- Opinion

- 07 Oct 21

As he releases his deeply personal autobiography, High Hopes: Making Music, Losing My Way, Learning To Live, Steve Garrigan opens up about his struggles with anxiety and depression, the ongoing stigma surrounding mental health, his love of Thin Lizzy, and how Gavin James almost joined Kodaline...

Publishing his memoirs at the age of just 33 had never been part of Steve Garrigan’s masterplan. But with only one quarter of his new book chronicling his arena-filling success as the lead singer of Kodaline, High Hopes isn’t your typical rockstar narrative. In fact, for the majority of his autobiography, the Swords-born artist, who generally keeps his personal life closely guarded, takes us on a remarkably honest journey from childhood to young adulthood – charting, all the while, his emerging mental health issues.

“It’s quite surreal,” Steve tells me, speaking with a refreshing openness that he’s often kept under wraps in past interviews. “It’s something that I genuinely never thought I’d do. If it wasn’t for Covid, I wouldn’t have done it – I would’ve been too busy.

“I was actually humming and hawing about doing it, at the start,” he adds. “One day I’d say, ‘Okay, I’ll do it.’ And then the next, I’d say, ‘I don’t want to do it’. Because I am quite private. But this book is just everything, for me – it’s wide open.”

Written with Neil Fetherstonhaugh, Steve hopes the book will be able to offer some insight into the struggles that have impacted his life – as well as the lives of countless people around the world.

“My main reasoning behind doing the book was to speak out about my own issues with anxiety and depression,” Steve states soberly. “I suppose a lot of people who would know me, or know of the band, might just be like, ‘Oh, he’s playing to thousands of people around the world, and selling records.’ But mental health issues can affect people from all walks of life. It doesn’t discriminate.

Advertisement

“I thought telling my story was the right thing to do – because it might encourage people out there,” he continues. “Particularly Irish men, who are just sucking it up, and just pushing through, saying, ‘Everything will be grand’. When the reality of it is, by being a little bit vulnerable, talking about it, and opening up about it, you’re being much stronger than you are when you’re just bottling it all up, and pretending to be strong. I bottled it up for years, and it didn’t do me any favours. It took me a long time to actually build up the courage to realise that I needed help, and there was nothing wrong with that.”

Of course, delving into some of the darkest periods of his life was never going to be an easy feat.

“I wouldn’t have been able to do the book if it wasn’t for Neil,” he nods. “He’s a lovely guy, and he helped me get it down on paper. It was quite a strange process, because we’d literally just be talking for hours and hours on end. Then we’d go through the story, changing it, and making sure it was right.

“Some of it was quite tough to go over, particularly the parts about anxiety and growing up – being so socially withdrawn, and being caught up in my head. Going over some of that stuff was quite triggering for me. So while I was doing the book, I went back to therapy as well, every week. When I was working on a certain chapter or something, I’d just talk through it with my therapist, just to make sure that it doesn’t trigger me again. So it was tough, but it was a great experience.”

In the run-up to the release, Steve now has to come to terms with sharing his story with the world.

“I still haven’t fully grasped that it’s going to be out there,” he admits. “Obviously I know, with anything that’s out there, there’s going to be critics and stuff. But this is a lot different from a song. A song is more like a poem – it’s more open to interpretation. This story isn’t really open to interpretation, because it’s my story. I know there will probably be people out there who won’t like it – but I suppose I’ll just ignore that. That’s just the way the world is.”

One aspect of the book that deserves particular attention is Steve’s eye-opening discussions of his panic attacks – something he first experienced when sitting in a Temple Bar restaurant, aged 20.

Advertisement

“I didn’t know what anxiety was until I had my first panic attack,” he tells me. “It was really horrifying for me – because it flipped my world upside down. I thought I was dying. Obviously it’s different for everybody, but it can feel like you’re having a heart attack. The strange thing about it is it all stems from stress and anxiety, and how you’re managing your emotions and thoughts. It’s crazy that it can be so physical – even though it’s in your head.

“There are ways to manage them,” he adds. “I very rarely have panic attacks now. Occasionally I’ll have anxiety attacks, but because of therapy, and coping mechanisms that I’ve learnt through therapy, I’ve got a handle on it. And I take it for what it is – because I know what it is. I kind of just push through it.”

As Steve points out, his lack of awareness about anxiety and panic attacks only compounded his problems at the time.

“Because of the time that I was living in, nobody spoke about it,” he remarks. “And I was genuinely so afraid of talking to anybody about it, because I thought that they would judge me, or think that I’m crazy, or avoid me – which kind of was the vibe back then. It wasn’t until a few years after I had my first panic attack that people started to open up about it, and anxiety became a common word.

“Even though the stigma has gotten a lot better over the years, it’s still – particularly with Irish men – pretty bad,” he continues. “I have friends who would never say that they’ve gone to a therapist. In other countries it’s a lot more normalised.”

That internalised shame is particularly notable when it comes to medication.

“I was on antidepressant medication for a while, and I think there’s still a bit of stigma surrounding that,” Steve agrees. “And there’s a lot of people on it – but they’re afraid to talk about it. They feel they might be judged because of it. I think that’s wrong. It works for some people, it doesn’t work for others – but there’s nothing wrong with it.”

Advertisement

Although opening up about his struggles has been far from easy, Steve acknowledges that he’s in a much better position than many other people in this country, in terms of his ability to access mental health services.

“I know I’m very lucky that I could afford a therapist,” he says. “Therapists are very expensive. I have a great GP too – and he was very considerate and helpful when it came to medication, when I was on that. A lot has to be done to improve the system, because there are a lot of people out there who don’t have the resources to get healthy. There’s obviously shortages and waiting lists as well.

“On the positive side, there are a lot of organisations online that are free to use, and there’s more now than there was years ago. It seems to be getting more and more common, particularly in Ireland.”

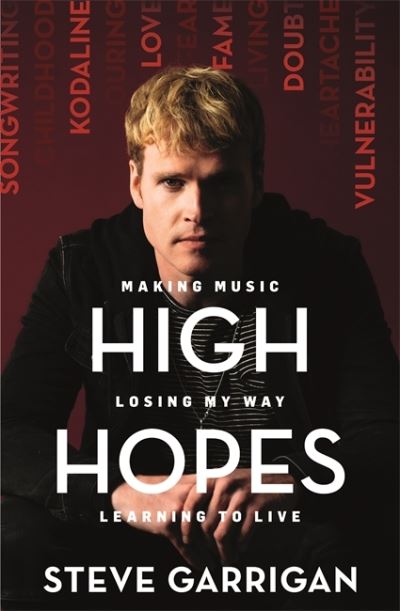

Steve Garrigan from band Kodaline. Copyrtight Miguel Ruiz.

Steve Garrigan from band Kodaline. Copyrtight Miguel Ruiz.Of course, his relationship with music has also been an important part of this journey – despite struggling with aspects of the industry during the early days of Kodaline.

“When we first came out, the thought of doing interviews scared me, a lot,” he laughs. “I didn’t realise that when you write songs and release music, you have to do interviews as well. That only occurred to me when the interviews started happening – and I was like, ‘Oh, dear...’. And having anxiety issues didn’t really help! But I could always lean on the guys.”

Advertisement

Despite the importance of music as an outlet, he stresses that it can’t always be used as a replacement for professional help.

“At the time when we first started out with Kodaline, I always said that music is not just music – it’s therapy,” he reflects. “And I meant that, because for me, that’s what I thought it was.

“I know there is music therapy, which you can study,” he acknowledges. “And any creativity is good for your mental health, by expressing yourself. But for me, music was escapism. It was great that it kept me afloat, but then there came a point where I realised that I genuinely needed to get professional help. I needed to go and speak to somebody.

“Today, I still love music,” he adds. “I’m so passionate about it and I love writing. I write songs every day. It’s great to lift your mood. But now, if I’m feeling off, or going through a tough time, I’ll talk to my therapist.”

Steve’s love of Irish music runs particularly deep – with references to some of his icons scattered throughout High Hopes.

“Myself and Mark [Prendergast] in the band were obsessed with Thin Lizzy growing up – Rory Gallagher as well, and Gary Moore,” he grins. “Occasionally I’ll still pick up a guitar and bash out a Thin Lizzy song – one of the riffs, something like ‘Jailbreak’ or ‘Emerald’. There’s too many! That’s the music I gravitated towards as a teenager. Myself and Mark bonded over that.

“Ireland’s great, isn’t it?!” he laughs. “There’s so many great musicians.”

Advertisement

Undoubtedly, Ireland has continued to produce a remarkable number of musical heavy-hitters in recent years, with homegrown artists making their mark on the world stage, across a multitude of genres. That includes, of course, Kodaline – who have sold out venues across the US, Asia and Europe, as well as clocking up over a billion Spotify streams. It also includes fellow Dubliner, Gavin James – who, pre-fame, almost got a job as Kodaline’s bass player, according to Steve’s new book.

“I remember seeing him playing in a bar on the quays years ago,” Steve recalls. “We had also played a gig when we were teenagers – he was in a band called The Problematic. I thought his voice was amazing. And he was very close [to joining Kodaline]. I had actually arranged to meet him in town, so I was getting on the Swords Express bus, outside Penneys, when he called me, and said, ‘I’m not going to be able to meet you.’ And the next day, we got our bass player, Jay, through a friend.

“It’s amazing,” he says, smiling at the memory. “We later took Gavin James on tour to America, to Europe, to the UK – and he’s gone on to have a great career himself. It would’ve been the wrong thing to do, for him to be a bass player, and singing backing vocals. He’s a singer-songwriter. He’s doing what he should be doing, because he’s very talented.”

As far as Steve sees it, music occupies a special place in Irish life – whether it's performed in an arena or in a pub – with roots that go deep.

“I grew up going to my Nana’s house, and her generation were big into sing-songs and gatherings, where everybody would do a party piece,” he says. “That still goes on around Ireland, particularly in some of the small pubs. People get together and they sing together, and play. It seems like it’s just embedded into our culture, and it has been for years. Everybody loves a sing-song – particularly in Ireland!”

In addition to working on High Hopes, Steve’s also been making new moves in the music world, writing for other artists for the first time. He’s also gearing up for Kodaline’s upcoming acoustic tour of Ireland, which they’re capping off with two nights at the newly christened 3Olympia Theatre in Dublin.

“We were going to do an album, but now we’re thinking we’re probably just going to take a little bit of a step back, and wait a while,” he reveals. “We’ve been releasing albums constantly – and touring relentlessly – since 2011. So we’re going to chill a little bit, but still be gigging and touring.”

Advertisement

For now, he’s feeling hopeful – having taken a major step forward in his own journey, with the publication of High Hopes.

“If I was to take a positive from Covid, it’s how it’s given me the time to look at doing things I never would’ve done before,” Steve reflects. “Including this book. I’m trying new things out, and I’m enjoying that. I’m excited.”

• High Hopes: Making Music, Losing My Way, Learning To Live is out now.

Read our full Mental Health Special in the current issue of Hot Press: