- Opinion

- 30 Nov 23

Former Dunnes Stores strikers seek funds to bring a play based on their story to Ireland: "There’s a lot of people who genuinely don’t know it happened"

In July 2024, it will be 40 years since the beginning of the famed Dunnes Stores strike – in which a group of young shop workers in Dublin, at enormous personal sacrifice, took a stand against apartheid in South Africa. The former strikers want to mark the anniversary by bringing an acclaimed play about their experiences to Ireland. To do so, however, they need funds – and, as Vonnie Munroe and Cathryn O’Reilly tell us, they’re looking to the unions to help.

There’s a plaque on Henry Street in Dublin that thousands of people pass every day, though it can be easy to miss. It bears the names of 11 former shop workers and a trade union organiser, alongside a quote by Karl Marx: “Labour in a white skin can never free itself as long as labour in a black skin is branded.”

That plaque serves as a small but crucial reminder of a story that, almost 40 years on, demands further retelling and recognition. It’s the story of 11 young people taking on both a major retail company and the racist system underpinning an entire country on the other side of the world – and, despite the immense challenges faced, making a real difference.

“I think there’s a lot of people who genuinely don’t know it happened,” Vonnie Munroe, one of the names on that plaque, reflects now. “40 years ago, there were people fighting for the rights of Black South Africans to live a proper life. Those people don’t know that this was done in the Irish name, for Black South Africans.”

Vonnie Munroe & Cathryn O'Reilly. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

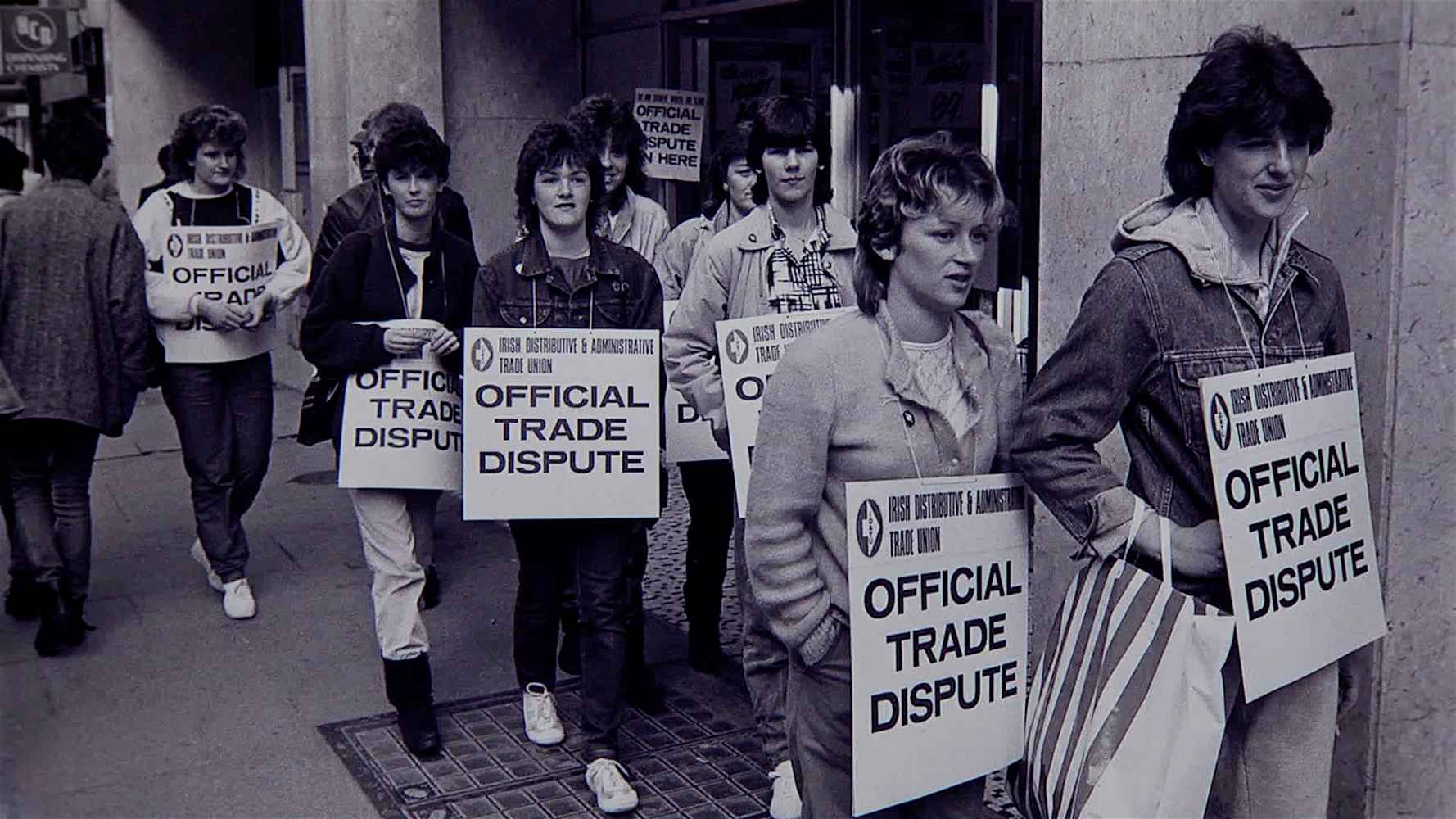

Vonnie – and Cathryn O’Reilly, who joins her in the Hot Press office today – took to the street back in 1984, as part of the Dunnes Stores workers’ strike against apartheid in South Africa, which went on for three years. Their experience is now the subject of a play, Strike!, which ran in London earlier this year.

“A woman came up with two Outspan grapefruits in her basket, and kind of hovered between Alma [Russell] and Mary [Manning],” Cathryn says of the background to the strike. “In the end she went to Mary, and Mary explained to her that, because of our union policy not to handle South African stuff, she couldn’t take for them.

“The manageress who was standing behind her told her to close her till, and Mary was called up to the office,” she continues. “They asked her if she wanted to change her mind. Then they told her that she was suspended indefinitely. So Mary clocked out, and the rest of us clocked out with her.”

A group of workers, mostly made up of young women, walked out in solidarity with their colleague, and began their strike outside the Dunnes Stores on Henry Street in Dublin in July 1984, alongside Brendan Archbold of the Irish Distributive and Administrative Trade Union (IDATU, which has since become part of Mandate).

“Everyone was thinking, ‘This will be for two weeks,’” Vonnie recalls. “And the weather was fantastic! That will tell you the level we were at. We’d no problem going on strike for one of our colleagues – that’s what we were looking at it as. But then we educated ourselves, and we realised that, ‘We’re not only out for Mary. This is a whole new issue to us.’”

While both clearly had a strong sense of empathy to begin with, they feel that their passionate stance against injustice largely evolved as the strike went on – describing their time on the picket line as “an education.”

Blood Fruit (dir. Sinead O'Brien). Irish Film Institute

From the outset, however, they were met with fierce resistance and hostility. At certain points, they had to picket at night as well as during the day, as delivery times were changed to avoid the strikers. They describe shutters at the back of the shop being closed down on them, and getting “bashed” with their own placards by those trying to push past and bring in products.

“When it got to the first Christmas, it was raining and it was cold, and everyone was tired,” Cathryn says. “People were just walking by us, doing their shopping. It was really hard.

“We also had the other people who were working away in the shop telling us that we should go back to work, and that we were dopes – and throwing stuff out the window on top of us!” she continues. “They’d be coming out at Christmas like, ‘Ah, what will I spend my Christmas bonus on?!’ While we were like, ‘What will we spend our £25 on…?’”

Learning to survive on that strike pay was like adapting to “a new lifestyle”, they recall. Both Vonnie and Cathryn were single parents, and Vonnie ended up losing her home during the strike.

“We did get a good lot of support, but it was very slow to start with,” Cathryn resumes. “People also didn’t really take us seriously, because we were girls, and we were all young. It was like, ‘Sure what would they know, they’re only kids!’”

When the support did come, however, it proved crucial in keeping spirits high. They give a special mention to the daily efforts of the late Nimrod Sejake, a South African political refugee in Ireland at the time. Nimrod, who had once shared a prison cell with Nelson Mandela, walked from the south-side of the city each morning to join them on the picket line. At the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement’s AGM, which the strikers were invited to, they also met Marius Schoon, a white South African anti-apartheid activist, whose wife and young daughter were killed by a parcel bomb. When he stood up and thanked the strikers, Cathryn remembers it having “a very profound effect on everybody.”

“From the stories that we heard, we realised that we were living a life of luxury, compared to these people,” Vonnie states. “Once we heard what we heard, we couldn’t unhear it. We had to keep going, no matter what. And when we got to the year mark, we said, ‘There’s no way we’re going backwards.’”

There were days when the crowds gathering to show solidarity for the strike would almost shut down Henry Street – with support also coming from miners in the UK, who were in the middle of their own major strike. In 1985, the Dunnes Stores strikers were even invited by Bono to sing backing vocals in Windmill Lane Studios for the Artists United Against Apartheid’s Sun City.

“My hair was soaking wet when I went down to the Windmill Studios,” Cathryn laughs. “I was in the shower, and my mother was like, ‘You’re wanted on the phone!’ We were like, ‘Are you having a laugh? Sing on a record with Bono?’ He probably had to go over our voices, because I can’t sing!’

“But I remember he was telling us, ‘Get angry, don’t be bitter. Get angry, don’t be bitter…’” she adds.

Another famous fan was Desmond Tutu, who, along with the South African Council of Churches, invited the strikers to visit South Africa. They raised the funds in one weekend, through bucket collections around Dublin pubs.

Their attempt to enter the country, however, sparked major issues. When trying to board their connecting flight in Heathrow, they were informed that – although Irish citizens going to South Africa didn’t require a visa – Leo Evans from the South African embassy in London had revoked that right in their case. After serious delays, furious fellow passengers, and fears from the airline about the flight being impounded, they ultimately made it all the way to South Africa – only to immediately be put on another flight back. Vonnie remembers the union organiser Brendan Archbold’s tongue-in-cheek description of the strikers on their return: “The 11 most dangerous shop workers in Ireland.”

The strike ended in April 1987, when the Irish government finally banned the importing of South African products. But as we approach the strike’s 40th anniversary, Vonnie and Cathryn are asking the unions for one thing only – to help them bring Tracy Ryan’s acclaimed play about the strike to Ireland, following its run at Southwark Playhouse in London earlier this year.

Strike! – Credit: Ardent Theatre Company

As an educational tool, they argue, the production could play a part in inspiring today’s young Irish people, of various backgrounds and ethnicities, to “take up the mantle, and do something within their own community.” The story of young working class people coming together to take a stand against white supremacy on another continent is particularly important to hear now – at a time when racist and xenophobic rhetoric has fuelled serious unrest in Dublin. Both Vonnie and Cathryn feel young people need to seriously engage with what’s going on in the world – even if it makes for tragic viewing – and not just rely on social media or hearsay for news.

“Before the strike, I would’ve said, ‘I’m only one voice. No one will listen to me!’” Cathryn reflects. “But after the strike, I could say to myself, ‘Well, there were only 11 of us – and I know it was a hard slog, but we got the Government to implement a ban on agricultural goods from South Africa.’”

They claim commitments were previously made by trade unions to help fund an Irish tour of the play – but such talk has since gone silent.

“We did an awful lot for ourselves, together, right through this whole thing,” Vonnie remarks. “So we should be able to push the unions, to let them do something for us now.”

“It will be 40 years next July – who’s to say we’ll be here in another ten years?” Cathryn nods. “We’re not getting any younger. They were able to get money to put it on in England, and it’s nothing even to do with England.”

“So just support us,” Vonnie resumes, in a direct plea to the unions. “We’re not going to be looking for anything off them ever again! If this got off the ground, we’d just be so happy.”

Vonnie Munroe & Cathryn O'Reilly. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 31 Dec 25

Climate crisis: "The battle must go on. The alternative is unthinkable"

- Opinion

- 24 Dec 25