

Bucky Baxter: guitar and pedal steel

Cindy Cashdollar: slide guitar

Augie Meyers: organ and accordion

Jim Dickinson: keyboards

Tony Garnier: bass

Winston Watson: drums

Jim Keltner: drums

David Kemper: drums

Brian Blade: drums

Tony Mangurian: percussion

Live recordings 1998-1999:

Bob Dylan: vocals and guitar

Larry Campbell: guitar

Bucky Baxter: pedal steel and slide guitar

Tony Garnier: bass

David Kemper: drums

Live recordings 2000-2001:

Bob Dylan: vocals and guitar

Charlie Sexton: guitar

Larry Campbell: guitar, mandolin, pedal steel, and slide guitar

Tony Garnier: bass

David Kemper: drums

Bob Dylan. Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.

Bob Dylan. Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment.All lyrics © 1997 Special Rider Music; previously unpublished lyrics © 2023 Babinda Music. All artwork from the album under review courtesy of and © Columbia Records / Sony Music Entertainment 2023.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 26 Jan 26

Anti-ICE protest to take place in Dublin this afternoon

- Opinion

- 26 Jan 26

Mary Robinson criticises Trump's Board of peace: "a delusion of power"

- Opinion

- 26 Jan 26

Education Special: Expand your horizons through these creative courses

- Opinion

- 26 Jan 26