- Opinion

- 30 Nov 20

Luke O'Neill: "Trump was anti-science to his core. It was horrendous"

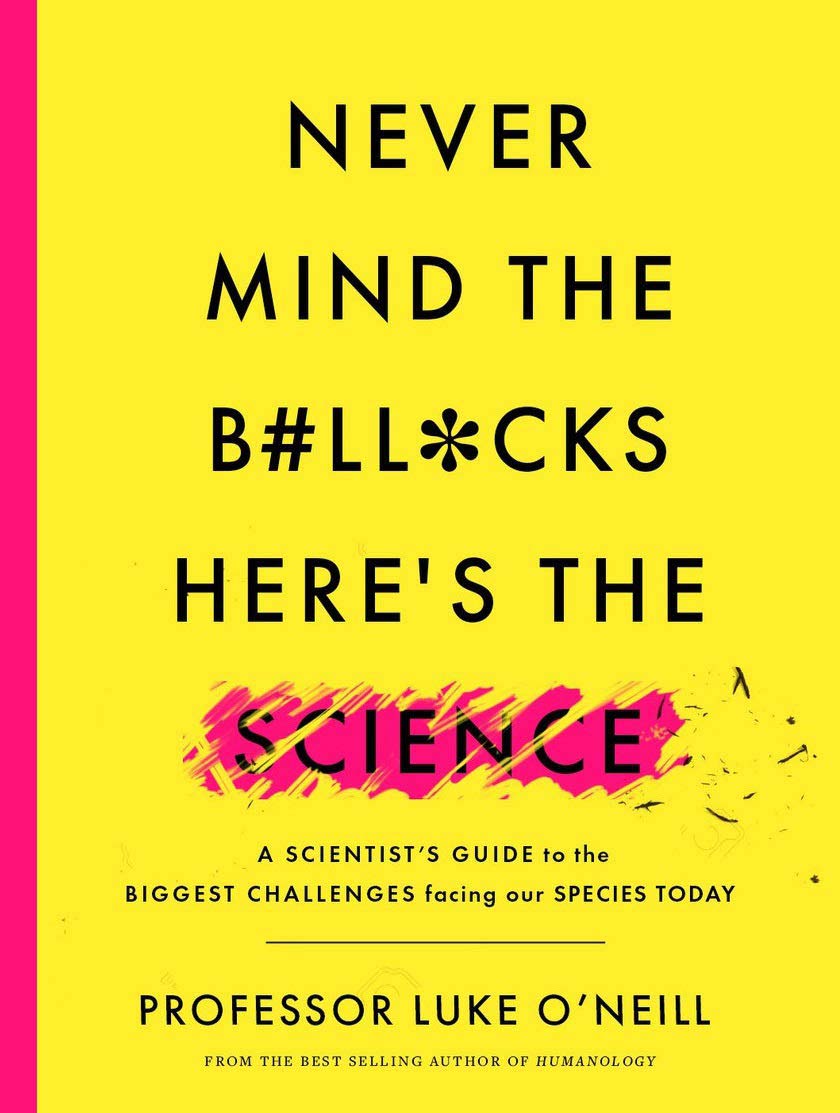

With the release of his new book, Never Mind The B#ll*cks, Here’s The Science, and his no-nonsense commentary on the ongoing global pandemic, Luke O’Neill continues to establish himself as a voice of reason and warm wit in the midst of prevailing madness. We paid a visit to the Trinity College Dublin professor’s lab, to discuss anti-maskers; Trump; vaccines; religion; his younger years as a “semi-professional” musician; and his epically-named current rock ’n’ roll band, made up of scientists and doctors, The Metabollix.

Luke O’Neill is sorting through the pile of today’s fan mail on his desk – ‘Thank You’ cards and letters from a grateful nation with a newfound preoccupation with viruses, masks, handwashing and vaccines. Inside one card is a cheque, from a fan looking for a copy of O’Neill’s sold-out book, Never Mind The B#ll*cks, Here’s The Science.

“He’s everywhere these days,” an attendant in the Trinity Biomedical Sciences Institute reception told me ahead of the interview. “A bit like Covid!”

Two years before he became the country's poster boy for scientific reasoning, I first saw O’Neill in very different circumstances – as he was playing to the raucous hoards at Trinity Ball. Although I was expecting to find a novelty act of middle-aged men bumbling around the stage, O’Neill’s band, The Metabollix – a group largely made up of scientists and doctors – proved to be the unexpected hit of the night. They also played Trinity Ball the following year, just before things began to go awry – a year that just so happened to be headlined by The Coronas, which is more than a little prescient...

Despite things having gone rather quiet on the gigging front for The Metabollix, 2020 has proved to be a momentous year for O’Neill. As a world-renowned immunologist, he has emerged as one of the leading voices during Ireland’s fight against Covid-19, while his acclaimed new book Never Mind the B#ll*cks, Here’s The Science sold out within a few weeks of its release in October, and was named Popular Non-Fiction Book of the Year at the An Post Irish Book Awards. If all that wasn’t keeping him busy enough, September also saw Swiss pharma giant Roche acquiring Inflazome, the biotech company O’Neill co-founded in 2016, for a staggering upfront payment of €380 million.

As O’Neill tells me: “It’s like three buses have come at once...”

We’re seeing the rise of the ‘approachable scientist’ now – is that how you see yourself?

No! Not at all. It’s a strange one – suddenly us scientists are in the media a lot. But I’m a communicator anyway – to students, for a start, as a teacher. I’ve also done a bit of science communication, with Pat Kenny and the various books, and I enjoyed it. But by God – in the past eight months or so, that’s gone up exponentially. And when you start getting recognised in the street, you know there’s something wrong (laughs). Us scientists, we like to work in labs, and do experiments, and do our jobs – not be celebrities! So it’s a bit of a disconnect.

The interest in science has exploded this year, for obvious reasons – what kind of impact do you think that will have in the long run?

There’s going to be good bits and bad bits. Take the vaccine for example – we’ve got to convince people to vaccinate, and there’s a reluctance for all sorts of reasons. But if you’re in the media a lot, saying it’s a good thing to do, then that will help. The downside might be if science doesn’t deliver – then they’re going to say, ‘But you told us…!’

Will science deliver?

I’m very confident that we will deliver on this, but there’s a risk as well. Particularly with this pandemic – you’ve got to be able to say, ‘Look, we don’t know everything. But, we think this might happen next, and here’s the evidence’. You can’t go around saying, ‘We’ve cracked it’ – because that’s just not true. So it’s really about trying to get the balance right between informing people and being realistic; and being as honest and truthful as you can. People are also now seeing how science really works. It can be challenging, and not definitive, and contradictory.

Have you supported NPHET’s recommendations, for the most part?

It’s very important to have that ‘We’re all in this together’ type of approach, because it is an emergency. They probably get things wrong occasionally, like everybody else would. They look at this through one lens – which is the public health lens. And that’s their job. We have to row in behind each other, but it’s still good to be critical, if we see something we don’t like the look of.

Like what?

I was quite critical of their early position on masks. They took a bit of time to tell people to wear masks, and I was like, ‘For Heaven’s sake…’ So we’ve got to be grown up about it as well. But by and large, they’ve done a good job. And they continue to do a good job.

‘We’re all in this together’ – do you believe that? It seems that the effects of lockdown aren’t spread equally, and they’ve been particularly hard on vulnerable groups.

That’s very true as well. What I mean by ‘We’re all in this together’, is that we know where we’re going, and that we have a leader. The Taoiseach is very important in that. It’s a tough job for politicians. If we lose faith in the bloody structures that are leading us, that’s a big disaster – because then it could be chaos. This does affect different sectors differently. And that means you’ve got to keep people on board as best as you can. If a certain part of our community is feeling hard done by, you’ve got to bring them back. The PUP is great. I would borrow as much money as I could, to limit the economic damage, for instance.

Professor Luke O'Neill at his lab in the Trinity College School of Biochemistry. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Professor Luke O'Neill at his lab in the Trinity College School of Biochemistry. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.Does the popularity of the anti-mask movement scare you?

It’s a bit unfortunate. It’s a free country – you can do whatever you like, and you can say whatever you like. And there’s always dissent. In science, there’s often sceptics and critics – and that allows science to move forward. If I go to a conference, there will be two or three equivalents to anti-maskers at the microphone, going ‘I don’t believe that – what you just said is wrong!’ And I like that! Because I’ll think about it, and I’ll change my science. As long as it’s reasonable, and there’s data to support what’s being said, I have no problem with it. Because the beauty of science: ‘Shut up – unless you show me data.’

Why are people anti-mask?

The anti-mask thing is a surprise to me – because the data behind mask-wearing is absolutely compelling. That wasn’t the case in January, by the way, because the data wasn’t there. But as soon as you get evidence, you have to say, ‘Hang on a minute now’. In fact, I would prefer calling them mask-deniers now, or vaccine-deniers. The equivalent is the Holocaust. We don’t call them anti-Holocaust, we call them Holocaust deniers! Because they’re denying the evidence. And that’s their right – anybody can deny evidence. Some people still think the world is flat! But if you’re a reasonable person, and you look at the evidence, you can say, ‘Right, I’m going to wear a mask – and protect other people by doing that’.

Its links with the far-right are also concerning...

It’s a bit of a surprise how that one emerged and got attached to various causes. I’m not a politician by any means, and I wouldn’t comment on the politics of it, but wearing a mask isn’t a political issue – it’s a public health issue. So how it got politicised is a complete mystery to us.

It wasn’t that long ago that Ireland was quite an anti-scientific society.

There’s always the fear of that. You can see it in what’s happening in America. I saw this thing this morning, where they’ve ranked countries based on responding to scientists in the pandemic. The US, tragically, is the worst for this. New Zealand is at the top – they listen to their scientists 100%. Now, you’ve got to get the balance right. If you only listen to scientists, that’s a danger, because you might make certain decisions that are harming certain sectors. That’s why the government has such a difficult job. They’ve got to balance all these things – the science, the medicine, the economics. And they’ll always piss someone off!

The title of your book, Never Mind The B#ll*cks, Here’s The Science, seems to be a response to the rise of misinformation and fake news. Do those trends worry you?

It’s always been there, for decades. I’m a big fan of John Lennon’s song ‘Gimme Some Truth’ from Imagine. It’s fantastic: “I’ve had enough of reading things… All I want is the truth.” So that book could be called Never Mind The B#ll*cks, Here’s The Truth. The power of science is to get to the truth with evidence and data. That’s what science is about.

What about the bollocks part?

The motto of the Royal Society, which is the world’s oldest scientific society, founded in 1660 by Newton and Boyle, an Irish guy, is: ‘Take nobody’s word’. That captures it for me. The reason the Royal Society was founded was to counter bollocks. They were saying, ‘Look, we’re not about a holy relic curing cancer – we’re about evidence’. That’s the essence of what science should be. We’re all a bit sick of fake news – what can we believe? Is it bollocks or is it not? So, as a scientist, I’m telling you, ‘Never mind the bollocks – here’s the science’.

The late 19th/ early 20th century saw people using pseudoscience to support racism. Is there a fear something like that could happen again, particularly in these divided times?

I hope not! In the book I talk about eugenics – they used science to justify torture. And there was no scientific basis to race at all. So the misuse of science is always a concern: we’ve got to keep a very close eye on that. When you’re an immunologist, you look for evidence that there’s a virus that’s driving an immune response, and you measure it in people. If you have a vaccine, you get evidence that the vaccine is working. We say, ‘Show me the goddamn data!’ We’re waiting now for this Pfizer vaccine – we haven’t the data yet. It’s a press release, so that makes you slightly uneasy! But I actually trust Pfizer, because I know them very well. Even so – it is all about showing the data.

How hopeful are you about the Pfizer vaccine, from a scale of 1 to 10?

I wouldn’t put a number on it! But from what we know so far, it’s looking very promising. The analogy I like to use is jumping fences in a race. And we’ve just jumped a huge fence. In fact, there’s just one more fence to go, and that’s safety – they haven’t told us how safe it is. But that’s the last fence – and if we jump that, the finish line is within sight. We’re tantalisingly close now. But I’ve been in this game long enough to know that you can fall at the last fence. You can even fall ten feet from the finish line. It’s unlikely, but there’s still a chance.

There has been a lot of optimism about it.

This is the first evidence that a vaccine might work. In other words, it’s like the Second World War, and we’ve just beaten the Germans in a very important battle – probably El Alamein, or one of those key moments. The war is a long way off ending, but now we know we can beat them. There’s still two or three more years to go, but we can now all begin to think, ‘This is a prospect now’. When Reeling In The Years is made in 20 years time, they’re going to go, ‘November 9 – Pfizer announced this’. Of course, if it all falls over, it won’t be in Reeling In The Years... But let’s hope it is!

Do you think Biden’s victory was another fence in that race?

Fantastic – I can’t tell you how happy I am with that. Trump was anti-science to his core. It was horrendous. I have a lot of friends in America who are scientists, and they were on their knees praying. About three weeks ago, the five top science medical journals wrote editorials, saying ‘Don’t vote for this guy’. That was unprecedented. Normally, scientists wouldn’t have a political comment – because we became scientists to avoid that! With Trump, it’s not only climate change, but Covid. It’s absolutely outrageous that 1.2 million people have died.

Why did that happen?

If you go back to around May, Trump and Fauci were saying, ‘We’re going to open up slowly’. And they had a roadmap. But that was ignored. So, we immediately went, ‘That’s going to be a nightmare for America’. And that’s what happened, which is horrible. So Biden has a tough job on his hands. The irony is that the US has got the best scientists in the world. Pfizer is an American company. Moderna is another big company. America leads the world in science. So why didn’t they listen to them?! So let’s hope we’re back on a good track with Joe – ‘sleepy’ and all as he is!

You’re a Bray man. What was it like growing up there in the ‘80s, when it was in its decline as a holiday resort town?

My father was English, and he came to Bray in the late ‘40s. He had a deckchair business – he hired deckchairs on Bray seafront. So we were always part of the tourist thing there. Bray boomed in the ‘50s and ‘60s – it was always crowded with tourists. This was before Mallorca came along. My dad used to reminisce about this – about the English and the Scottish people arriving over. Many people from Dublin had their honeymoons in Bray, which is amazing to think.

Then the ‘70s came along.

That’s when it started to go down. So when I was growing up, it was really like ‘Ghost Town’ by The Specials. We were all aware of that, but I loved growing up in Bray. I was in the Sea Scouts, so all day long we’d be out in boats. I actually took over the deckchair business. I ran it for three years when I was in college. It was the best job ever. On the weekend the Dubs would come out – so on a sunny Saturday, I would hire out 300 deckchairs!

Was your house religious growing up?

No, thankfully! My mother was quite Catholic, I suppose, but my dad was always very sceptical. My dad had fought in the Second World War. He was conscripted, he didn’t volunteer – his generation were all called up to fight. The war had a big effect on him, so he thought this religious thing was all nonsense. Occasionally he’d try to tell me to go to mass, but overall he was a bit of a sceptic. My mother insisted that I go to mass – like a good Irish mammy. Then when you’re a teenager you go, ‘Hang on a minute, this could be a crock of shit!’

Can religion and science be compatible?

No, they’re completely incompatible, but we’re very complicated as humans – we can hold two opposite things on our heads at the same time! Science is all about evidence. Some people of faith think there is evidence, but whenever the two mix, it’s always a mistake. The Shroud of Turin was a great example of that, when they tried to date it! It’s a bit like The Wizard of Oz – don’t pull the curtain back, because you don’t know what you’re going to find.

Not all scientists are atheists.

Interestingly, lots of my scientific friends are very devout, strange as it may seem. But they’re separate things, in a way. It’s unusual for scientists to have faith, obviously, but a lot of them do. My big motto is always: ‘Whatever gets you through the night’. If that’s for you, that’s fine – just don’t shove it down my throat! They have some similarities, of course – science is a kind of religion. It involves people in special garments doing mysterious things in a room, which is like a priest on the altar.

So what happens, or doesn’t happen, when people go to Lourdes?

On the positive side, it gives them a lift psychologically. That might help their immune system, who knows? It might boost an antitumor response in their body. I wouldn’t knock it at all. You can’t beat the power of positive thinking. Religions bring benefits, otherwise they wouldn’t have lasted so long. It’s a community thing and a social thing. And it gives people comfort.

Is there an afterlife?

Science was invented, in a way, to counter religion – in the days when they were burning witches. But then again, when you die, religion comes along to say, ‘It’s going to be okay’. That’s a comforting thing. As a scientist, I don’t believe in an afterlife. People might ask, ‘How can you cope with life, and people dying?’ And I say, ‘It’s all about the here and now!’ Of course, the downside of people going to those places like Lourdes is getting ripped off!

What do you find meaning in?

Science, of course! (laughs) That’s partly true. Science gives me great comfort, because it explains things wonderfully. With this pandemic, people say to me, ‘How are you so optimistic?’ It’s because I know science will win, because I know how science works. Science is the best thing we have, because it is about trying to reach a truthful discovery that could be useful, and that’s reproducible. So I do believe in science as a great thing.

What about your other passions?

You can’t beat music! That’s my other big passion. That keeps me going as well. Interestingly, out of all the faiths and philosophies, you’ll find more Buddhist scientists than any other calling. So if I was to be drawn to one thing, it would be Buddhism. It’s not really a religion at all, it’s just a way of living. It’s not about where we came from, or where we’re going, it’s about the here and now.

You studied in Trinity – what kind of student were you?

I was a bit of a messer, initially. I came in the first year and didn’t do very well. I enjoyed myself, and made some great friendships. My memories of all that are very fond. Towards the fourth year, I started to realise, “You better get a grip of this”. And then I really got into it, and knuckled down. I reformed my evil ways for those few months – I knew then, that I could go crazy afterwards.

How wild did the wild college days get?

I wouldn’t say I was putting myself in danger – but there was lots of craic. Not crack in that sense! Mind you, in those days, there weren’t that many drugs around. I remember in first year, they gave us a manual about the dangers of drugs. There was a list of LSD, cocaine and marijuana. But it wasn’t as commonplace as it is now. Ecstasy is freely available in Dublin now. Back in those days, a few pints, if you could afford them, was the main vice. We had our own homebrew in first year. We had no money, and a mate of mine made loads of homebrew – it was atrocious, but we still drank it. That was as good as it got.

Obviously exploring drugs and sexual experiences is a big part of college life – that’s now gone for students in 2020.

It’s a big shocker. I feel so sorry for them. For me, the most vulnerable groups in this whole pandemic are the 18 to 22-year-olds, and the older people. They’re the ones we need to worry about the most. The rest of us just get on with it. When you’re 18, 19 and 20, you’re like a salmon, trying to swim upstream. You want to make friends, identify with certain things, and get your own identity psychologically sorted. It’s a developmental process – like learning to speak or walk. And you might want to get a partner, or whatever else.

That’s almost impossible now.

They’re being denied that, because it’s a different world we’re in now. So we all worry about the long term consequences for that age group. The only advice I can give them is to try to keep their social activities going as best they can during this difficult time. It’s such an important part of their life.

What age were you when you had your musical awakening?

My dad was a great singer at parties. My mother sang too, so our house was always full of music. My dad had a great record collection. He loved ‘40s and ‘50s music – he was too old for rock ‘n’ roll, though he liked The Beatles.

Did you learn an instrument?

When I was seven, my grandmother died, and left us her piano. I had an ear for music, so I could pick out tunes on that. My dad said I was good at it, so I started doing lessons. But then, when I was 13, I realised I had to learn the guitar. I was a teenager, so I thought, ‘That’s a much better instrument!’ I had a couple of guitar lessons, and I just loved it. I was the guy who’d take out the guitar at the party, and annoy people. That was my job.

Did you play in bands back then?

I played in a few hit-and-miss ones in Ireland, and then I went over to do my PhD in London. I used to busk on the Underground a fair bit, to raise a bit of money. Then, when I was about 22, I met Tony Connelly – who’s now the Europe Editor for RTÉ. I met him through a friend of a friend, when he was just learning to be a journalist. He played guitar as well, so we used to jam at parties. We put a band together, and that was the start of the semi-professional years. We played loads of gigs. At one stage, we’d have three gigs on one weekend.

Were you any good?

We began to get quite good at it. But there was a key moment, around ‘89. We played a great gig one night, in a pub in Cambridge. There were seven of us in the band – you could probably describe us as a poor man’s Pogues. The Pogues were mega at the time in England, and every pub wanted an Irish band to play that kind of raucous punky-Irish music. After the gig, a guy asked me if we’d be interested in doing a little tour of Europe, to support this other band. Half the guys in our band were on the dole. I said to them, ‘Well, what do you think?’ They said, ‘Great!’ But I said no – because I had just made a scientific discovery at the time. I had to make a decision. Looking back, I was bloody stupid (laughs). I should’ve gone off for three months, it could’ve been great! Maybe I’d have given up science, and become an actual musician in the end.

Were the band raging?

I meet them occasionally, and they still kick me: ‘You bastard, you let us down there!’ But we laugh about it. Me and Tony actually ended up getting jobs in Dublin in the early ‘90s, and we put the band back together then. Singing ballads in an Irish pub didn’t go down quite as well as singing them in an English pub – but we still got a few gigs, and we played around various pubs in Dublin. One night, we were asked to support Scullion, in The Purty Kitchen in Dun Laoghaire. We loved Scullion – we even played some of their songs in our set. But in the bar afterwards, I overheard Philip King say to Sonny Condell, ‘Those guys – not great… Their setlist was a bit dated’. It was like Bob Dylan saying you were shit! Tony made a compilation tape for me after that, called Dated Music.

That’s not the end of the story, is it?

Four years ago, Philip King asked me to give a talk at Other Voices in Dingle. He found out about this story, and when I arrived in Dingle, Philip said, ‘Luke, I want to apologise. I’m a supporter of young bands, and I said the wrong thing that night, I’m very sorry’. He said, ‘To make it up to you, how about you and Tony play at the next Other Voices?’ So me, Tony and Philip played a bit of blues – and then we played a Scullion song, and he sang it.

So how did The Metabollix come about?

Many scientists are musicians – which a lot of people don’t expect. We put people in boxes – ‘Oh, he’s a scientist, he must be a nerd’. In 2017, there was a huge immunology conference in the RDS – with 800 people coming from all over the world. And the conference organiser asked if I could get a band to entertain the crowd.

A challenge you couldn’t resist!

I worked really hard on this. I was like Yul Brynner in The Magnificent Seven. My image for it was The Commitments. I recruited a couple of my mates, and mates of mates – and our drummer, who’s a neurologist, brought in a professional guitarist, Chris Cole. For that first gig we also had a neonatologist, a biochemist, a postdoc from my lab, and Anna Sheehan, who was only 18 at the time, but had a brilliant voice.

And you’re still going!

I thought it was just going to be a one off, but since then we’ve played loads of gigs – as well as Body & Soul and Electric Picnic. We’ve also played conferences in Fiji, Boston and Vienna – and we were due to go to Singapore, but we had to cancel it because of Covid. Our last gig was in Dar es-Salaam in Tanzania in March, for a cancer charity. I also did a podcast with Bressie recently, and we recorded three songs in his Camden Recording Studios. It was brilliant.

Is there a natural connection between music and science?

There’s something creative about science – you need to have good ideas and ways of doing things. When you’re doing an experiment, it’s kind of like playing a song – there’s different parts to it. And music can be very mathematical – like the chord sequences. There’s also something else about music which I love – which isn’t to do with science. Something mystical happens when a musician plays in front of an audience. It’s very hard to pin down, or describe that connection. It’s like that classic line from Louis Armstrong, when he was asked to define what jazz is: ‘If you’ve got to ask, you’ll never know!’

Of course, these are extremely tough times for musicians – can you envisage any way of gigs coming back?

I’ve got such sympathy for musicians now. Overnight, it was like a flip of a switch – and they had nothing. It’s like you’ve taken a scalpel out of a surgeon’s hand. And some musicians won’t come back from this. We’ve got to find some way to get back to gigs again. The immediate future might be testing – where you have to test negative before you go to a gig. But remember – in New Zealand, things are back to normal. There are gigs every weekend in Auckland, because they got rid of the virus. So it’s possible. We’ll never get to zero, but we might get the virus down to such a low level that we can go back to having crowds gather. Of all things to happen, who could have predicted that a virus would destroy the music industry? It seems outrageous.

You’ve had some good news this year too – with your company Inflazome getting snapped up for €380 million.

It’s like three buses have come at once – the Covid frenzy in the media, my company and my book. And this wasn’t designed! The book came out the week we sold the company – and that’s just pure coincidence. And people say there’s no God! (laughs) Selling the company was a huge thrill. The sale is obviously important for the investors – and I get a bit of money out of it too, it must be said – but it’s more about the patients, because Roche, the company who bought it, are the world’s biggest drug company, and they have all the money to do clinical trials.

What’s the first thing you do after a deal like that?

Well, you can’t go anywhere! There are no shops. So we couldn’t have a celebration, which was a bit of a tragedy. Most of the money goes to the investors, and a bit is left behind to be divvied up among the staff. The best part for me was that one of the investors, Fountain, which is a venture capital fund, has been invested in by the Irish Strategic Investment Fund. They get a cut of the profit as well, which goes back into the exchequer. So everyone wins – including the Irish taxpayer.

So no splashing out on a fancy sports car?

I don’t drive! I might hire a chauffeur though, you never know! Or a driverless car, but that might be a good bit down the line...

• Never Mind The B#ll*cks, Here’s The Science is out now.

Pick up your copy of the current issue of Hot Press in shops now, or order below:

RELATED

- Opinion

- 27 Jan 22

Spotify agrees to remove Neil Young's music following Joe Rogan dispute

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 17 Dec 21

8pm curfew for hospitality and live events: government announce new restrictions

- Lifestyle & Sports

- 17 Dec 21

NPHET recommendations: Close bars and restaurants at 5pm and cap attendance for events

RELATED

- Film And TV

- 15 Oct 21

Halloween Kills: Eenjoyable Outing For The Blockbuster Horror Franchise

- Opinion

- 15 Jul 21

Are we ready to go back to gigs? Have your opinion heard

- Opinion

- 13 Jul 21

The Barmaid's Tale Is a Warning That Must Be Heeded

- Opinion

- 15 Jun 21

The Canal: Last Refuge of the Young and Broke in Dublin

- Opinion

- 22 May 21