- Opinion

- 05 Dec 22

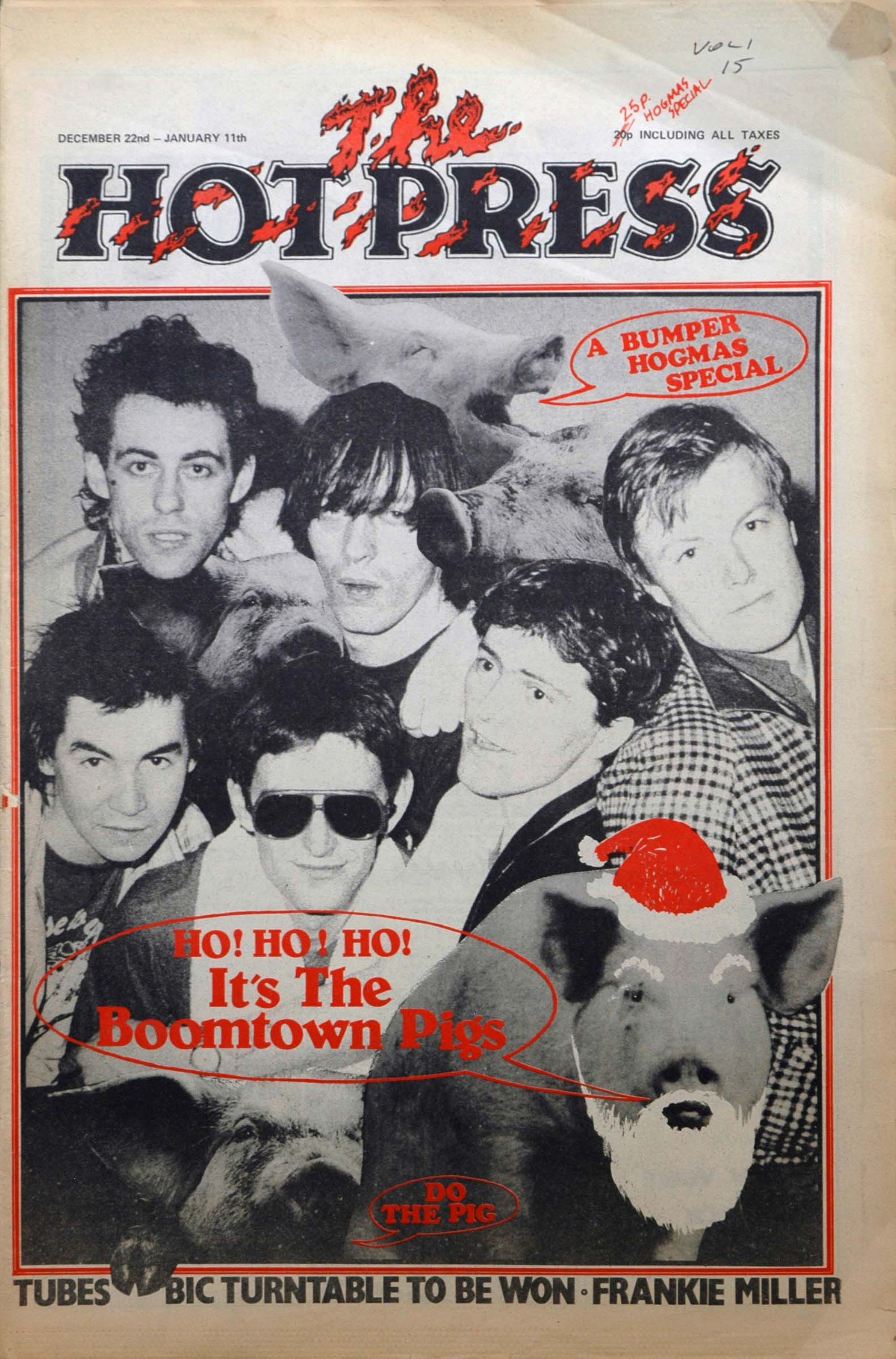

Garry Roberts, The Boomtown Rats and Ireland: "He knew that it was time for change"

When Garry Roberts and his fellow members of The Boomtown Rats – including Bob Geldof – were growing up, Ireland was dominated by the deeply insidious influence of the Roman Catholic Church. It is to the band’s enormous credit that they were the first successful rock band to openly express their opposition to everything the Irish representatives of the Vatican stood for – and a whole lot more besides. In addition, with Garry on guitar, they made a great noise...

Garry Roberts of The Boomtown Rats has died. When we first wrote the headline, the thought occurred that the second ‘r’ would confirm for fans the dread news that this really was the man they hoped it wasn’t. Garry Roberts. As in Garrick.

Rats fans will have winced. Garry. Christ, it couldn’t be. But it was. Just like that. Gone. This was the man who officially started the band. Who brought the rest of the crew together. Who threatened to quit immediately if they insisted on sticking with the outfit’s initial moniker The Nightlife Thugs.

The things on which fate hinges. They ditched a terrible name and came up with a good one.

Garry had the drive, ambition and determination necessary to get a rock ’n’ roll band off the ground. He wanted to make a dirty noise and knew that he needed the assistance of a posse, a gang, a bloody group – like The Rolling Stones, The Who, Little Feat or even Dr. Feelgood – to do it.

He got his mates Simon Crowe and Johnny “Fingers” Moylett involved. Arranged the meeting. Brought the boys together. And the beginning of a plan took shape...

Garry onstage with Bob, Rainbow Theatre, London, 1978

THE OTHER NATIONAL QUESTION

There are times when you embark on an adventure, or a trip, and after a few days or weeks you know that the guys in the minibus are not ones that you really want to dally with. They don’t have the necessary bottle. They don’t have the musical chops. They aren’t especially interesting or even very nice. Whatever.

Garry ended up on a minibus with Bob Geldof, who just happened to be one of the most driven and ambitious characters ever to put a pair of underpants on. Sure he wanted to be in a band. But he wanted it to be a great band. That would press immediately ahead with a plan for world domination no less. That was the cliche of the time, but more than anyone else, Geldof meant it. He wanted to show all the assholes. He wanted to elbow all of the other pretenders aside. He wanted to think big. He wanted hits, and he wanted them now.

That was all okay with Garry. In fact it brought a smile to his face. He wanted all of those things too. Maybe not with the ingrained single-mindedness of Bob, but with a deep-seated passion nonetheless. He wanted to be a great player. To do great gigs. To be part of a band that wrote great songs. To be a guitarist that people could look up to. To make that instrument sing.

Like the rest of the Rats, he wanted it all. But more than anything else, he wanted to be a musician who was good enough to be taken seriously. He wanted to make a mark in the right way. And he did.

He was a looker too. In the early pics of The Boomtown Rats, he could stand four-square alongside Bob Geldof. He was handsome. He had a sense of style. He had good features. And a quiff. He had the makings of a rock star. And – like Pete Briquette on bass – he could play, which really did matter. So, when the band signed to Ensign Records, in a deal that delivered money into the bank on a scale that none of them had ever dreamt of, well, Gerry saw that as a good start. He was in it for the long haul.

Ireland had produced some extraordinary musicians during the 1960s and the 1970s. There was Them. Van Morrison. Rory Gallagher. Skid Row. Thin Lizzy. Gilbert O’Sullivan (he had emigrated from his Waterford home at the age of seven). And slightly lower down the pecking order, Dr. Strangely Strange, Jon Ledingham aka Jonathan Kelly, Granny’s Intentions, Mellow Candle, Tír na nÓg, and of course Horslips. But none of these artists had been overtly political. None of them was clear where they stood on the other vital national question: was the existing, deeply incestuous relationship between Church and State in Ireland even remotely acceptable?

And if not, what could be done to put gelignite under it? Me and a few of my mates had an idea...

THE TIDE OF HISTORY

Hot Press launched in 1977. The Boomtown Rats started releasing records that same summer. We shared an incendiary conviction that the stranglehold operated by the Roman Catholic Church would have to be shattered. From the outset, the Rats had no compunction about going head to head with the authorities. They were happy to get up people’s noses. As the founder of the group, if Garry Roberts had been averse to any of this, he was in a stronger position than anyone else to shout stop. But he didn’t. He understood. He knew that it was time for change.

Bob Geldof was the lyricist. He was a born agitator. But Garry shared Geldof’s vision of a better Ireland, free of the chains of oppression winched tight by the greasy-palmed handshakers and sibilant plot whisperers of the Church – and indeed by the agencies of the State that were so dismissive of, and condescending to, the needs, desires and views of young people. Especially the desires.

In ‘Looking After Number One’, the Rats captured a very Irish form of punky insolence. The song’s catch-cry – “I don’t wanna be like you” – was addressed to the guys who ran the shit-show of mid-1970s Ireland. ‘Rat Trap’ was what happened when you got stuck on the local treadmill, your freedom sacrificed at the altar of brutal economic necessity and the kind of compromise that had us going nowhere.

The Boomtown Rats broke the mould by giving the two fingers openly to the establishment.

The infectiousness of their jaundice was given extra force by the immediacy of their initial success. They had hits straight away. They showed other Irish musicians not only that Top of the Pops was an attainable way-station, but that appearing on it was only the start. That you could produce a No.1 hit just like that – if, that is, you had the energy, strength, conviction and talent. ‘Rat Trap’ was the first ever UK No.1 by an Irish rock band. Garry Robert’s guitar wielding menace was integral to the sonic thrusts that gave it an edgy glory.

The Rats arrived back in Dublin to appear on the Late Late Show and they were in ebullient form, dripping contempt for the shysters and the gombeen-men, and while they were at it, for Rome rule. Watching them have a go was fun. The more outraged the tinpot diehards became the better. The coded hand-shakers – the Knights of Columbanus and members of Opus Dei – joined forces to deny them the opportunity to play a homecoming show, planned for Leopardstown Racecourse, in what was dubbed the Pope’s tent. The suggestion of sacrilege had them whispering to one another in the local council, in the Dáil and in the judiciary. That was how Ireland was run.

In Hot Press, we played the same song only differently. We knew that a generation was tuning in. We felt that the tide of history was beginning to shift in favour of a country that would be free of the oppressive, sterile grip of Rome. It would be a long road. We just didn’t know how long. We kept making the arguments anyway for everything the Church opposed: for gay rights, for access to contraception, for secular education, for abortion rights, for an end to the patriarchy, for the removal of Church influence, for an end to censorship, for equality for all in what was supposed to be a Republic.

The Boomtown Rats on The Late Late Show

ARRIVAL OF THE PANDEMIC

In 1980, The Boomtown Rats released ‘Banana Republic’. It was Geldof’s and the Rats’ view of Ireland in its most distilled form. In it, Bob and the band railed against the collusion between Church and State.

“Banana Republic,” Geldof sang, “Septic Isle/ Screaming in the Suffering sea/ It sounds like crying/ Everywhere I go/ Everywhere I see/ The black and blue uniforms/ Police and priests.”

He also yoked violent nationalism into what was a peculiarly local cesspit of nastiness.

“Forty shades of green, yeah/ Sixty shades of red/ Heroes going cheap these days/ Price, a bullet in the head.”

But the baleful conspiracy of the Bishops and the Taca men that propped up the venal Fianna Fáil governments of the time was a particular target, as Geldof dismissed the insidiousness of their hypocrisy in the line, “The purple and the pinstripe/ Mutely shake their heads.”

The track made it to No.3 in the UK, Germany, Norway and Ireland, making it their second biggest hit globally after ‘I Don’t Like Mondays’. They wrote great songs and made great records afterwards – ‘Dave’ from 1984’s In The Long Grass was a stand-out – but music had been pulled in a different direction by the New Romantics and the fizz went out of the project commercially. In Band Aid and Live Aid, Bob Geldof found a different platform from which to rail against stupidity and injustice. And he did.

The Rats faded and split in 1996. Garry Roberts worked as a sound engineer with Simply Red and Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, among others, weaning himself off his addiction to playing the guitar. But of course the impulse never really went away. He subsequently kicked around playing the blues with fellow Rats-man and childhood friend Simon Crowe in The Velcro Files, and did other things to earn a crust. He wheeled out a version of the Rats, playing the hits with Crowe on drums. And so it came as a kind of blessed relief when Geldof got back on board, re-forming The Boomtown Rats officially in 2013.

The band made the album Citizens of Boomtown and released the film Citizens of Boomtown: The Story of The Boomtown Rats in 2020, both of which were positively received by critics – but scuppered commercially by the arrival of the pandemic within a week of the Dublin premiere of the movie. It was a desperately cruel blow. They had been dreaming big again, only to be undone by forces entirely outside their control. And so the journey twisted on.

I hadn’t spoken to Garry for some time, but I met him when he was in town with The Boomtown Rats, for the Late Late Show special celebrating Bob Geldof’s 70th birthday. I’m really glad that we got to speak. He was in properly good form that night and loving being back in the game with Bob and the boys.There was, I am sure, more to come from the Rats. But perhaps not, now that Garry is gone. His loss is, in a sense, the end of an era. Will it bring the Rats story fully to a close? That’s up to Bob Geldof, Pete Briquette and Simon Crowe. But the symbolism is unmistakable, making it an especially sad moment for Irish music – and for everyone who loved The Boomtown Rats, and who understood and appreciated what they achieved for this country culturally, musically – and politically.

AN OMERTA PREVAILED

I thought about their legacy recently when news emerged of the sexual abuse visited disgracefully on dozens of boys in Blackrock College, where Bob Geldof went to school. People are asking the question: how come it took so long for this to come out? Clearly, with so many priests involved, abuse was rampant. Hundreds were being systematically and brutally molested by these paragons of Catholic religious values. Thousands of people must have known.

So why – as stories of the horrific abuse of people by the Christian Brothers, the De La Salle Brothers, by nuns running so called Mother and Baby homes, by the thugs in reform schools, by individual priests and others in the South Dublin rugby-playing schools of St. Mary’s College and Terenure College, and so on and on – did no one come out screaming about the Holy Ghosts (now the Spiritans) in Blackrock College and in Willow Park?

It is a good question. But it goes back to something fundamental. There was a conspiracy of silence. As a kid you were made to believe that you were in the wrong. And that inversion of the truth was brutally enforced by the religious orders and their acolytes until corporal punishment was banned in 1982. But the omertà remained in place. The Roman Catholic Church had wormed its way into a position of such influence and authority that even otherwise decent people were silenced and became complicit.

I claim no great insight when I say that I knew, even as a teenager, that it was a stinking edifice that needed to be challenged. That had to be confronted. That needed to be driven from the grotesque position of power it held.

Back in 1977, I and others on the good ship Hot Press understood that it was as important for us – or likely more important – to do everything in our power to break the stranglehold that the Church exerted over the affairs of the State here in Ireland and to challenge their assumed authority every step of the way. Gradually, a generation came through – in media in particular – who were of a similar mind. Women were more to the fore in journalism than ever before. The feminist agenda was starting to work.

And so what happened to Joanne Hayes in Kerry, in 1984, in the infamous Kerry Babies case, could not be hidden. What happened to 15 year-old Ann Lovett – pregnant when she died beside a grotto in Granard, Co. Longford, also in 1984 – could not be disguised, as the Church henchmen would have wanted it to be. The dark secrets started to pour out. And the whole edifice of Irish authority was revealed to be a stinking morass of hypocrisy, dishonesty and deceit.

And yet, there remain instances where the wheel still turned very slowly. In relation to Blackrock College, an omertà prevailed until two brothers David Ryan and Mark Ryan spoke to one another and realised that they had both been abused by Spiritan priests – and ultimately decided to go public together in a brilliant RTÉ Documentary on One programme.

For us here in Hot Press, it is just another confirmation that our convictions were more than justified. It is a dark vindication, as it must be for Bob Geldof – and as it would have been for Garry Roberts. And so in his honour today, we can say this much. It is beyond time to finally end all forms of religious control in our educational system. There is nothing good in this religion they preach. The actions of the clerical abusers, and the way in which the congregations – all of them – and the hierarchy covered up the abuse says everything we need to know about what they represent.

Power. Money. Corruption. The interests of the Holy Roman Empire and it remnants in the Vatican – a city that, by the way, was signed into existence by the Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini. Garry Roberts may not be around to see it, but it is time to move on. To finally consign the septic isle to the dustbin of history.

The new issue of Hot Press is available in shops now – or order online below:

RELATED

- Opinion

- 17 Dec 25

The Year in Culture: That's Entertainment (And Politics)

- Opinion

- 16 Dec 25

The Irish language's rising profile: More than the cúpla focal?

- Opinion

- 13 Dec 25