- Opinion

- 25 Jun 19

Interview: Joseph O'Connor on Shadowplay and Bram Stoker

The new novel from Joseph O’Connor, Shadowplay, is a fascinating exploration of Bram Stoker’s life in Victorian London and the unique manage-a-trois that was at the heart of it.

No stranger to historical fiction - Star Of The Sea detailed the Atlantic crossing of the titular famine ship and its sequel of sorts, Redemption Falls, led the reader across an America ravaged by civil war - or imagined literary biography - he detailed the doomed romance of John Millington Synge and Molly Allgood in Ghost Light - Joseph O’Connor’s Shadowplay conjures the Victorian London that begat Bram Stoker’s most famous work, and the relationship between Stoker and the then most famous actors on the English Stage, John Irving and Ellen Terry. Slightly delayed due to an event with the Swedish royal family - Hot Press has been handed worse excuses - I asked O’Connor, once we were settled, what initially attracted him to Stoker?

“He is somebody who has always intrigued me, he's the first Irish author I ever heard about as a young child” says O’Connor. “My maternal grandmother, who lived on Keeper Road, had a great stock and store of Ghost stories. Dublin ghost stories about Marsh's library being haunted and how if you walk around the Pepper Canister church three times you see the devil, and all the stories about the haunted English Stately homes. There was a particular one, The Brown Lady Of Raynham Hall, which is in Essex, and she was the first ghost who was ever photographed, in a brilliant forgery! My grandmother used to talk about how an ancestor of hers who had been a lamplighter in Victorian Dublin had met Stoker, and knew him a bit. Stoker was a great night-walker. I was quite intrigued by that notion that someone belonging to me had met this great author. I didn't quite see him as one of the extended family but I thought there was some kind of loose connection. It's also the fact that he wasn't celebrated. There are buildings and streets and bridges named after Joyce and Beckett. Even on the poster, which is now very controversial of "The Great Irish Writers" - it's all men, which is why people don't like it so much - Stoker doesn't appear.”

He did warrant one of those plaques, I offer. “There's a couple of plaques now on the places that he lived, but you know what I mean, when people talk about the pantheon of Irish writers, he's a bit forgotten about.”

Is he perhaps looked down on as ‘popular literature'?

“Possibly, although Dracula is also a great technical piece of writing. It is so clever in the way it approaches the reader and the different kind of registers of language it uses. I think it's partly that he, and this is one of the intriguing things about him, wasn't that interested in Ireland. It's amazing to think of a writer coming of age in the 1880's and the 1890's, Yeats and Lady Gregory and Synge are getting going in The Abbey, and there's all that flowering of cultural nationalism.”

Stoker takes a well-aimed swipe at Yeats and The Golden Dawn crowd, the quasi-mystical order that Yeats was a member of for over thirty years, in the novel.

“Well that's my imagining of it, he doesn't get it, he's just not interested” O’Connor counters. “It's sort of like the way The Boomtown Rats didn't want to be a show band, they wanted to go off to London and make it big. And with my image of Bram - and it is a novel, it's my version of him - I think it's fascinating that he wanted to fly by all of that and emigrate in a way that even Joyce didn't. I mean Joyce left, but he wrote about Ireland for the rest of his life. Stoker just wanted to do other things. There are silences around his own life, we know very little about him, he published an incredibly long book, the Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving, which is like a kind of snowstorm of facts, partially designed to blind you."

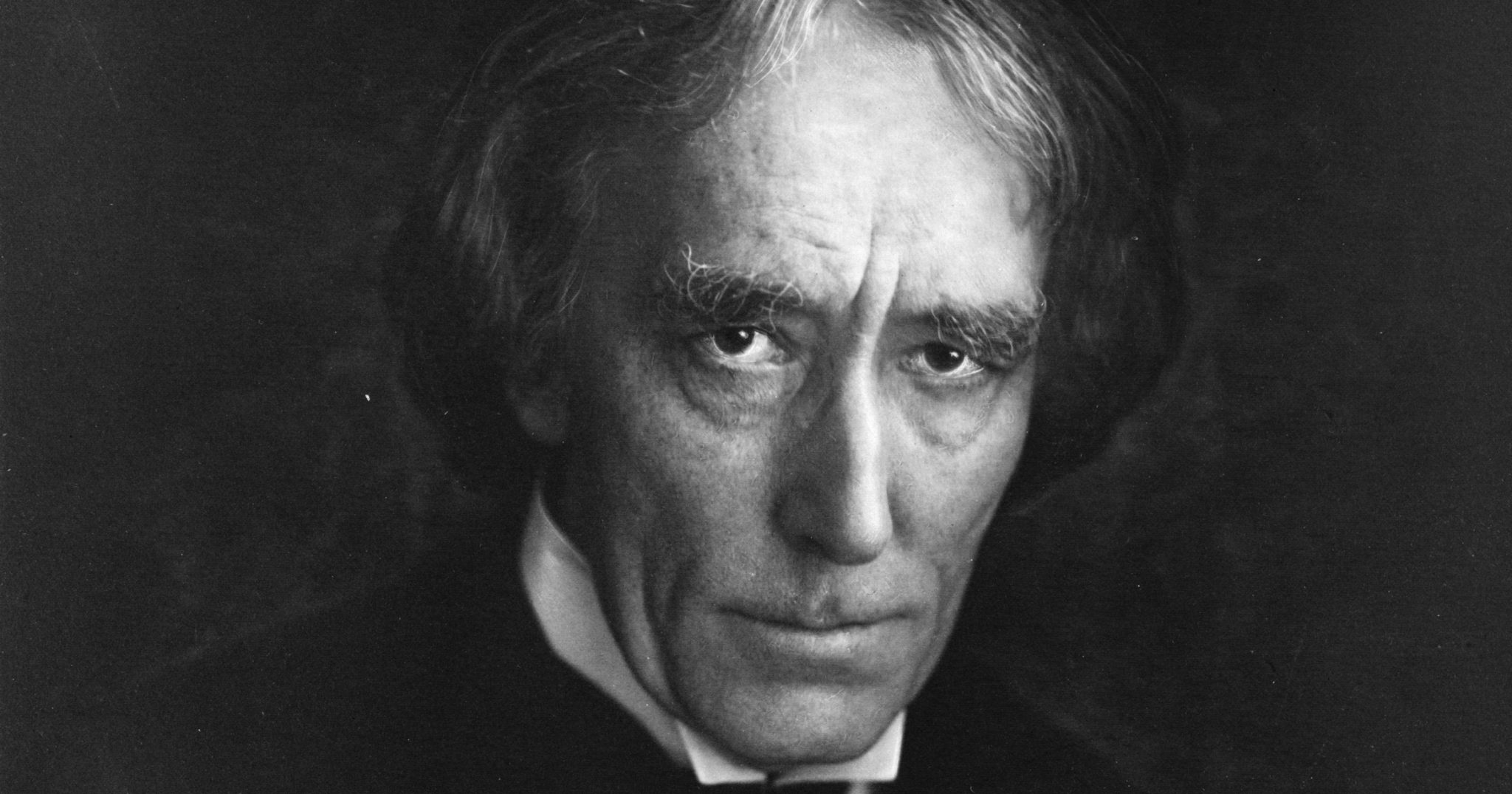

Henry Irving was perhaps the most prominent stage actor of the Victorian era. Stoker, moon lighting as a theatre critic for the Dublin Evening Mail, penned a favourable review of Irving’s Hamlet at Dublin’s Theatre Royal, which resulted in Irving offering Stoker the position of manager at his Lyceum Theatre in London, a position that Stoker would hold for close to three decades.

O'Connor continues. "He tells you everybody who was there at every first night, what was on the menu, what the wines were, all of that - a hugely long detailed book revealing almost nothing about himself and the relationship with Irving. So the very silence around it I always found intriguing.”

Henry Irving

Henry Irving

Stoker appears to have been in favour of the British Commonwealth and one could argue that Dracula sits along the contemporary work of H.G. Wells and others as a “defending the empire” novel, repelling invasion from outside forces.

“You could tie Dracula to anything, which is an amazing thing about the book and the character, he's subtle enough and supple enough to project anything onto. I was reading this morning at an event that was about famine and emigration, and one of the questions was 'Is Dracula secretly a famine novel?', is Dracula a metaphor for famine, and I had no doubt that I could find you a PhD thesis somewhere where somebody says that. As a character he is a kind of theatre in which people stage their own plays. You can make Dracula mean whatever you want. And that's part of the genius I suppose, he's a character who is able to live for anybody, no matter what perspective you're coming from.”

The Children Of The Night. What Music They Make.

O’Connor mentioned the holes in Stoker’s life and one theory is that he was a closet homosexual. A lot of evidence in Shadowplay points in this direction whether it be the relationship with Irving or Stoker’s discomfort when Oscar Wilde visits the theatre – Wilde’s libel case against the Marquess of Queensbury which would eventually leads to Wilde’s arrest and prosecution took place in 1895.

“Well it isn't evidence because it's made up, "O'Connor puts me straight. "But you could read it that way. I don't know, but I'll tell you the facts, which are that Irving and Stoker's relationship was far more than a friendship. It was ardent and intensely emotional.”

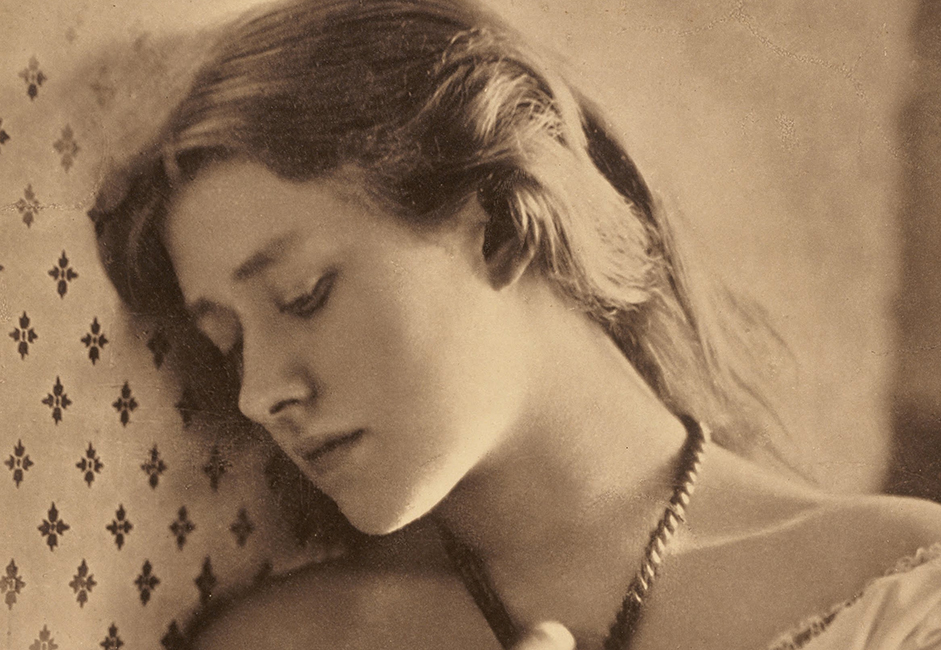

There’s a scene in the novel where Stoker stumbles across Irving and the actress Ellen Terry - a famous beauty, then England’s highest paid actress, and Shadowplay’s other main character – in bed together. Is Stoker more envious in this situation of Irving or Terry?

“Well the reader will have to decide, maybe it should have been the three of them!” O’Connor replies with a grin. “The facts are that the relationship was very fiery and tempestuous. They used the word love about each other and they signed their letters to each other with eternal love, and Stoker says in his book that he and Irving were closer than it's possible for spouses to be. They use very emotionally ardent language when they're talking about and to each other, but I think that in the late Victorian era before the Wilde trial kind of codified things and criminalised things that relationships between men were a bit looser than we think and that there was a licence to express all of those feelings and emotions in a way that wasn't very directly sexual. I also think, and it’s just my take on the three characters, Ellen as well as Irving and Stoker, that they had a particular notion of sexuality as a kind of current that is always on. I think they felt that a portrayal in a play could be sexual or having a conversation with somebody could be sexual, or the scene where they're trying on the saris. There are so many aspects of life that are tinged with sexuality. I suppose it's what Freud began to say in the 1910s and 20s but I think that these three characters had an awareness of that which was a bit ahead of their time and that they're able to plug in and out of that current.”

Is that endemic of the bohemian, theatre crowd? A character at the start of the novel refers to the theatre as Lucifer's recruiting station, that's the outside view of the theatre life.

“Oh yeah, I think that is fact. Even a bit later, say in the era of John Synge, who I wrote a novel about, Ghost Light, he's kind of 1910, his family were very orthodox biblical protestants. None of them ever set foot in a theatre, no member of his family ever saw one of Synge's plays performed, and I think the idea was a hangover from Victorian notions that the theatre was a very disreputable place. In the past you had boys dressed as women, sexual identities were quite fluid in that world. There's a specific couple of biblical verses having to do with the worship of idols that people would often quote as a reason why you shouldn't go to the theatre.”

And there's a history in England of closing the theatre down on moral grounds.

“Absolutely and it is definitely a fact that at the start of Irving's career, the theatre was still see by the establishment as a bit dodgy, and his mission was to make theatre respectable. He was the first actor to be knighted so he did achieve that with Bram and Ellen by his side. But the theatre was a rough, tough place. It was one of the few places where young men and women could meet at all, in an unsupervised way, so I think it probably did attract people who were sexually unconventional.”

Stoker accepts Irving’s job offer without hesitation, an indication of how unhappy he was with his Dublin civil services life.

“Irving does what Dracula does, step in, I can't invite you, you have to step into the scene” O’Connor explains. “There are other intriguing things that demonstrate Stoker's knowledge of what we would now call gay culture. As a young man he wrote a number of letters to Walt Whitman which are intriguing and I paraphrase them in the novel where he says to Whitman "when I first read you as a student I thought that I was alone, I thought that people of my sort were unique, I thought that I might be the only one of this sort in the world, to be despised. And now I read your work and could understand there were many of us" so is "my sort" just adolescent loneliness or did he mean something else? We don't know."

You can see Whitman, and Irving in particular, as almost rock n' roll stars of the time, those letters to Whitman could be someone writing to the likes of Morrissey in another age.

“There's no doubt, Stoker idolised Irving. I think Irving was the great love of his life.”

When Stoker acquires a typewriter in the text he imagines that “with this I could be anyone”. Although he’s not mentioned in the book, Stoker was close friends with the author Hall Caine, whose The Eternal City was the first novel to sell a million copies, while Stoker has to plead with a book shop to stock his work. Were his literary ambitions part of this unhappiness, this apparent longing to be someone else?

“I think a lot of writers do that!” laughs O’Connor. “I don't know if he wanted to be those people but I think he had what a lot of different artists have, and what a lot of people who had a troubled childhood have - a desire to leave a mark. I think Bram wants to be somebody, I don't think he necessarily wants to be Irving, I don't think he wants to be a rock n roller, but he doesn't want to go through life without anyone ever noticing that he's been here, that's why I sense there was a restlessness to the creativity. Of course part of it was a desire to create something beautiful. I think it was also the desire for financial freedom from having to work in the Lyceum, it's a difficult thing to have a well-paid job that you don't really like.”

A love/hate relationship with his day job, "I love the theatre, but I want the freedom for other pursuits"?

“I think he wanted to do all of those things, I don't think he hated the job, I think love/hate would be a bit strong, I think he became addicted to the theatre, and to Irving's mission in a way that probably took away from the time that he had for his own work and his own life and his family and all of that. But at the same time, given the choice of being a Dublin clerk, or hanging out with the Mick Jagger of Victorian theatre, I can understand why he made the choice that he did. I think he also was, like pretty much everyone who ever met her, just enthralled with Ellen Terry.”

Enthralled by her physical beauty?

“No, I think it was her artistry and her independence. She's the highest paid woman in England, she's a lot of freedom, she's very unconventional, and she's the only real-life person that he mentions by name in Dracula where she's a kind of metaphor of beauty. A character is getting married, and I paraphrase this in the novel, he describes how he said to his fiancée "if Ellen Terry won't have me, maybe you will?" It's an amazing thing for an author to do, to put in the name of somebody he knows, a close friend, in that particular way. I think there's a lot of electricity going on between the three of them.”

Ellen Terry

Ellen Terry

Though it is as O’Connor says an imagining, there are several clues about the formation of Dracula in Shadowplay. Whitby Bay, New Orleans, Jack The Ripper, a character Renfieldly eating insects, Stoker’s longing to “roam at will like a man made of fog” and even Punch Magazine describing Stoker as “The Irish Vampire”. Are these elements included to drive O’Connor’s narrative or are they true to Stoker’s life?

“The Whitby aspect of Stoker's life, and Whitby's role in Dracula are quite well documented.” O’ Connor states. “Thanks to the Victorian mania for information gathering we actually know the dates that Bram was in the library in Whitby and the books that he borrowed, and the particular passages that he underlined and all of that. Whitby is a very important part of Dracula. So it's a mix of that and I suppose conjecture. As a novelist myself, I think how novelists work, and it's not in terms of role models. I don't think Bram looked at Irving and said 'ok, I'm going to change the name and you're going to be Dracula'. I think a kind of osmosis happened where he took maybe one aspect of Irving or Ellen or something he heard or saw in the street, his sense of London at that time. So if you think that's true then I suppose when you read about a two-year period when The Ripper was at large, it's hard to believe that it wouldn't have affected Bram in some way. I don't have the textual evidence for it but it's very striking that the moments when Dracula becomes really frightening as a novel are not the scenes in Transylvania, it is when he comes to London, when he's going around the city in disguise. He could be sitting beside you on the tram, he could be walking past you in Leicester Square. So some of the language, some of the characterisations feel very similar to what people were saying about Jack the Ripper, and it's my conjecture of how all of those elements in ferment might have created the situation out of which Dracula came to be.”

Might Stoker have been thinking that by incorporating contemporary elements like The Ripper and the worsening London Fog, he could score a hit?

“Perhaps, yeah” O Connor reckons. “There is a scene, as you know, where Irving is far more mercenary than that, he says 'let's just do it, let's do Jack the Ripper on stage'. The novel tries to address the moral ambiguity of writing about these things at all.”

Throughout the novel Stoker wonders if they might get a play out of a lot of things.

“I know a lot of writers like that, and I'm probably one of them!”

With the antenna out all the time?

“Pretty much. When I teach, as I do at University of Limerick, I'm always saying to the students something that McGahern said about writing which is that style can be learned, to write a beautiful sentence can be learned, but the first thing a writer needs is a way of seeing. You just look at the world in a different way to other people and you keep your eyes and ears open all the time. It is tiring and tiresome but you're constantly thinking could I do something with that, and that's my sense of Bram because the books keep coming and they're not particularly successful. I just have this feel for his restlessness at the same time and his heroic insistence on just carrying on. Maybe I'll stumble into something great, and he did.”

What about the afterlife, if you will, that Dracula has enjoyed? Once motion pictures come along, the novel takes off, and it never goes out of print. Everybody in the world knows the name Dracula. Is it ironic almost how successful it became, given that he's seems embarrassed by the subject matter in your book. Everything Stoker wanted came along after he died.

“Yes, everything he wanted came after and it terms of story telling, that's a lot of fun because the reader has a crucial part of the story that no one in the book has, so it's bit like the pantomime thing, you want to reach into the book and grab Bram by the lapels and say it's gonna be fine, it's gonna be ok. His reticence about copyrighting his work might be what you mean about not taking it seriously. I think he did have a kind of defence mechanism which again a lot of authors would have and I probably had when I was young, but if people don't like it it's fine, if I don't like it, it's fine, I'm going to write another one. A writer has to come up with strategies just to keep it going, it's a really hard set of ambitions to have and it's probably not going to work out, so I think writers are quite good at strategies of denial in order to just keep going at all. I think one of Bram's was 'ah sure I don’t really mean it, I have a very well paid job in the theatre and it's just a little hobby thing that I do.'"

The reader can point tot Irving and Hall Caine, knowing they'll never achieve the immortality that Stoker will enjoy.

“It's amazing, Hall Caine sold millions, people used to buy statues of his head. There's a statue of Henry Irving on Charing Cross Road, theatre people actually do remember him. I met Barry McGovern last week, he’s doing the audiobook of Shadowplay, and he has a really encyclopaedic knowledge of Irving. So actors remember him, but the public doesn't, and Ellen Terry has been forgotten about though Stoker spent his life in their shadow.”

Anything associated with Dracula and vampires has a built-in audience these days. Hot Press asks, while making the internationally recognisable rubbing-fingers-together-cash gesture, if this was on O’Connor’s mind at all.

“No it wasn't, and if it was I would deny it!” O’Connor laughs.

The Devil Is In The Detail

Shadowplay is an epistolary novel, like Dracula. We get different viewpoints in different formats such as letters, articles, and diary entries.

"That's something I've used before in my books, as far back as my third novel The Salesman, which I wrote not long after re-reading Dracula for the first time in a number of years. Dracula is a very important book to me, it's a regular pilgrimage. If you read John Steinbeck or Hemingway or any of the great writers or the books that were on our courses, it was the monolithic, authorial knowledgeable voice, and that's beautiful, but Dracula says ok, I'll give you first-person in chapter one and then in chapter three I might contradict that, and in chapter four I might have a transcript of an audio recording and chapter five might be a diary entry and that's a bit naughty because you shouldn't really be reading someone else's diary. Chapter seven might be a letter between two young lovers, and that's a bit naughty too, you shouldn't be reading someone's private letters. It's clever.”

It makes it more believable for the reader.

“Yes, it's more real and more textured and more of a reading experience where you're kind of half way through Dracula before you even notice. I used similar techniques in this book partly as a homage to Dracula but also because in the hope that it has the same effect.”

Was it something about the character of Dracula himself that you identified with straight away? This gothic, Byronic hero is always attractive, because we can't really live like that.

“I suppose it goes back to Lucifer as one of the oldest fictional characters we have, the idea of the devil being attractive.”

Milton’s Paradise Lost?

“Milton, yeah, rooting for the devil, the devil has all the best lines. It's brilliantly clever of Stoker to make Dracula like that. Of course you want him to be caught, and you want the stake through the heart and the whole thing, but the evil has come from broken love so there's a little naughty part of you that's cheering for Dracula, he's a bit more interesting than the slightly drippy guys who are trying to catch him. Another aspect is the amazing kind of modernity of the book. Stoker is absolutely not the first person to put a vampire in the heart of his story, but he is the first person to put him into the world of the contemporary reader. In Dracula there are telephones and audio recording. There are medical procedures and women's magazines, international travel. People think it's kind of set in this medieval Transylvania but Stoker is very avid to put the vampire into the world of the reader. It's a great novel of England and a great novel of London. Like many an Irish immigrant before him, Dracula's big dream is to go to London, make it big. “

Is that why the character has become so ingrained in our culture, because of this modernity?

"I think it's a big part of it, I think he wanted to take that ancient archetype and move it right into the reader's world so when you close the page, Dracula might be in your room. It's genuinely quite a frightening book, here and there."

Arthur Conan Doyle and Stoker were friends, and Doyle even offered a favourable review of Dracula. The detection methods that Sherlock Holmes employs appear current to us. Is the fact that these characters appear to have one foot in our times the reason why, with each decade, we get a new representation of Holmes and a new representation of Dracula?

“Sure, I'm speaking about the sexual identity of Victorian characters, and Holmes' relationship with Watson is open to all kinds of interpretation. What we love about Sherlock Holmes is the use of deduction and intellect, whereas Dracula is all about the darker side, what's going on in the shadows.”

There is a mention near the start of your book of Ricketty Kitties, it would be very remiss of me not to point out the similarity of this to The Radiators From Space's ‘Kitty Rickets’.

"Well, you will know that the Radiators from Space got it from Joyce and Ulysses. Kitty Rickets is one of the girls who work in the brothel owned by Bella Cohen in the night town sequence. So it's partly Joyce, it's partly The Radiators. The cover image of Ghostown - probably my favourite Irish record of all time, re-released this summer for its fortieth, I wrote one part of the liner notes for it - has a still from Nosferatu on it. I think The Radiators were very tapped into the tradition of ghostly, supernatural story telling, 'Faithful Departed' is a beautiful ghost story. One of the amazing things about Philip Chevron's writing is that, while he was a great punk rocker, he was a great Irish writer too. He tapped into the Irish stories but also the European tradition, cabaret and all of that. They were a hugely important band to me and I love them.”

Joseph O'Connor

Joseph O'Connor

I'm reaching for more rock n' roll connections, Florence Stoker writes her letters from an address on Cheyne Walk in Chelsea, the street that the rock n' roll vampire himself, Keith Richards, would one day call home.

“I actually didn't know that, it's a very beautiful street in London, it doesn't surprise me.”

Keith, at his height, was the personification of the gothic hero.

"Don't they say about Keith, and I'm sure it's an urban myth, that he went to a clinic in Switzerland every couple of years to have all of his blood transfused? I think there is a bit of rock n' roll in the book, certainly the live theatre scenes, that's my sense of what it would have been like to see Irving. The first time Bram goes to see him, it's kind of a Jim Morrison thing, the audience are going nuts. It's tapping into that era before theatre became respectable, you had to win over the audience and I think Irving loved spectacle and fireworks. He would have been glam rock.”

He's a bit of an arsehole.

“You've never heard of a rock star like that?” O’Connor smiles.

Shakespeare's The Tempest shows up at the end of the book, I can't quite remember the context.

“They see it in the cinema”

That play is all about artifice, Prospero putting away his books, "our revels now are ended, our actors were all spirits, we are such stuff as dreams are made on, art to enchant" it's theatre about theatre. Is it included for that reason?

“It's partly that, it's also Shakespeare's last play and my favourite. I find it very touching, very moving. I suppose I'm also gently teeing up the reader for what happens to Bram later on. I think it's the kind of theatre they were interested in. One of the reasons why George Bernard Shaw gets a bit of a kicking in the book is that while Shaw was an amazing artist, he and Ibsen and Strindberg had come along with the theory that the lives of ordinary people are worthy of celebrating in the theatre, you don't have to be princes or courageous or beautiful, and Irving and Bram and Ellen just don't believe that. They thought it should be about spectacle.”

'The depravities of this world are no matter for art.'?

“Yes. Irving says at another point that having to live real life is bad enough without having to pay to go to see it in the theatre. I think Bram believed a very particular thing about art which is that it should be spectacular and dramatic and theatrical and that it shouldn't reflect real life on the surface. But, in the course of telling a supernatural story, there would be little prickles of resonance that would take the reader away to this other place, but they still might say maybe Dracula is all about me.”

How would you respond to the opinion that Dracula is not a great book so much as it is a great character?

“Well I don't agree with that, the character is very strong, but the range of the narrative, the voices are brilliant. I think it's of its time, there are moments of kind of clunky sort of self-parody, it's full of orphans, a great trope of Victorian literature, because Stoker felt that if you had a father and mothers, you'd be morally so clear that you wouldn't make mistakes. He borrows things from other writers but still, at it's heart, there are three or four things about it that make it brilliant - the range of narrative voices, the modernity - nobody had ever thought of having a vampire story where the telephone rings before - and that particular blend of where the good and bad is in Dracula. Secretly, there's a little bit of you that is cheering for Dracula. It's not just black and white.”

Shadowplay is available now.