- Opinion

- 23 Nov 23

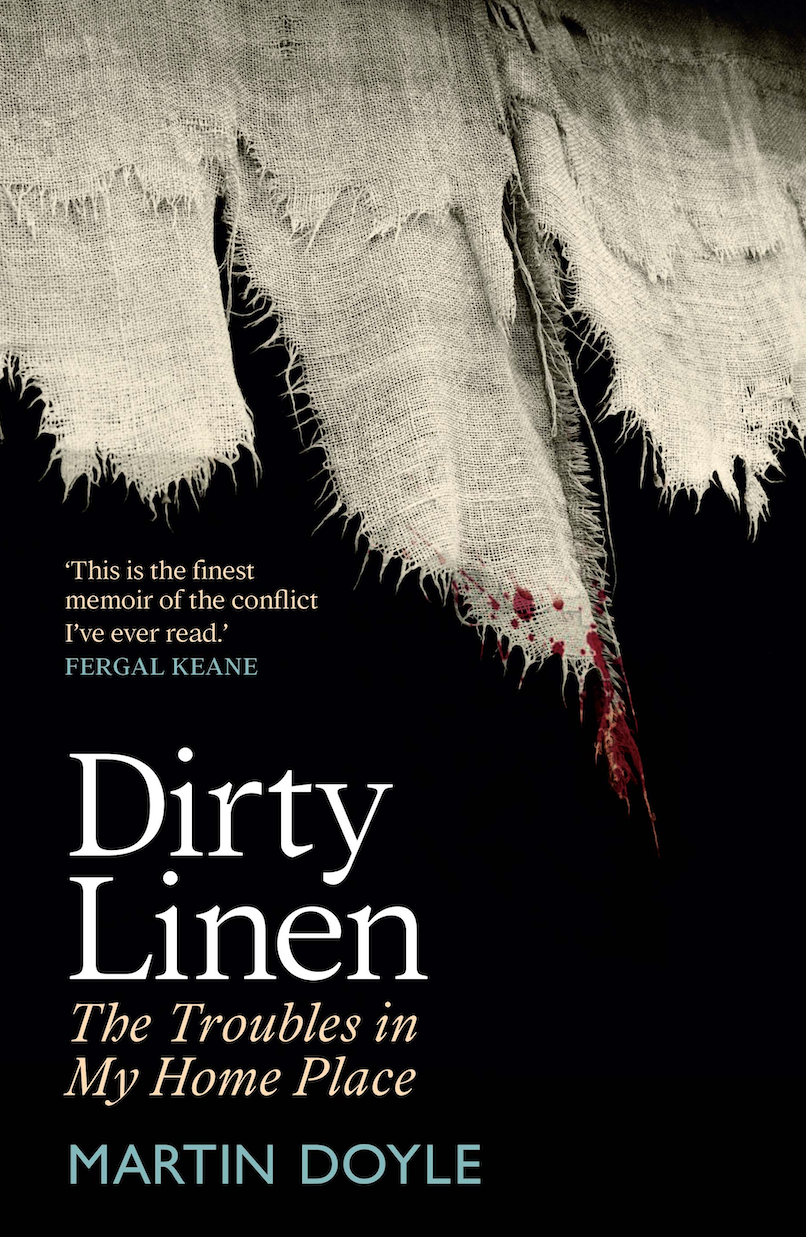

Martin Doyle on Dirty Linen: "Death is not something that happens in one day – it’s something that you live with for the rest of your life"

Martin Doyle’s new memoir Dirty Linen explores how victims, and their families, feel about the appalling cultural legacy of Ireland’s most traumatic period.

Earlier this year, we celebrated the 25th anniversary of the historic Good Friday Agreement, which brought an end to the widespread violence that had been endemic in the North, for almost thirty years. For some, however, the anniversary opened up old wounds, dredging up memories of murder and bringing trauma starkly to the fore again. That’s the way with a viciously, often thuggishly fought armed conflict. Brutal and bloody things are done that many might consider completely unforgivable.

Martin Doyle’s new memoir Dirty Linen explores this harrowingly dark territory. It casts a fresh light on what are euphemistically called ‘the Troubles’. In reality, that phrase masks a horrifically violent conflict which – as the alarming suicide rate in Northern Ireland confirms – sent shockwaves of trans-generational trauma cascading across the country that still reverberate today.

Dirty Linen is a victim-centred study of sectarian, political and State violence, examined through the microcosm of what happened in the small ‘parish’ of Tullylish. The book details the brutality experienced by those within the Murder Triangle, an area that was ravaged by paramilitary violence.

It’s a powerful literary declaration of collective remembrance – an account of the darkest passages of Northern Ireland’s history, as experienced by ordinary people. But why should we air Northern Ireland’s dirty history now?

“I am from a Catholic background,” Martin tells me. “I went to a state Grammar School, and therefore a predominantly Protestant school. I describe it not as mixed, or integrated, but diluted – diluted orange.

“The school admitted Catholics,” he adds, “but it really didn’t accommodate them. There was a lot of sectarian abuse towards the Catholic pupils, particularly when a local RUC or UDR man was killed. Catholics like myself, we kind of kept it to ourselves. We didn’t say anything to the teacher, we didn’t say anything to our parents – we just kind of sucked it up.”

Paula Jordan, a prominent special needs councillor in the North, attended the same Banbridge school as Martin. She was awarded an MBE for services to education in Northern Ireland last year.

“This is clearly someone that is a pillar of the community,” Martin reflects, “and yet her career as a special needs teacher was almost sabotaged at birth, by the sectarian actions of her Protestant headmaster at our school in Banbridge Academy.

“She had the grades to get into University to train as a special needs teacher, but even though people with lesser grades received offers, she didn’t.”

Jordan then asked a cousin of hers, who had connections to a Catholic teacher training college in Belfast, to have a look at her file. She discovered that her school reports had been doctored.

“What she found out was that her headmaster had described her as a ‘disruptive influence’, and as constantly ‘playing truant’, none of which was true. As a consequence, she actually had to repeat her A-levels, not to get better grades, but to get an honest reference from a Catholic school principal.

“I think it should be acknowledged that things like that went on. We’ve had a lot of books about the North, where the focus is on paramilitary violence, or politicians’ words. This time, I wanted to listen to what victims and their families had to say – the truth is in the detail. I think that dirty linen really is worth airing in public.”

POWERFUL EMOTIONS

There is a sense of decency and humanity at the core of Dirty Linen, with Martin deftly recounting the lived experiences of victims and creating poignantly evocative portraits of the dead.

“Barney O’Dowd was my milkman,” he recalls. “He would stand on my doorstep six days a week delivering milk. On a Saturday, he used to have a satchel around his shoulder full of coins, and he would let you put your hand in and grab a fistful of coins, like it was a treasure chest.

“On the 4th of January 1976 on a Sunday evening, he and his family were having an end of Christmas Holidays gathering, when loyalist gunmen burst in, shot dead two of Barney’s sons, Barry and Declan, and his brother Joe. Barney himself was seriously injured. After that, the whole family decided to move south – Kathleen, Barney’s wife was terrified that the remaining brothers would also be targeted.”

The genesis of the book was in a piece that Martin wrote for the Irish Times, where he is Books Editor. Following on from that article, Martin was given the opportunity to interview Barney – now in his nineties.

“You can imagine how powerful that is, to meet someone you haven’t seen in 45 years, that you last saw just before such a terrible atrocity,” he says. “I was interested in talking to ordinary people about what they had suffered, how they had coped and how they remembered. Eamon Cairns lost two of his sons ages 18 and 22, they were shot dead in the family home an hour after their sister Roisin’s 11th birthday party.

“If you can imagine the enormity of that, and what it must be like for Roisin to celebrate her birthday every year after that. The family still live in the same house. The thing that shocked me, that summarised the terror and the trauma of the Troubles, and how it lasts down decades, was that when Kathleen died in 1999, they decided as a family that they wanted to rebury their two brothers beside their mother in County Meath.”

It’s a harrowing story.

“The detail that really got me,” Doyle continues, “was that they decided to do it themselves. They personally exhumed their brothers’ bodies 24 years later, to bury them beside their mother – that to me, was like something from a Greek Tragedy. I also interviewed a man who was a victim of the Derry Darts Club Massacre. In his living room, he showed me an alcove in which he had cut up the local paper, the Lurgan Mail, which covered the murders of his friends. He cut it up in four sort of small frames on his wall, so that he would never forget.

“It’s not just about how they died, it’s about giving people an opportunity to talk about their loved ones. What sort of a person they were – their passions, their interests, and also about the impact of that violence, not just at the time but down through the years.”

Martin lost his wife to cancer ten years ago, a traumatic experience of grief that shaped his approach towards victims of the Troubles.

“Having experienced loss myself, I think I was very sensitive to the powerful emotions that I was tapping into,” he says. “Most people were happy to tell their story – one or two got back in touch and were almost apologetic to say that they couldn’t talk about it. It was just too painful. That was absolutely fine, there was no way I was asking twice. I never turned up on anyone’s doorstep, I always approached it very sensitively.

“Richard Beatty, his father was one of three Protestants who were killed in an INLA bombing at a pub in Gilford – he said he had never talked about it with anyone, not even his siblings. He was happy to talk, but there were times when it was painful for him. Sometimes I would take over the conversation and speak about my own experiences of loss. In the same way, I have tried in the book to share my own vulnerability.”

It was a difficult process, as Doyle acknowledges.

“I have an understanding that maybe I didn’t have before,” he says, “that death is not something that happens in one day – it’s something that you live with for the rest of your life.”

ACHIEVED VERY LITTLE

In the conclusion of Dirty Linen, Martin Doyle quotes a piece by poet Damien Gorman, who wrote a memoir detailing the sexual abuse his brother suffered at the hands of his school’s headmaster in Newry.

“Damien wrote a piece for me reflecting on what it’s like to write a story on someone’s behalf like that,” says Doyle. “He said, ‘The first rule, if you like, is don’t be a tube’. In other words, don’t be selfish or careless, don’t treat other people’s lives like material. Because what do you do with material – you tear it up, you stitch it up. I wasn’t pursuing the best story possible; I was trying to tell these vulnerable people’s stories in a way that they were happy with.

“You don’t want to trigger anything. These bereaved people, one of the most important things to them, is they want their children to be remembered. Newspaper articles and clippings yellow with time, but a book hopefully has a bit more permanence.”

As violence escalated and the North descended into political turmoil, many emigrated to England, or settled elsewhere in Ireland in an effort to escape the bloodshed – my father included.

“We did absolutely contemplate it,” says Doyle. “I knew there was a lot wrong with where I lived. As a child you are sort of conservative, and you stick with the status quo, rather than face the upheaval of moving somewhere where you have to start all over again. Every story is different. The O’Dowds moved to the south. And the Kearns’, just a few hundred yards down the road 20-odd years later, when similar violence came to their door.

“They still live there. I sat in their kitchen, where the gunmen had entered their house to kill their kids. It’s probably very important to them to live on in the only house where their children had ever lived. Their spirit and history is very much there.”

The general sentiment in the South during that era, particularly in Dublin, seemed to be one of sheer incomprehension – how could people we knew, lived just down the road from, be engaged in brutal sectarian murders and guerrilla warfare? It was different in the North.

“I think you did become used to it, without embracing it, but you sort of resign to it,” says Doyle. “There used to be Christmas ceasefires, and this sort of annoyed me – this idea that you could turn the violence on and off like a tap. Peace should be for life, not just for Christmas. I was kind of angry, but to a degree what can you do – aside from voting for parties that were progressive? Northern Ireland had to change.

“The Civil Rights Movement was a peaceful protest movement, an activist movement, that brought Catholics and Protestants together – to me, that was a movement I would have wanted to be a part of. The violence of republicanism, what did it achieve? Where are we today after 30 years of violence, that we couldn’t have been without all of that?

“There’s a poll saying something like 69 or 70 percent of Catholics agreed with Michelle O’ Neill that the IRA’s Campaign of Violence was justified. I hope by reading ordinary people’s experiences, they will realise the violence wasn’t justified. It was appalling and terrible.”

The leader of Sinn Féin in Northern Ireland, O’Neill had suggested that there was “no alternative” to the IRA’s armed campaign.

“If you want a united Ireland, how are you going to achieve that?” says Doyle. “There are social and financial issues, which are as relevant to people as ideological or identity issues. Given the amount of trauma inflicted upon the Protestant community in the North by republican violence, I think nothing could be more healing than a bit of honesty, a bit of humility and humanity.

“To acknowledge that, ‘You know what, those 30 years of violence, they achieved very little’. You can’t achieve a united Ireland over the dead bodies of your Protestant neighbours, even if they’re wearing the uniform of the Ulster Defence Regiment or the RUC or the PSNI. That murder has a ripple effect across the entire local Protestant community. It’s very understandable that they conceive of an attack on one as an attack on all. The wounds might fade, but the memories don’t – I think acknowledgment on all sides can only be healing.”

PROTESTANT VICTIMS

If you believe the polls and the pundits, a Sinn Fein-led government seems increasingly likely in the South. Is there an alternative?

“In the North of Ireland there’s options. There’s the SDLP, which supports a United Ireland and opposes the use of violence. There’s the Alliance Party, who are currently neutral to the idea of a United Ireland. There’s small left-wing parties like PBP – so there are options. If you want to vote for Sinn Féin, vote for Sinn Féin, but be conscious of the fact that there is a chill factor for the people you are trying to persuade.”

After the October 7th murderous armed incursion by Hamas into Southern Israel, increasing attention is being paid to Sinn Féin’s previous links to Hamas. Are there parallels with Northern Ireland?

“I think all violent death is terrible, and it’s obvious that violence can be meted out by the State just as much as it can be by paramilitaries,” says Doyle. “But I would be loath to get into a denunciation of one side of a conflict. You can’t map the history of Northern Ireland onto the history of Palestine. There are other issues at stake. In my book I put side-by-side Catholic and Protestant victims, so when I look at Israel and Palestine, I see Muslim and Jewish victims side-by-side as well.”

For those of us for whom the Troubles is not in living memory, the conflict in Northern Ireland can often seem abstract – a distant spectre of something sinister, reduced to a furrow in a loved one’s brow, or grainy film footage from the ‘70s.

“I think if you’re of a certain generation, the Troubles are history, just as the War of Independence is history,” says Doyle. “Maybe the two can become conflated, when they are radically different.

“Maybe this book is a way of communicating just how bad life was during the Troubles, to a new generation – or even to remind older generations that have forgotten the details, just how grim it was.”

• Dirty Linen: The Troubles In My Home Place by Martin Doyle is available now.