- Opinion

- 31 May 22

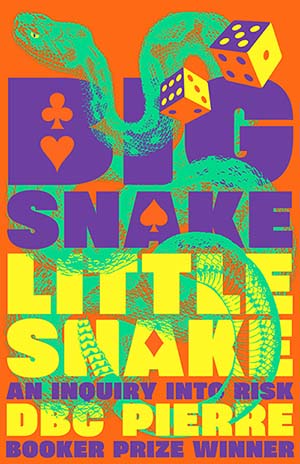

Interview: DBC Pierre on Big Snake Little Snake, Universal Odds, Quantum Physics, and Winning The Lotto!

He’s won the Booker. He’s won the Whitbread. But can DBC Pierre (aka Peter Warren Finlay), and his latest book Big Snake Little Snake: An Inquiry Into Risk, help Pat Carty win the Lotto? In a parallel universe, perhaps.

DBC Pierre – the initials stand for Dirty But Clean, a nod to his acting-the-donkey past – is the renowned author of several books, although his first, the multi-prize winning Vernon God Little, is probably still his best known. Let’s let him introduce the new one.

“The estate of Francis Bacon decided to spend some of their funds on a new publishing house called Cheerio,” DBC explains. “They wanted films and books on subjects which would have interested Bacon himself. I was approached to do something on the theme of gambling. I thought it would just be a collection of gambling stories, but I got more and more interested in the notion of odds and the everyday.”

There are snakes in the title – and a parrot in the mix that Pierre goes to Trinidad to make a short film about - but these are oviparous MacGuffins. This is not fiction, rather what has been described as a “cascade of true stories”.

“I could have led the book with any of those gambling stories,” Pierre says, “because they all have relevance to the way outrageous fortune works every day – but I was fascinated by this little snake turning up on the day I was told to gamble on the symbol little snake, so it seemed a good place to kick off and riff from.”

In Trinidad, apparently, they have a lottery game where symbols correspond to numbers. Pierre finds the snake and then buys a corresponding ticket – and wins. Does this mean if I walk past number 23 down the road I should then add that to my lotto numbers?

“It is the MacGuffin,” he admits, “but it was a little snake. I walk past number 23 everyday but I’ve never had a little snake come to my door.”

A two is like a snake, I say, drawing one out in the air.

“I know what you mean. Of course we can connect everything. There’s a fine line between magical thinking and mathematics. I guess I ended up focusing on coincidence-rich environments which I labelled as vivid maths. Certain times or places where the Kismet is greater than normal, you can almost feel it in the air. I was looking out for the weird shit because of the little snake and because of the place – which is so rich with stuff happening that we’re not used to.”

Limitations Of The Binary

Kismet means fate or destiny – what was meant to be. Is this particular type of magic more likely to present itself in a natural environment like Trinidad than in the middle of the city?

“I’m still thinking this one through,” he says, before preaching to the choir. “Ireland has a strong relationship with kismet and outrageous fortune. It’s a question of connections, either among people or in nature. For instance, I don’t find New York a particularly coincidental city because people don’t mingle. Ireland has a tight society."

“Trinidad has genetic strategies, some of the weirdest creatures that exist nowhere else – and there are still ones we haven’t discovered. It has a background of magic and folklore. Things are done slightly differently. The people have a tradition of looking to nature instead of looking to numbers, respecting the forces around them. That would be true in Leitrim where you’ll have the tradition of a healer.”

Originally from Australia, Pierre has spent many a night in Leitrim.

“There’s no scientific basis,” he says, “but still amazing things happen, and people respect that shit. Numbers on paper cannot express what we’re seeing every day around us. So maybe you’re right, when you walk down the street, if we turn a thing into a significant icon, perhaps it does belong to our magic.”

Ireland, like many other places, has turned away from the world of healers and magic. Have we lost something?

“I feel we have,” he agrees. “This dawned on me while I thinking through the book. The whole world is headed towards this binary numbers kind of autocracy and we’re missing the clues and the keys all around us. I come from a scientific family, I believe in science – but we’ve got all these tools in between us and the real world now, trying to interpret things as if we just landed on the planet. And the point is, we’ve lived here as homo sapiens for 300,000 years, we know exactly what the odds are. But we’ve given that all over to business. They’re selling us the answers, and they’re selling us the wrong answers.”

The Quantum Realm

I should point out that the book, which suggests that luck and chance are streams we might possibly tap into if we open ourselves up more to what’s going on around us, is both fascinating and funny, and skids gloriously all over the place. Take quantum mechanics, for example. Highfaluting stuff I know, but I’m sure there’s a pop star discussing their feelings somewhere else in the magazine if you’re feeling nervous. Check this out.

Hugh Everett III’s Relative State Formulation – also known as the Many-Worlds interpretation – gets around what Einstein called the “spooky action” of quantum entanglement, ie. particles in two places acting as one, by saying there can be no distance between them, despite the fact that it might appear to us that they’re a billion light years apart. SIT UP STRAIGHT AT THE BACK. This means they’re in the same place.

The Relative State Formulation says they’re in parallel worlds where each possibility becomes a universe of its own. Wait for it. Pierre sees this as meaning “we can’t die, essentially because at least one probability would always lead to our survival.” Good news, right? My head hurts. I’m going for a lie down. I’ll let Pierre take over.

“That is now a mainstream theory of physics, although it’s not to say we would be conscious of the shifting universes.”

“Boo!” I moan from the couch, as I apply a wet towel to my head.

“In 1953 when Everett wrote that theory, he was rubbished so much by the academic world, that he left physics forever. In the last few years, that and other multiverse theories have come to the mainstream because they bumped into a problem at CERN, where a test on the weight of a particle would dictate if we lived in a standard model universe or a multiverse. It came in absolutely in the middle so the odds are closed we’re in a multiverse."

“They’ve actually shut CERN down to rebuild it to do the next experiment,” he adds. “The last astrophysicist I spoke to is convinced it’s a multiverse. It explains the weirdness of some things in physics which still don’t add up. Ghosts and telepathy and all the stuff, which is currently nonsensical and paranormal, there are beginning to be theories explaining that as the seam between universes occasionally oscillating a little bit. We’re coming into a fascinating time, if we don’t blow ourselves up.”

You don’t get much of this kind of sport in Ireland’s Eye. Just to be part of the conversation I lob in Duncan MacDougall’s ropey 21 grams experiment, and his hypothesis that souls have physical weight. Is that us heading off somewhere else?

“Who knows? Nice idea,” Pierre replies, agreeably enough. “If you believe we’re in a universe where energy cannot be created or destroyed… Einstein admitted that time travel was absolutely possible, but only back to the moment you built the first time machine, because he had a theory that there is a point at which the universe does not want you to know the rest of the secrets."

“Quantum is doing that to us. As soon as we observe something, it changes, it doesn’t want to be observed. Our biggest problem is finding ways to observe them without particles knowing they’re being observed.”

Quantum Theory 101: Observation Affects Reality.

Pierre uses a busking Calypso musician – called The Mighty Viper, because it’s all connected – to illustrate Schrodinger’s thought experiment involving a cat in a box with some poison. Until we open the box and observe the cat, the cat is both dead and alive. Bollocks of the highest order, surely?

“Schrodinger proposed that experiment to show how stupid the idea was – he wasn’t doing it to prove anything. He was answering Heisenberg and Bohr, who said particles are both positive and negative until you observe one, at which point they choose. That ended up actually being true. Of course the cat is either one thing or the other, but in the quantum world, it is true that the particles don’t choose an outcome until they have to, until you watch them.”

Pierre likens it to a scratch card in his book, which is both a winner and a loser until we scrape off the foil. Rot of the brownest hue, undoubtedly?

“Of course the number is printed on there, but from our point of view…” he muses. “It’s fun to apply it to everyday life but, in truth, quantum physicists who deal with the madness of this all their lives do draw a line called decoherence.”

That’s where a quantum system, when not perfectly isolated, loses quantum behaviour.

“It decoheres into our reality,” DBC says, “which is fixed and unchangeable, apparently. They don’t follow it through and say it can be applied to gambling, but the ideas can, which are interesting.”

This is interesting. As in: I am “interested” in making money thanks to recent developments in my reality, but before we leave the quantum realm behind, I refer to the story Pierre tells about top Quantum man Niels Bohr being gifted a house beside the Carlsberg Brewery, with a tap running straight into the living room, after which his work took wing altogether. In a similar vein, in the book, Pierre starts talking about opalescence after several beers, and hits on another theory when he and his mates are hammered at a Chutney music festival, at lunchtime. A lot of these theories seem to have a few jars on board.

“That Niels Bohr chapter opens with the sciences stepping back a little bit on its condemnation of alcohol and drugs,” Pierre replies with a smile. “The problem is our conscious minds are so ridiculous and so nervous and focused on different stuff. Just shutting that down a little bit allows much more sensible ideas to come through."

“We’re a culture who’s always been able to benefit from at least some amount of drink,” he continues. “And the fact that Niels Bohr did his best stuff with a pipeline of beer, I thought was quite cool. It’s not something they teach you in school. Bohr also said, after quite some work, that nobody understands quantum mechanics, so we have as much possibility to imagine and riff on these ideas as many scientists, up to a certain point.”

The Lord knows I could talk about beer and, to a lesser extent, Quantum Physics all day long, and often do, but that’s not going to pay the rent. Pierre’s guide to plugging into the cascades of the vivid maths of the natural world to get our heads around gambling and risk should surely help me to the magic numbers and deserved wealth. Here are the points I took from the book, and Pierre’s reaction to them.

Trust Symbols

There is currently a picture of two boats behind Pierre’s head. If I take this as a sign, go to the track tomorrow, and bet the house on a horse called ‘Two Boats’, or some variation on those words, and the nag romps home, this is surely a coincidence rather than me tapping into magic?

“It is a coincidence,” he smiles. “Psychology would call that a disorder, to think of everything in magical terms. We pick our symbols anyway, we elevate some and don’t elevate others. It’s a natural function. The Lotto is a very mathematically improbable game. Horse racing is easier. A proponent of infinity calculated that if we played every Lotto draw, our odds were a win about every 30,000 years, although someone will play tonight and win it. ”

That's a big number. Perhaps we can frame the question differently: is there a way you can become that someone?

Willing It to Win

In one episode, Pierre buys a ticket when he’s down to his last few dollars and wills it, intensely, to win, and it does! Can I do this? If I think about it hard enough, might I make the result happen?

“The book asks that question, and I certainly wonder. Every month, science is, I think, inching closer and closer to saying yes. For decades, our intelligence services have been training people to use telepathy. If I really wanted to crack a lottery, I would be inclined to try and make myself dream it."

“I do this when I’m in a tight place with a novel,” he elaborates. “Before I go to bed I visualise the page and visualise things working out fine and I wake up, more often than not, with a new way forward. You could will yourself to dream of looking at the ticket and the numbers and then wake up and jot them down."

“Here’s a second problem; there is no time in physics. There’s certainly no time in quantum mechanics. Everything is happening at once, so they will be the correct numbers, but we don’t know when.”

So I’d have to play them for 30,000 years?

“We could visualise seeing the winning numbers in tomorrow’s paper. The thing is, I’m quite scientific, I like science. But those of us who were around before, let’s say, the 2000s, when life was still pretty analogue, know that shit goes on which is unusual. We know there are environments quite rich with coincidence and weirdness. We don’t talk about it because it’s unexplainable, for the time being, but we know that science can’t answer the actual nature of life. It’s more magical and mysterious than we think and maybe if we can make friends with it, we will be lucky.”

The Mathematics Of Music

This makes me think about music, and the magic of music, which cannot be explained by notes on a page, no matter how expertly written they might be.

“Yes,” Pierre agrees. “We’re tuned to mathematics. It’s a mathematical language but you’re right, it’s fascinating how we respond. They’ll explain it’s because rhythm equals heartbeat, but no, we’re talking about tone and how the notes follow each other. I’m the same with music, I can hear a certain note across the street or across a room, and immediately get a shiver, and there’s no real explanation.”

Stating that there’s a mathematical relationship between the first, the fourth, and the fifth does not explain why I want to jump up and down or cry.

“It’s true. We have to remember, mathematics is an invention, the universe might not be using the same mathematics, but it’s what we’ve invented to try and figure it out.”

Mathematics – and physics, quantum or otherwise – are our inventions to try and put order on chaos?

“Exactly. I think we’re getting to the limits of what the universe will let us know. CERN will open back up for the next level of experiments and we’ll see what happens, but we can say the universe doesn’t want that information to be known. It’s making it difficult.”

CERN starts running, and everything melts down to a massive GAME OVER sign.

“They divide by zero, and we all go down the spout!,” Pierre jokes (I hope). “That’s what they said would happen the first time. It’s not likely, but the possibility is never zero that it will happen.”

My thoughts would be these: if there’s a chance, even a tiny one, of breaking reality, then don’t turn the bloody thing on.

“I tell you what, if we’re in a multiverse, that’s gonna be a hard one to explain in the tabloids. The first thing it would mean is that the study of physics is pretty much over because there’s nothing to say that each universe won’t have its own laws. We’re only in one of them. It’s a mind expander,” Pierre adds, with galactic understatement.

The centre cannot hold, mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, and I still don’t have my winning numbers.

The Long Odds

Throughout the book, Pierre talks of the astronomical odds of us being here at all. If electrons were even slightly bigger, we wouldn’t have even started, etc. The universe believes in long odds, but he tells me not to buy a quick pick, because those odds are just too long. What’s the difference between me picking 1,2,3,4,5,6, or selecting numbers cause I saw a snake or a number on a door?

“Lotteries can be rigged, so we’re not dealing with pure odds. There’s more than one guy who has actually won the jackpot two or three times and it’s those guys who say quick picks are bad deals. It could be that the system limits jackpots and then it only has to deal with the ones we write ourselves or it could be some other reason. I’m not sure their system would be truly random. I would try ‘willing’ the numbers.”

This takes us back a few steps, we’ve slid down one of the snakes.

“Fortune favours the brave!” Pierre insists. “We don’t realise that the biggest risk is no risk. We think that doing nothing is the most stable position but a lot of things that happen to us require something to be done. We should meet those moments with calm, assertive energy. Put any fears to the back of your mind and move forward with your first and best idea. I do believe that favours good outcomes. Keep moving forward. I believe locomotion does bring luck.”

To summarise then, the universe has cascades of magic, and I can know these things if I open myself up to it.

“Yes. Sit quietly and watch and think about stuff. We had such a bad time in the pandemic and lots of people are grieving, which is terrible, but for those of us who survived and had to give up the routine, I was impressed with how much more sense everything made when I just sat quietly and watched and thought about stuff."

“We’re not trained to do that anymore. We look for answers immediately, through the internet or some kind of product, or we simply distract ourselves onto something else. We’ve been primed into this fucking anxiety. I worry for youngsters. The best outcome they can expect is that their fitness watch interprets panic attacks as exercise."

“Just sitting still for a while everyday brought a whole different sense. You really just imagine you’re the last person left on the planet and it all makes a tremendous sense. We get occasional storms, and there are volcanoes and earthquakes, but generally speaking we’re in a very lucky place and not much happens that we cannot respond to.”

There you go. I suppose I don’t need the lotto because, in a way, we’ve all already won it. Sort of.

• Big Snake Little Snake: An Inquiry Into Risk is published by Cheerio

RELATED

- Opinion

- 17 Dec 25

The Year in Culture: That's Entertainment (And Politics)

- Opinion

- 16 Dec 25

The Irish language's rising profile: More than the cúpla focal?

- Opinion

- 13 Dec 25