- Opinion

- 05 Jan 23

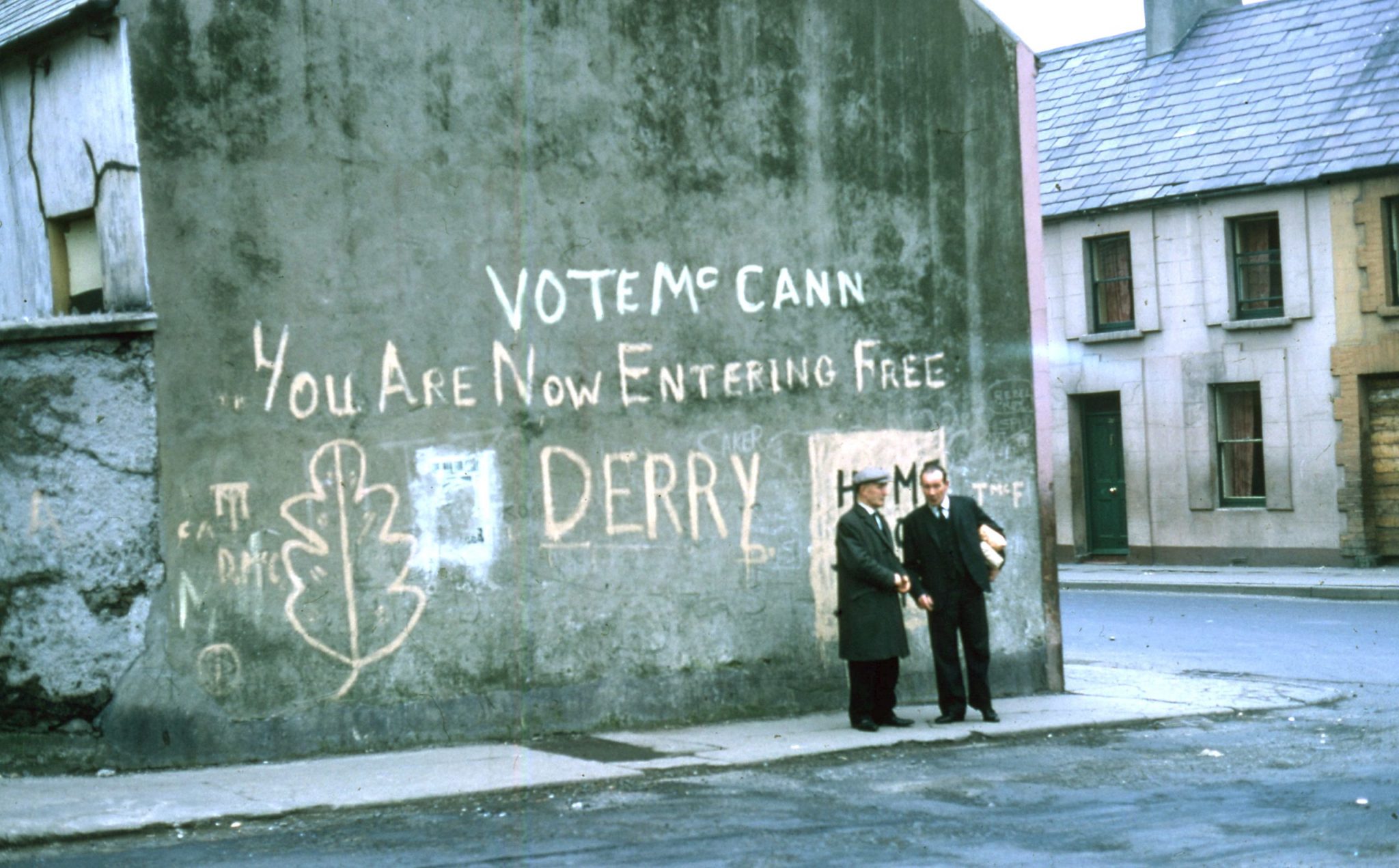

On January 5th 1969, the legend "You Are Now Entering Free Derry" was writ large on the gable wall of a house in Derry. It is still there, offering a powerful reminder that change had started in the North before the 'armed struggle’ bullied its way centre-stage. Eamonn McCann remembers the day...

January 5 marks the anniversary of the inscription of “You Are Now Entering Free Derry” on the gable wall of Johnny Kane’s house at the junction of Lecky Road and St. Columb’s Street in the Bogside.

Almost all of the of the adjacent houses have long since been demolished, leaving the Wall free-standing. Over the years the structure has assumed iconic status, the image of the lettering reproduced on pieces of art, political banners, t-shirts, tea towels and all manner of souvenir knick-knacks.

It is widely assumed that the words are intended to evoke the notion of “Irish freedom”, as traditionally understood. People must make what they will of slogans. But the Wall was intended as a monument to the civil rights movement which arose in the late 1960s as a shout of anger against the oppression inflicted on Catholics by the Orange State.

On New Year’s Day in 1969 a couple of hundred Left-wing students organised as People’s Democracy set off from Belfast City Hall to march across the Glenshane Pass to Derry. Attacks on the march along the way culminated in a ferocious assault by cudgel-carrying Loyalists and a squad of cops with batons drawn at Burntollet Bridge, about five miles out from the city. In the aftermath, the Bogside erupted.

In the early hours of January 5, exhaustion on all sides led to a lull. Resting rioters gathered on the piece of waste-land adjacent to the Kanes’ house. At around 3am, a suggestion was made, by myself, that we should paint “You Are Now Entering Free Derry” on the Kanes’ wall. It is easily the most enduring sentence I have ever come up with. But it wasn’t entirely original.

Advertisement

I had seen “You Are Now Entering Free Berkeley” in coverage of an occupation of Berkeley College in California demanding free speech for students frustrated by the rigid, conservative curriculum imposed on them by college authorities. The connection to student radicalism was important to many of us, as was the implicit association of our campaign with radical youth movements in faraway places.

Credit: Jim Davies. museumoffreederry.org

Credit: Jim Davies. museumoffreederry.orgSOMETHING HUGE HAPPENING

This was the moment of the youth-quake which unnerved ruling classes around the world. Protests against the Vietnam War and for black liberation suddenly swamped the streets. Revolution was on the agenda of millions of malcontents everywhere you looked.

May 1968 in France saw the biggest general strike in Europe since World War Two. The “Prague Spring” sent shudders through Stalinism. The women’s liberation movement stomped onto the stage. The Stonewall Riot in Greenwich Village catapulted gay rights into political discourse everywhere.

For people of a certain age, it can be difficult to see these events other than through a fine mist of nostalgic sentimentality. But there was a palpable sense of being part of something huge happening all over the world. “Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive/And to be young was very heaven.”

Advertisement

It isn’t all soppy remembrance of the rowdy days of imagined revolution. There were measurable gains from the sometimes incoherent events which preceded and followed on from the ornamentation of the Kanes’ gable.

The most glaring instance of sectarian discrimination lay in Derry where, election after election, a unionist minority “won” a majority of council seats, on the basis of ward boundaries drawn precisely to ensure this outcome. Plus, only householders could vote: it followed that to allocate a family a house was to put them on the electoral register. The local bosses of unionism had to be highly circumspect when it came to compiling the electoral roll.

IT WASN’T A GUNSHOT

Within two years of the painting of the Wall, Londonderry Corporation had been abolished and a “commission” appointed in its place. A raft of anti-discrimination laws was put in place. The Special Powers Act, which had given the police and army virtually untrammelled power to treat undesirables any way they wanted, had been erased from the statute book.

State bigotry, which had seemed set in stone down previous decades, was buckling under the pressure. This wasn’t the heady freedom which dreams had been made on. But it cleared the way towards brighter days.

We can usefully debate the hows and whys of the failure fully to realise these hopes. The most we can say with certainty is that there was nobody didn’t make mistakes. At this stage of the game, allocating blame would be pointless.

We can also say, looking back, that the civil rights movement, including its radical-Left component People’s Democracy, made more headway against sectarian oppression in the North than any other political formation operating at the time.

Advertisement

It wasn’t a gunshot or an electoral triumph which opened eyes to new possibilities after 50 years of stasis, but the writing on the wall of Johnny Kane’s house at an ungodly hour 54 years ago today.

This is worth remembering the next time you hear it said that the armed struggle had been inevitable, all other means of achieving change having been tried and had failed.