- Opinion

- 22 Oct 24

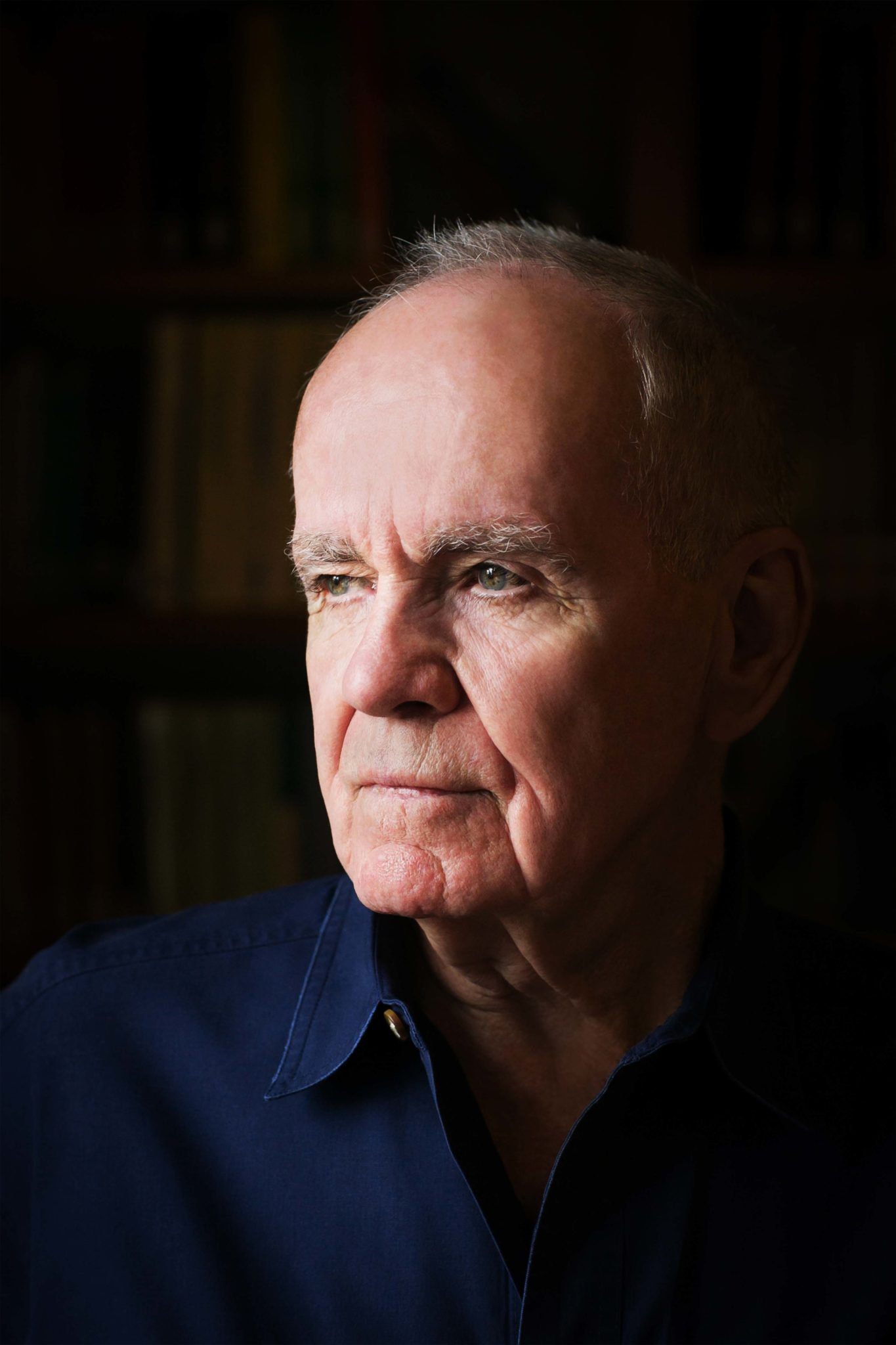

Celebrated author John Banville on his gripping new mystery The Drowned, Donna Tartt, Nabokov, and his friendship with late literary icons Cormac McCarthy and Martin Amis.

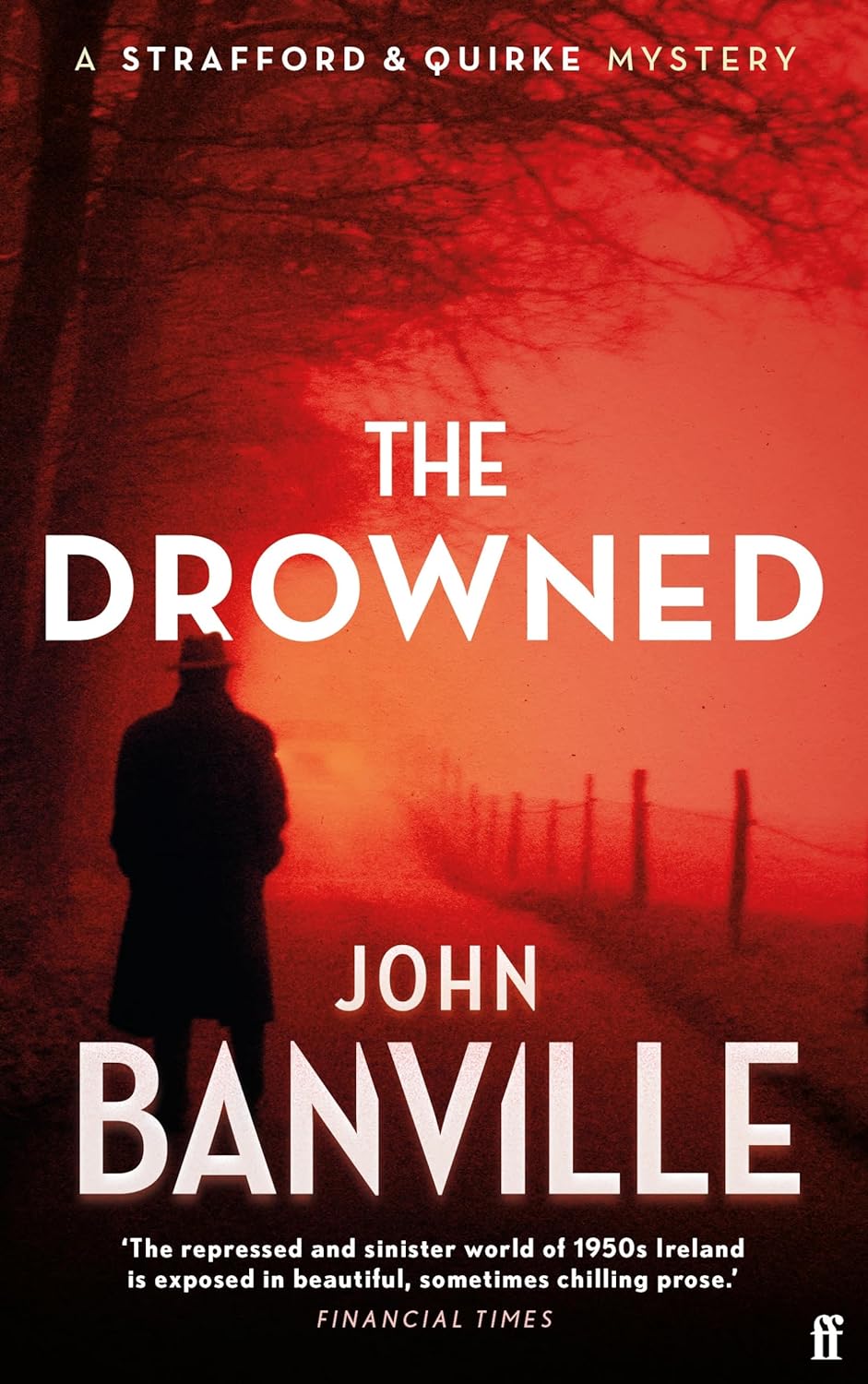

Set in 1950s rural Ireland, John Banville’s latest Strafford and Quirke mystery, The Drowned, begins with a man discovering a mysterious empty car in a field. Thus, the scene is set for a compelling missing persons case, as a husband claims his wife might have thrown herself into the sea.

Detective Inspector Strafford and the pathologist Quirke are soon the case, which unfolds with the usual gripping twists and turns. Of course, Wexford author Banville first made his name as one of Ireland’s most acclaimed literary novelists, earning rave reviews for the likes of 1989’s The Book Of Evidence and 2005’s Booker winning The Sea. His first crime novel, Christine Falls, was published in ’06 under the pen name Benjamin Black, though Banville now publishes them under his own name.

At an earlier stage in his career, could he ever have imagined he’d end up writing so many crime stories?

“I certainly wouldn’t,” says Banville. “If somebody had told me that I would one day write a book called The Black Eyed Blonde, I would’ve said you’re mad! I mean, I wrote the first one back in 2003 or '04, and I thought it was a one-off. But I got interested in the characters and I’ve stuck with them. Still, I wouldn’t have expected it.”

How do you get ideas for the stories?

Advertisement

“Oh god, I don’t know,” he responds. “It’s a sort of childish thing, I make them up. When we were kids, we made up stories and told them to ourselves, and that’s what I do with these. I try for spontaneity, I try not to plan and have everything plotted out beforehand. It’s funny, when I did the last one, The Lock Up, to make myself finish it, I went off to Annaghmakerrig for a week.

“I thought I’d finished it on a Friday evening, and I was leaving the next day at lunchtime. In the morning, I thought, ‘I don’t like that ending, or that killer.’ Then I remembered someone from earlier on in the book and I said, ‘No, he did it!’ So I sat down and wrote the last chapter in the morning, didn’t even read it, and sent it off. The point I’m making is spontaneity is all. My other books are planned and take years to write, but these are done quickly.”

A notable wrinkle in the story this time around is Quirke’s daughter, Phoebe, falling for Strafford – an ideal way to needle the irascible pathologist.

“Well, I like annoying Quirke cos he annoys me,” reflects Banville. “He’s an awful curmudgeon, he really is. I keep thinking I might kill him off. I think I killed off Hackett in the current one. Again, it’s a like a child playing with insects, you have absolute power over the characters. I can do anything with them I like. I can bring him back to life if I like. Georges Simenon frequently does that – he kills off a character and then in the next book, he’s back again.”

During lockdown, I found myself again reading over The Book Of Evidence, and for the first time, I noticed the extent it seemed to be influenced by Camus’s The Outsider. Recently, I’ve found myself thinking that The Outsider is the most influential novel of the 20th century, but would Banville agree?

“No, I wouldn’t,” he says flatly. “I think Georges Simenon is a far greater writer than Camus. Camus and Sartre were too self conscious, too aware of themselves as cultural commentators and so on. Simenon just got on with it – he spent 10 days writing a book.

“Simenon’s son is a friend of mine, and he told me that when he finished a book, he would line him and his sister up in the hall. He’d shake the manuscript and he’d say, ‘What am I doing children?’ And they’d have to say, ‘You’re getting rid of the adjectives papa!’”

Advertisement

Having interviewed Banville a couple of times, it’s notable how often he cites the influence of Simenon, a hugely acclaimed Belgian crime writer. Given Banville’s reputation as a literary stylist – he even counts Don DeLillo as a fan – I wonder if Nabokov would also feature in his top tier of authors?

“Oh yeah,” he nods. “I think he was deeply insecure and covered it up with pretentiousness and self awareness. But he was an extraordinary man, his father was assassinated. Then he left Russia and lost everything he had. But he goes to America and makes himself into an international writer, an extraordinary achievement. I used to read Lolita regularly, but then I had daughters and it’s not quite the same book when you have a daughter.”

Of course, there is the ongoing debate about whether Lolita – and many other classics from the literary canon – would get published in today’s contentious cultural climate.

“It wouldn’t,” says Banville. “In this ridiculous age we’re living in.”

It’s hard to see that as anything other than a major cultural regression.

“I know, things are a dangerous at the moment. The universities are in bad trouble, and if the universities go, who’s going to produce the teachers to teach the young?”

As it happens, beside The Book Of Evidence on my shelf is one of my favourite novels, Cormac McCarthy’s ultra-violent western Blood Meridian, which boasts a blurb from Banville. What does he make of the book these days?

Advertisement

“Oh, it’s a tremendous novel,” he says. “The thing about Cormac is that, when you’re reading him, you’re completely mesmerised. And afterwards, you say, ‘Jesus Christ, that was way over the top!’ But he was a strange man, I was a friend of his. He used to come to Dublin now and then.

“He would never say where he was staying or who he was seeing – he’d just appear, you’d have a drink with him and then he’d be gone. I liked him a lot. Then I made the mistake of reviewing one of his books in The New York Review Of Books and I never heard from him again. Never review books by your friends! I think his best book is Child Of God, it’s very short. It’s a very sympathetic portrait of a serial killer. I mean, it’s horrifying, but I really recommend it.”

Cormac McCarthy. Credit: Beowulf Sheehan

Where would you meet McCarthy for a drink?

“I met him in the Shelbourne,” says Banville. “Also, my wife and I used to go to the southwest – we’d drive around for our summer trip. He lived in El Paso. I said to him, ‘Look Cormac, the house is too far south for us.’ He said, ‘Oh that’s fine, I’ll come up and meet you in Santa Fe.’ So we’d meet in the Fontana Hotel in Santa Fe, which does the best margaritas in the world, and we’d have lunch and drinks.

“I mean, he didn’t have the most highly developed sense of humour in the world. But he had a dry wit that was very effective. You didn’t get belly laughs with him, but I was fond of him.”

Advertisement

What would you talk about with him? Books? Politics?

“Oh no,” replies Banville. “I don’t know what we talked about. I mean, he was one of these far right people, you wouldn’t want to dabble in his politics.”

So you reckon he might have been a Trump guy?

“Oh, he would have been far more extreme than Trump,” says Banville. “He was kind of primitive, you know? One of his last projects was, he and a friend of his tried to to reintroduce wolves into New Mexico or somewhere. Only Cormac! I don’t know whether he succeeded or not. He had a very bleak view of the world. My god, look at the the world, why wouldn’t he?”

Well, if he was far right, maybe it was for the best that McCarthy – noted for his reclusiveness – didn’t give many interviews…

“Well, I really shouldn’t say far right,” says Banville. “He was a primitive person, he didn’t believe in civilisation. He thought human beings were savages and that we would always kill. So I shouldn’t say far right. Primitive is what he was.”

I mention that along with McCarthy, two of my other favourite writers are Donna Tartt and Thomas Harris. Although all three are very different authors, they are all southern and give very few interviews. I wonder if the southern literary tradition lends itself to that kind of self-mythologising.

Advertisement

“I met Donna years ago in Miami of all places,” says Banville. “We spent an evening together. Donna’s tiny, and here’s a coincidence, because she had just re-read Lolita and she realised she was the same proportions as Lolita. So, a tiny woman, but my god could she drink. She almost drank me under the table, which is saying a lot.

“But in terms of self-mythologising… I don’t know that it was a conscious programme on Donna’s part. I think she’s just genuinely a private person. Harris I don’t know anything about. Cormac really didn’t want to talk to anybody, he just didn’t. He wouldn’t even talk to me about anything except generalised things. I mean, I knew him for years and years, but I couldn’t say I knew him.”

McCarthy sounds like a character from one of his own novels.

“He was,” says Banville. “He was straight out of one of his novels. You see, one of his problems was, he’d been a big drinker, a bad alcoholic, and he wasn’t drinking. So there was always that.”

Another literary heavyweight – and another favourite author of mine – with whom Banville was friends was Martin Amis, who like McCarthy passed away last year. Did Banville remain friends with Amis until his death?

“I did,” he says. “He’d moved to America, so I didn’t see much of him. But we stayed in touch, I regarded him as a good friend. I miss him a lot. He was very gentle, he wasn’t at all like his public image. He was very sweet and kindly. I did a thing with him once, years ago on Newsnight. He was doing something and they invited me along, god knows why.

“Just before the programme started, they tried to get rid of me, and I said, ‘That’s fine.’ And Martin said, ‘If he doesn’t go on, I don’t go on.’ He was that kind of person, loyal, and great fun. We had a lot of laughs. So yeah, I miss him.”

Advertisement

The Drowned is out now.