- Opinion

- 23 Nov 21

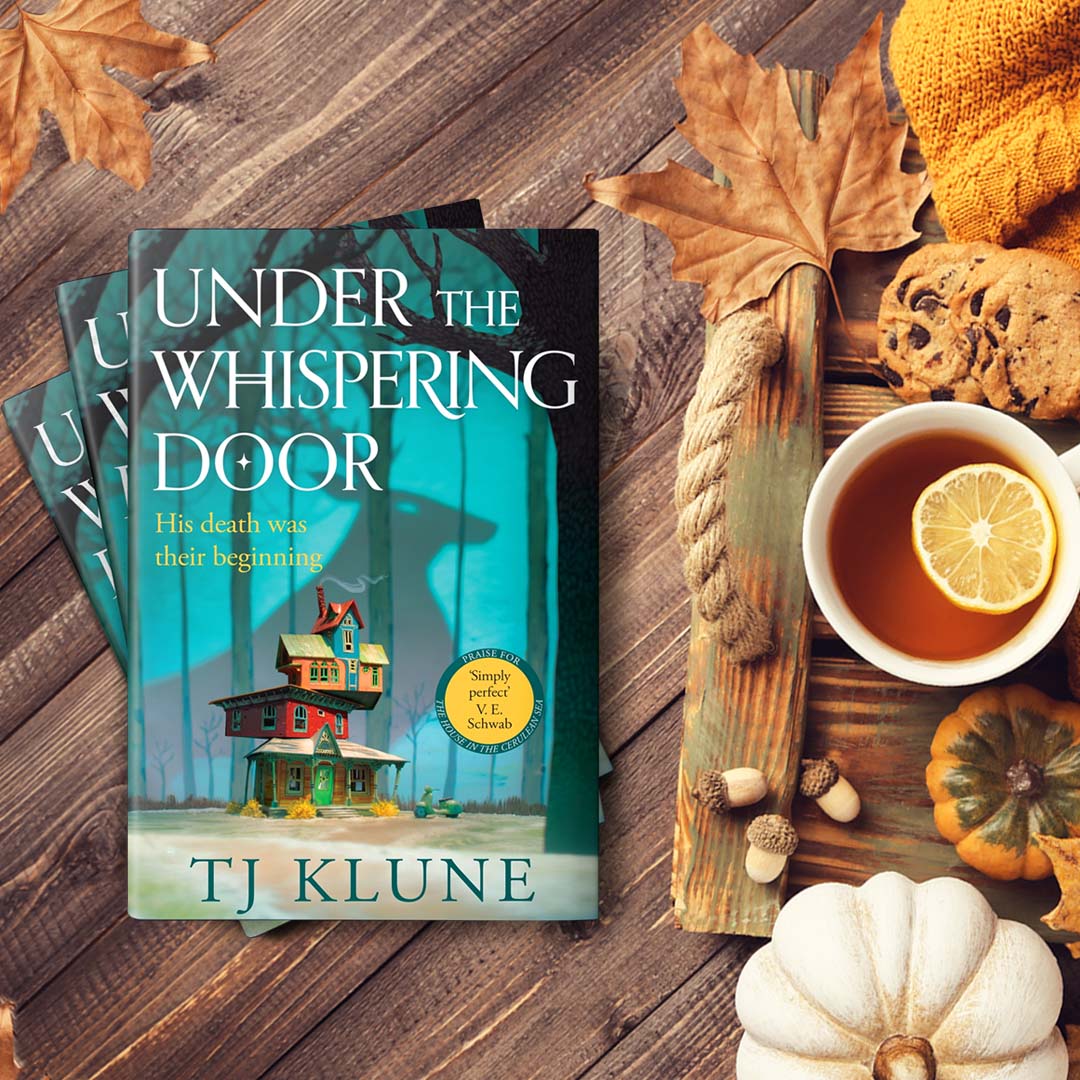

US romantic fiction author TJ Klune – known for his sensitive portrayal of LGBTQ+ characters – discusses his latest novel Under The Whispering Door, a powerful and moving exploration of grief.

This interview is the only thing holding TJ Klune back from his vacation, he doesn’t mind. The Oregon native is refreshingly eager to discuss his new novel, Under The Whispering Door. Everything about this work of fantasy fiction takes the reader by surprise, somehow mingling grief with feel-good humour. It’s filled with Klune’s signature warmth and empathy.

Now based in North Virginia, TJ Klune first rose to prominence in 2011 with his debut, Bear, Otter And The Kid. He earned a reputation for penning tales of queer romance, with a tender eye for detail, There were accolades aplenty for Into The River I Drown (2013) and New York Times bestseller House In The Cerulean Sea (2020). The latter was inspired by the so called Sixties Scoop, which saw the Canadian government remove Indigenous children from their homes and place them with white, middle-class families.

Under The Whispering Door goes down another route entirely. When a reaper comes to collect cold-as-ice lawyer Wallace Price from his own funeral, Wallace suspects he might be dead. Instead of leading him directly to the afterlife, the reaper takes him to a tea shop in a small village. There he meets Hugo, the ferryman for souls who need to cross over. With Hugo’s help, Wallace finally learns about all the things he missed in life – including love. Heartwarming and heartbreaking, this absorbing tale of grief and hope is told with Klune’s characteristic gentle touch.

I speak to the author over Zoom, with his dog Hendrix (who appears in the novel as Apollo) observing in the background. TJ recalls the last time he visited Ireland.

“I was there back in 2016,” he recalls. “Myself and a few friends of mine flew into Shannon and did a three week-long trip around the country, before travelling around the UK. They lost my luggage so I was wearing the same clothes for like two days. It was a good trip. We saw wonderful things. It was on my bucket-list for a while.”

Advertisement

The 39-year-old faced a devastating loss in December 2016, when his partner, fellow author Eric Arvin, tragically passed away. That experience has informed much of his new work.

“Every author puts parts of themselves into their books,” says Klune, “but I tend to avoid trying to emulate my characters with real life counterparts, because it could be ethically blurry. I’ve put more of myself into this project than any other. It was a deeply personal story for me to write, given that I had lost my partner a few years ago. The story of Cameron really resonates with me.”

Cameron’s character is a chilling figure when we first come across him, a soulless creature who seems to have lost his way. Meanwhile, beings known as husks roam the area surrounding the tea house.

“That’s how I felt after losing my partner,” Klune acknowledges. “Emptied out. I felt hollow. There are many forms of death; unexpected, violent, quiet. I think the greatest taboo associated with grief and death is suicide. The religious line of thinking says that people who die by suicide aren’t going to know eternal life because of their ‘sin’. That has always absolutely bugged the shit out of me. These people made a choice they felt was the only option they had, and you want to believe that they will continue to suffer? There’s no logic behind that.

“I wanted Cameron’s character to show that people who make such desperate decisions aren’t bad people. They’re lost, and they need someone to help guide them home. I could easily have been Cameron, but thankfully I had my friends, my family and a very, very good therapist who helped me work through all of that. While it is a devastating loss, the person who took that action shouldn’t be blamed. Suicide isn’t selfish. It’s a means to an end for people who cannot see any other way out.”

Interestingly, Under The Whispering Door began life in a completely different form.

Advertisement

“Years ago, I had this idea for a book about the bureaucracy of the afterlife,” reflects Klune. “There’s a scene in that ‘80s movie Beetlejuice where Gina Davis and Alec Baldwin die, and they’re basically going to this cubicle hell, with a social worker asking them to fill out paperwork. The idea of death being as bureaucratic as life fascinates me. Then somebody created The Good Place and did a much better job than I ever could have ever done. It wasn’t until I read Dickens’ A Christmas Carol for the first time that I got an idea how to do it from another angle.

“At the very end of the book, it’s like a switch flips and all of a sudden Scrooge becomes a good person, and everything is wonderful. It always bugged me a little that you never saw him do the work to actually become a better person. I wanted to take it one step further. Instead of a living man being shown the error of his ways, what would happen if that same type of man died and couldn’t do anything to change his past life?”

The character of Hugo is brimming with compassion, empathy and a wicked sense of humour. The antithesis of Wallace at the beginning, his role is to help the dead reach the afterlife.

“I started researching palliative care and I came across something known as death doulas,” TJ explains. “Their job is to help the families with the first stages of grief and help the dying with acceptance. That informed the character of Hugo, because he’s like a death doula, therapist and friend combined into one character.”

Hugo’s adoration for growing the tea leaves that fill his cafe mirrors the intense care he harbours for everyone around him, even a man as seemingly unloveable as Wallace.

“I find it fascinating that tea plays a part in every single culture around the world,” says Klune. “There’s a Chinese legend about an emperor sitting under a tree, and a leaf falls into his cup of hot water. That supposedly is how the idea of tea started, and it was initially used as medicinal. It wasn’t necessarily for pleasure. No matter what background or culture you come from, death has always been a part of life.

“If you live long enough to learn what love is, you eventually know what grief is. That just seems ancient as well. Combining these two things seemed like a natural fit, so that’s why I set the book in a tea shop.”

Advertisement

While Klune is a white author and Wallace Price is a white protagonist, the remaining primary characters are all people of colour. Wallace’s Reaper Mei is Chinese-American, while Hugo and his grandfather Nelson are Black. Klune is acclaimed for his intensely loving ability to write LGBTQ+ and neurodivergent characters from a unique perspective.

“Representation needs to be organic,” he says. “I also need to take care with the fact that I write characters of colour, which is why I spoke with people from these communities. I read blogs and posts by authors of colour and I also have what are dubbed ‘sensitive readers’, who make sure that I’m doing right by my characters.

“Much like the idea of sexuality, these things can’t be just ticking boxes. A lot of authors basically slap paint on a character and say, ‘Diversity, hooray!’ That does more harm than good. It needs to feel that these are real people. They need to feel lived in.

“This book also isn’t defined by the sexual orientation of its characters. They just happen to be queer or bisexual. There is a necessary place for the ‘coming out’ narrative, and there have been much greater authors than I who continue to write wonderful books about that. It’s just not what my books are about. I want to see them live.”

In the book, Hugo explains to Wallace that he chooses to stay at the tea house because of the “awe” on people’s faces when they finally go through the door.

“I am, at best, a lazy agnostic when it comes to faith,” TJ concedes. “I don’t know what’s on the other side of that door. I don’t know if there’s nothing or everything. I would like to believe that the people we love are never truly gone. The rational part of me wonders: if there is a higher power that watches over all of us, why is there so much suffering?

Advertisement

“Why is there so much pain and anger and anguish? That, to me, just doesn’t really make sense. For all I know, I will get to a tea shop with these wonderful, empathetic people. Maybe I’d be too scared to go through a door, or maybe I would be ready to go with my head held high. If I’m taken to a tea shop like the one in this book, I think I’ll realise that everything will be fine.”

Since his latest offering has been shared with the world, the writer has been inundated with letters and emails from those suffering through grief.

“I truly love that they feel comfortable to write to me,” he says, “because it’s almost like therapy in a way. There’s something cathartic about spilling your secrets to a stranger, because you don’t know them. People who email me are just looking for an outlet. It’s not my place to tell them how to grieve.

“There’s always the idea that no matter what kind of a platitude I’ll give, it’ll fall flat. Some people just want to be heard. They just want to be listened to. When I get those messages, I’ll write back and say thank you for sharing your story, and I hope that you can find a reason to smile at that person’s memory again one day.

“I don’t say: ‘This is what works for me’. Grief affects everybody differently, so I don’t try to take anything away from them. Their grief is theirs and theirs alone. There’s an act of catharsis in sharing. It might not fix anything but you feel a bit better, at least for a little while.”

Klune sees the book as offering some sense of emotional respite.

“Under The Whispering Door is a shoulder to lean on, if you need it,” he concludes, softly. “It’s somebody to tell you that sometimes it’s okay not to be okay, so long as you don’t let it become all that you know. You can feel down, you can feel angry, you can feel sad. That is perfectly within your right, but don’t let that define the rest of your life.”

Advertisement

• Under The Whispering Door is out now via Tor (Macmillan). Stay tuned for a queer retelling of Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio next year.